|

|

|

|

The Quagmire of Higher Education:

looks at where higher education has come in India and where it is going.

Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

Books: |

|

|

Serious Men

by Manu Joseph

Read Read |

|

|

Khaki and Ethnic Violence in India - Armed forces, Police and Paramilitary during Communal Riots

by Omar Khalidi Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

Films: |

|

|

Raajneeti

(Dir: Prakash Jha)

Read Read |

|

|

Peepli Live

(Dir: Anusha Rizvi and Mahmood Farooqui)  Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Home > Contents > Essay: Lalit Joshi |

|

|

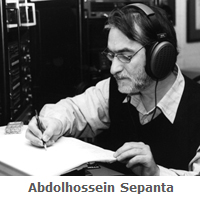

A Celluloid Journey to India: Abdolhossein Sepanta and the Early Iranian Talkies

Lalit Joshi

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This essay deals with the early history of the Iranian talkies and how one of its founders ? Abdolhossein Sepanta, pioneered the first Indo-Iranian  project in filmmaking in 1931. I briefly examine Sepanta?s transition from the academic world to the film industry. Sepanta desired to establish a full-fledged film industry in Iran and India became the testing ground of his cinematic skills. When Himanshu Rai, the founder of the Bombay Talkies (1934-54), hired the German cinematographer Frantz Osten, the films and the audiences in mind he had, were primarily based in India. But Sepanta?s projects represent the only instance in the history of Indian cinema when films for a foreign audience were shot and processed by an Indian film company. However, as I shall demonstrate in the concluding section of this essay, filmmaking for Sepanta ended abruptly as, an unfinished project of cultural nationalism. project in filmmaking in 1931. I briefly examine Sepanta?s transition from the academic world to the film industry. Sepanta desired to establish a full-fledged film industry in Iran and India became the testing ground of his cinematic skills. When Himanshu Rai, the founder of the Bombay Talkies (1934-54), hired the German cinematographer Frantz Osten, the films and the audiences in mind he had, were primarily based in India. But Sepanta?s projects represent the only instance in the history of Indian cinema when films for a foreign audience were shot and processed by an Indian film company. However, as I shall demonstrate in the concluding section of this essay, filmmaking for Sepanta ended abruptly as, an unfinished project of cultural nationalism.

National cinemas across the world have generally displayed a tendency to draw upon the diverse traditions of their performing and visual arts. Iranian cinema is no exception. Perhaps an early example of Iran's visual history is the appearance of bas-reliefs in Persepolis around 500 B.C., an art which reached its creative peak during the reign of the Sassanian kings. This tradition continued in the form of miniature paintings during the early and later medieval periods. According to Shahin Parami, a "deliberate lack of perspective enabled the artist to have different plots and sub-plots within the same space of the picture.[1] Moreover, Iranians were the only cultural community in the region, to have perfected the art of integrating storytelling with painting (pardeh-khani). In pardeh-khani, as the oral narrative progressed, the Pardeh-khan or the narrator, unveiled a series of paintings pertinent to a particular stage of the narrative. A similar audiovisual mode was the Nagali, in which a Nagal or the storyteller, would enact scenes from a story and interlace it with songs and dances. Nagal performances were generally organized in a ghave-khana or a coffee-house. Other art forms that embellished the visual culture of Iran included the Khaymeshab-bazi (puppetry), Saye-bazi (shadow plays), Rouhhozi (comical plays) and Tazieh (passion plays), depicting the martyrdom of the Shia leader Imam Hossein in the century.[2]

The advent of cinema in Iran marked a difficult transition not only into a new performative mode, but also to the creation of new spaces for cultural consumption. Furthermore, the adoption of the new mode of storytelling meant selectively drawing upon Hollywood films and diverse styles of European cinema, while at the same time appropriating elements from traditional performing arts and finally relocating them into new diegetic spaces. Cinema also created new sodalities of viewers who interrogated prevailing public discourses about the nation, politics, morality and everyday life and their representations in art. [3]

As in the case of other national cinemas, early attempts at filmmaking, exhibition and viewing in Iran were confined to the aristocracy and the upper classes. Many of the pioneers of Iranian cinema were foreign-returned technicians, belonging to the ruling elite.[4] Also, in many upper class homes, weddings, childbirths, circumcisions and other family events were filmed or films were screened during such occasions. Early film exhibitions were confined to European imports. However, around the second decade of the twentieth century, small investments began to trickle into indigenous film production. Rare footages of this period reveal a mélange of "news, events, actualities and spectacles involving royalty usually filmed in long shot.[5] Perhaps the first among these was the short film documenting the visit of the Shah of Iran to Belgium. The event was captured by Ebrahim Khan Akkasbashi, the official photographer at the royal court.[6] Later, Akkasbashi also filmed national festivals such as Moharram as well as scenes from the royal zoo in Tehran.

In the absence of proper exhibiting space, a select audience sat on carpeted floors to watch films, somewhat in the same way as they did during the Ta'zieh shows. Because of the restricted nature of its exhibition and because of the prejudices held against it, early Iranian cinema was far from being a popular art form. Films were thought to be morally corrupting; the clergy counseled men to restrain women from visiting theatres. Such biases were not uncommon in other cultures.[7] In neighboring India, the nationalist leadership, with notable exceptions, preferred to distance itself from the irresistible charms of the silver screen. However, cinema's entry into the public domain was only a matter of time. Business communities were quick to seize the initiative. The lead was taken by Mirza Ebrahim Khan Sahaf Bashi in 1904, who arranged a public screening of a short film inside the premises of his antique shop in Tehran. The response was so overwhelming that he was enthused to build a movie theatre of modest dimensions in the Cheragh Gaz avenue.[8] Sahaf Bashi's foray into the world of cinema could have been an enduring enterprise had it not been for his avowedly public support for constitutional politics in Iran. His fulminations against the monarchical form of government in Iran as well as the role of the clergy, earned him two powerful enemies. Pitted against two foremost forces, Sahaf Bashi soon realized that he was fighting a losing battle. His enemies ensured that he was arrested and his theatre vandalized and shut down permanently. Soon after this incident, Russi Khan - Sahaf Bashi's contemporary and an entrepreneur of Russian descent - was granted permission to open another theatre in Tehran(1906). Unlike Sahaf Bashi, Russi Khan had powerful patrons at the royal court. Besides, the Russian army which was then stationed close to Tehran, assured him complete protection and support. Khan's theatre enjoyed undiminished popularity until 1909, which year a constitutional government dislodged the monarchy and his theatre sealed forever. [9]

When monarchy was restored again in 1912, the former patrons of cinema began to work towards its revival. With adequate support from the royal court pouring in, Ebrahim Khan Sahnafbashi-i-Tehrani built the first commercial movie theatre of Iran, while Khan-baba Khan Mo'tazeidi - the royal photographer - announced the opening of a string of exhibition houses in the country. Another young entrepreneur - Ali Vakili - decided to hold exclusive screening for women inside a Zoroastrian school. An advertisement appearing in a local newspaper in 1926 gives us a foretaste of Vakili's marketing skills:

The famous series by Ruth Roland, the renowned world artist will be presented at the Zoroastrian school from May 10, 1928. Watching the incredible acrobatics of this international prodigy is a must for all respectable ladies. Get two tickets for the price of one. [10]

In another announcement, the owner of the Grand Cinema in Tehran went as far as stating that the management would filter unclean women as well as immoral youth from its audience so that only respectable men and women could watch films separately:

As a service to the public, the Grand Cinema Management has demarcated parts of its hall for the ladies and from tonight, parts one and two of the series "The Copper Ball", will be presented together. Thus all citizens, including the ladies may enjoy the entire series. Measures will be taken with the cooperation of the honorable police officers to bar unchaste women and dissolute youth with no principle. [11]

In yet another innovative experiment, it was decided to hold screenings between two o' clock in the afternoon and sunset as this coincided with the time earmarked for Ta'zieh shows. Indeed, cinema cast such a magical spell on the audience that the proprietors of the Ta'zieh shows were steadily driven out of business. [12]

Two more names in Iran's fledgling film industry deserve mention. The first among these is Ovannes Ohanian and his contemporary Ebrahim Moradi. Of Armenian-Iranian descent, Ohanian had studied cinema at the Cinema academy in Moscow. When he returned to Iran in 1925, albeit he wanted to lay the foundations of a full-fledged film industry, he struggled to remain content with a film school in Tehran. In 1929, Ohanian and with help from some of his graduate students and financial assistance from a theater owner, directed his first film - Abi va Rab, which was a remake of Danish comedy serials already popular among Iranian audience. [13] Ohanian also directed Haji Agha Aktor-i-cinema (1933) - his second and last film. To his dismay, Haji turned out to be a commercial failure. Not much is known about his career thereafter except that he sought refuge in other pursuits for some time before sailing to India, where he remained until 1947. Like Ohanian, Moradi also learnt the craft of filmmaking in Russia, where he lived as a political exile in the early 1920s. Moradi returned to Iran in 1929, established his own studio (Jahan Namaan) and shot Entegham-e-Baradar (A Brother's Revenge) in 1930. The film could not be completed as Moradi overshot his budget. He continued to make other films, the last being Bolhavas (The Lustful Man) in 1934. The film was received well at the box-office but not well enough to sustain his enterprise. [14]

Thus by the mid 30s, the Iranian film industry was in a state of disarray. Filmmakers grappled with inadequate finances, low end technology, poor production and exhibition facilities and above all unflinching opposition from the clergy. It would however be misleading to suggest that Abdolhossein Sepanta embarked upon a career in filmmaking in India precisely because of these reasons. In fact, Sepanta's voyage into the world of films can be termed serendipitous; perhaps when he arrived in Bombay in 1927, all he must have had in his mind was to become a person of great erudition.

Abdolhossein Sepanta (1907-69) was born in Tehran. He went to St. Louis and Zorosatrian colleges, where he developed a profound interest in the early pre-Islamic history and culture of Iran. Sepanta's intellectual pursuits brought him to India in 1927. In Bombay he met Bahram Gour Anklesaria - a scholar of ancient Iranian languages and who was to become Sepanta's mentor later. He also met Dinshah Irani, Director of the Iranian and Zoroastrian society. A direct descendant of a refugee family who had fled Iran in the 1790s, Irani, a lawyer by profession, was a distinguished member of the Iranian diaspora in India. He had founded the Iranian Zoroastrian Anjuman as early as 1918 and the Iranian League in 1922. Sepanta's interactions with the Parsi families in Bombay brought him in touch with Ardeshir Irani, an event which was to change the lives of the two great men completely.

Born in Pune, Ardeshir Irani (1886-1969), studied at the J.J. School of Arts in Bombay. He initially joined his businessman father who dealt with phonograph equipment but quit it to carve out an independent career in film exhibition.  For this purpose he entered into partnership with another Parsi entrepreneur ? Abdullah Esoofally. The two acquired the Alexander and Majestic Theatres of Bombay in 1914. Six years later, Irani launched Star Films in partnership with Bhogilal K.M.Dave. Their first production ?Veer Abhimanyu ? was released in 1922. In 1926 he realigned his business to form the Imperial Film Company. The result was a series of films such as Anarkali (1928), The lives of a Mughal Prince (1928), Indira B.A. (1929), Alamara (1931), Bambai Ki Billi (1937) and Kisan Kanya (1937). Irani was a pioneer in two significant ways. He is credited not only for making the first talkie in India (Alamara) but also for producing the first color film (Kisan Kanya) in the country. So animated was Irani at the prospect of being associated with the first Iranian talkie that he agreed to finance and co-direct the film as well. For this purpose he entered into partnership with another Parsi entrepreneur ? Abdullah Esoofally. The two acquired the Alexander and Majestic Theatres of Bombay in 1914. Six years later, Irani launched Star Films in partnership with Bhogilal K.M.Dave. Their first production ?Veer Abhimanyu ? was released in 1922. In 1926 he realigned his business to form the Imperial Film Company. The result was a series of films such as Anarkali (1928), The lives of a Mughal Prince (1928), Indira B.A. (1929), Alamara (1931), Bambai Ki Billi (1937) and Kisan Kanya (1937). Irani was a pioneer in two significant ways. He is credited not only for making the first talkie in India (Alamara) but also for producing the first color film (Kisan Kanya) in the country. So animated was Irani at the prospect of being associated with the first Iranian talkie that he agreed to finance and co-direct the film as well.

The first Irani talkie Dukhtar-i-Lor or the Lor Girl was produced jointly Sepanta and Irani under the banner of the Imperial Film Company. The film had a prominent Iranian(Abdolhossein Sepanta, Ruhangiz Sami-Nehzad, Hadi Shirazi) and a small Indian (Sohrab Puri and other junior artists) cast. Sepanta wrote the entire script and played the lead role as well. The Lor Girl took seven months to be completed. It created quite a sensation in the Iranian press as a Muslim girl had been cast in a film for the first time in the history of Iranian cinema. The film opened at Mayak and Sepah in Tehran in 1933 and became an instant box-office success. It ran successfully for two years, a feat that could not be replicated by any other film for a long time altogether.

The Lor Girl is a political film not only because it is set in the turbulent 20s but also because it also marks for the first time, the appearance of a woman in an Iranian film. Ziba Mir Hosseni has recently argued that the clergy was unequivocal in its rejection of cinema because for the first time an art form had made women visible (haram) in society.[15] The managers of Ta'zieh shows for example, never showed women on stage, women's roles being always played by men. It has also been suggested that poets were careful in overtly representing women as 'beloved' in Persian verse; rather, they chose to work within ambiguities (iham).[16] Iranian cinema was not alone in preventing such transgressions. Japanese cinema, inspired by local theatrical traditions such as the kabuki and shipna, deployed the onnagata (male actor in female role) throughout the 1920s and the early 30s. In the case of India, Raja Harishchandra, one of the first Indian feature films and directed by Phalke, had Salunke- a teahouse waiter- playing the female lead.

The story of Lor Girl revolves around a tribal village girl-Golnar (Ruhangiz), who earned her livelihood by singing and dancing in teahouses and Jafar(Sepanta), a government agent. The two fall in love and escape to India. They return to Iran after the restoration of political stability. The film is emblematic of the fate of ordinary lives during a period of political turbulence. What Sepanta might have had in mind when he was doing the script could have been the political situation in the Lorestan-Khuzistan region, where the government had mounted a limited military offensive against the recalcitrant tribal population. Finally, the film narrative suffered from the problems of continuity and editing. The audience however, fell in love with the beautiful and innocent Golnar who is shown wearing a partial hejab in the film.[17]

Except for its Parsi background, there is no explanation for what might have attracted Sepanta to the Imperial Film Company. Around the late 20s, production houses and studios had started mushrooming in Bombay, Pune and Kolhapur. The Indian Cinematograph Yearbook of 1938 lists 34 production companies in Bombay, 6 in Kolhapur and 4 in Pune.[18] Besides, Irani had shown little evidence of making sound films. In fact when Wilfred Deming - an American engineer representing the Tanar Recording Company in India - visited the Imperial Studios, he expressed consternation at the prevailing conditions:

Film was successfully exposed in light that would result in blank film at home, stages consisted of flimsy uprights supporting a glass roof or covering. The French Debrie camera with a few Bell and Howell and German makes completed the rest of photographic equipment. Throughout, the blindest groping for fundamental facts was evident. The laboratory processing methods, with sound in view.were most distressing and obviously the greatest problem.[19]

Poor sound and lip synchronization in films produced by the Imperial Studios, was also reported in the Bombay Chronicle and the Times of India.[20] Irani's testimony however, reveals another side of the story. He accused the Tanar Company of selling him "junk" equipment based on the single system process that did not allow sound to be edited later as it was directly transferred to the negative plate.[21] Such contestations notwithstanding, Sepanta pitched for the Imperial Studios where the Lor Girl was finally born.

Buoyed by the success of its maiden Iranian venture, the Imperial Film Company offered Sepanta production control over other films. Sepanta subsequently directed four more films for the company, all shot in Indian locations. The first among these was Ferdousi (1933), based on the life of the famous sixteenth century Persian poet. This was followed by Shireen va Farhad (1934), an adaptation of the classical Persian romance that became popular during the reign of the Sassanian king Khusrau I. In 1935, Sepanta directed Chashmaye Siah depicting the impact of Nadir Shah's invasion on the lives of two young lovers. It is noteworthy that Sepanta cast a new girl in each film.[22] This was a daunting task indeed. In the 20s and 30s, even Indian filmmakers were compelled to hire European or Anglo-Indian women, cinema being looked down upon as a disreputable profession by the society at large. It has been suggested that the songs in Sepanta's films were not favorably received by the audience.[23] From the point of view of the Iranian state, this was certainly not problematic. In fact the idea of making films purely for entertainment had never found favor with the state. Nonetheless, this should not lead us to the conclusion that because entertainment was a matter of low priority, Sepanta's films included subtle political subtexts. Stating his position on the Lor Girl several years after its release Sepanta observed, "As it was the first Iranian sound film to be presented abroad, I felt it should present a bright picture of Iran.I have to admit that the film was a great boost for the nationalistic pride of expatriate Iranians.[24]

In 1935 Sepanta quit Bombay to seek new opportunities in Calcutta. There he came in contact with Debaki Bose, the founder of the New Theatres and Abid Basravi, a merchant of Iranian descent. Basravi demonstrated extraordinary interest in Sepanta's plans to direct Laila-va-Majnun under the banner of the East Indian Company. Sepanta cast Basravi, his two sons and select members of Indian Iranian families in this film. The film was completed in 1936, with the Basravi family providing necessary assistance in the various stages of the scripting, shooting and editing of the film. A triumphant Sepanta set sail for Iran hoping to screen it for Iranian audiences. But how hope quickly turned into despair was vividly recalled by him during an interview:

In September 1936, I arrived in Bushehr.with a print of Laili-o-Majnoon. Due to bureaucratic complications, the film print could not be immediately released to screen, and he had to leave for Tehran without it. Government officials' attitude was inexplicably hostile from the beginning and I almost was sorry that he returned home. The authorities did not value cinema as an art form or even as a means of mass communication, and I soon realized that I had to forget about my dream of establishing a film studio in Iran. I even had difficulty getting permission to screen his film, and in the end the movie theatre owners forced us to turn over the film to them almost for nothing.[25]

Sepanta was convinced that vested interests in Iran and elsewhere had colluded to undermine his enterprise:

Representation of foreign companies, who brought in second-hand vulgar films from Iraq or Lebanon, joined forces with the Iranian authorities in charge of cinematic and theatrical affairs to defeat me. This unfair campaign left a lasting and grave impact on my life.[26]

Despite the odds arrayed against him, Sepanta planned to return to India to resume shooting his forthcoming productions Black Owl and Omar Khayyam. However, his mother's failing health prevented him from leaving Iran. The late 30s witnessed a distraught Sepanta doing odd jobs including working in a wool factory in Ispahan. A newspaper that he started in 1943 remained short lived. In the mid-50s he became associated with the United States aid program for some time. Finally in 1965, he shot a few documentaries, which do not reflect the epical style, details and the grandness of scale, Sepanta was known for. Four years later, on March 28, 1969, Sepanta's eventful life came to a tragic end when died of a cardiac arrest in Esafan, where he had spent his last days virtually as a recluse. In addition to more than a dozen films, Sepanta left behind a legacy of eighteen translations and numerous files of the newspaper that he once edited. An Iranian film historian has observed that albeit Sepanta was the only filmmaker who was able to define the aesthetic contours of future Iranian cinema, his contribution remained far from being enduring.

If Sepanta had not faced the obstacles he did and if Iranian cinema had been allowed to develop on a national course, vulgarity would not have prevailed in our cinema for three decades from the 1950s to the 1970s.[27]

This brings us to a crucial question - the relationship between the State and entrepreneurship. In the case of most national cinemas, the State has regulated and directed the motion picture industry both by institutionalizing the mechanisms of finance as well as through censorship. What should be represented on-screen and how has always remained a contentious issue between filmmakers on the one hand and the custodians of public morality and order on the other. The screen thus becomes the battleground for rival ideologies and discourses. There always exists a formidable yet flexible alliance between capitalism (institutional finance, market access, a defined system of arbitration) and the cinematic form (prevailing performative practices, censorship regulations). This is why the State has always viewed the screen as a subversive site.

Like their counterparts in other parts of the world filmmakers in Iran were working under serious constraints. Though monarchs like Mozaffar al-Din Shah and Reza Shah Pehlavi(1925-41)encouraged the use of the cinematograph, the real problem with cinema was not technology but the question of dealing with modernity. Cinema's negotiations with modernity were fraught with unexpected possibilities. For example, by a frontal positioning of the women, cinema could subvert what Ferzaneh Milani has referred to in another context as the "aesthetics of immobility.[28] Cinema also posed the danger of undermining the institutional basis of Iran's feudal monarchy. Instead of providing it with a regulatory framework and bringing cinema into the public sphere, the Iranian state chose the path of disavowal. This situation continued until the Islamic Revolution (1979), by which time the State decided to take on cinema frontally and finally.

Why did success eventually elude Sepanta? His celluloid journey had begun at a time when the import of Iranian films into Iran was comparatively low[29] and attendance in cinema halls constantly rising.[30] One explanation for Sepanta's failure could be that he launched his grandiose project at a time when Iran had haltingly begun its transition toward modernity. Nonetheless, the short-lived Indo-Iranian collaboration revealed the potential that such projects carried for the benefit of both the countries. Had successive Iranian and Indian filmmakers continued to collaborate further, the history of the two national cinemas would have been written quite differently.

References

| 1. |

|

| 2. |

Ibid. |

| 3. |

Such borrowings have been observed in other cinemas. As one film scholar has observed: "Cinema as a medium was informed by what one may term 'intertextual excess' whereby it could borrow from high and low cultural universes at the same time and recombine them in unexpected ways" (M.S.S. Pandian, Tamil Cultural Elites and Cinema: Outline of an Argument, Economic and Political Weekly of India, April 13, 1996, p.950).

|

| 4. |

Hamid Naficy, Iranian Cinema, in Geoffrey Novell Smith (ed.) The Oxford History of World Cinema, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1997, p.672.

|

| 5. |

Ibid. |

| 6. |

The transition of Akkasbashi from a photographer to a cinematographer is evident from a significant entry of king Mozaffar al-Din Shah's travelogue diary:

"[A]t 9:00 p.m. we went to the Exposition and the Festival Hall where they were showing cinematographer, which consists of still and motion pictures. Then we went to Illusion building .in this Hall they were showing cinematographer. They erected a very large screen in the centre of the Hall, turned off all electric lights and projected the picture of cinematography on that large screen. It was very interesting to watch. Among the pictures were Africans and Arabians traveling with camels in the African desert which was very interesting. Other pictures were of the Exposition, the moving street, the Seine river and ships crossing the river, people swimming and playing in the water and many others which were all very interesting. We instructed Akkas Bashi to purchase all kinds of it [cinematographic equipment] and bring to Teheran so God willing he can make some there and show them to our servants." ( www.victorian-cinema.net/akkasbashi.htm.)

|

| 7. |

See my essay, Cinema and Hindi Periodicals in Colonial India (1920-47), in Manju Jain (ed.) Narratives of Indian Cinema, Primus Books, New Delhi, 2009.

|

| 8. |

|

| 9. |

Ibid.

|

| 10. |

|

| 11. |

Ibid.

|

| 12. |

M. Ali, Issari, Cinema in Iran, 1900-1979, 1900-1979, Metuchen: The Scarecrow Press, New Jersey, 1989, p.97.

|

| 13. |

|

| 14. |

For details see Omid Jassal, The History of Iranian Cinema, Rozanneh Publications, Tehran,1995.

|

| 15. |

|

| 16. |

Ibid.

|

| 17. |

Covering the head partly (and not fully) with a hejab constituted nothing short of a sacrilege in feudal Iran. For details, see Shahla Lahiji, Portrayal of Women in Iranian Cinema, An Historical Overview, www.iranfilms/portrayalofwomeniniraniancinema.htm. |

| 18. |

See B.D. Bharucha (ed.), The Indian Cinematograph Year Book of 1938, Bombay Motion Picture Society of India, Bombay 1938.

|

| 19. |

American Cinematographer, June 1932, cited in B.D.Garga, So Many Cinemas, Eminence Designs, Private Limited, Mumbai 1996, pp.71-72.

|

| 20. |

Ibid.

|

| 21. |

Cited in Erik Barnouw and S.Krishnaswamy, The Indian Film, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1980, p.68.

|

| 22. |

Reza Tahami, Iranian Women Make Films, Film International Quarterly, Summer 1994, vol.2, no.3, pp. 4-13.

|

| 23. |

Saeed Kashefi, Film Music in Iranian Cinema, Iran Chamber Society, August 27, 2007.

|

| 24. |

|

| 25. |

Ibid

|

| 26. |

cited in Houshang Golmakani, Stars Within Reach, in Aruna Vasudeva, Latika Padgaonkar and Rashmi Doraiswamy (eds.), Being and Becoming, The Cinemas of Asia, Macmillan Delhi, 2002, p.87.

|

| 27. |

Ibid

|

| 28. |

The concept has been meticulously explored in Farzanneh Milani, Veils and Words: The Emerging Voices of Iranian Women, I.B.Tauris Publishers, London, 1992.

|

| 29. |

|

| 30. |

Ibid

|

Lalit Joshi is a Professor in the Department of History at Allahabad University. His areas of teaching and research include Cultural Globalization and the History of Cinema. He has published extensively in Hindi and English in international and national journals and anthologies. His manual on Hindi Cinema titled HOUSE FULL is going through a second edition. His recent publications include Bollywood Texts (Vaani, New Delhi, 2010) and Mapping India's Cultural Globalization (Orient Blackswan, Forthcoming).

Courtesy: film-international.com

Courtesy: sulekha.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

Top |

|

|

|

|

|