|

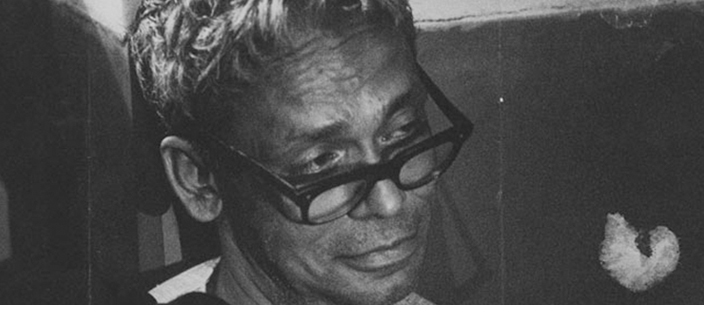

In the cultural sphere of Bengal Ritwik Ghatak (1925-1976) was an exceptional person who evolved a distinct style of filmmaking. It was through the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) that Ghatak entered the world of Bengali culture in 1946. He joined IPTA in 1948. Though he found his ultimate calling in the world of cinema, as a creator, influenced by communist ideology and Marxist world vision during his days with IPTA, he felt he ought to devote himself to the creation of a new culture. And it was a conscious and well-thought-out decision on his part. If we go deeper into the matter, we can safely say that what he became owed largely to the experiences he gained as a member of IPTA. In that sense, these experiences seem to have determined ‘genetically’ his subsequent works as a creator. In the cultural sphere of Bengal Ritwik Ghatak (1925-1976) was an exceptional person who evolved a distinct style of filmmaking. It was through the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) that Ghatak entered the world of Bengali culture in 1946. He joined IPTA in 1948. Though he found his ultimate calling in the world of cinema, as a creator, influenced by communist ideology and Marxist world vision during his days with IPTA, he felt he ought to devote himself to the creation of a new culture. And it was a conscious and well-thought-out decision on his part. If we go deeper into the matter, we can safely say that what he became owed largely to the experiences he gained as a member of IPTA. In that sense, these experiences seem to have determined ‘genetically’ his subsequent works as a creator.

Unless we take cognisance of Ghatak’s participation in People’s Theatre Movement, his comments about contemporary thoughts and theatre as well as the characteristics of people’s theatre movement of that time his subsequent publicised life as a self-destructive person will be inordinately highlighted.1 Though he was not associated with IPTA since its birth, Ghatak, in several interviews, referred to the influence of the birth of IPTA as protest against fascism on his thoughts and creations, shaping his aesthetic intellect. In an interview he gave to ‘Chitrabikshan’, a Bengali film magazine, he clearly charted his transformation: ‘Anti-fascist movement... Japanese attack... bombs... several events happened in quick succession. It was a placid, undisturbed life. All of a sudden some changes gave a big jolt to the ways of people’s thinking. At that time I leaned towards Marxist politics. I had notyet joined IPTA. But I closely followed its activities.... Then cameNabanna, a play staged by IPTA.2 It changed all my thoughts. It was so novel and unexpected at that time. I was drawn towards theatre and became a member of IPTA.’ It is clear from this interview that it was his interest in Marxism and Marxist politics that led him to be a part of IPTA. His belief in Marxism was deepened after he had seen Nabanna directed by Bijan Bhattacharya, and had played a role in the play.

Though Ritwik Ghatak admitted that the brutal aggression of fascist forces, the Second World War, famine in 1943 and the postwar socio-economic complexities in Bengal gave a big jolt to his ways of thinking, it is evident from many of his remarks that it was Nabanna,an original experiment in Marxist aestheticswhich ultimately shaped his dramatic sensibilities and influenced his creations. Ghatak thought that though the People’s Theatre Movement started with plays like Laboratory, Aagun and Jabanbandi, it was Nabanna that gave maturity to the theatre movement.3 Nabanna was written in the background of famine in Bengal in 1943 and all its characters were its victims. Undoubtedly, Nabanna was a social play in which the playwright addressed the entirety of society and its problems from his own viewpoint.4 How far Nabanna was successful in it social commitment was referred to by the communist leader Mani kuntala Sen: ‘Those who turned their faces away from the dead bodies, victims of famine, we were able to make them weep by staging Nabanna.5 Ghatak was convinced that Nabanna was the first play to demonstrate that theatre was not only a part of social struggle but also its weapon.6 About Nabanna Ghatak wrote, ‘It was Bijanbabu who first showed through Nabanna how to be committed to people and how to portray a fragment of reality as an undivided whole on the stage.’7 Ghatak, observing the profound influences exerted by Nabanna among the middle class as well as the peasantry, compared it to Nildarpan by DinabandhuMitra. In an essay entitled ‘Peoples Theatre Movement’, Ghatak wrote: ‘When Nabanna was staged at an All-India Conference in Mymensingh, people were moved by it. Thereafter, at the conference of peasants in Medinipur, people came in thousands to watch it and were equally moved.’8

Though Ghatak considered cinema more powerful than theatre as a means of communicating with the people,9 he none the less never denied his close link with IPTA and theatre. He became known as an actor of IPTA by playing roles in Sambhu Mitra’s Bisarjan and Bijan Bhattachaya’s Nabanna in 1948. He acted in several plays such as, Bhanga Bandar, Bijan Bhattacharya’s Kalanka, Dheu directed by Biru Mukhopadhyay. Bhoter Bhet, a poster play by Panu Pal, Officer, a play adapted from Gogol’s Inspector General and others. But, in the 1950s, we find Ghatak in a different role in IPTA. In 1951-52, besides taking charge of the Central Kolkata Branch of IPTA, he devoted himself to writing plays. Among the five plays written by him, Jwala (1950), Dalil (1952) and Sanko (1953-54) were staged under the banner of IPTA. Apart from acting in plays written and directed by him, he drafted the main policy of IPTA on behalf of its Provincial Draft Preparation Committee in 1951. In the document entitled ‘On the Cultural Front’, Ritwik dealt with the main trends of a people’s theatre movement, the organisational aberrations and deviations of IPTA and the responsibilities incumbent upon the artists and workers of IPTA. In 1954 he under scored a theatre movement as an effective means of liberating the oppressed common people of from the clutches of exploitation. He dreamt of social revolution through the activities of cultural fronts and theatre movements.

In his reminiscences Salil Chaudhuri, the composer and Ghatak’s friend, mentions Ghatak’s devotion, perseverance and honesty as a playwright and an organiser in combatting the aberrations of IPTA so that the cultural movement led by IPTA continued in full force.10 As a member of IPTA he was against the notion of ‘theatre for theatre’s sake’. He would rather have theatre serve people and be faithful to life.11

In the document ‘On the Cultural Front’ Ghatak analysed the main trends of the cultural movement led by IPTA from the 1940s to the middle of the 1950s. What role the workers and artists of IPTA should play as their social and political responsibilities in bringing the proletariat to the mainstream and to what extent they were successful in this regard, formed part of his analysis. However, he dwelt especially upon what should be the relation between the Communist Party of India (CPI) and IPTA, which was founded as its cultural wing. Hence it is relevant to evaluate separately the main trends of IPTA’s cultural activities as they were perceived and analysed by Ghatak.

At some point around 1950 P.C. Joshi, General Secretary of CPI, asked Ghatak to work actively with IPTA in Bengal. CPI had already been banned, and Joshi realised, under these circumstances, that the party should give priority to cultural activities. It is to be noted that when CPI was banned in 1948, it was through cultural activities that the party was trying secretly to reach the masses with its political ideals and programmes. It was in this perspective Ghatak, at the behest of Surapati Nandi, drafted the document ‘On The Cultural Front’ in 1951 on behalf of the Provincial Draft Committee of IPTA’s Bengal Chapter. In this document Ghatak unequivocally stated that it was one of the prime social responsibilities of IPTA to portray the sufferings and aspirations of common people through the medium of art. He thought, ‘It is people who are the heroes of IPTA. Therefore, it should be one of the prime duties of the artists and workers of IPTA to serve the interests of a wide section of people through cultural movements.’12

That Ghatak had great expectations from people’s theatre movement finds mention in his writings. ‘One of the duties which IPTA considers as its prime one,’ Ghatak wrote, ‘is to give expression to people’s resentment and struggles through the medium of different cultural forms. And to express solidarity with those working in the cultural field as one of the comrades in their struggle for people’s freedom.’13 It occurred to Ghatak that a cultural movement was inevitable in so far as it was about organising the toiling masses against fascist aggression and colonial exploitation. At that time the cultural movement led by IPTA took upon itself the social responsibility of expressing the toiling people’s political and socio-economic travails.

In IPTA’s manifesto of 1943 we read, ‘We, writers and artists, singers and dancers, musicians and technicians of the stage and screen, dedicate ourselves anew at this Seventh All India Conference,Bombay of the India Peoples’ Theatre Association to the creation of an art portraying the lives, struggles and dreams of our great people, and their striving for peace, democracy and liberation from all forms of injustice.’ In several articles and interviews Ghatak mentioned the social commitment of the artists and workers of IPTA to finding a solution to the crisis of the starving masses during the great famine of 1943. In one of his interviews he said, ‘It was a placid and undisturbed life in 1940 and 1941. All of a sudden, in 1943, several events like price hike, famine and other such changes gave a big jolt to the ways of thinking.’

India reacted overwhelmingly to the ‘Save Bengal’ initiative by IPTA, together with the shows of Bhukha Hai Bangal, Shahider Dak, Mahamari Nritya and Nabanna. IPTA, through its artistic endeavours, engaged with the crisis of socio-economic and political ills affecting the common people, trying to find the means to its solution. Ghatak, too, in his own way, was engaged in addressing the crisis in the national historical perspective. In 1950, he wrote the play Jwala, which was staged under the banner of IPTA. The play was a portrayal of the social crisis in the context of the complex socio-economic and political situation in the post-Independence era. The play was an assortment of various characters, built structurally around the character of a spirit, whose suffering merged with the suffering of poverty, unemployment, retrenchment, failure to pursue education and pangs of refugee life. A character (Shefali) in the play commits suicide by pouring kerosene on her body and setting herself ablaze, for she could no longer bear the cries of her starving children. The refugee boy Khokan, unable to take on the suffering of seeing his mother and sister raped, endshis life by jumping on the railway track, crushed by a running train. Bhola, the worker of a jute mill, commits suicide because he cannot afford the expenses of medical treatment. The peon, who had an indomitable desire for studies, commits suicide, for he cannot bear the distress of not being able to pay his college examination fees.

The complex socio-economic situation in the post-Independence era jolted the leadership of the CPI into thinking deeply. P.C. Joshi was very earnest about giving expression to the contemporary situation through the medium of theatre. Jwala was the outcome of his initiative. Talking about Jwala Ritwik said, “P.C. Joshi, editor of Indian Way and secretary of CPI, said to me, ‘You take charge of Bengal’. I had already gone through 31 suicide cases, on which was based my reportage ‘Suicide Wave in Bengal’. I sent it to Joshi. Some of the characters in Jwala were drawn from these suicide cases. Each one is a true character. Jwala is really a documentary.”14 Ghatak firmly agreed with August Strindberg’s view that whatever be the mode of expression, Dadaism or Surrealism, one cannot ignore contemporary social background, and it is especially true in the context of the restless times in post-Independence India, Partition riots. It was Ghatak’s intention through Jwala, as a socially committed artist, to sensitise spectators to the brutal reality of contemporary life as opposed to the euphoria generated around India’s Independence, which was, in fact, far divorced from feelings among the majority.

Every character in Jwala was a personification of contemporary social problems. Again, Ghatak gave much importance to bringing the dying forms of our culture back into the mainstream of the IPTA-led cultural movement. And he considered it as one of the principal tasks of the cultural workers of IPTA. In the draft he prepared in 1951 about the main policy of people’s theatre movement, he wrote about the wretched conditions of our folk culture on its way to extinction. In the chapter entitled ‘Culture’ he wrote, ‘In Bengal, criss-crossed by rivers, a village based society, together with all its good and bad sides, flourished along the banks of Ganga, Padma and Brahmaputra, abounding in wonderful folktales and ballads.... Jari,Sari, Bhatiyali, Baul, Kirtan and such other folk music brought colour and flavour to fatigued souls. But, now, this eminently rich folk culture has lost its primordial beauty, and is on its death-throes. The present is in limbo, divorced from its roots, looking for its fulfilment in the West.’15 As A door said ‘Ritwik wanted to integrate our marginal cultural forms, facing extinction under the pressure of bourgeois culture, into the mainstream of middle classes’ practice of culture as indigenous tradition. This found expression in his films in the form of the marginal cultures of the Oraons and other tribes of Bihar and Purulia in their various articulations. On the other hand, the use of Bengal’s traditional wedding songs, Bhatiyali, Baul enriched his creations.’ 16

A question may be raised here why Ghatak went back, so ardently and repeatedly, into the mainstream of our indigenous culture to give it a fresh lease of life in his creations. Perhaps, we can find its answer in Kumar Shahani’s reminiscences as Ghatak’s student at the Pune Film Institute, which he recounted to the present researcher. At that time Ghatak laid emphasis on the use of indigenous culture, and his experiences thereof, in his creation. At the same time he would say that it was the Partition which determined his quest for indigenous symbols.17 In the manifesto of IPTA in its earliest years the recovery of our dying and marginal forms of art and culture was given importance.18 The marginal artists such as Panchanan Das, Jamshed Ali, Rameshwar Kariyal and others participated in the IPTA-led cultural movement, yet, at the same time, establishing their distinct identities by their own ways of practising art. However, Ghatak realised that IPTA became indifferent, from the end of the 1940s, to the recovery of folk culture and bringing marginalised artists of IPTA’s cultural workers together. IPTA activist Sudhi Pradhan, too, echoed Ghatak’s thoughts, ‘IPTA’s theatre activities in Bengal were largely confined to urban areas. Their impact on rural areas was limited. Also, they were less interested in folk culture.’19 When, in 1951, Ghatak drafted the Guiding Policy of IPTA, he called upon IPTA’s cultural workers to forsake their narrow and indifferent attitude and bring back thousands of obscure national poets into the mainstream of cultural life to rejuvenate folk culture as a means of embodying sorrows and sufferings of our people. He wrote: ‘Friends of IPTA will set about discovering folk poets on the verge of oblivion, learn from them the ways to reach deep into people’s heart and help them to achieve excellence in their vocation.’20

However, it has to be also said that the use of indigenous art forms in his films bears the stamps of Ghatak’s original approach. Undoubtedly, the aim of Ghatak as an artist was to evaluate contemporary reality from the standpoint of Marxism to get at its essence through his creations and spread it among the masses. He realised that it is difficult to reach the masses, especially those in villages, unless one takes recourse to indigenous structural forms. That is why Ghatak always endeavoured to fuse modernity with ancient tradition in his creations. When Ghatak was associated with IPTA, he gave importance to the rapprochement of the dying and marginal forms of folk culture (ChhayaNritya, ChhauNritya, KabirLarai, PutulNach, Baul, Kirta’, Bhatiyali, Bhawaiya, etc.) with the so-called refined middle-class culture. Ghatak realised that these forms like PutulNach, ChhauNach, Chhaya Nritya and others have immense potential in sensitising the masses to the issues of democracy. He paid compliments to Uday Shankar’s individual efforts in this regard. However, he pointed out that the dancers and danseuses of IPTA failed to carry forward Uday Shankar’s experiments.21 In the draft of principal policy he wrote on behalf of IPTA, Ghatak appealed to the artists and workers of IPTA in these words - ‘It is not only important to point out the distorted representation of social reality in the thriving trends of theatre in the city, but also to rid them of such manifestations, underscoring theatre as a vehicle of conveying social values. It is equally important to go close to our ancient tradition, trying hard to survive through Jatra, Palagan, Gambhira, and rejuvenated it with contemporary social themes, thereby rehabilitating its status with full honour and, at the same time, setting forth a new trend.’22 That Ghatak was engaged in recovering the marginal folk cultural is evident in his creations. In 1955 he made a documentary on the Oraons, in which he depicted their life in terms of cultural practices. Ghatak said, ‘In it I showed the grand ensemble of many dance forms such as Koha, Benja, Khatura, Chali, Bechna, Lugari and others, which embody the whole cycle of birth, hunting, marriage, death, worship of ancestors and rejuve nation.’23

As a social-realist artist Ghatak believed that culture is not divorced from politics; political movement and cultural are inextricably linked. Cultural movements must follow politics as its commitment, and artists and workers of IPTA should make common people aware of the contemporary reality. 24 To illustrate this point Ghatak referred to the well-known song ‘EkbarBiday De MaaGhureAashi’, written by an anonymous poet. The poet acutely felt the suffering of the oppressed people of our enslaved nation, which he expressed in his poem from a martyr’s viewpoint, severely indicting the exploitation by imperialist masters.25 It is worth mentioning that theMumbai session of IPTA in 1943 declared in the backdrop of the fascist aggression and horrors of the Second World War, ‘It is the task of the movement to enthuse our people to build up their unity and give battle to the forces ranged against them with courage and determination and in the company of the progressive forces of the world. It is our task to aware people about the crisis it is necessary to involve them in a progressive movement, because as a united force they are invincible.’26 Ghatak also felt that it is easier for the common people to understand and react immediately to political ideology and problems couched in artistic forms than those presented as such. In the draft written on behalf of IPTA he underscored, ‘IPTA, engaged as it is in freedom struggle, considers it its duty to create works of art representing the interests of each and every class. Consequently, these works of art may as well be called those of the freedom-aspiring democratic camp. IPTA is its guiding beacon in this respect. Therefore, it devolves upon itself to:

- Unite in the interest of national freedom struggle;

- Engage all the arts to fortify political struggle;

- Keep in mind the interests of the common masses and creategenuine people’s art and disseminate it across all tiers of society.’27

In his discussion about how the artists of IPTA could inspire people with idealism, Ghatak cited the works of Brecht and Gorky as examples of political literature. He thought, ‘Gorky’s principal vision consistsin his philosophical position in relation to political realism.’ Ghatak considered Gorky’s Lower Depths as a successful political play,for, in it he bared the false notions about the poverty-stricken and oppressed people and succeeded in inspiring the proletariat with political and socialist thinking by delving deep into the truth.28 About Brecht he remarked, ‘After the First World War, when revolutionarypolitical situation was created and there was a tide of changes inall spheres of life, he presented to the spectators the revolution aryi deals of the new era in a magisterial fashion and truly carried out theduties of a political artist.’29 In an interview Ghatak gave to Kalpana Biswas, it became clear that the artists of IPTA had been trying, fromthe 1940s till the middle of the 1950s to enlighten the masses about the political turmoil’s of that period. Ghatak referred to IPTA’s activerole in exposing the true nature of colonial rule in pre-Independence India, or in restoring Hindu-Muslim unity in a riot-devastated Bengal in 1946.30 The artists and workers of IPTA also engaged themselves in depicting the miseries of the people in post-Partition days and set about proving the hollowness of the euphoria generated after Independence. Ghatak showed much respect to those endeavours. In this regard he referred particularly to two songs: One by HemangaBiswas’ Mountbatten Mangalkabya and the other Naker Badale Narun Pelam composed by Salil Chaudhuri.31

To Ritwik Ghatak the riots in 1946 and Partition in 1947 were two events that tore apart the fabric of social life. In the draft he wrote in 1951, he emphasised on making people aware of the post- independence political situation. He wrote, ‘neither exploitation nor miseries have become less. Only there is confusion in the national liberation struggle. And the country is divided into two parts, hostile to each other. Freedom has already lost its illusory sheen. Conditions are getting worse day by day. A vast section of the working people of our country has been rendered homeless. A section of the peasantry, small artisans, small traders and a section of the lower middle class have turned refugees. They are like drifting weeds in a stream.... IPTA holds the view that we have not attained freedom onAugust 15, 1847; on the contrary, we are now into newer confusions.’

The success of the national liberation struggle has suffered a setback for a while.’32 Ghatak wrote the plays Dalil (1952) and Sanko (1953) in order to enlighten the masses about the complex political equation behind Partition and the socio-economic and political situation in post-Partition Bengal. At the Mumbai session in 1953, Dalil won the first prize. In the introduction to Dalil Ghatak wrote:‘The uprooted people scattered all around. Directionless, they move about, not knowing where to go. And, amid all this, the cruel society and traitorous leaders go on playing ducks and drakes with them. They are a bewildered lot.... Divided Bengal is crying out and the Bengalis, their tradition and their culture are the same, indivisible since distant past, and so it will be till distant future.... History does not forgive Mir Zafars. I felt the need to reiterate it loudly. These aremy definitive words.’33 At the beginning of the play Dalil we see Haren Pundit of the village listening to the declaration of the partition of the country on radio. If it comes true, he has to set out in the night, for, he thinks, Muslims cannot be trusted. Amid apprehensions of being uprooted from one’s homeland, one hears ‘over there lies Hindustan’ like a beacon of light in darkness.34 Ghatak saw the endangered existence of the people of East Bengal, looking for peace and security amid the complex turns and twists of politics, through Khetu’s words, ‘Wherever is gone the peace and security of the country? All of a sudden there is division among its own people. I don’t understand why there is this disquiet.’ 35 ‘Dalil’ was a precursor to his films, both them atically and stylistically, in which Ghatak dealt with the bloodied history of Partition. Dalil was not what we mean by a complete play. In this play, rather, the destiny of the Bengalis, ousted from their home steads, moves inexorably towards its denouement, like the Padma flowing towards its ultimate destination. The play oscillates between extremely unfavourable circumstances on the one hand and the firm belief in victory, on the other. In fact, time is its protagonist. The turbulent times perturbed Ghatak and made him reflect deeply.

In the poem Dharmamoha, Rabindranath Tagore said, ‘When you are intoxicated by the poison of religion, you turn blind. You kill or get killed.’ This is precisely what constituted the central theme of Ghatak’s play Sanko. Post-Partition Bengal was a theatre of fratricidal political violence which jeopardised the security of both Hindus and Muslims.

The political forces, representing both Hindus Muslims, were out to gain political mileage by instigating the confused and frenzied young people to indulge in genocide. Sanko was a political play set in this backdrop, in which Ghatak foregrounded the distorted mind exulting over carnage. In Sanko Ghatak showed that the opportunist politicians had profited much by playing on religious sentiments, but for those confused young people, marked as rioters, the way back to social life was completely sealed. They were condemned to a life of despair and gloom, repenting of their inhuman crimes. In the 1940s and 1950s the artists of IPTA set about, through their work, arousing people’s political consciousness about contemporary social conflicts. Ghatak, as an artist of IPTA, subscribed to such activities, but his originality lies elsewhere. He held the view that a work of art, political in intent, is not merely an artist’s strident utterance. This utterance acquires density only when the artist’s political statement is transfigured by analysis of events and social canvas. In his works Ghatak achieved a fusion of farsightedness based on ground reality and social and political consciousness.As an artist subscribing to Marxist viewpoint, Ghatak believed, ‘Everything is class-based; if you drop the issue of class you end up by achieving little.’36

The proletariat, for Ghatak, constituted the basic foundation of society, and he looked forward to an exploitation-free society through the rapprochement between the class-consciousness of the educated middle class and that of the vast majority of working people.37 At the founding conference of IPTA held in Mumbai in 1943, where main emphasis was given to build unity between educated middle and working class people simultaneously IPTA consolidated voice for the release of national leaders and criticised against fascism colonial exploitation and food-hoarders. There explained ‘In this connection we are greatly encouraged to find that under the stress of present situation, there has been developing spontaneously from among the masses, particularly the kisans (farmers) andworkers, a movement of songs, recitations and dancers rousing the people to action against the fascist aggressors and the food-hoarders and for the release of national leaders and the achievement of a national government. It is essential that this spontaneous movement should be organized and co-ordinated by All India People’s Theatre Movement.’38 As a class-conscious artist, Ghatak observed that it was not just a matter of taking note of a few events. Rather, it devolved upon the artists of IPTA to focus their attention on a broader perspective. They must take cognisance of the unrelenting onslaughts against the working people and the slaughter of humanism at the hands of the bourgeoisie and the colonial masters, with exploitation as their potent weapon.

Hence, the main task of the artists of IPTA consisted in uniting the working people, bringing them into the mainstream of the cultural movement and assuring their victory against colonial exploitation and the onslaughts of the bourgeoisie. In this context, Ghatak identified the organised workers and peasants as the basic foundation of society, quoting Stalin’s thoughts regarding the proletariat,39 Ghatak said, ‘We know from the quoted sayings of comrade Stalin: humanism is a banner which our bourgeoisie is deserting more and more today. It is perfectly certain that no other class is historically capable of holding the flag high other than the organised proletariat.’ 40 Judging the trends of national and international events, Ghatak well understood that the proletariat’s class struggle was the guiding force of the democratic revolution in the underdeveloped countries. Hence, one of the main tasks of the artists of IPTA consisted in injecting revolutionary sprit and ideals into the movement by the proletariat.41 Ghatak paid much importance to reaching out to the workers and peasants through cultural practices couched in their own language in order to infuse them with revolutionary ideals. In the document ‘On the Cultural Front’, Ghatak said, ‘While writing for the working people in any genre of art and culture, the artists of IPTA should keep it in mind that these works depict the struggle of the oppressed working people against exploitation and deprivation and express their yearnings and resentment.’

In this context Ghatak referred to the creative works of Subhas Mukhopadhyay, Hemanga Biswas, Sukanta Bhattacharya, Salil Chaudhuri and others. About Sukanta, who was a follower of Marxist thoughts, Ritwik wrote, ‘When Sukanta wrote poems for the working people, he set aside his middle class identity to look at society from their viewpoint. In fact, every line of his poems expresses the struggle of the proletariat against colonial exploitation, and also exploitation and deprivation in a society ruled by the bourgeoisie, which stoked the fires of rebellion like the sparks of Promethean fire.’42 Ghatak wrote. ‘...and it will be interesting to note our Sukanta’s attitude. He opens his heart in the following poem (which comrade Salil Chowdhury has so ably set to music and popularized):

“It’s revolution now, revolution all over,

My task is to chronicle it day by day,

Look at all those of the humiliated and enslaved

Rising apace.

I take my place behind their ranks,

I live and die with them.

And that’s why I go on writing chronicle of the revolution all over.

Bold, clear-cut declaration, a manifesto unto the world.’ 43

Ghatak held the belief that it was essential for the artists of IPTA to share a common platform with the proletariat and forge a bond with them, in order to understand the culture of the working masses and also to bring as many artists as possible under the umbrella of IPTA.44 This is precisely what is expressed in artistic terms in Amar Lenin, a documentary made by RitwikGhatak. In it, although madein 1970, he went back to the 1940s and 1950s when the artists of IPTA felt the need to inculcate the spirit of revolution among the masses through cultural movement. The plot is set in the 1940s-1950s whenthe artists of IPTA were staging a play in villages, which was inspired to them. A young man, motivated by the play, set about establishing peasant’s rights in his village and inspiring his fellow-brothers to unite and struggle for a social system free from exploitation.

The first bulletin of IPTA explained ‘...with the growth of Kisan and working class movements, writers and artists from among the submerged masses began to be stirred by the new hope and faith in their classes engendered by these movements. Village bards and factory workers began to compose and sing their own songs of hope and defiance, but the further organization of these developments into theall India movement was yet to be achieved.’ From the position of an artist of integrity Ghatak felt a note of discord in this declaration of IPTA - somewhere it missed the spirit of camaraderie between the working masses and the artists of IPTA. In this, Ghatak was not mistaken. Subsequent events corroborate his observation. Though from the latter part of the 1940s, the resentment of workers and peasants found expression in the works of art by artists of IPTA in the context of naval revolt, workers’ strikes, strikes by jute mill workers and ‘Tebhaga’ movement, since the first part of the 1950s the middle class was noticeably moving away from the working masses.

Ghatak pointed out that many artists or cultural activists were not members of the Communist Party of India, though they felt the need to link the IPTA-led cultural movement with the contemporary communist movement. When, in 1948, Ghatak joined IPTA, he felt drawn towards the Marxist political movement. He did not become a member of the party, but, as a cultural activist, he carried out the duty of an active member of the party.’ In his reminiscences Debabrata Biswas, one of the eminent artists of IPTA, recalled, ‘I had the good fortune of getting acquainted with many famous political leaders of that time in a room on the third floor of a building at 48 Dharmatala Street. Discussions were held about politics and culture, and the directions politics and culture had to pursue. Though I was not a member of the party, I felt in these discussions a yearning from the heart.’

Debjani Halder did her graduation and got her master’s degree in history. Then she shifted to abroad interdisciplinary field across the social sciences. She got her PhD in Film Studies from Jadhavpur University. Shewas a European Excellence Research Fellow of Central EuropeanUniversity, Budapest and is now a Fellow, Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, Shimla

Bibliography

Adhikari, Gangadhar, 1942 ‘From Peace Front to people’s War’ CPI publication. New Delhi

Adhikari, Gangadhar, 1947 ‘Resurgent India at the crossroads’ CPI Publication. New Delhi

Biswas, Hemanga, 1980‘Gananatya Andolane Aamar Gaan’, Mass Singers Publication, Kolkata,

Biswas, Debabrata, 1389 (Bengali calendar). ‘Bratyajaner Ruddha Sangeet’, Karuna Prakashani, Kolkata

Bandyopadhyay, Karuna, 2002. ‘Aar EkSarbajaya’, Thema, Kolkata

Bandyopadhyay, Saktipada, 1981. ‘Prasanga Gananatya’, Ganaman Prakashan, Kolkata

Chattopadhyay, Gautam,1986 ‘The Almost Revolution’ A case study of India in 1946’, PPH New Delhi,

Chattopadhyay, Kunal, 1996. ‘Tebhaga Andoloner Itihas’, Progressive Publishers, Kolkata

Chattopadhyay, Mangala Charan, 1358 (Bengali calender). ‘Megh BristiJhar’, KavyaKon, Monfakira, Kolkata.

Chaudhuri, Salil, 1975. 1978 ‘Ghoom Bhangar Gaan’, Saraswat Library, Kolkata

Chakraborty, Rathindranath (ed.), 2001 ‘Ritwik Ghataker Natak Sangraha’, Paschimbanga Natrya Academy, Kolkata

Das, Suranjan, 1991 ‘Communal Riots of Bengal: 1905-47,’ OUP, Delhi

Dasgupta, Shiladitya and Bhattacharya, Sandipan, 2001 ‘Interview with Ritwik’, Dipayan Publication, Kolkata

Das, Dhananjay (ed), 2003 ‘Marxbadi Sahitya Bitarka’, Kolkata, Karuna Prakashani, Kolkata

Ghatak, Ritwik, 2006 ‘On the Cultural Front: A Thesis submitted by RitwikGhatak to the Communist Party of India in 1954’, Ritwik Memorial Trust, Kolkata

Goswami, Arjun (ed), 2006, Uttal Shat-Sottor, Rajniti, Sanskriti Chayanika’, Thema Publication, Kolkata

Goswami, Parimal, 1994 ‘Mahamanwantar’, Printers and Publishers, Kolkata

Ghosh, Ajit Kumar, 1970 ‘Bangla Nataker Itihas’, General Printers and Publishers. Kolkata

Ghosh, Purnendu, 1987‘Tebhagar Smriti’, Setu Sahitya Parishad. Kolkata

Ghatak, Ritwik, 1382 (Bengali calendar). ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichhu’, Dey’s Publication, Kolkata

Joshi, P.C., 1942 February ‘Forward to Freedom: India in the War of Liberation’, CPI Publication, Delhi

Joshi, P.C., 1945 ‘Communists and Congress’, National Book Agency. Kolkata

Moitra, Jyotirindra, 2006 ‘Nabajibaner Gaan’, Monfakira. Kolkata

Mitra, Sambhu, 1971 ‘Prasanga Natak’, Sanskrita Pustak Bhandar. Kolkata

Mukhopadhyay, Hirendranath, 1986 ‘Tari Hote Tir’,Manisha, Delhi

Mukhopadhyay, Saroj, 1985 ‘Bharater Communist Party O Aamra’, Vols 1&2, National Book Agency, Kolkata

Plekhanov, 1979‘Art and Social Life’, Moscow, Progress Publishing, Moscow

Pradhan, Sudhi, 1989 ‘Nabanner Projojana O Prastab’, Kolkata, Pustak Bipani. Kolkata

Ranadive, B.T., 1984‘The Role Played by Communists in the Freedom Struggle’, ‘Social Scientist’. Delhi

Rao M.B. (ed), 2008 ‘Documents of the History of the CPI’ Vol. VII, PPH. New Delhi

Roy, Anuradha,1987 ‘Challisher Dasaker Banglay Ganasangeet Andolan’, Papyrus,.Kolkata

Roy, Anuradha, 2000‘Sekaler Marxiya Sanskriti Andolan’, Progressive Publishers. Kolakta

Roy Chaudhuri, Sajal, 1990 ‘Gananatya Katha’, Ganaman Prakashan, Kolakata

Sehanabish, Chinmohan, 1986 ‘46: Ekti Sanskritik Andolan Prasange’, Research India Publication, Delhi

Thakur, Soumendranath, 2007 ‘Fascism’, Monfakira. Kolkata

Notes/references: Notes/references:

| 1. |

Biswas Hemanga, 1986 ‘Smritir Chinnapatra’ (Bengali), in ‘Nilrohit Patrika’, Ritwik Ghatak Issue, first edition, first year, Kolkata, p. 138.

|

| 2. |

Interview with Ritwik,1973 ‘Chitrabikshan’ (Bengali), Kolkata, p-56.

|

| 3. |

GhatakRitwik, 1382 (Bengali calendar). ‘Bijan Bhattacharya: Jibaner Sutradhar’ (Bengali), in Ghatak, ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichhu‘, Dey’s Publishing House, Kolkata p. 22.

|

| 4. |

Interview with Ritwik,1973 ‘Chitrabikshan’ (Bengali), Kolkata, p-58.

|

| 5. |

Sen Mani kuntala , 1981 ‘Sediner Katha’ (Bengali), Nabapatra Prakashani, Kolkata p. 48.

|

| 6. |

Ghatak Ritwik, 1973 ‘Chitrabikshan’ (Bengali), Kolkata, p-56

|

| 7. |

Ghatak Ritwik, 1382 (Bengali calendar) ‘Bijan Bhattacharya: Jibaner Sutradhar’, in ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong AaroKichu’, Dey’s Publishing House, Kolkata, p 22-23.

|

| 8. |

Ghatak Ritwik 1382 (Bengali calendar), ‘GananatyaAndolanPrashange’ ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichu’, Dey’s Publishing House, Kolkata,, p. 16.

|

| 9. |

Interview with Ritwik, 1973, ‘Chitrabikshan’, Kolkata, p-56.

|

| 10. |

Interview with SalilChaudhuri by the research scholar Kalpana Biswas in 1984. I heard the taped interview from her personal collection on 4 March 2010. Salil Chaudhuri said, ‘Ritwik, Mrinal and I met occasionally in a restaurant near Kalighat and talked about theatre and literature. Ritwik wrote and from time to time came up with fresh plots which he discussed with us. In our talks would crop up the organisational aspects of IPTA. He was very serious and thought about the trends of theatre movement and the tasks of the theatre activists and artists. It was Ritwik who first introduced changes in the techniques of theatre in IPTA.’

Ritwik Ghatak, 1382 (Bengali Calendar) ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichhu’, Dey’s Publishing House, Kolkata, p-87

|

| 11. |

ibid

|

| 12. |

Ghatak Ritwik ‘Natak Sambandhe’ 1382 (Bengali, Calender), ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichhu’, Deys Publishing House pp. 17-18.

|

| 13. |

ibid

|

| 14. |

Ghatak Surama 1991, ‘Padma Theke Titas’ (Bengali), ‘Anust up’, Kolkata, p. 14.

|

| 15. |

Ghatak Ritwik, ‘Loksanskriti’ 1382 (Bengali Calender), in ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichhu’, Deys Publishing House, pp. 42-43.

|

| 16. |

Interview with Adoor Gopala krishnan at his residence in Kerala, 2 September 2008.

|

| 17. |

Interview with Kumar Sahani at Delhi University Housing Complex, 7 September 2008. The filmmaker Sahani gave a psychological explanation of Ritwik’s attachment to indigenous ancient culture, ‘Ritwik’s search for the roots of ancient culture lay in his sufferings because of Partition. The Partition forced him to leave the world, the cultural ambience he lived in and so familiar about - ‘Bhatiyali’ and ‘Sari’ songs and Bengali spoken with a typical intonation along the banks of the river Padma. This cultural rootlessness, in a way, drove Ritwik to delve deep into traditional culture in order to retrieve it. Thus, when Ritwik took charge of IPTA’s Central Kolkata branch, the retrieval of folk culture was a recurrent theme in the documents he wrote.’

|

| 18. |

Pradhan Sudhi, 1989 ‘Marxist Cultural Movement’, Vol 1, National Book Agency, Kolkata pp. 20-21.

|

| 19. |

Ibid. p. 254.

|

| 20. |

Ghatak Ritwik, 1382 (Bengali Calender) ‘Moolnitir Khasra’, in ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichhu’ Dey’s Publishing House, Kolkata p. 44.

|

| 21. |

ibid p-47

|

| 22. |

Ibid, p. 44.

|

| 23. |

Chitrabikshan’, August-September 1973, Kolkata p-53

|

| 24. |

Ghatak Ritwik, 1954 ‘Communist Artist and the Party’ in ‘On the Cultural Front’: A thesis submitted to the Communist Party of India, Published by Ritwik Memorial Trust, Kolkata, p. 37.

|

| 25. |

Ibid.

|

| 26. |

Pradhan Sudhi, 1989, All India People’s Theatre Conference, ‘Draft and Resolution’, in the book of ‘Marxist Cultural Movement in India’, Vol. 1, National Book Agency, Kolakta, p. 151,

|

| 27. |

Ghatak Ritwik, 1382 (Bengali calendar) ‘MoolnitirKhasra’, in ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichhu’, Dey’s Publishing House, Kolkata, p. 151,

|

| 28. |

Ghatak Ritwik, 1954 ‘Communist Artist and The Party’, in ‘On the Cultural Front’ – A thesis submitted by Rtiwik Ghatak to the Communist Party of India, Published by Ritwik Memorial Trust, Kolkata, p-78

|

| 29. |

Ritwik Ghatak, 1382, (Bengali Calender) ‘Brecht O Aamra’ (Bengali), in ‘Chalach chitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichhu’ Dey’s Publishing House, Kolkata, pp. 20-21.

Ritwik Ghatak interviewed by Kalpana Biswas in February 1974. I heard the taped interview from her personal collection on 4 March 2010.

|

| 30. |

Ibid.

|

| 31. |

Ghatak Ritwik 1382, (Bengali Calender), ‘Moolnitir Khasra’ in ‘Chalachchitra Manush Ebong Aaro Kichhu’, Deys, Publishing House, Kolkata, p. 50.

|

| 32. |

Ghatak, Ritwik, 1953 Introduction to the play ‘Dalil’. The original script of the play is included in Rathin Chakraborty (ed), ‘Ritwik Ghataker Natak Sangraha’, Kolkata, Paschimbanga Natya Academy, p-19

|

| 33. |

Ghatak, Ritwik, 1953 ‘Dalil’ (Bengali), Act I, Scene I. The original script of the play is included in RathinChakraborty (ed), ‘Ritwik Ghataker Natak Sangraha’, Kolkata, Paschimbanga Natya Academy,

|

| 34. |

Ibid.

|

| 35. |

Ghatak Ritwik, 1976, Interview published in Bijnapan Parba’ Ritwik Issue, kolkata, pp. 109- 110.

|

| 36. |

Ghatak Ritwik, 1976, Interview published in Bijnapan Parba’ Ritwik Issue, kolkata , pp. 109- 110.

|

| 37. |

Pradhan Sudhi, 1986, The All India People’s Theatre Conference 1943’, in the book of ‘Marxist Cultural Movement’, Vol.1, National Book Agency Kolkata, pp. 129-130.

|

| 38. |

Ghatak Ritwik 1954, ‘Communist Artist and the Party’ ‘On The Cultural Front’ published by Ritwik Memorial Trust, Kolkata, p. 41,

|

| 39. |

Ibid, p-39

|

| 40. |

Ibid, p-42

|

| 41. |

Ghatak Ritwik 1954, ‘Communist Artist and the Party’ ‘On The Cultural Front’ published by Ritwik Memorial Trust, Kolkata, p.42

|

| 42. |

ibid

|

| 43. |

Ibid, p- 47

|

| 44. |

Pradhan Sudhi, 1986, Indian People’s Theatre Association, Annex. 8/Bulletin No.1, July 1943 , in the book of ‘Marxist Cultural Movement’, Vol.1, National Book Agency Kolkata, p- 128.

|

Ghatak was a great filmmaker but it would be questionable to make an equation between his greatness and his political leanings. The essay brings out certain attitudes among the left – to which Ghatak was ardently attached – which bear questioning. One of the most fundamental ones is the assumption that 1947 brought nothing to India, conferred no advantages. There is little doubt that since the struggle for freedom was led by the bourgeoisie, independence hardly benefitted all Indians equally. Being dissatisfied with it and looking to what it might have been is acceptable but to completely decry its gains is unreasonable. Ghatak and the left eulogized Lenin, Stalin and the Russian revolution and this leads us to wonder if they believed that the ‘proletarian revolution’ actually benefited everyone. How did Ghatak respond to Stalin’s show trials (1936-38), the subsequent executions and the gulags, which decimated the Communist Party, one is led to wonder. I propose that Ghatak’s seemingly unquestioning adherence to Communist doctrine till so late in his life should not be regarded so sympathetically, as is normally done; it needs also to be interrogated. Utopian principles held apriori and which remain unmoved by historical experience cannot be considered admirable today, in the light of so much bloody history.

Editor

Courtesy: Ritwik Ghatak

|

|