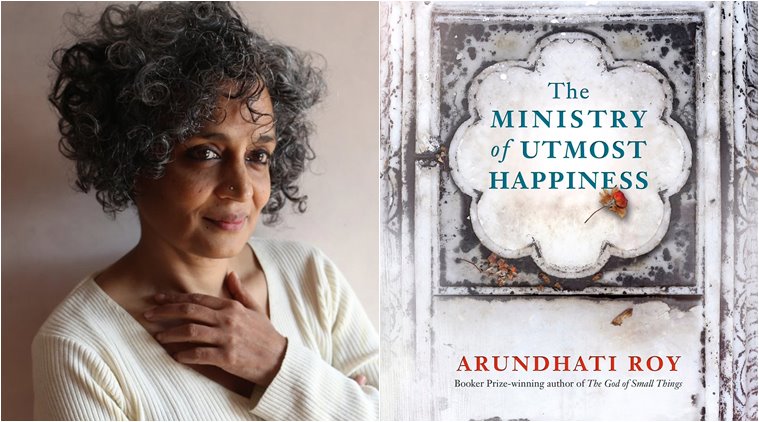

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness

by Arundhati Roy

A new novel by Arundhati Roy is bound to become international news and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness has already been widely reviewed. After her first novel The God of Small Things (1997) became a worldwide bestseller (and also won her a Booker Prize) Roy became a political essayist, taking up radical causes not only in India but also internationally – issues like the nuclear tests and the Sardar Sarovar project in India and America’s military engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan. Her political essays which appeared in magazines and periodicals were later anthologized and one of the earliest collections appeared under the title The Algebra of Infinite Justice (2001). Her virulence as a radical polemicist has given her a large following in India as well as a host of detractors; if one should name that one person over whom the right and the left take fiercely conflicting positions, that person could well be Arundhati Roy. Issues like Maoism and militancy in Kashmir, where she takes a bold stand against the nation-state are essentially those where opinion is most sharply polarised and her writing inevitably provokes extreme responses.

In her first novel Roy had not yet emerged the political polemicist that she was later to be but there are aspects to it that reappear in her polemic. The God of Small Things is partly autobiographical and Roy creates a number of vivid characters who, one guesses, are caricatures of people once close to her. Roy is gifted with an exceptionally neat turn of phrase but she emerges principally as someone who nurses fierce antagonisms and uses her writing skills to hit out. She has the capacity to use her pen to hilarious and usually vicious effect through caricaturing and sarcasm – and if her targets are personal acquaintances, carefully given other names in her first novel, they become public figures in her later writing. Also, while Roy mightdeny this supposition, she introduces a character (Rahel)who is apparently herself as an adolescent girl and then describes her appearancein away that suggests deep narcissism:

“… She was in jeans and a white T-shirt. Part of an old patchwork bedspread was buttoned around her neck and trailed behind her like a cape. Her wild hair was tied back to look straight though it wasn’t. A tiny diamond gleamed in one nostril. She had absurdly beautiful collarbones and a nice athletic run.”

In case of any doubt that ‘Rahel’ is pictured as Roy appears to herself (and the world at large), wild hair and collarbones are among the physical attributes given to the female protagonistof The Ministry of Utmost Happiness as well. But Roy inserts herself conspicuously into most of her writing, even her essays - though not by describing herself physically like this.

Arundhati Roy is a political essayist with radical left-wing leanings but rather than use the scalpel of analysis, she is prone to belabour her targets with every verbal weapon at her disposal. She reiterates in interviews that her fiction and her political essays are part of one whole and one is inclined to agree. But what this means is that she is that she uses literary devices (irony, mockery) instead of reasoned argument – i.e.: she has rarely anyanalysis to offer on any issue and what she brings to it is mainly impassioned polemic. She is never at a loss for words and invective and sarcasm flow freely from her pages. While writing about Bill Clinton’s political doings, for instance, she can lewdly invoke his well-publicised sexual conduct, albeit in a round about literary way. One might take exception to her approach but since she is always for the victims, doing so puts one on the wrong side, making one sound trite and uncaring. A critique of political polemic can be easily twisted to mean a defence of the indefensible.

Another feature of her political essays arethe personal elements slipped in. ‘The Greater Common Good’, as essay about the Sardar Sarovar Project, begins with the following paragraph which runs to only one sentence: ““I stood on a hill and laughed out loud.”What made her ‘laugh out loud’ was apparently her understanding of the manifold ways in which the state victimises the helpless, and her laughter is mirthless. But what one finds significant is the way she pictures herself in relation to the big issue, privileging her own position, making herself larger in stature.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is not autobiographical like The God of Small Things but Arundhati Roy nonetheless contrives to place herself at its centre. The novel is difficult to describe and some reviewers have (not unfairly) found it messy. But to convey its sense, it takes virtually every major issue in the past two decades (many of which Roy has written about) and weaves them into a narrative, taking the viewpoint of the victims of society. The issues brought into focus include separatism in Kashmir, Maoism and the Adivasis, anti-cow-slaughter vigilantism and the communal violence, the Narmada BachaoAndolan, the Gujarat riots, the plight of the Bhopal victims, as well as perennial ones like police brutality and caste oppression.

The novel is in two separate threads, brought together rather haphazardly. The protagonists in the first strand are, chiefly, a Muslim hijra named Anjum, a ‘chamar’ who has taken a Muslim identity and goes by the name of Saddam Hussain because of his admiration for the Iraqi dictator, and a child born to a Maoist dalit woman who dies soon after her child is born. This first sub-narrative (which seems to take inspiration from Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, 1981) is set in old Delhi and deals with underclass life in the capital over two decades or so, using a descriptive style that draws heavily from magical-realism. Locating it in Delhi means that Roy can raise most of the issues publicised at Jantar Mantar and caricature every politician’s attributes over the period. Rushdie, one recollects, described Sanjay Gandhi (without naming him) as ‘Labia-lips’ and Morarji Desai as a ‘urine-drinking dotard’.

The problem with such lampooning is that personal attributes have little bearing on a politician’s real significance and it therefore illuminates nothing. The same is true of Roy describing Atal Bihari Vajpayee (also without naming him) as a ‘lisping poet’and mocking the pauses in his speeches. Politician-bashing is a favourite pastime of a section of readers and Roy panders to it. But to be fair, Roy sometimes scores politically in her caricaturing and Manmohan Singh as a ‘trapped rabbit’ has some bearing on his conduct as a statesman. Here is a comical description of Arvind Kejriwal (renamed Aggarwal) comparing him to the character Anjum: “He, a revolutionary trapped in an accountant’s mind. She, a woman trapped in a man’s body.”

The second strand in The Ministry of Utmost Happinessis devoted mainly to militancy in Kashmir and this is where Arundhati Roy inserts herself securely as a character. The story here revolves around a woman S Tilottama, and three men who (like Roy) all studied architecture in Delhi. The woman is from Kerala and part Syrian Christian like her creator. Roy makes her the child of a liaison of the same kind as in The God of Small Things – between an upper-class Christian woman and a dalit labourer. Needless to add, all three men love Tilottama.

The three men in Tilo’s life are a Bengali (an official in the Intelligence Bureau in Kashmir), a Tamil Brahmin journalist in Kashmir, the son of a diplomat,who gives Kashmir ‘unbiased’ coverage, and a Kashmiri named Musa who joins the militants when his wife and baby daughter are killed. All three men love Tilo but she finally chooses Musa,with whom she shares concerns. When she cannot marry Musa she marries the journalist Nagaraj instead, only to leave him later because she feels stifled by his privileged family. The Bengali Biplab Dasgupta does not feature in her affections, but he is given a voice in a chapter where he gives us a description of her. This is apparently Roy seeing herself as she would like others to see her.

Tilo has a ‘small, fine-boned face’, ‘long thick hair, tangled and uncared for’ in which one might ‘imagine small birds nesting’ and ‘collarbones winging out from the base of her neck’; described later are her asymmetric mouth/ lips, something we see in pictures of Roy on the internet. Tilo is ‘enigmatic’ and we are told that that she lived in ‘a country of her own skin’, one that ‘issued no visas and seemed to have no consulates’. The last few words find correspondence in Roy’s announcement of her ‘secession from India’ after the nuclear tests of 1998: “If protesting against having a nuclear bomb implanted in my brain is anti-Hindu and anti-national, then I secede. I hereby declare myself an independent mobile republic.”

When Roy writes about Kashmir she writes unrelentingly about human rights abuses. As in her essays one cannot question many of her facts but the truths she offers are still partial ones. This stems from her too easily identifying some people as helpless victims and others as nasty oppressors. She has associated herself with Noam Chomsky but her writing has none of the insights Chomsky’s writing offers. As an instance of her oversimplifications Musa has a price on his head but we are told that he does not use the gun he carries; one wonders what use a militant who does not kill would be to his cause. Like most fictional victims of oppression and those who side with them Musa and Tilo are inevitably moral. One even suspects that Roy has Musa’s family killed off by the military so that Tilo’s relationship with him will be above board; better a dead family for Musa than have Roy’s alter-ego involved in a moral wrong with him!

Musa is unaffiliated to any group but such a position would be dangerous in Kashmir since there is a perpetual power struggle going on between the militant outfits; it is as though Musa were only characterized by his love for his people and ‘azadi’. After thus endorsing Musa’s sterling qualities, Roy has him (in turn) characterizing Tilo as someone prepared to sacrifice all for the wretched. In a circuitous way, therefore, much of the novel is devoted to Roy giving herself (as Tilo) a certificate. Its primary thrust is not onthe issuesit pretends to be about as much as on its author and her political genuineness.The one thing uniting the issues she brings together is that they all lead to her.

Arundhati Roy, regardless of the issues she takes up, is a writer and must be judged by her writing. I propose that for political essays to be useful they must bring independent perspectives to issues, those that enrich our understanding of situations. Politics is too complicated a realm for it to have only one meaning and it is necessary for the political essayist to add to public understanding - by reflecting and speculating upon political developments. The Kashmir imbroglio, for instance, cannot be understood simply as an innocent local populace fighting an occupation army. Roy rarely adds much of intellectual value to the most un-nuanced kind of political polemic and what she brings to each issue is not more than literary flair, often impressive but which frequently degenerates into juvenile invective and heavy sarcasm. Given the way she places herself at the centre of each issue, one could propose that she gains substantially more from the issues than they gain through her writing.

MK Raghavendra

Courtesy: https://www.google.co.in/

|