|

Introduction: Introduction:

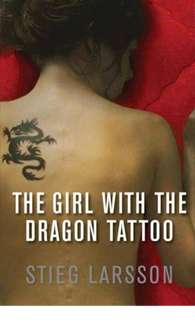

Stieg Larsson’s The Millennium Trilogy consisting of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo(published in Swedish as Men Who Hate Women in 2005 and translated into English in 2008), The Girl who Played with Fire (published in Swedish in 2006 and translated into English in 2009.), The Girl who kicked the Hornet’s Nest (published in Swedish as The Air Castle That Blew Up in 2007 and translated into English in 2009) deals with a new type of avenger figure whose emergence in popular fiction could be read as part of a broader pattern of representation of feminism within mass media and popular culture. The first novel of the trilogy revolves around the issue of the history of sexual abuse in Sweden as well as its contemporary face in the story of the protagonist. The main protagonist of the trilogy is Lisbeth Salander, a geek and a social outcast who has excellent skills in computer hacking and investigation. She works for Milton Security’s private investigation division. Mikael Blomkvist is a journalist for the political magazine Millennium. His love interest Erika Berger is also the editor in chief of the magazine. While trying to expose the businessman Wenner strom Mikael is convicted in court and anticipates three months in prison. It is at this point that his narrative converges with that of Lisbeth, as they both come together for investigating the history of the industrialist HenrikVanger’s family. In the ensuing investigation they discover the mysterious disappearance of Henrik’s niece Harriet Vanger in 1966. While Mikael takes up the job expecting vital information against Hans Erik Wennerstrom from Henrik Vanger, Lisbeth takes interest in the job because of her predisposition to expose a systematic killing of women. Mean while, owing to the illness of her legal guardian Holger Palmgren, a new guardian, Nils Bjurman, is appointed by the state. Bjurman turns out to be a misogynist and sexually abuses and rapes Lisbeth. In her spectacular retribution, Lisbeth brutally tortures Bjurman and records it on tape and threatens Bjurman not to report against her. The narrative of the novel oscillates between the story of Lisbeth’s personal life and the investigation of Vanger family history which exposes a legacy of sexual abuse and rape dating back to the days of Nazi Germany. In solving the case of Harriet Vanger’s disappearance it is revealed that Harriet’s brother Martin and her father Gottfried were habitual rapists who tortured and killed women. Towards the end of the novel Lisbeth rescues Mikael when he is abducted by Martin. She brutally beats up Martin and later while trying to flee from Lisbeth he dies in a car accident. Harriet Vanger is found and is reunited with Henrik, while Lisbeth provides critical information to Mikael regarding Wennerstrom which exposes the industrialist and restores Mikael’s lost reputation.

Critical Reception:

The publication of the trilogy saw immense public attention. In fact the first novel has already been adapted into a movie by Hollywood. It is noteworthy that a lot of the reviews and critical pieces immediately championed Lisbeth Salander as a feminist icon. Men Who Hate Women and Women who Kicks Their Asses: Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy in Feminist Perspective is an anthology of critical essays in which Kirsten de Welde in her essay titled “Kick-Ass Feminism” portrays Lisbeth as a feminist avenger and condemns Larsson for failing to pertain to the ideas of feminism in instances such as when Lisbeth opts for breast implants, or when she exhibits superhuman qualities in coming out of the grave. She identifies Salander as the primary physical feminist, which is not akin to being violent but which prescribes self-defence and physical prowess as means of regaining control from a male dominated society. 1 Judith Lorber in the essay “The Gender Ambiguity of Lisbeth Salander: Third-Wave Feminist Hero?” asserts that while Lisbeth doesn’t engage in feminist politics her defiance of patriarchal norms qualifies her as a feminist role model.2 The problem is that these critics misinterpret Lisbeth as feminist. Although Lisbeth does defy gender stereotyping, it can also be argued that Lisbeth’s stance as an avenger derives from her individual experience of suffering. She is in many ways not a feminist, rather a culturally constructed avenger figure. But it could also be argued that there is an attempt on the part of popular media to portray her as a feminist.

Sexual violence and female empowerment

Second wave feminists have suggested a relation between instances of sexual violence and a dormant desire to feel powerful. This desire often translates into instances of brutish beating and violently attacking the victims of sexual assault. In this context Stieg Larsson’s novel The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo could be seen as a reworked version of the rape-revenge narrative positioning the female avenger figure as a champion of feminist ideas. The representation of the female avenger figure in the novel is linked with the notion of female empowerment. I will argue that the representation and reception of the female avenger figure is part of a broader narrative of male fantasy. Although Stieg Larsson’s novel engages with the issue of violence against women, the avenger figure itself is a negation of the very feminist issues the novel professes to address. The problem lies not only in the manner of the representation of the avenger figure but also within the idea of violent retribution against sexual crimes.

Susan Brownmiller is one of the first feminists to explain sexual abuse as a means of control. Sexual violence therefore is more about domination and less of an expression of lust. Rape is used to keep women in a constant state of fear and trauma. “Women are trained to be rape victims”, 3 she observes in her seminal work Against Our Will. According to Brownmiller sexual coercion is less a sexual crime, and is actually part of a broader pattern of domination and control; that to keep women away from power- “All rape is an exercise in power, but some rapists have an edge that is more than physical. They operate within an institutionalized setting that works to their advantage and in which a victim has little chance to redress her grievance.”4 Therefore, it is clear that the system plays a vital role in marginalising rape victims and therefore in a way promotes victimhood. Sexual violence against women therefore, has to be understood in the context of violence emerging not from lust or sexual impulses but from a societal framework that aims to keep the status quo unchanged. This demands that victimhood should also ensure moral and physical weakness of the victim. Rape revenge narratives often use the trope of victimhood as a necessary prerequisite that paves the way for retribution. In this regard Stieg Larsson’s novel The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo uses the same trope of victimisation in setting up the rise of its avenger figure Lisbeth Salander. Larsson begins each section of the novel with statistical data which suggests the prevalence of sexual abuse against women in Swedish society as a common phenomenon. This also creates an atmosphere within the text whereby it is easy to locate women as victims:

“Eighteen percent of the women in Sweden have at one time been threatened by a man.” “Forty six percent of the women in Sweden have been subjected to violence by a man”. “Thirteen percent of the women in Sweden have been subjected to aggravated sexual assault outside of a sexual relationship.” “Ninety two percent of women in Sweden who have been subjected to sexual assault have not reported the most recent violent incident to the police.” 5 It is obvious from these statistics that Larsson’s narrative engages with the issues of sexual abuse of women in Sweden.

It is in the light of these issues that the female avenger figure is introduced as a socially ostracised introvert geek, who it is revealed later has a past history of abuse. Lisbeth work secretively for a security agency and earns her living through her computer hacking skills. She is tech savvy and pays no heed in maintaining socially accepted forms of behaviour. In other words Larsson positions his heroine within the non-normative. It is only after Lisbeth faces sexual abuse at the hands of her newly appointed legal guardian Nils Bjurman that we see her avenging nature come to the fore. Simultaneously the text also engages with the issue of a legacy of sexual violence in presenting the narrative of Harriet Vanger. In due course, Lisbeth herself gets involved in solving the disappearance of Harriet Vanger with the journalist Mikhael Bloomkvist.

Lisbeth’s status and popularity as an avenger figure is fuelled by her representation as an uncompromising and sexy avenger who kills men who hate women. Her textual representation in the novel actually caters to popular fantasies of female empowerment. Her avenging is largely interpreted as a new brand of feminism where women take back control of their life by violently fighting back. The violence with which Lisbeth exacts vengeance is sensational and outside the realm of legal course of actions. This is problematic because the text seems to advocate and subscribe to such forms of vigilante justice outside the legal framework. Sexual violence is a necessary pre-requirement for the avenging motif to come in within the narrative. Therefore, the avenging narrative often creates the legacy of sustained sexual violence against women. This in turn makes the trope of victimhood as a necessary requirement for the rise of the avenger figure. In this regard the novel creates a dystopian world within the narrative where women are subjected to gruesome forms of sexual violence. This world is a reflection of the actual scenario prevalent in Sweden. The trope of victimisation is therefore a narrative strategy whereby Lisbeth is first shown to be a victim of rape and only then she is transformed into an avenging figure. This narrative framework also serves to justify the violent avenging within the text- “an eye for an eye” should be the appropriate response to sexual violence as Eva Gabrielson says that Larsson believed. 6 Although the narrative does engages with issues of sexual violence, the representation of the female avenger figure sabotages any claim of the narrative being feminist in its intent. Rather, the avenger figure is represented in such a manner that reinforces patriarchal notions of imagined female empowerment and offers no real solution to the problem of sexual violence against women. In its representation of the female avenger figure, the narrative of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, first creates a legacy of sexual oppression and then uses the trope of victimhood to facilitate the rise of the avenger figure. This rise is shown as symptomatic of representing female empowerment. While depicting a sustained legacy of sexual abuse the narrative provides unverified data, in doing so the narrative clearly implicates sexual abuse of women to be a largely social phenomenon. In spite of this while representing female avenging the narrative foregrounds the rise of a singular avenging figure who works alone. There is no effort to represent female solidarity against oppression in community. The avenger figure fights alone and fights violently, creating the spectacle of rebellion and justice. Violent avenging and vigilante justice are shown to be the only plausible means to attain justice. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo represents this as a sort of empowerment. I argue that such an imagined empowerment is merely fantastical in nature and has no foundation in reality.

In this context it becomes clear that women like Lisbeth Salander are not an exception. In fact, Lisbeth is the product of this societal set up where the possibility of justice is slim. Lisbeth’s stance as an avenger figure could be understood in this context. The law of the land is no good for her. Although the laws against sexual crime exist, the system does not provide a credible basis for justice. Therefore, justice has to be done outside the law and through means of violence. This is exactly what Lisbeth opts for. The system fails her. It treats her as a retarded and weak person who should be protected. Rape is often a part of a broader pattern of violence against women. In the novel Lisbeth is often threatened by her state appointed guardian Nils Bjurman that she will not be provided any financial assistance if she refuses his demands for sexual gratification. This same man conspired to lock her up in a children’s psychiatric hospital when Lisbeth was 12 years old. Bjurman clearly enjoys the position of the custodian and derives sadistic pleasure in raping her. Bjurman’s role as a legal guardian adds to his sexual pleasure. In The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Bjurman says “She was going to have to be kept in check. She had to understand who was in charge.”7 (Larsson 124) And later he reiterates his power over her by stating “You are going to wind up eating this, you fucking cunt. Sooner or later I’m going to crush you.” (Larsson 134)8 This is not new for Lisbeth as throughout her life she has suffered in the hands of authority and the legal system. This constitutes her deep mistrust of the system. Lisbeth Salander fulfils the role of the ideal victim. Lisbeth Salander is a victim of stereotyping that labels her as weak, mentally retarded person with no sense of civility. She is an outcast, a misinformed geek whose life needs to be regulated and monitored by authority. She is considered an addict (Dr Teleborian reports her addiction to alcohol and drugs as pieces of evidence in her mental health report) set on the path of self -destruction. It is obvious that this type of stereotyping is problematic in the context of social justice for sexual abuse. Larsson’s narrative in the form of the Harriet Vanger murder case provides an insightful look in to the deep rooted sexism of the Swedish society dating back to the days of Nazi regime. This not only establishes a timeline of sexual crimes over a period of many decades but also establishes a continued legacy of victimhood. Martin Vanger‘s indoctrination in to the bloody practices of sexual abuse happened with the guidance of his father Gottfried. Larsson’s narrative unveils that it was Gottfried who taught Martin how to hate and manipulate women and treat them as objects. These lessons were combined with sessions of sexual abuse on Martin’s sister Harriet. Harriet Vanger could be seen as a similar figure to Lisbeth, although she is not an avenger, but she does opt to violently retaliate as does Lisbeth. Harriet fights back and kills her father. And this is where Martin takes over as the aggressor. Martin says: “We tried... to talk to her. Gottfried tried to teach her. We thought that she was one of us and that she would accept her duty, but she was just an ordinary...cunt.”9 .Clearly, Martin assumes that it the duty of her sister to be an object of sexual gratification for him and his father. But it is not only this assumption but there is also a deep rooted belief in the inferiority of the female sex that motivates the actions of Martin. He rapes and murder women. Harriet escapes her brother’s authoritarian persecution only by faking her death and disguising her identity. This is where she is different from Lisbeth, she continues to live with her victimhood by disguising her identity. Lisbeth on the other hand openly challenges such oppression. Martin and Gottfried Vanger as well as Bjurman all belong to the elite class of the society. They permeate and dominate the social set up within which the legal system functions. While Bjurman is a reputed lawyer, Martin is the captain of the one of the largest business houses of the country. It is obvious that in such a situation justice for Lisbeth or Harriet seems almost impossible. Susan Brownmiller in Against our Will says that “rapists may also operate within an emotional setting or within a dependant relationship that provides a hierarchical, authoritarian structure of its own that weakens a victim’s resistance...”10 . This is true for both Harriet and Lisbeth as they suffer abuse in the hands of the patriarchal father figure. The figure of the dominant oppressive male has shaped the character of Salander. In the third book of the trilogy her biological father Alexander Zalachenko tells her that her half-brother Niedermann should rape her because it might do her so good11 . According to ZalachenkoLisbeth is a worthless “dyke”. It is obvious that being the head of a crime syndicate Zalachenko is no different than Bjurman or Martin in his treatment of women. He is a man who repeatedly tortured his girlfriend and he insults Lisbeth’s mother as a “whore” who purposely got pregnant to trap him in to a relationship. It is in such a backdrop that Larsson shapes the character of Lisbeth and the millennium series offers an alternative path of vigilante justice. It is therefore imperative to note that the narrative of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, consciously creates a legacy of victimhood and it does so not only within the story of Lisbeth and Harriet, but also by providing statistical data. In doing so, the narrative likens Lisbeth and Harriet to the scores of women who are sexually violated in Sweden. Therefore, the narrative represents victimhood as a necessary precursor to the rise of the avenger figure- it is shown as a radical but logical defiance against large scale misogyny prevalent in Sweden. Victimhood sets the stage for Lisbeth to step in as the righteous avenger.

Avenging Motif: Violence and Vigilante Justice

Stieg Larsson’s Millenium trilogy became immensely popular as wildly enthusiastic reviews of the trilogy hailed it as a feminist achievement. Most of these reviews were basing their judgements on the amount of violence that the female avenger figure uses in order to dole out justice for the perpetrators of sexual abuse. Even in the Swedish and Hollywood cinematic adaptations, the violence of the avenger figure is represented as a marvellous feat orachievement. There is no doubt that violent retribution in the narrative plays an important part behind the popularity of the franchise. Larsson seems to be pointing to the idea that it is only through violent reaction that women can achievement true empowerment. KurdoBaksi observes in his book Stieg Larsson, My Friend that Larsson was one journalist who was quite aware of the dangerous situation of Sweden regarding issues of domestic abuse and racism and that the character of Lisbeth Salander was inspired by an actual rape scene that Larsson had witnessed and done nothing when he was only 15. 12 He further adds that “That was one of the worst memories Stieg told me about. It was obvious, looking at him, that the girl’s voice still echoed in his ears, even after he had written three novels about vulnerable, violated and raped women. Presumably it was not his intention to be forgiven after writing the books, but when you read them it is possible to detect the driving force behind them” 13 Baksi suggests that the women in his novels have minds of their own and go their own ways- “They fight! They resist! Just as he wished all women would do in the real world”14. This clearly throws some light on the idea that conceived the Millennium Trilogy. Larsson’s conception of the trilogy was aimed at representing the fighting back of women if we go by the words of Kurdo Baksi. Baksi further suggests that “If you are looking for a focus in Stieg’s writing, I would suggest it is the woman’s point of view. More or less everything he wrote depicts women being attacked for various reasons; women who are raped, women who are ill-treated and murdered because they challenge the patriarchy. It is this senseless violence that Stieg wanted to do something about and that he refused to accept.”15 But, if the Millennium trilogy caters to the visions of female empowerment, its conception of the very same is inherently flawed. Lisbeth’s avenging spirit could be read as an attempt to engage with issues of sexual violence in a manner that is uncommon and fantastical at the very outset. First of all, Lisbeth is represented as geek outcast, genius hacker, and introvert, and she is far from the likes of a common girl. This can be read as a conscious attempt to locate the figure of the female avenger in the realm of the extraordinary, as someone with whom any identification is impossible for the common women. Secondly, Lisbeth’s avenging is more of a solo individual act of vendetta, although she does collaborate with Blomkvist, her avenging is seen to reflect a tendency to act alone. This makes the avenging motif in the narrative as a singular tale of courage, heroism and vigilante justice. This marks an important facet of the avenging female figure as it locates the discourses of female empowerment outside the framework of community resistance and hence her vigilante status is championed as a mark of her unwavering strength and detective genius.

Judith Lorber describes Lisbeth Salander in her article titled “The Gender Ambiguity of Lisbeth Salander: Third-Wave Feminist Hero?”, as a person who “revels in sexual openness, outrageous gender self-presentations, and emotional coolness. But Salander never identifies as a feminist, nor does she use her (criminally acquired) wealth or her computer skills for any institutionalized activism. Third-wave feminists fight against restrictions on procreative choice and against racism, homophobia, and economic inequalities. By contrast, Salander’s personal, physical battle is against violent, sadistic men; her political battles, where she uses her investigative and hacking abilities, are against sex trafficking and international crime. She fights alone, mostly to defend herself or to get revenge on those who have harmed her. Once or twice, she fights for others (Erika Berger, when she is being cyber-stalked, and Mikael Blomkvist, to restore his journalistic reputation). But she belongs to no movement.”16

This clearly reflects the fact the Lisbeth, despite being an avenger figure is far from an actual feminist icon. She might seem to be so, but it is her vigilante status that renders her as a fantasy of female empowerment rather than actual empowerment. Like Lorber says, Lisbeth neither belongs to any feminist movement, nor does she strives to in the course of the narrative. Therefore, it has to be understood that it is her violent retribution that takes the centre stage in the narrative- it is what drives the popularity of the trilogy. The violence with which she avenges makes her a model of pleasure for the reader. This clearly undermines the feminist issues of sexual violence that the text engages with. The avenger figure is flawed in that she is represented in a manner that is suggestive of a male fantasy of female empowerment, and it is through her story that the fantasy of empowerment is actually played out. She is far from being a feminist herself. This clearly undermines the novel’s engagement with feminist concerns. Lisbeth uses violence to kill men who hate women, but this violence is in itself disempowering, because in her violent retribution she is less of a feminist icon, and more of a fantastical avenger figure whose actions make her a spectacle to be enjoyed. Judith Lorber aptly says: “The immediate response from feminists, young and old, is, “Right on, sister! You got those bastards!” But should we be celebrating the violence done by a woman when we deplore the horror of men’s violence? I think this “equal-opportunity” violence is the guilty secret of Larsson’s phenomenal success. We know it is fiction, so even if it isn’t properly feminist, we exult over Salander’s successful physical battles with men twice her size. It may be a vicarious purging of the constant threat of violence that women experience from men. Not only Salander, but Harriet Vanger and Erika Berger as well, are threatened with violation by fathers, brothers, and co-workers. By taking retaliation into their own hands (Harriet pushes her father into the river, Salander burns her father and drives Harriet’s sadistic brother to suicide, and a woman bodyguard captures Erika’s harasser), women bypass the male-dominated police and justice systems and protect themselves. The readers’ satisfaction with womanly justice trumps the violent means used.”17

The focus of the narrative seems to be on the violent retribution of Lisbeth and not on the way she is raped. Larsson is sparing in his description of Bjurman’s rape of Lisbeth, there seems to be a narrative gap as suggested by Marla Harris in her essay “Rape and the Avenging Female in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy and Hakkan Nesser’s Woman with Birthmark and The Inspector and Silence”.18 She says that the narrative gap could be seen from 8.30 on Friday night when she feels excruciating pain as Bjurman forced something up her anus to 4.30 on Saturday morning, when she was allowed to put on her clothes and go home. Marla suggests that the lack of detail here only intensifies the horror of the reader. She further adds that: “what, then, can we make of Larsson’s strategic abridgement? He is clearly less interested in titillating the reader by displaying Salander as passive and helpless than he is in representing her as empowered, guiding the reader to decipher the significance of small gestures and expressions, such as the look of ‘naked, smouldering hatred’ that Salander gives Bjurman as she leaves his flat, or even the significance of saying nothing.”19 Larsson’s focus, it seems was to represent the violence that Lisbeth exerts in her vengeance. The description of Lisbeth incapacitating Bjurman and then raping him is given in detail: “She worked steadily for two hours. When she was finished he had stopped whimpering. He seemed to be almost in a state of apathy.

She got down from the bed, cocked her head to one side, and regarded her handiwork with a critical eye. Her artistic talents were limited. The letters looked at best impressionistic. She had used red and blue ink. The message was written in caps over five lines that covered his belly, from his nipples to just above his genitals: I AM A SADISTIC PIG, A PERVERT, AND A RAPIST.”20

It is evident that such detailed description of the violence of avenging points to the fact that Larsson wanted his avenger to look like someone who can wrest back control and power. The whole trilogy is indeed an attempt to prove that women can also take back control, but only through means of violence. This is where Larsson’s avenger figure deviates from her feminist path of avenging sexual abuse. From the very outset of the narrative, she is motivated to react violently without opting for any legal course of action.

Therefore, Lisbeth’s brand of vigilante justice is something that is necessitated by the textual framework created by Larsson. Larsson seems to posit the fact that in such a dystopian society true justice can only be achieved through vigilantism. This clearly complicates the text’s claim to being sympathetic to the feminist cause. Feminist movements have always advocated legal as well as political reforms in tackling issues of sexual abuse. In presenting an avenger figure who champions the cause of vigilante justice the Millennium Trilogy seems to be totally negating any such possibility as a feasible solution to the issues of systematic violence against women.

Conclusion:

The spectacle of rape and its subsequent violent revenge in the text is widely assumed to be an instance of the triumph of feminism itself. In this regard vengeance becomes a kind of feminist enterprise. Feminism supported neither the concept of representing women as victims nor the issue of violent retribution. Rather, feminist ideology tended to alter and transform the orientation of the social discourses which marginalised women based on categories of gender and representation. These social discourses have always been bolstered by the system of patriarchy where social institutions have worked to keep the status quo of society unchanged. In fighting against such a system gender equality and justice have always been the prime concerns of any feminist agenda. The narrative of the novel revels in the representation of vigilante justice against the rapist and this in turn completely undermines its assumed feminist stance. The narrative first sets up the act of sexual violence so that the act of revenge against the perpetrator could provide a sort of fantasy for the reader. The notion of vigilante justice serves as a popular fantasy of female empowerment. In this context it can be argued that the first act of sexual violence actually provides motivational logic for the ensuing avenging.Authentic feminism can be seen as a moral position since it seeks to empower by bringing into light the position of those disempowered by the system of patriarchy. However, gloating over vigilante justice against perpetrators of sexual abuse cannot be deemed as a feminist attitude. The novel therefore fails to justify its presumed feminist stance. The female avenger figure is not emblematic of female empowerment but, rather, a symptom of feminine disempowerment since it presumes institutionalised injustice towards women in society, for which personal acts of vengeful violence are deemed compensation.

Notes/references:

| 1. |

Welde, Kirsten de.‘Kick-Ass Feminism ’From Donna King and Carrie Lee Smith (eds). Men Who Hate Women and Women who Kicks Their Asses: Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy in Feminist Perspective, Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2012.

|

| 2. |

|

| 3. |

Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New York: Fawcett Books, 1993 p 309.

|

| 4. |

Ibid,p 256.

|

| 5. |

Larsson, Stieg.The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Trans. Reg Keeland. London: Mac Lehose Press, 2011.

|

| 6. |

|

| 7. |

Larsson, Stieg. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Trans. Reg Keeland. London: Mac Lehose Press, 2011, p124.

|

| 8. |

Ibid, p134.

|

| 9. |

Ibid, p302.

|

| 10. |

Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New York: Fawcett Books, 1993, p 256.

|

| 11. |

Larsson, Stieg. The Girl who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest.Trans. RegKeeland London: Mac Lehose Press, 2009, p 200.

|

| 12. |

Kurdo Baksi, Steig Larsson, My Friend. Trans. Laurie Thompson London, Mac Lehose Press, 2010, p 118.

|

| 13. |

Ibid p119.

|

| 14. |

Ibid

|

| 15. |

Ibid.

|

| 16. |

|

| 17. |

Ibid.

|

| 18. |

Harris, Marla,‘Rape and the Avenging Female in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy and Hakkan Nesser’s Woman with Birthmark and The Inspector and Silence’ from Astrom, Berit, Katarina Gregersdotter, and Tanya Horeck (eds.)Rape in Stieg Larsson's Millennium Trilogy and Beyond: Contemporary Scandinavian and Anglophone Crime Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, p 67.

|

| 19. |

Ibidp 69.

|

| 20. |

Larsson, Stieg, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Trans. Reg Keeland. London: Mac Lehose Press, 2011, p 145.

|

Arijit Saha is a research scholar in the Department of English, Visva-Bharati. His field of research include feminism, popular culture and the representation of female figures in films, graphic novels and videos games.

|

|