|

|

|

|

The Nation and the Liberal Polemicist examines the writing of India's liberal polemicists on the Mumbai terror attacks.

Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IPL, 20-20 Cricket and Audience Manipulation

tries to find logic in the aesthete's view that places 20-20 cricket much lower than traditional test cricket.

Read Read

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

See the contents page

Go Go |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Home > Usha KR |

|

Two Destinies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

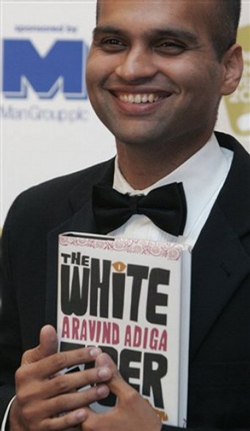

Review of The White Tiger, Aravind Adiga, HarperCollins, 2008, pp 321, Price: Rs 395/-

Usha KR

Arvind Adiga's 2008 Booker-winning novel, 'The White Tiger', is set in a very familiar milieu - the India that comes to us through the daily newspapers, that screams at us from the headlines every day, a country that 'has no drinking water, electricity, sewage system, public transportation, sense of hygiene, discipline, courtesy, or punctuality', which, further, is venal to the core, where 'there are just two castes: Men with Big Bellies, and Men with Small Bellies. And two destinies: eat - or get eaten up.' And two places - Darkness and Light.

The story of Balram Halwai is set in the area of darkness, specifically in the pitch black village of Laxmangarh in Gaya district of Bihar, a stone's throw from the Bodhi Tree under which the Buddha obtained enlightenment. Balram's father is an impoverished rickshaw puller in Laxmangarh, which is in the vice-like grip of the most avaricious landlords - what little the landlords leave for Balram's father (and the others in the village) is immediately snatched away by the women of his household. Balram is a bright boy who shines in his shadow-of-a-school (where there are no teachers and the funds allotted for basic equipment like desks and chairs and blackboards are swallowed by the authorities); a visiting inspector who identifies him as a 'white tiger', that rarest of rare beasts that comes along once in a lifetime in the commonplace jungle, promises him a scholarship but it comes to nought when Balram is Aravind Adiga pulled out of school and set to work in a tea shop to pay off the accumulated debts of his family. Balram then quickly abandons all sensitivity, works with his wits, tramples over the other contenders and soon manages to become a driver cum man-of-all-work in the house of one of the Laxmangarh landlords in Delhi. Not surprisingly, the reigning deity of Laxmangarh is Hanuman, the perfect devotee, the perfect servant. Balram does his best to emulate such perfection of servitude and his 'master' is a man with a conscience (he has only just returned from the US where he was educated and where he lived for long) but the man lacks the will to contend with a corrupt system and in the final count his loyalties lie with his class and his family. He uses Balram remorselessly, even making him take the rap when his wife runs over a child living on the streets - in the event Balram does not have to make good as no formal complaint is registered. The mean streets of Delhi and the ways of his master give Balram the education he was denied in school and he turns out to be a perfect student. One day, as he is driving on the road, he stops the car, clubs his master to death, steals the bag of cash that he was taking to bribe a minister, escapes to Bangalore and sets up as an entrepreneur in the outsourcing industry, using the very same venal and brutal means that had been used against him, to become successful. The story of Balram Halwai is set in the area of darkness, specifically in the pitch black village of Laxmangarh in Gaya district of Bihar, a stone's throw from the Bodhi Tree under which the Buddha obtained enlightenment. Balram's father is an impoverished rickshaw puller in Laxmangarh, which is in the vice-like grip of the most avaricious landlords - what little the landlords leave for Balram's father (and the others in the village) is immediately snatched away by the women of his household. Balram is a bright boy who shines in his shadow-of-a-school (where there are no teachers and the funds allotted for basic equipment like desks and chairs and blackboards are swallowed by the authorities); a visiting inspector who identifies him as a 'white tiger', that rarest of rare beasts that comes along once in a lifetime in the commonplace jungle, promises him a scholarship but it comes to nought when Balram is Aravind Adiga pulled out of school and set to work in a tea shop to pay off the accumulated debts of his family. Balram then quickly abandons all sensitivity, works with his wits, tramples over the other contenders and soon manages to become a driver cum man-of-all-work in the house of one of the Laxmangarh landlords in Delhi. Not surprisingly, the reigning deity of Laxmangarh is Hanuman, the perfect devotee, the perfect servant. Balram does his best to emulate such perfection of servitude and his 'master' is a man with a conscience (he has only just returned from the US where he was educated and where he lived for long) but the man lacks the will to contend with a corrupt system and in the final count his loyalties lie with his class and his family. He uses Balram remorselessly, even making him take the rap when his wife runs over a child living on the streets - in the event Balram does not have to make good as no formal complaint is registered. The mean streets of Delhi and the ways of his master give Balram the education he was denied in school and he turns out to be a perfect student. One day, as he is driving on the road, he stops the car, clubs his master to death, steals the bag of cash that he was taking to bribe a minister, escapes to Bangalore and sets up as an entrepreneur in the outsourcing industry, using the very same venal and brutal means that had been used against him, to become successful.

This is Adiga's first novel and to his credit, it is a self-assured debut. Once the monotone of the novel is registered, it is consistent, the plot is structured tightly and moves smoothly: the author does not aspire to novelty or unconventionality in form, structure or theme (which is not necessarily desirable), nor idiosyncrasies in character but uses conventional devices without fault almost.

However, at some point in this novel, even as page follows page effortlessly, the questions that become obvious are: to whom is this story addressed and how is it told? To take up the second question first, Adiga structures the novel as a series of letters to the Chinese premier, who is about to visit Bangalore, in an effort to tell him the 'truth' about Bangalore and disabuse him of the widely held notions about Bangalore's success as the nation's IT hub. This is a distancing device used deliberately by the author in a novel written in the first person, purportedly by the illiterate Balram who has little knowledge of the world outside Laxmangarh - Balram's tone is consistent but he is very obviously ventriloquising for the author who is refracting Balram's sensibility through his own lens. This in itself is perfectly plausible but Adiga paints his canvas with very broad brush strokes, his satire though incisive is heavy and relentless, it leads him to essentialise characters and situations till every nuance is beaten out. In fact, his master vs servant position is strongly reminiscent of the Manichean Hindi film formulations of rich vs poor, landlord vs tenant and black evil vs white good.

To illustrate, is a passage from the 'naming ceremony', when Munna becomes Balram.

| |

See, my first day in school, the teacher made all the boys line up

and come to his desk so he could put our names down in his

register. When I told him what my name was, he gaped at me.

'Munna? That's not a real name.'

He was right; it just means 'boy'.

'That's all I've got, sir,' I said.

It was true. I'd never been given a name.

'Didn't your mother name you?'

'She's very ill, sir. She lies in bed and spews blood. She's got no time to name me.'

'And your father?'

'He's a rickshaw-puller, sir. He's got no time to name me.'

'Don't you have a granny? Aunts? Uncles?'

'They've got no time either.'

The teacher turned aside and spat - a jet of red paan splashed the ground of the classroom. He licked his lips. |

Another, where he sums up the spirit of Bangalore:

| |

I tried to hear Bangalore’s voice, just as I had heard Delhi’s.

I went down M.G. Road and sat down at the café Coffee Day, the one with the outdoor tables. I had a pen and a piece of paper with me, and I wrote down everything I overheard.

I completed that computer program in two and a half minutes.

An American today offered me four hundred thousand dollars for my start-up and I told him, ‘That’s not enough!’

Is Hewlett-Packard a better company than IBM?

Everything in the city, it seemed, came down to one thing.

Outsourcing. Which meant doing things in India for Americans over the phone. Everything flowed from it – real estate, wealth, power, sex. So I would have to join this outsourcing thing, one way or the other. |

To whom is Adiga addressing this unleavened story, in his faultless prose? Any Indian who reads the newspaper knows that India isn't shining and that our post-liberalisation growth rates apply only to part of the economy. We know that the ship is floundering with 400 billion poor clinging to its sides. (And speaking of current news stories, no fiction can match the callousness of our society and the police than the horrific Nithari killings or the (unsolved) Arushi murder, both of which also have a master-servant twist that would stretch any fictional imagination.) Is this all there is to this much celebrated book, one wonders. A broadly fictionalized account of the everyman Indian, told in just one colour - black, with no shades of grey even to relieve it; a story that Bollywood has brought to us in the infinite variations of Eastmancolour, immortlised by Amitabh Bachchan's many-times-over Vijay, in the 70s and 80s. It is not just that we know the tale, we are also familiar with fictional renditions of it in different media.

However, about two thirds through the book, Adiga manages to pull it off by a slim thread, perhaps without his own knowledge; he uplifts the book from a satire on the state of things as they are into a dirge for the nation; he transmutes it into a work of fiction led by an individual voice. Despite the battering ram of gory realism and unremitting satire, the narrative acquires a hallucinatory quality, as if Adiga recognizes that the story must be transmuted by a literary device. Balram is greeted by the water buffalo - beloved of the women in his family, who would feed the animal before feeding Balram's father, the tired bread winner of the family - carting a load of dead buffalo skulls, which turn miraculously into the faces of his family and call out to him. Earlier in the novel, Adiga makes room for this. For Balram is denied the traditional source of succour that is available to the everyman Indian - a supportive family, especially the women. Balram's grandmother and aunts are every bit as greedy and grasping as everyone else (Adiga dispenses with Balram's mother very early, and his father soon after - thus relieving Balram of any ties of true affection, of a conscience and the only genuine moral dilemma he might have had) and Balram condemns them all to a brutal death at the hands of the landlords whose brother he has murdered.

Earlier in the novel too Adiga sets out the promise of the 'white tiger' and makes good in perhaps the most under-written and effective scene in the novel. Before making his escape to Bangalore, Balram and his nephew visit the Delhi zoo and he comes face to face with the white tiger at last. As Balram's eyes meet those of the white tiger, that grand, majestic creature, king of the jungle, born but once in a generation, caged now behind bamboo bars, the tiger disappears and Balram falls into a dead faint. Balram Halwai, Adiga suggests, is not just the poor boy who has defied his destiny, the everyman Indian whose fantasies have turned to reality, a murderous criminal who becomes a beacon of society, but a self-fulfilling prophecy, a literary instrument wielded deliberately by the author. He is the white tiger, simultaneously the king of the jungle, born but once in a generation and a freak of nature, result of a pigment malfunction, symbol of stunted potential and arrested development. When he comes face to face with himself, it seems wholly appropriate that the mirage must disappear and that the flesh-and-blood Balram be rendered senseless on recognizing the enormity of the moment of truth.

Balram's motive for killing his employer (who, by Balram's own admission is not a bad man) is never convincing enough (perhaps this is because the motivation for the act lies in the setting, in the milieu and does not transcend successfully into the voice and acts of the individual character), we do not feel his rage, only its justification by the author. Yet, we do not look for retribution to fall upon Balram, but see him instead as an instrument of justice, however convoluted - this is again to the writer's credit. The transformation from Munna to Balram Halwai to Ashok Sharma - upper class, upper caste entrepreneur is complete. But he cannot rest in peace, he is but a creature with a flawed destiny, the white tiger. All of his family is destroyed but one - a nephew whom Balram cannot bring himself to kill, but brings with him instead to Bangalore, and who will be both his heir and his nemesis. In this story of unrelenting darkness, it appears as if Adiga cannot help scripting a moral ending.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Usha KR is an editor of Phalanx |

|

| Top |

|

|

|

|