|

Few would doubt the fact that the Sangh Parivar has had a momentous historical presence in Indian politics and public life in the twentieth century. This is particularly true of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its leadership. The RSS has been the parent body for most of the Parivar organizations like the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the erstwhile Jana Sangh and the Vishwa Hindu Parishat (VHP), and various other groups like Swadeshi Jagaran Manch, Saraswati Shishu Mandir, Bharatiya Kisan Sangh, Seva Bharti, Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, Bharatiya Vichara Kendra, Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram and so on. The cadre in many of these organizations is drawn from the RSS. Although the RSS has consistently stayed away from active participation in electoral politics, it has remained the ideational mentor of all organizations and has appeared on the scene more than once to resolve crises when the BJP faced internal trouble and dissent. No credible estimates of the membership of the Parivar exists, but it is likely to be anywhere above six million, with the RSS and its women’s wing alone consisting of four million fulltime members.(1) Yet, it is surprising that there is hardly any compelling scholarly account of the making of the Parivar, despite tons of literature produced every year.(2) Among the academically oriented writings, some are often nothing more than poorly documented diatribes against the politics the Parivar stands for.(3) They are methodologically questionable and also hyper-functionalist in their approach to the problem, apart from being instrumentalist and opportunistic in their reasoning.(4) It is not uncommon in these works to brand the Parivar fascist.(5) These works command admiration only from a small section of readers, and this is due in large to their commitment to progressive, secular, emancipative politics. But political commitment is a small pretext for poor assessment of a contemporary historical phenomenon, even if the said phenomenon is antithetical to one’s own brand of politics.

|

Most researches on the Sangh Parivar are not sensitive (or are perhaps insensitive) to the fact that the men and women who make up the Parivar share a set of ethos and visions about the self, the nation and the right life, which are organized around a mono-causally structured narrative of history. Paradoxically enough, such shared values tend to be cause for internal conflicts, especially when it comes to the question of how these values are expected to inform future programmes and initiatives. The internal conflicts of the Parivar are rarely acknowledged in these researches.(6) We are repeatedly told that the RSS, and its allies and affiliates, have always displayed exceptional unity in their thoughts, programmes and action. If this is true, the Parivar must be regarded an anthropological wonder, for history knows of no human collective that is perennially united and devoid of conflict.(7) |

If the Parivar has survived for close to a century against severe odds, its ethos, visions and narratives of history cannot simply be written off as idiosyncratic fantasies meant to secure political mileage. They are of course governed by a false consciousness of history and its teleology. But they are nonetheless powerful products of a historically produced mentality with its own convictions and certitudes. They look like instrumentalist caprices only when one expects the ideas informing their praxes to be rationally constituted. The Parivar’s ethos, visions and narratives of history are fraught with logical and empirical inconsistencies, and are not in harmony with the secular democratic worldview. Expecting a historical phenomenon to pass the muster of such a worldview is perhaps one of the most unhistorical directions that academic research can take. But the Parivar does not represent a distinct phase in the history of thought or ideas; the Parivar is not an intellectual movement. Rather, it exemplifies an entrenched mentality which has a history of its own.

|

This paper examines the nature of the mentality that found expression in Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar’s We or Our Nationhood Defined and Bunch of Thoughts, two of the foundational texts of the RSS. Our discussion presents only one among the many

dimension of the Hindu nationalist mentality, and does not exhaust its polyphonic nature. The fact needs to be borne in mind that the multiple dimensions of this mentality are not in a uniform state of harmony; they betray tendencies crisscrossing one another in complimentary, conciliatory and conflict ridden terms from time to time.(8) The mentality figuring in Golwalkar’s works does not represent all shades of the Parivar mentality. It is only one of its many voices, perhaps a dominant one.

Our use of ‘mentality’ as a category is inspired by the French Annales School’s ‘history of mentalities’,(9) but my treatment of the notion departs from it. In my understanding, ‘mentality’ is a four-fold phenomenon: |

i) it is an explicit description and/or an implicit understanding of the world; ii) it describes or understands the world in the existing form as well as in prospective, programmatic terms; iii) this description or understanding of the world, although ideational, is not rationally constituted; and iv) it is governed by the false consciousness of time, space, causality and historical teleology, and is hence, ideologically determined.(10) By its very definition therefore, a mentality is not open to critique on the grounds that it is rationally wanting or historically inaccurate.

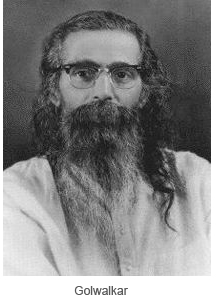

Golwalkar (1906-1973), who succeeded Keshav Baliram Hedgewar as the second sarsanghchalak (chief) of the RSS, published We or Our Nationhood Defined in 1939. This is the only book he wrote. Bunch of Thoughts and the other works appearing in his name are collections of essays and speeches delivered by him on various occasions. Early in his career, Golwalkar studied zoology at the Banaras Hindu University. Between 1930 and 1933, he taught there after discontinuing a doctoral programme at the Marine Aquarium in Madras. He then obtained a degree in law, was introduced to Hedgewar, and spent a few months at the Ramakrishna Mission’s Sargacchi Ashram in Bengal where he was initiated by Swami Akhandananda. Golwalkar left the Ashram and became a fulltime member of the RSS in 1937 after the demise of Akhandananda. He rose to the position of sarkaryavah (general secretary) of the RSS within two years. Hedgewar passed away on 21 June 1940, nominating Golwalkar as his successor. Golwalkar held this position till his death in 1973.

|

We or Our Nationhood Defined was widely read for several years in the Parivar circles before being formally withdrawn from circulation. It is believed that the book had a profound impact on the RSS, and was accepted as its Bible.(11) Even if this is not entirely true, we may still surmise that an emergent Hindu nationalist mentality found expression in We or Our Nationhood Defined and the other works of Golwalkar’s which became a point of reference.

We or Our Nationhood Defined is an attempt to arrive at a definition of the nation, and test it against the Indian situation. On more than one occasion Golwalkar tells us that his is a scientific understanding of nationhood.(12) The broader conceptual apparatus of his text is informed by a thesis of fundamental historico-normative difference.(13) The basis for this difference is not elaborated in We or Our Nationhood Defined. Golwalkar spells it out briefly in ontological terms in an essay in the Bunch of Thoughts. |

According to our philosophy, the very projection of the Universe is due to a disturbance in the equilibrium of its three attributes – sattva, rajas and tamas – and if there is a ‘gunasamya’, perfect balance of the three attributes, then the Universe will dissolve back to the Unmanifest State. Thus, disparity is an indivisible part of nature and we have to live with it.(14)

The three gunas are in a state of flux and vary from time to time. Therefore, the nature of difference is also capable of undergoing qualitative changes across time. The crux of the matter, though, is the implicit claim that the existence of the universe in a manifest form is itself contingent on difference; the human world, therefore, cannot be otherwise.

The above thesis occurs in a critique of democracy and communism. In Golwalkar’s understanding, democracy and communism are not ideals or goal-oriented political praxes, but merely specific forms of statecraft. And the state is an institution he is deeply skeptical of; the same skepticism naturally extends to democracy and communism. In We or Our Nationhood Defined, Golwalkar identifies the state as a “hap-hazard bundle of political rights.”(15) At the same time, he makes a distinction between the

nation and the state.(16) “Do we clearly perceive that the two concepts — the nation and the state — are distinctly different? If we do not, we are merely groping in the dark.”(17)

|

In the scheme of things that We or Our Nationhood Defined represents, the nation is the basic legitimate unit into which human collectives are expected to organize themselves.(18) Thus, we may infer that the thesis of difference based on the disequilibrium of gunas does not extend to the nation because it is a single unit. For the same reason, the nation cannot be allowed to undergo fissures or fractures of any kind. But Golwalkar recognizes that fragmentation of the nation is not merely a potential possibility but a contingent reality as well, as it is made up of individuals who are by nature prone to greed, selfishness and other vices.

The existence of lesser collectives like linguistic groups are |

problematic and do not evoke sympathy in Golwalkar’s workings. But the same is not true of caste. Caste system is seen as functionally significant for the nation. They enable the division of labour among the people.

If a Brahmana became great by imparting knowledge, a Kshatriya was hailed as equally great for destroying the enemy. No less important was the Vaishya who fed and sustained society through agriculture and trade or the Shudra who served society through his art and craft. Together and by their mutual interdependence in a spirit of identity, they constituted the social order.(19)

Golwalkar does not consider the existence of divisions as problematic. For him, this “functional” division is not an impediment to the national consciousness. It is also an essential feature of the nation; “the so-called casteless societies crumbled to dust never to rise again” while “the so-called ‘caste-ridden’ Hindu Society has remained undying and unconquerable and still has the vitality to produce a Ramakrishna, a Vivekananda, a Tilak and a Gandhi.”(20) Golwalkar goes on to note that

Persons interested in calumniating Hindus, make much of the caste system, the “superstitions”, the want of literacy, the position of women in the social structure, and all sorts of true or untrue flaws in the Hindu Cultural Organisation, and point out that the weakness of the Hindus lies solely in these…. Look at the times of the Mahabharat, of Harshwardhan, of Pulakeshi, all the so called evils of caste etc. were there no less marked than today and yet we were a victorious glorious nation then. Were not the bonds of caste, illiteracy etc. at least as stringent as now, when the country witnessed the grand upheaval of the Hindu Nation under Shiwaji? No, it is not these that are our bane, but the dormancy of National feeling, which alone by fostering petty ambitions, created internal dissentions and facilitated foreign invasions.”(21)

What is true of castes is nonetheless not true of the individual. Castes, whether or not prone to corruption, do not affect the unity of the nation, but in the absence of the national consciousness, the nation is likely to be betrayed by corrupt individuals, a danger never perceived in the case of castes. The dormancy of Hindu nationalist consciousness “produced mean selfishness, suppressing noble patriotism and gave birth to the whole race of Jaychand Rathod, Manshing, Chandrarao Morey, Sumersingh and their worthy progeny of the day, best unnamed.”(22) There is therefore no room for the individual in Golwalkar’s nationalism while parochial tendency of caste are accommodated. The individual on the other hand is shorn of selfhoods, agency and autonomy. The only rightful way of individual self-expression is to embrace the Hindu national identity and dissolve one’s individuality into it.(23) This view of Golwalkar’s found many admirers within the Parivar. But it has also been cause for much bitterness, for a number of individuals within the Parivar believed in action and individual self-expression.(24)

The erasure of the individual prevents the possibility of any individual from being worshipped. Hero worship or the cult of personality is therefore out of question in this framework of things. Golwalkar never makes a call for worshipping Shivaji, Rana Pratap, Ramakrishna or Vivekananda, whose names are repeatedly invoked in the superlative. These men are expected only to be exemplars of the Hindu national consciousness. Neither does Golwalkar advocate the worship of deities like Rama, Krishna or Shiva and goddesses like Lakshmi, Durga and Parvati. The object of his worship is Bharatmata, an abstract personification of India. This position clearly brings the RSS into conflict with the Rashtra Sevika Samiti, which upholds the worship of the goddess in her form as Durga, Parvati, Kali, and Ashtabhuja who embodies Mahalakshmi, Mahasarasvati and Mahakali.(25) Two months before his death, Golwalkar reiterated his position on hero worship when he wrote to the RSS asking it not to build a memorial for him.(26)

The RSS moved away from this ideal in a big way from the late 1970s and the early 1980s, advocating the worship of Rama, and organizing the birth centenaries of Hedgewar (1989) and Golwalkar (2006) on a massive scale. The cult of personality has since been an important constituent of the RSS. We can trace this development to the rise of a new sense of masculinity in the aftermath of the great emasculation of Indian manhood during the Emergency, but that is another story.

One of the foundational assumptions in We or Our Nationhood Defined and Bunch of Thoughts is that the human agency has no role to play in the emergence of nationhood. This idea issues directly from a mentality that promotes the erasure of the individual. Nations, according to We or Our Nationhood Defined, are products of an evolutionary process.

If we take into consideration the fact that the Mahabharat depicts a highly organised, elaborate, civilized society, at the zenith of its power and glory, and try to find out how long the race must have taken to attain that stage, we shall certainly have to go back another several thousand years into the unknown past. For such a complex civilisation could not have been the product of a day.(27)

Human initiative cannot therefore be part of the foundations of a nation, as nations can come into being only through “several thousand years” of evolution.

The nation is made up of five essential unities, viz. geographical, racial, religious, cultural and linguistic.(28) We or Our Nationhood Defined is primarily an attempt to unpack this definition. Golwalkar cites the works of Fowler, Hole-Combe [sic], Burgess, Bluntsley [sic], Getel [sic] and Gumplovicz [sic] from the West and Kale from India in developing his definition of the nation.(29) The five unities, says Golwalkar, were recognized as constituents of the nation even in India several thousand years ago. According to him, desha corresponds to territory and jati, to race.(30) The other three components are not independently mentioned, but they are embodied in the concept of janapada,(31) “there being no differences on the score of Religion, Culture or Language.”(32) The nation thus becomes a “universal concept”(33) transcending the boundaries of the East and the West. Does not the Hindu nation, then, represent the flowering of a universal truth?

None of the five essential unities are recognized as products of human volition. Human beings are bearers of what exists or evolves independently of conscious human endeavour. In other words, the national consciousness which people carry is a consciousness about their role as bearers of something which is humanly impossible to bring into existence. To be a true Hindu nationalist then calls for a considerable measure of inner strength and determination, or what Golwalkar calls race-spirit.(34)

This, although tacitly, is a celebration of the individual; it quietly underscores the might and grandeur of the individual in forming a collective in order to inherit the nation, possess it, and bequeath it to posterity. This—the affirmation of the individual through the erasure of the individual—is the internal dialectic of the mentality which tries to functionally obliterate the conflict between the individual and the collective. This is what makes the avowed silencing of the individual an effect of ideology (false-consciousness). A great amount of conflict within the Parivar springs from this unresolved dialectic of individual volition being implicitly treasured but explicitly held in check. The resolution Golwalkar proposes is romantic and metaphorical. The erasure of the individual is according to him the erasure of only its form. The content or the spirit persists and informs the nation. Golwalkar likens the erasure of individuality to a piece of salt dissolving in water.(35) The salt has ceased to exist physically, but its taste remains. The individual is the ‘taste’ of the nation.

If the fascination for the nation calls for sacrifice of one’s individuality and does not promise anything palpable by way of gratification, the nation must obviously be a false consciousness representing the reified manifestation of a deeper reality. What is this reality? We can decode this from the idiom Golwalkar uses in We or Our Nationhood Defined. Consider the following lines.

Invidiously the Hindu Religion and Culture are calumniated, Hindus taught to discard as old-fashioned and out of date their noble heritage, and what is worst, their history is distorted and thus they are educated to believe that they never were a Nation, they were no children of the soil, but mere upstarts, having no better right than the Moslems or the British to live in the country, they never were masters of the country but were always, either of the Moghuls or of the British—meek drawers of water and hewers of wood.(36)

Here, such contradictory expressions as ‘children of the soil’ and ‘masters of the country’ imply an intimate relationship of possession. The Hindu possesses this land by way of exercising collective and absolute control over it. No individual or group other than the Hindu—identified as a collective—can lay claims to this land. Golwalkar criticizes “the amazing theory…that the Nation is composed of all those who, for one reason or the other happen to live at the time in the country.”(37) This “serai theory” of anyone claiming

stakes in India merely by virtue of having physically arrived here is “antinational and denationalizing.”(38)

Among the many provocations which led to the writing of We or Our Nationhood Defined was the Aryan invasion theory. This theory had the effect of invalidating the Hindu’s natural claims over the territory and opening up such claims to all immigrants, including the Muslims and the British. Writes Golwalkar,

And after all what authority is there to prove our immigrant nature? The shady testimony of Western scholars? Well, it must not be ignored that the superiority complex of the “White Man” blurs their vision. Can they acknowledge the greater antiquity and superiority of a nation, now held in thrall by one of their peoples? They have neither such generosity nor love of truth. Till yesterday they wandered wild in the wildernesses, their nude bodies weirdly tatooed (sic) and painted. They must needs show, therefore, that all peoples of the world were at that time in the same or worse state. And they set about proving, when the superior intellectual and spiritual fruits of Hindu Culture could not be denied, that, in origin, there was but one Aryan race somewhere, which migrated and peopled Europe, Persia and Hindusthan, but that the European stock went on progressing whilst the Hindu branch mixed with the aborigines, lost its purity and became degenerate. Again there is another consideration. By showing that the Hindus are mere upstarts and squatters on the land (as they themselves are in America, Australia and other places!) they can set up their own claim. For then neither the Hindus nor the Europeans are indigenous and as to who should possess this land, becomes merely a matter of superior might, mere priority of trespass giving no better right to any race to rule undisturbed on any part of the globe.(39)

In Golwalkar’s narrative “we—Hindus—have been in undisputed and undisturbed possession of this land for over 8 or even 10 thousand years before the land was invaded by any foreign race.”(40) The allure for nationhood, then, derives from a natural and ageless right to possess the land. Note that the land is possessed by the Hindus and not owned by an individual or group. “What we want is swaraj; and we must be definite what this “swa” means.”(41) Nation, as it emerges here, is the reified visage of landed property. Access to this property is generalized, as possession is not substantial but unfolds at the ideational level in the form of a national consciousness. The existence of this reified entity depends on its representation in sublime and romantic terms:

a culture of such sublime nobility that foreign travellers to the land were dumbfounded to see it, a culture which made every individual a noble specimen of humanity, truth and generosity, under the divine influence of which, not one of the hundreds of millions of the people, ever told a lie or stole or indulged in any moral aberration.(42)

The nation is thus an object of desire, representing “the awakening of a longing for possession, of the mild and warming fantasy of landed property,” as Fredric Jameson has in another context put it.(43) This ideology animates the longing for nationhood which governs the Hindu nationalist mentality. The longing is forcefully articulated in the Bunch of Thoughts.

Only in the soil of Bharat have the Hindus pinned their sentiments of dharma. The appeal of the holy places takes him round the entire Bharat, and Bharat only. His material interests also are embedded in Bharat only. As such, this devotion is wholly and solely to Bharat. Hence there can never be any conflict in his mind between Swadharma and Swadesh.(44)

The desire for landed retreat is not spelt out in the language of consumption or in libidinal terms. The nation is not expected to be a Bhogabhoomi, but a Dharmabhoomi, Karmabhoomi and Punyabhoomi,(45) as well as a Tapobhoomi(46) and Mokshabhoomi.(47) What this entails is not the immediacy of gratification or the anxieties of discontentment, but the timelessness of possession and the deliverance it promises. The longing is for “such a land with divinity ingrained in every speck of its dust.”(48) In positing the nation as an expression of the eternal, pure, divine truth, Golwalkar forecloses the possibility of pleasure or bhoga making inroads into the desire for the nation and rendering possession temporally finite. The fulfillment of possession and not the gratification of consumption is what makes reification in the case of the nation so compelling. The longing for landed retreat is internalized into an ideational reality; it ceases to be an external, physically owned entity.

That the nation is the most basic legitimate unit of human organization and that nations differ from one another have serious implications, when examined against the three gunas theory. The diversity of the universe, as we have seen above, is the result of an imbalance in the three gunas. The relative positions of the gunas are never stable. They exist in a constant state of friction. When transposed to the level of nations, it implies that nations are in a constant state of conflict with one another. They do no flower into fulfillment in times of peace. Lasting peace is antithetical to the fortunes of a nation. This is what happened to India after the battle of Mahabharata.

In the long peace which succeeded the great battle of the Mahabahrat, the whole nation was lulled into a sort of stupor, and the cohesive impulse, resulting from a knowledge of impending common danger, having ceased to function for centuries, for want of such danger, a gradual though imperceptible, falling away from a living consciousness of the one Hindu Nation, resulted in creating little independent principalities and weakened the Nation. Kingship became the objects of the peoples’ reverence and supplanted the Nation idea.(49)

The primary cause of decline, then, is internal decay. The Muslim and British invaders could succeed only because the country was already disunited at the time of their arrival, due to want of a common danger. The same point is emphasized when Golwalkar says that

with the passage of time, a sense of security spread its benumbing influence over the whole Nation, and the great corruptor, Time, laid his hands heavily on the people. Carelessness waxed and the one Nation fell into small principalities. Consciousness of the one Hindu Nationhood became musty and the race became vulnerable to attacks from out side.(50)

Elsewhere, Golwalkar makes a similar argument to underscore the point that decay always begins from within.

Dharma is like fire, a source of great power. Just as the fire can burn in an oven to cook a sumptuous meal or can burn down the house itself, so also dharma could be a source of strength and unity as it used to be in olden times, or it could be turned into a source of dissension and disunity as at present.(51)

If an “impending common danger” is needed to constantly reinforce the nation, then the existence of the nation must be seen as a military reality, possessing a wartime quality. Similarly, the maintenance of the five unities is also possible only by confronting external enemies who pose a threat and can disrupt the unity of the nation at any time. The nation represents purity, and purity exists in relation and in disharmony with the impure. It is thus that protecting the nation and its honour becomes the responsibility of every Hindu. The nation, then, is an entity characterized by a foundational contingency, although this is not overtly accepted. In a lecture delivered in Bangalore in 1956, Golwalkar observed, against the grain of the mentality he embodied, that “the concept of ‘nation’ was a positive one and was not based on antagonism to anyone else.”(52) This conscious acknowledgement of the nation as a positive concept militates against the ideological content of the Parivar’s mentality, where the nation is seen as warranting constant protection.

The idiom Golwalkar deploys is one of perpetual confrontation. The examples he cites for the disruption of nationhood are also invariably military in nature. The Jews lost their nationhood due to a loss of territory caused by Roman invasion and tyranny, followed by the destruction caused by Islam.(53) Parsis too lost their territory and therefore nationhood as a result of Islamic invasion of Iran.(54) Germany maintained the purity of its nation by purging it of the Semitic Jews.(55) Such portrayals of the nation abound in much of Golwalkar’s writings. This image is the outcome of a mentality that sees the nation as an entity that needs to be regularly protected from forces of corruption and decay. This is not an idea or a rationally argued theory. It is, instead, a profoundly influential and alluring mentality animated by the false consciousness of time, space and existence.

This ideology of nationhood revolving around specific forms of desire and power gives rise to two important consequences. The first is related to the question of knowledge. The second concerns agency.

In Golwalkar’s writings, awareness—which necessarily means the Hindu national consciousness—is privileged over knowledge. The five unities that make up the nation is something that the Hindus are expected to internalize deep within their consciousness. It is not to be learnt through an intellectual exercise but existentially realized. Golwalkar notes that “the strength of Hindusthan…lies in the Hindu National consciousness.”(56) Further, he says,

No society is entirely free from defects. The European Society, we maintain, is exceptionally defective and consequently in a constant state of unrest. And yet, Europeans, as Nations, are free and strong and progressive. Inspite of their ugly social order, they are so, for the simple reason that they have cherished and do still foster correct national consciousness, while we in Hindusthan ignore this causa causans of our troubles and grope about in the dark, chasing phantoms of our imagination, created by mis-conceptions set afoot by interested hostile parties.(57)

What Golwalkar calls the correct national consciousness is not a piece of rationally produced knowledge but an ontological truth which modern western political scientists were able to discover through their scientific reflections, but which was already known to the great Indian thinkers of yore. Thus, the status of the nation as a geographical, racial, religious, cultural and linguistic unity is not a piece of knowledge to be produced or imparted. It is a reality the Hindu needs to be aware of. In the long peace following the battle of Mahabharata this awareness gradually declined, which was further deepened by the delusions created by “interested hostile parties.” Yet, there were times when this inherent awareness rose above the threshold; “the dormant National consciousness roused itself under Shiwaji and the Sikh Gurus and rejuvenated the Hindu Nation.”(58) The need of the hour is to rekindle this awareness. Never once are we told that the need of the hour is to create an inquisitive mind. According to one pedestrian assessment of the RSS under Golwalkar,

Rational, radical, intellectual understanding or scientific proof is not something that appeals to most people. The vast majority of the RSS wanted that emotional succour, the sense of belonging, and a sense of security. That was available to them as long as they did not start questioning and remained implicitly faithful. In fact, there were very few who said that their understanding and approach was based on the intellectual appraisal of the RSS’ thesis and no other element.(59)

The privileging of awareness over knowledge, and the call for being perennially at the service of the nation, preclude the possibility of producing knowledge about the human world, functionally as well as ideationally. It is therefore understandable that none of Golwalkar’s writings make a call for knowledge production or to nurture an inquisitive mind. Golwalkar’s focus is on reinforcing the Hindu national consciousness, which is also equated with character building.

India has of course been home to such giants as Sankara, Bhaskara, Charaka, Sushruta, Chanakya and Madhava, who produced knowledge in a wide range of areas. This continues even today through the “worthy offspring” of these forebears, like Ramanujan, C.V. Raman, Jagdish Chandra Bose, Birbal Sahni etc. All of them indeed command admiration.(60) But they are not exemplary models. The Hindu is never asked to emulate them or to cultivate a similar intellectual faculty. These towering intellectuals “are the glorious fruit of this ancient culture and bear unimpeachable testimony to its greatness.”(61) So, they ultimately serve only to reify the nation and make it all the more noble, desirable and worthy of possession. “No race is endowed with a nobler and more fruitful culture surely. No race is more fortunate in being given a Religion, which could produce such a culture.”(62) For it has been “indisputably proved” that “Hindusthan is the land of the Hindus and is the terra firma for the Hindu nation alone to flourish upon.”(63)

Golwalkar’s approach to knowledge brings to light the remarkable integrity of the mentality that informs his thought. Knowledge is a product of human volition. There can be no room for it in the scheme of things where the selfhood and agency of the individual are expected to be erased in the interest of the nation.

This brings us to the question of agency. What should the Hindu do today? There is a need to wage a war against a host of enemies. This has to be a total war.

Such a total war, unlike the present limited one, would have involved every one of our countrymen in active participation in an all-out war effort and that would have been a great chastener of the national mind. The long spell of slavery and submissive living under the British has bred many a vice of indolence, selfishness, parochialism, etc., in us. All these vices and weaknesses would have been completely burnt in the fire of a long-drawn war and the pure gold of a united and heroic nationhood would have emerged ever more resplendent.(64)

But Golwalkar never gives a call for such a war. All he expects is that “we should heartily pray for such a war, though we are traditionally instinctive lovers of peace and not war-mongers.”(65)

We have no reason to be afraid of our future. We have no cause to despond. All we have to do to remount our throne is to respond to the awakened Race-spirit and re-rouse our national consciousness, and victory is in our grasp.(66)

In other words, there is no need to train a Shivaji or a Rana Pratap from amidst us. The awakening of the national consciousness will produce its own Shivajis and Rana Prataps. There is, therefore, no call for action. The only call is for awareness about the Hindu national consciousness, which is as much an awareness about the splendours of the Hindu nation as it is an awareness about its enemies. Were we to sum up in humble terms what the RSS really meant to its cadre, this is how it would probably read:

It offered them a target larger than their life but demanded only moderate sacrifice and moderate courage. It gave them a sense of power, of being together and being a part of an organisation. It gave them confidence to face the disadvantages in life at a time when India was poor, starved and had locked itself into a state of stasis. This brand of patriotism and heroism did not demand the courage of revolutionaries.(67)

Action was therefore largely limited to what has been called “constructive work”, which included rescue and rehabilitation works, community development, vocational training and employment, and promotion of deshi goods and commodities, apart from training in martial art and self defense in the shakhas and running of schools in which the curriculum centered on “character building” and inculcation of the “Hindu national consciousness.” The production of Shivajis and Rana Prataps, and the ultimate war to be waged against the enemies of the Hindu nation, were left to be realized in the fullness of time.

A considerable measure of conflict within the RSS and the Parivar has sprung from this humble expectation, which was ill at ease with the other shades of the Hindu nationalist mentality which swore by action and greater political participation, apart from nurturing a virile form of masculinity. According to one detractor, the RSS was originally meant to represent “an achiever’s psyche, not ready to wait but to force itself on the sands of time and bring about change in the situation one had inherited simply through one’s effort…. Golwalkar abandoned the achiever’s psyche.”(68) The opposition to hero worship and sublimation of the individual were both antithetical to the expectations of a large number of members from within the Parivar for whom the realization of nationhood had to be accompanied by the logical corollary of attaining tangible forms of political control. Golwalkar’s model did not envisage or approve of this possibility. The Parivar moved away from Golwalkar’s ideals after the late 1970s. It was the Emergency and the wounds it caused on the nation’s dominant masculinities, and the possibility of political participation which the Janata Party government opened up after the Emergency, that led the Parivar to eventually reconsider its opposition to submissive selfhoods and hero worship, although the Golwalkar model is strongly represented even today by an influential section of the RSS.

Notwithstanding the conflicts within the Parivar, Golwalkar’s modest expectation from the RSS cadre, coupled with the image he presented of a saintly Hindu patriot meditating deeply upon the Hindu national consciousness, had a profound impact on the fortunes of the Hindu nationalist mentality. Golwalkar provided an exceptional ideational grid for the reproduction of this mentality. It turned out to be the greatest enterprise of pedagogic engineering ever in history. The results are there for us to see. In the opening years of the twenty-first century, the RSS had more than three million swayamsevaks,(69) and its women’s wing, about one million.(70) This is greater than the strength of the Indian armed forces, which in 2010 was only 2.48 million strong.(71) No credible estimates exist for the membership in the sister organizations of the Parivar.

The above discussion revolves around only to two popular works of Golwalkar’s. They neither exhaust the RSS oeuvre nor represent all shades of the Parivar mentality. But even this limited corpus of writings has shown the complex and conflict-ridden nature of the Hindu nationalist mentality. They persuade us to posit the emergence of the Hindu right in relation to a larger set of questions involving the generalization and reification of landed property relations and the visages of desire and power that spring from them. They also urge us to situate momentous historical developments like the making of the Sangh Parivar in relation to a variety of problems like knowledge, action and representation. Only then can we arrive at a decent understanding of what the Parivar indeed is. The ongoing academic tirade against the Parivar serves only to reproduce the very mentality and approach towards the Other which animates the politics of the Sangh Parivar.

Notes/references

| 1. |

See Note 69 and 70 below. |

| 2. |

More importantly, there are no scholarly biographies of any of the leading Sangh Parivar leaders like Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar, Deendayal Upadhyay, Shyama Prasad Mukherjee or Lakshmibai Kelkar.

|

| 3. |

Numerous such “critiques” are available. For a representative sample, see Aditya Mukherjee, Mridula Mukherjee and Sucheta Mahajan, RSS, School Texts and the Murder of Mahatma Gandhi: The Hindu Communal Project, Sage, New Delhi, 2008; Ram Puniyani, Communal Politics: Facts versus Myths, Sage, New Delhi, 2003; and A.G. Noorani, The RSS and the BJP: A Division of Labour (Signpost 3), Leftword Books, New Delhi, [2000] 2008.

|

| 4. |

Perry Anderson recently wrote, “More died in the pogrom of 1984 in Delhi covered by Congress, than of 2002 in Gujarat covered by the BJP, although the (sic) latter’s active political complicity was greater. Neither compare with the massacres in Hyderabad under Nehru and Patel.” Perry Anderson, The Indian Ideology, Three Essays Collective, Gurgaon, 2012, p. 158. The number of Muslims killed in Hyderabad soon after its takeover in 1948 is estimated to be between 27,000 and 40,000. Ibid., 90. Nothing is ever said of the 1948 Hyderabad killings while lip service is sometimes paid to the slaughter of Sikhs in 1984. A largely immodest silence prevails in cases where violence is known to have been perpetrated by Muslims, which include the 2012 Assam violence against the Bodos and the violence against the Kashmiri pandits which forced the latter in large numbers to migrate to other parts of India.

|

| 5. |

Noorani, op. cit., p. 2. See also the critique of this position in Ramachandra Guha, India After Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy, Picador, (place of publication not clear), [2007] 2008, pp. 755-56, which is directed against Arundhati Roy, “How Deep Shall We Dig”, The Hindu, 25 April 2004.

|

| 6. |

See Sanjeev Kelkar, Lost Years of the RSS, Sage, New Delhi, 2011, where the author—a onetime RSS activist—records the conflict of interest within the organization.

|

| 7. |

The differences within the Parivar is briefly touched upon in Jyotirmaya Sharma, Terrifying Visions: M.S. Golwalkar, the RSS and India, Penguin/Viking, New Delhi, 2007, p. 112 passim.

|

| 8. |

The fractured and uneven nature of Hindu nationalism is discussed in Paola Bacchetta, Gender in the Hindu Nation: RSS Women as Ideologues, (Feminist Fine Print), Women Unlimited, New Delhi, 2004.

|

| 9. |

Especially Jacques Le Goff, Time, Work, & Culture in the Middle Ages, Translated by Arthur Goldhammer, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1980; Idem., The Birth of Purgatory, Translated by Arthur Goldhammer, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1984; Idem., The Medieval Imagination, Translated by Arthur Goldhammer, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1988; Idem., Intellectuals in the Middle Ages, Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan, Blackwell, Oxford, 1993.

|

| 10. |

Here, and in the rest of this essay, ideology is used in the sense in which Marx deployed it, viz., false consciousness, and not in the “positive” sense in which it has been used since Bernstein and the Bolsheviks.

|

| 11. |

Shamsul Islam, Golwalkar’s We or Our Nationhood Defined, With the Full Text of the Book, Pharos Media, New Delhi, [2006] 2011, pp. 48-49.

|

| 12. |

Ibid., p. 33, 40, 44.

|

| 13. |

It differs from the brand of Hindu nationalism found in the writings of the Rashtra Sevika Samiti, the women’s wing of the RSS, where the difference is spelt out in ontological terms. See Bacchetta, op. cit.

|

| 14. |

M.S. Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts, Third Edition (Revised and Enlarged), Sahitya Sindhu Prakashana, Bangalore [1996] 2011, p. 24. (Emphases as in the original). Note that it is the basis of difference which is articulated ontologically, unlike the case of the Rashtra Sevika Samiti (note 13 above), where the difference itself is ontological.

|

| 15. |

Islam, op. cit., p. 3 of the text. |

| 16. |

Ibid., pp. 2-3. |

| 17. |

GIbid., p. 3. |

| 18. |

This is in disagreement with the primacy given to the family by the Rashtra Sevika Samiti. See Bacchetta, op. cit.

|

| 19. |

Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts, p. 108.

|

| 20. |

Ibid., p. 110. |

| 21. |

Islam, op. cit., p. 61-62 of the text.

|

| 22. |

Ibid., p. 62. |

| 23. |

Sharma, op. cit., pp. 3-7. |

| 24. |

Kelkar, op. cit.

|

| 25. |

Bacchetta, op. cit., 30, 41 passim.

|

| 26. |

Sharma, op. cit., p. 3. |

| 27. |

Islam, op. cit., p. 5-6 of the text.

|

| 28. |

Ibid., p. 18. |

| 29. |

Ibid., pp. 17-18. Jeffrelot identifies Hole-Combe as Arthur Norman Holcombe, Bluntsley as Johann Kaspar Bluntschli, Gumplovic as Ludwig Gumplovicz and Getel as Raymond Garfield Gettell, Christophe Jeffrelot, Religion, Caste, and Politics in India, Primus Books, New Delhi, 2010, pp. 129 & 141. |

| 30. |

Ibid., pp. 52-54.

|

| 31. |

Ibid., pp. 54-56. |

| 32. |

Ibid., p. 56. |

| 33. |

Ibid., p. 3. |

| 34. |

Ibid., p. 10, passim.

|

| 35. |

Sharma, op. cit., p. 4.

|

| 36. |

Islam, op. cit., p. 59. of the text.

|

| 37. |

Ibid. |

| 38. |

Ibid., p. 60. |

| 39. |

Ibid., pp. 6-7. (Emphases added). |

| 40. |

Ibid., p. 6. (Emphasis added).

|

| 41. |

Ibid., p. 3.

|

| 42. |

Ibid., p.9. |

| 43. |

Fredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 1981, p. 157.

|

| 44. |

Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts, p. 170.

|

| 45. |

Ibid., p. 93.

|

| 46. |

Ibid., p. 85.

|

| 47. |

Ibid., p. 87.

|

| 48. |

Ibid. |

| 49. |

Islam, op. cit., p. 57-58 of the text. (Emphases added).

|

| 50. |

Ibid., pp. 9-10.

|

| 51. |

Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts, p. 107.

|

| 52. |

Ibid., p. 120..

|

| 53. |

Islam, op. cit., p. 19 of the text.

|

| 54. |

Ibid., p. 20. |

| 55. |

Ibid., p. 35.

|

| 56. |

Ibid., p. 59.

|

| 57. |

Ibid., p. 62. |

| 58. |

Ibid., p. 58. |

| 59. |

Kelkar, op. cit., p. 54.

|

| 60. |

Islam, op. cit., p. 41-42 of the text.

|

| 61. |

Ibid., p. 42.

|

| 62. |

Ibid. |

| 63. |

Ibid., p. 45.

|

| 64. |

Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts, p. 326.

|

| 65. |

Ibid.

|

| 66. |

Islam, op. cit., p. 67 of the text.

|

| 67. |

Kelkar, op. cit., p. 56. |

| 68. |

Ibid. |

| 69. |

Bacchetta, op. cit., p. 5. |

| 70. |

Ibid., p. 12. |

| 71. |

This includes 1,325,000 active and 1,155,000 reserved soldiers. James Hackett (ed), The Military Balance 2010: The Annual Assessment of Global Military Capabilities and Defence Economics, The International Institute of Strategic Studies/Routledge, London, 2010, p. 359. Even if we were to include the paramilitary forces, (2,288,407, Ibid.) the figure would not reach five million.

|

Manu V Devadevan is Assistant Professor of Humanities and Social Sciences at IIT Mandi, Himachal Pradesh. His areas of interest includes literary practices in South Asia, Indian Epigraphy, history of asceticism, political economy of premodern Asia, and contemporary politics.

|

|