|

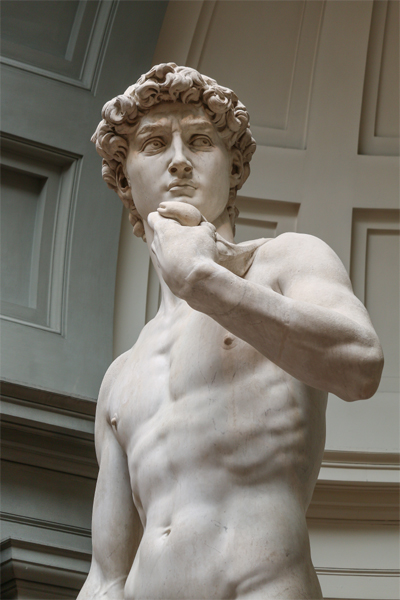

This is essentially an attempt to examine the western and traditional Indian approaches to art and literature. I am conflating the two on the assumption that what is said about one of them will broadly apply to the other and ‘art’ includes not only the visual/plastic arts but also music and performance like dance and theatre. Many western philosophers beginning with Plato and Socrates regarded art as ‘useless’ because it imitated (‘mimesis’) what was in the real world without transforming it to make it better. Kant’s view freed art from content, subject matter, the wishes of the patron or the client, the community’s demands and the needs of religion. The idea was of art being given wholly to aesthetic pleasure and delight and the freedom to exist on its own terms and in a universe of its own. This essay is speculative and the issue it deals with is what the ‘relevance’ of art and literature would be - given that the usefulness of art and literature is not entirely clear. But before I proceed further, I must make the admission that the discussion will begin by being Eurocentric since western views of art and literature dominate discussions on the subject. Indian ideas of art and literature are not quite the same and I will go on to them thereafter. This is essentially an attempt to examine the western and traditional Indian approaches to art and literature. I am conflating the two on the assumption that what is said about one of them will broadly apply to the other and ‘art’ includes not only the visual/plastic arts but also music and performance like dance and theatre. Many western philosophers beginning with Plato and Socrates regarded art as ‘useless’ because it imitated (‘mimesis’) what was in the real world without transforming it to make it better. Kant’s view freed art from content, subject matter, the wishes of the patron or the client, the community’s demands and the needs of religion. The idea was of art being given wholly to aesthetic pleasure and delight and the freedom to exist on its own terms and in a universe of its own. This essay is speculative and the issue it deals with is what the ‘relevance’ of art and literature would be - given that the usefulness of art and literature is not entirely clear. But before I proceed further, I must make the admission that the discussion will begin by being Eurocentric since western views of art and literature dominate discussions on the subject. Indian ideas of art and literature are not quite the same and I will go on to them thereafter.

The first thing noted about art is not only that there is imitation of reality - nature, society and the man-made world – inevitably at work but that it has ‘progressed’ in some sense, the direction of the progress being towards a closer imitation of the world in terms of its likeness to it. When Dante described hell in The Inferno or Hieronymus Bosch painted it in ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’, they actually believed that hell was as depicted and it was not intended to be fanciful. Imitation in art meant replicating what was in the real world and the works were infused with the meaning that the world itself – due to God’s laws – was seen to possess. But we have a paradox here which is that while art was only seen as imitative and unable to transform reality – which was held against it – it was also feared as dangerous and works of literature were often burned as blasphemous, and painters as well as writers persecuted. The Islamic proscription of art (painting, music) may be taken to relate to this same notion. (1)

With the advent of photography - and subsequently cinema - art began to lose its importance as an imitation of reality since humankind had now invented the mechanical means to do that much better and without human involvement. Art therefore increasingly moved towards subjectivity and expression instead of simply imitating the existing world. Art - from Impressionism onwards - is taken up more with human perception. One could say that a key aspect of high modernism in art and literature was the admission of subjectivity and expression into it, since the world ‘as seen by God’ no longer made much sense. At around roughly the same time, i.e.: the early twentieth century, science also discovered subjectivity, and modern physics therefore moved away from classical physics in this key sense. Modern physics introduces the ‘unknowable’ as an element – like absolute velocity – and modern art, by no longer being concerned with the world ‘as God made it,’ may be seen as a parallel. To elaborate, classical physics assumes a world independent of the observer (i.e.: as ‘God made it’) but modern physics places the observer in it. Modern art introduces subjectivity in the shape of the artist expressing himself or herself.

Much of modern art would not have been accepted a century earlier as art but ‘progress’ in art means that art is entirely dependent on the context in which it is produced; it cannot be taken out of that context for it to have value. It is for this reason that when tribal art resembles the work of Matisse or Picasso it is not that tribal artists have anticipated modernist painting but that modern art came out of a different context - although to the lay person the two may appear alike.

One of the earliest conflicts seen (by the Greeks) was that between art/poetry and philosophy. While the latter was seen as conceptual/rational and in search or solutions to problems, the former were derided as sensuous, emotional and imagined with no ability to bring about understanding. But now we could say that art and literature are valuable because they imply ‘irrational truths’ - both subjective and objective - although it would take interpretation to excavate them. By irrational truths I mean the expression of subjective states including those pertaining to anxieties that are not objectively ‘real’ but are nonetheless important aspects of human existence. Since it is also difficult to clearly segregate the objective from the subjective, ‘objective reality’ is in effect often contaminated by the irrational. Art/literary criticism, ideally, bridges the gap between art or literature and philosophy since it tries to explain ‘artistic truths’ in rational/conceptual terms, and comment upon their social validity since all art is not equally valuable to human society. Critics pass judgement only after undertaking this exercise. While examples from art and literature could be intensely personal, they are the products of social interactions – since they have also to be expressed in a language that is shared – and are consumed by society, which means that their purpose and impact are essentially social.

If the purpose of art and literature are essentially social it also follows that they must be relevant to the moment, but they could take several shapes. Firstly, a work might be explicitly social and a representation of how things are, which cannot include a reference, however covert, of how things might be. In such cases the work might include an element of persuasion and even become propagandist for a socio-political viewpoint. Or, the work might be symbolic or allegorical dealing with the socio-political present in other terms though it may not always be conscious of that (2). An instance would be American superheroes like Superman and Spider-Man dressing in blue and red, the colours of the national flag, implying socio-political concerns.

When the work is psychological or religious there is still a community it is addressing. It is also presenting a picture of the world perceived, although expressing emotions in relation to it. Even totalitarian societies with strict censorship cannot prevent art and literature and they become ways of expressing or narrativizing social experience in permissible ways - where truths are still recognizable, however couched they may be in politically innocuous language. We could say that reality is nothing in itself without the overlay that art and literature provide and these are hence key elements in the ‘culture’ of any society. Culture is the sum total of the ideas, customs, and social behaviour of a particular people or society but (because art/literature persuades) one could get an idea of what society should be in order for it to reach its potential. It can thus position its discourse as dissent or a critique of the reality it is depicting.

Emotions and the arts

People have generally assumed that that there is some special deep connection between emotion and the arts. In The Republic Plato famously complained that one reason why poetry often has such a bad moral influence on people is that it appeals to their emotions rather than to their reason, which he called the ‘highest’ part of the soul. The idea that the emotions are intimately connected to the arts was taken up by Aristotle more sympathetically. Ever since, there has been a widespread conviction that there is some special relationship between the arts and the emotions (3).

For most people the answer to the question ‘what is an emotion?’ is that emotions are ‘feelings.’ However even if experiencing emotions does involve having feelings, we cannot simply identify emotions with feelings since there are many feelings that are not emotions: hunger pangs, sexual urges, and various itches and tickles, feelings of hot and cold, of heartburn and muscular pain. Regardless of how a person’s body might respond when he/she sees a beloved, love is not simply that bodily response.

An accepted view today is that emotions are the results of cognitive processes (conscious mental activity) induced by judgement and two different kinds of judgements may produce the same physiological result (like increased heartbeat). The difference between remorse and regret is cognitive: when one experiences regret, one judges that something untoward has occurred for which he/she may or may not be responsible and wish that it had not happened, whereas when one experiences remorse, he/she judges that he/she has acted in a way morally bad and for which he/she bears responsibility (4). In their discussions of emotion, philosophers from Aristotle to Hume have emphasized the cognitive content of emotions. Aristotle defined anger as ‘a desire for revenge accompanied by pain on account of an apparent slight to oneself or one’s own, the slight being unjustified’. An emotion is a process of interaction between a human being and his/her environment depending on the person’s interests, as in this case where a slight is made. But if emotions are only felt in relation to our interests (because ‘something happened to me’) what would we say about the emotions aroused by art and literature?

If a work of literature is to make us understand something, the first question that needs to be asked is how arousing our emotions can make us do that. If one is angry or sorrowful, one is not in a good state for understanding anything. Far from helping one to understand a novel one’s own feelings may distract from it. One should be trying to understand the novel itself and its qualities, rather than focusing on one’s own feelings, which may be idiosyncratic, leading away from the work. There are many times when the emotions aroused by a story do not help understanding. If a novel helps us to understand it, one might still think it possible to come to the same understanding by a more cerebral engagement with the text. But without appropriate emotional responses, some novels simply cannot be adequately understood (5). What does it mean to become emotionally involved in the characters, situations, and events recounted in a novel?

First of all, one will not have any emotional response to a novel unless one senses that one’s own interests, goals, and wants are somehow at stake. The story has to be told in such a way that the reader cares about the events it recounts. We react to the characters in a way that suggests that we feel my own wants and interests to be at stake in what happens to them. We may also experience action tendencies: perhaps we want to help a character and have a tendency to act to achieve this. This could roughly be termed ‘experiencing’ a novel or a literary work. But this by itself is hardly to ‘understand’ something and we fill in gaps and infer causal and other relationships. Something has happened to someone for factors that may not even be spelled out. In Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis a man wakes up one morning and finds himself having become a gigantic beetle and no explanations are offered but we reflect on what it means. But experiencing a narrative is not the same thing as interpreting it. It is important to distinguish between experiencing the work, responding on our experiences of it as they occur, and interpreting it by reflecting on and estimating our experiences of the work after finishing it, by summing it up as a whole (6).

At the simplest level, when we infer why something happened or why someone suffered unnecessarily, we reach an understanding that merely identifying with characters does not impart. There are so many aspects to a work of literature that it creates a world for us to immerse ourselves in and we allow it to envelop us with its own internal laws that supplant those of the actual world when we are immersed in it. When we are out of the novel and in the real world, we do not altogether forget it but, if it has been powerful enough, tend to see real happenings in its light until its effect wears off. Sometimes its effects are so powerful that they influence us for larger periods. The laws governing the actual world can never be fully known but a great work of literature can convince us, however briefly, that its own world is like the real one.

I noted the tendency in modern art to move away from imitating the world to ‘expression’ and this is true of much of modernist literature, which has also admitted the subjective element. Evidently ‘expressionist’ literature (of which Kafka’s Metamorphosis is an example) has less correspondence with the actual everyday world but we recognise our own feelings about the world in such literature - and see even fantastic literature as ‘mimetic’ in the sense that the imitation is not of the world as it is but as it is perceived by many. A ghost story, for instance, could incorporate our fear of the unknown by manifesting it in unexplained occult phenomena.

If realistic literature helps us identify with characters, feel what they are feeling and suffer on their behalf, evidently there are other forms of art like theatre and even dance that try to do the same things more expressionistically through stylised representations. Figurative painting through realistic depictions could make us identify with situations (like the crucifixion of Jesus) and people (as in portraits) and appreciate nature as actual nature could be appreciated (in landscapes). Many great paintings try to seize a moment in a familiar narrative (say from an epic or mythology) and imitate that. This brings us to why we find the picture of an apple superior to a real apple that it is imitating which is because of the pleasure it affords the viewer in the craft of imitation. Paul Cezanne’s apples are not even perfect apples but small and wizened but they are still extraordinary, perhaps because they betoken the imperfection of Creation. Here is an explanation offered by art critic Arthur Danto for why the imitation is often better than the real thing:

Aristotle, who explains the pleasure men take in art through the pleasure they take in imitations, is clearly aware that the pleasure in question (which is intellectual) logically presupposes the knowledge that it is an imitation and not the real thing it resembles and denotes. We may take (a minor) pleasure in a man imitating a crow-call of a sort we do not commonly take in crow-calls themselves, but this pleasure is rooted in cognition: we must know enough of crow-calls to know that these are what the man is imitating…and must know that he and not crows is the provenance of the caws. These crucial asymmetries need not be purchased at the price of decreased verisimilitude, and it is not unreasonable to insist upon a perfect acoustical indiscernibility between true and sham crow-calls, so that the uninformed in matters of art might-like an overhearing crow, in fact-be deluded and adopt attitudes appropriate to the reality of crows.…So the option is always available to the mimetic artist to rub away all differences between artworks and real things providing he is assured that the audience has a clear grasp of the distances (7).

All this is true of figurative art but what about abstract art where what we see are often no more than splashes of colour; what aspect of the real world is it imitating? I would respond by saying that abstract art is closest to music; this proposition leads us to music, which is the most difficult to explain in the terms I have just set out. I do not refer to the lyrics in music which would be literature but the music itself. What does music portray since we do not find any obvious imitation of the world in it? A solution offered is that it represents human feelings:

“(T)here are certain aspects of the so-called ‘inner life’—physical or mental—which have formal properties similar to those of music—patterns of motion and rest, of tension and release, of agreement and disagreement, preparation, fulfilment, excitation, sudden change, etc.” (8)

This is evidently not adequate and we need to know more, such as how such a relationship between feelings which are personal and something manifested in the organization of sound in the outside world can happen. An argument is that to hear music as expressive is to anthropomorphize or ‘animate’ the music: we must hear an aural pattern as a vehicle of expression—an utterance or a gesture—before we can hear its expressiveness in it. To elaborate we try to make an association between the quality of the music and human conduct in the face of certain feelings. An illustration offered is the sad face of a St Bernard dog. Obviously its sad face is simply us seeing the dog’s face in human terms since sadness is not a quality of the dog’s feelings as our own association with a similar-looking human face. Peter Kivy (9) argues that music can be similarly expressive of an emotion without being an expression of anyone’s emotion, just as the dog’s face is expressive of sadness without being an expression of its own sadness: Music is expressive by virtue of its resemblance to expressive human utterance and behaviour.

From the above discussions it would seem that all forms of art and literature are fundamentally mimicking the real world and human experience in some way. The real world is not simply the physical world but has human emotion and expressivity as a key component and the movement away from straightforward imitation of external reality happened when mechanical devices were able to capture the real world better. The world, it would seem, is increasingly understood to be not knowable in its entirety and the arts are a way to introduce the subjective element into its perception by humankind. We may now look at the arts in India and the purpose they are intended to serve.

Traditional Indian aesthetics and mimesis

What is being said in this section pertains broadly to aesthetics, poetics and dramaturgy and no distinction is being made since there is continuity between them. Indian aesthetics, it is often said, consists fundamentally of the notion of rasa – the term rasa being translated variously as ‘flavour’ or ‘desire’ or ‘beauty’: that which is ‘tasted’ in art (10). The essential quality of the aesthetic experience is neither subjective nor objective; it neither belongs to the artwork or the one who experiences it. It is rather the process of aesthetic perception itself, that which defies spatial designation that constitutes rasa. The rasa is a generalised emotion, one from which all elements of particular consciousness have been expunged: such as the time of the artistic event, the preoccupations of the audience and the specific individuating qualities of the artistic work itself. Persistence of elements of particularity would amount to an obstacle (11). The purpose is for the audience and the players and even the critics to lose the sense of their separate psychological identities (12), which arguably implies or suggests the union of atman and paramatman.

This above philosophical analogy is specifically reminiscent to Advaita Vedanta but there were various other philosophical schools in India as well, like that of the Carvakas (materialists). But, by and large, Advaita Vedanta – despite being abstruse – carried a philosophical weight that led it to be taken as the culmination of philosophical thought in Hinduism although the heterodox schools opposed it: Here is a speculative account of why it happened:

“Its propagation in the wider public sphere and its professional pursuit in the academia was largely determined by diverse considerations such as (a) to assert that science, i.e. scientific knowledge of phenomena (apara vidya) needs to be complemented by a synoptic vision of reality (para vidya); (b) to register the national identity as a form of self-assertion; and (c) to negotiate with the dominant Western philosophers and their philosophies; especially, the Bradleyan version of Hegelian Idealism on equal terms. For achieving these objectives, the Advaitic doctrine of Brahman proved to be more promising than any other doctrine from any other school of Indian philosophy.” (13)

This pertains to its supremacy in the modern age but it would seem that even much earlier (the Natyasastra is dated to 500 CE at the latest) some earlier version (the idea evolved in its details from the Upanishadic age onwards) was most influential in high culture. We could infer that even if there were materialist and other heterodox schools, Advaitic idealism still held sway and was the most influential in the development of Indian aesthetics and dramaturgy in ancient India. Advaitic idealism does not deny the evidence of the senses but subordinates it to ‘absolute truth.’

Art is hence a kind of mimesis according to the rasa theory but it is an imitation of a special kind. Rasa does not imitate actions and things in their actuality or particularity but rather in their potentiality and their universality. This ‘imitation’ is said to be more real than any particular real thing. The generalised emotion is not to be confused with a mere abstraction or dispassionate state of being. To depersonalise in art does not mean to destroy personality but to attain a cognitive state that spiritual in character. The rasa theory identifies eight (or nine since there is some disagreement) innate emotional states that exist in the mind as deriving from one’s past experience and these are the same for everyone since they come from common human life-experience. (14)

The rasas nominally encompass a wide range – pleasure or delight, laughter, sorrow or pain, anger, heroism, fear, disgust, tranquillity and wonder. But the emotions do not quire correspond to what emotions are created by mimesis. If we take horror or terror (which are not quite the same) as an emotion awakened by a film in a David Cronenberg film like The Fly (1986) it is a sense of contamination of the body that arouses deep seated dread within oneself as a psychological state and I attribute it to our sense of self being closely tied to the body since that is the seat of the self and identity. The bhayanaka rasa (terror), for instance, is represented in theatre as follows:

“The presentation of Bhayanaka rasa on the stage is through the Anubhavas such as Pravepitakaracarana (trembling of the hands and feet), Nayanachalana (movements of the eyes), Pulaka (hairs standing on ends), Mukha Vaivarnya (Pallor in the face), Svarabheda (change of voice and tone) and the likes. The Vyabhichari bhavas are Stambha (Paralysis), Sveda (Perspiration), Gadgada (Choked Voice). Romanca (horrification), Vepathu (trembling), Svarabheda (change of voice or tone), Vaivarnya (lack of luster), Sanka (suspicion), Moha (fainting), Dainya (dejection), Avega (Agitation), Capala (restlessness), Trasha (fright), Apasmara (epilepsy or loss of memory), Marana (death) etc.” (15)

From the above it would appear that bhayanaka rasa deals a demonstration of the effect that fear has on a person. It does not attempt to induce that feeling in the audience as a psychological state. If we take a ghostly narrative (say the film The Innocents – 1961- based on a Henry James story) the ghost is a manifestation of evil in the past and introduces an element for which there is no rational explanation, implying a hostile universe that will not submit to a desirable human order. The film induces that emotion in us as appropriate to what it is implying. The corruption of two children by the malevolent forces in the film substantiates this hypothesis. Traditional Indian theatre is not trying to frighten or induce horror in the spectator but trying to represent horror or terror as a part of life; drama itself cannot be entirely devoted to one emotion as is possible in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974). It is in fact an aggregate of model situations and tries to accommodate a wide range corresponding to life as lived (16).

Indian dramaturgy, aesthetics and poetics also lay down the purposes of the arts and literature. In the first place it (specifically drama) would be instructive to all through actions and states depicted (17) while should be a diversion for people weighed down by sorrow or fatigue or grief or ill-luck; it should be a rest for the body and the mind (18). This ‘mimesis while not being mimesis’ has confused western students of Indian culture when some of its prescriptions have invited comparison with Aristotle who held that while history related what actually happened, poetry/art related what may happen and dealt with potentialities. Here is a scholar on this aspect: Indian dramaturgy, aesthetics and poetics also lay down the purposes of the arts and literature. In the first place it (specifically drama) would be instructive to all through actions and states depicted (17) while should be a diversion for people weighed down by sorrow or fatigue or grief or ill-luck; it should be a rest for the body and the mind (18). This ‘mimesis while not being mimesis’ has confused western students of Indian culture when some of its prescriptions have invited comparison with Aristotle who held that while history related what actually happened, poetry/art related what may happen and dealt with potentialities. Here is a scholar on this aspect:

“The distinction between ‘literature’ in the specific sense, from ‘literature’ in its all-encompassing meaning is both a socio-historical problem….and a formal one…..(traditional) Indian critics never stray far from this central problem: defining the difference of literature vis-à-vis other conventions of expression, science and narrative …But the Indian materials present us with no theory of art for art’s sake, which would simplify our task…Poetic theorists remain acutely aware of the extrinsic purposes and rewards of the poetic act, and both poets and poeticians seem to acknowledge and to serve the vital context in which the poet works. Kavya, though it is a kind of language different in itself, is not seen apart from and indifferent to the social and intellectual dimensions of the language, or to society itself. If anything its difference is seen in its preeminence, in its being fully exploited expression – whose principle is not subordinate to an external standard – indeed reflecting the authoritative status of the Sanskrit language.” (19)

We may infer from the various aspects of Indian aesthetics just detailed that while Indian art, poetry and drama did imitate the world and human actions, it was not mimetic in the sense described earlier and that there specific emotions that they needed to address and for a specific social purpose. It would take more elaboration than is possible here but this sense of art being greater than the real as well as the claim that at the culmination of the aesthetic experience the rasika (connoisseur) will be forced into a silent understanding of the unity of the world and his/her part in it (20) brings it close to the world fully apprehended through the mystical experience. This would account for bhayanaka rasa not trying to induce fear but showing it as a part of life. Since the ‘ultimate truth’ is knowable and art/literature/drama’s purpose is to give the rasika a glimpse of it, the arts together can only present one with the familiar, although in different variations.

But the sense of life having one meaning to be suggested briefly by drama has its share of difficulties since the meanings cannot be fixed in today’s context. One could argue that as humankind advances, human experience itself undergoes transformation and movements of the modern epoch (such as surrealism, magical realism, the absurd, cubism) have arisen out of it. Historical developments ranging from the Holocaust (21) to the Internet have transformed the nature of literature/art/drama and when one reads the classics one is therefore reading them in context (their ‘particularity’) and not in their ‘universality’. Hence, if the portrayed emotions are restricted to a definite number, is not the ‘relevance’ of the forms of art and literature that emerge itself compromised?

Whether the rasa theory has in its capacity to express emotions like despair and absurdity has been asked before and discussed. Here I would cite Sharad Despande 22 who examines Ashis Nandy and Prem Shankar Jha who felt that it did not. Here is Deshpande discussing Ashis Nandy on despair as an emotion:

“Nandy …observes that the feeling of despair is alien not only to the Indian but to many ancient cultures, including the pre-modern Europe. Why this is so is to be understood in a wider sociological perspective rather than taking it to be a mere art-historical fact. Individual and isolated instances representing despair in artistic creations apart, it is claimed that it is only in the modern times that despair as a full blown existential state has ‘acquired a serious moral, philosophical and aesthetic status’. In other words, ‘despair’ as an autonomous philosophical category has its origin in modernity. This line of argument suggests that the emotions or states of consciousness that human beings have are historically determined, that rather than being rooted in the human psyche they are caused by the socio-politico-economic conditions in which humans live….Sociologists and the historians of cultures have described the difference between the modern and the pre-modern traditional cultures in terms of ‘holistic vision’ that enabled the traditional cultures view not only the human beings but also the entire natural world as one ‘indivisible’ whole. The culture that views the nature and the man–nature relationship in its wholeness also views man’s relation with others as forming a web of social relations.” (23)

All three (Nandy, Jha, Deshpande), we may note, are approaching artistic expression through emotions - those that are nameable - and finding some of them to be specifically modern. It could be argued that this owes to the preoccupation with the self and interiority in the Indian tradition. If one’s preoccupation with one’s self - and one’s worldview is idealistic in this sense - emotion is the primary way in which one would approach artist expression. But I would contest the view that art proceeds primarily from emotions at all and also that all representable emotions are nameable. Kafka, for instance, is taken to be a ‘modernist’ writer but are the emotions in his story ‘The Great Wall of China’ comparable to those created by Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot, i.e.: subsumable under the term ‘absurd’ as one might suppose from what Deshpande and the others argue? Jorge Luis Borges (24) detects ‘Kafkaesque’ elements in Zeno’s paradox of ‘Achilles and the Tortoise’ and Zeno lived in the 5th century BCE. The only solution, it seems to me, is not to regard artistic expression as grounded primarily in emotions but in the experience of the real world and to hence treat it as imitation – but with the subjective element included. There is also the issue of interpretation: every receiver of a text may not find the same emotions (for instance if irony is detected by one and not so by another) in it. Mimesis allows for different interpretations but the rasa theory apparently does not.

There is another issue that has to do with the notion of experimentation in the arts and the avant-garde. These exist because of our uncertainty with regard to the purpose of art and what it aims at. If that is prescribed – as traditional Indian aesthetics, poetics and dramaturgy have it – there could not be experimentation. The notion of the ‘rasika’ is also something that may have outlived its usefulness since the arts strive to reach a large public - and having a special category in the ‘connoisseur’ who alone will determine if a work of art or literature succeeds or fails seems impossible. Moreover, the notion was intended for an age when there was agreement about art forms and the forms were themselves pure but in the modern age there are so many influences from without – leading to artistic and literary hybrids - that the rasika’s opinion (as that of a purist) may not have much validity except in the classical forms of art/performance. It should be noted that the rasika is not a critic since the critic often goes beyond the effect produced by the text, for instance into interpretation. The rasika stays within the boundaries set by the work/performance and relies on classical theories to pass judgement.

The future of the arts in India: grounds for state intervention

While admitting the validity of Indian aesthetics/poetics/dramaturgy they seem appropriate to a view of the world that may not admit many historical developments of the modern age as subjects deserving expression. Evidently the theories have to be studied and valued for what they are but they should perhaps be treated as a special category and compartmentalised. This might mean studying them in context and especially in their pertinence to traditional forms of art/ literature/ performance in India.

But after this has been said, it is the classical tradition in art/literature/performance that is under threat since - whether consciously or not - western practices/notions will gradually enter the Indian domain since that is the dominant mode. If state action/intervention is contemplated – as it should be – it would make sense for it to put most of its weight behind preserving traditional knowledge. There could also be an added emphasis on informed criticism and its development. The rasika may be an outmoded concept while dealing with modern forms in the arts and literature but it would still be very valuable to a rejuvenated classical tradition.

In dealing with the traditional arts in India, we have not admitted how contemporary Indian art and literature do not consciously adhere to classical theories at all and it is only the performance-based arts – music, theatre and dance mainly – where the classical tradition is still alive. The reason is perhaps that literature and art today – since their commitment to social transformation is demanded – are those most mimetic by necessity (25) and they have abandoned classical theories in their current practices as irrelevant, as I have argued here. Still, one may be sure that aspects of Indian aesthetic theory or concepts are so deeply internalised that they appear in representations and still inform literature and art (including at cinema) in some way (26). In popular cinema, for instance, the representation of romance continues to owe much to the sringara rasa. I cannot argue that classical poetics and aesthetics can be redeveloped to inform practice – i.e.: create artists and writers adept at traditional forms of literature and art for contemporary India – but research in the possibility of the classical theories being adapted for the modern age could still be pursued. Evidently this will need state intervention or some support from private agencies promoting/preserving traditional Indian culture.

Notes/References

1. |

Islamic religious art differs from Christian religious art in that it is non-figurative since many Muslims believe that the depiction of the human form is idolatry, and thereby a sin against God, forbidden in the Qur'an. Calligraphy and architectural elements are given important religious significance in Islamic art since the objects depicted are man-made and not natural. As regards music, “The words 'Islamic religious music' present a contradiction in terms. The practice of orthodox Sunni and Shi'a Islam does not involve any activity recognized within Muslim cultures as 'music'. The melodious recitation of the Holy Qur'an and the call to prayer are central to Islam, but generic terms for music have never been applied to them. Instead, specialist designations have been used. However, a wide variety of religious and spiritual genres that use musical instruments exists, usually performed at various public and private assemblies outside the orthodox sphere. Eckhard Neubauer, (Revised by Veronica Doubleday), ‘Islamic religious music,’ New Grove Dictionary of Music online.

|

2. |

Frederic Jameson famously proposed that all Third World texts could be read as national allegory. While private life has developed as a separate space in the developed world it is much less so here and all narratives will have public connotations. Frederic Jameson, Third World literature in the age of Multi-national Capitalism, in C Kolb, V Lokke (ed)., The Current in Criticism, West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, 1987, pp 131-163.

|

3. |

This is a factor in Indian aesthetics too with ‘rasa’ being associated with a particular emotion that the work tries to create.

|

4. |

Jenefer Robinson, Emotion and its role in literature, music and art, Oxford: Clarendon, 2005, p 8.

|

5. |

|

6. |

|

7. |

Arthur C Danto, ‘Artworks and Real Things’, Theoria, Vol. 39, Issue 1-3, April 1973, p 3.

|

8. |

Susanne K. Langer, Philosophy in a New Key, 3rd edn. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1976, p 228.

|

9. |

Peter Kivy, The Corded Shell: Reflections on Musical Expression, Princeton University Press, 1980, p 56.

|

10. |

Eliot Deutsch, ‘Reflections on some aspects of the theory of Rasa,’ in Rachel Van M Baumer, James R Brandon (eds.) Sanskrit Drama in Performance, Delhi: Motilal Banarasi Das, 1993, pp214-225.

|

11. |

Edwin Gerow, ‘The persistence of classical aesthetic categories in contemporary Indian literature’ in EC Dimock Jr, Edwin Gerow, and JAB van Buitenen (eds.) The Literatures of India: An Introduction, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974, pp 212-239.

|

12. |

Edwin Gerow, rasa as a category of Literary Criticism: what are the limits of its application?’ in Rachel Van M Baumer, James R Brandon (eds.) Sanskrit Drama in Performance, p 236.

|

13. |

Sharad Deshpande, G.R. Malkani: Reinventing Classical Advaita Vedanta, In Sharad Deshpande (ed) Philosophy in Colonial India, Delhi: Springer, 2015, p 120.

|

14. |

Eliot Deutsch, ‘Reflections on some aspects of the theory of Rasa,’ in Rachel Van M Baumer, James R Brandon (eds.) Sanskrit Drama in Performance, p 217.

|

15. |

|

16. |

M Christopher Byrski, Sanskrit Drama as an Aggregate of Model Situations, from Rachel Van M. Baumer and James R Brandon (Eds.) Sanskrit Drama in Performance, p143.

|

17. |

Farley P Richmond, Origins of Sanskrit Theatre, from Farley P Richmond, Darius L Swann, Phillip B Zarrilli (Eds.), Indian Theatre: Traditions of Performance, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidas, 1993, pp 25-6.

|

18. |

Natyashastra 113-114 Quoted in Lothar Lutze. From Bharata to Bombay: Change and Continuity in Hindi Film Aesthetics, from (Eds.) Beatrix Pfleider and Lothar Lutze, The Hindi Film: Agent and Re-agent of Cultural Change, Delhi: Manohar Publications, 1985, p 8.

|

19. |

Edwin Gerow, Indian Poetics, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1977, p 220.

|

20. |

Eliot Deutsch, Reflections on Some Aspects of the Theory of Rasa, from (eds.) Rachel M Van Baumer and James R Brandon, Sanskrit Drama in Performance, p 223.

|

21. |

Even classical music in the west has incorporated themes like Hiroshima and the Holocaust and instance would be the music of Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki.

|

22. |

Sharad Deshpande, Emotions in Indian-Thought Systems, Oxford: Routledge, 2015, pp 266-280.

|

23. |

Ibid, p 275. Also see Ashis Nandy, ‘Foreword’, in Harsha Dehejia, Prem Shankar Jha and Ranjit Hoskote (eds.), Despair and Modernity: Reflections from Modern Indian Painting, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2000, pp. vii–xv; Prem Shankar Jha, 2000. ‘Sociology of Despair’, in Harsha Dehejia, Prem Shankar Jha and Ranjit Hoskote (eds.), Despair and Modernity: Reflections from Modern Indian Painting, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 9–25.

|

24. |

Jorge Luis Borges, ‘Kafka and his Precursors, Labyrinths, New York: New Directions, 1962, pp 190-192.

|

25. |

A large part of modern literature, for instance, is taken up with issues like intolerance, inequality and social injustice that were simply not in the repertoire of classical texts. They would have to rely much more on western modes of representation.

|

26. |

Edwin Gerow, ‘The persistence of classical aesthetic categories in contemporary Indian literature’ in EC Dimock Jr, Edwin Gerow, and JAB van Buitenen (eds.) The Literatures of India: An Introduction, pp 212-239.

|

MK Raghavendra is The Founder-Editor of Phalanx.

Courtesy: Michelangelo Fir

Courtesy: Chola bronze Darasuram

|

|