|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Home > Contents > Article: MK Raghavendra

|

|

|

The Dismemberment of Collective Life

Three Films by Vadim Abdrashitov

MK Raghavendra

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Censorship is the origin of metaphor.”

Jorge Luis Borges

An outsider’s perspective:

An outsider’s perspective:

To an outsider who speaks no Russian and has seen only the few subtitled films by Vadim

Abdrashitov the problem of approaching them as an interpretive critic i is a difficult one to

surmount. One needs to match one’s enthusiasm – which is not easy to explain – with a

reading that, while acknowledging that the stimuli the film-maker responded to were largely

local, still tries to seek out more ‘universal’ explanations. Abdrashitov is a difficult

filmmaker, who ostensibly tries to deal with socio-political experience pertinent specifically

to Russia, but if there was not something in them which might be comprehensible to other

societies, it would be difficult to explain their impact upon the spectator with only an

approximate sense of Soviet history and politics. This essay is, roughly speaking, an inquiry

into what Abdrashitov (and his scriptwriter Alexandr Mindadze) may be attempting, with

broader political connotations not restricted to the former USSR but reflecting on issues like

nationhood and collective life.

Film is not a language like English or Greek because it arrived at various centres in the late

19th Century across the world without a primer accompanying it. As Christian Metz declared,

“It is not because the cinema is language that it can tell such fine stories, but rather it has

become language because it has told such fine stories.” ii The meanings ascribed to any piece

of narration may owe to the underlying syntax but the syntax in film is itself a result of its

usage. Many of the formal devices in cinema – like the cut, the dissolve, the 180 degrees

system in the denotation of film space – are the same around the world but this is not to assert

that the ‘grammar’ in cinema is essentially the same across cultures. For instance,

Hollywood, with its causal emphasis on individual motivation may be regarded as

constructing narratives in the active voice while Indian popular cinema with its sense of a

determined universe constructs them in the passive voice iii. Still, such differences do not

come in the way of cultural outsiders comprehending a film and they merely offer themselves

for interpretation – with regard to the dominant cultural tendencies. The utterance itself is

understood but its ‘grammar’ could have one wondering about the utterer’s attitudes, and

therefore his/her milieu and its mores. To illustrate, a Japanese love story will be understood

by someone from India, although its notion of ‘love’ could also make him/her acutely aware

of existing cultural differences.

I have already described Abdrashitov as responding largely to ‘local stimuli’ but serious filmmakers

are not always aware that their concerns are ‘local’ and the ‘local’ is something they

might even wish to transcend. But there are two different implications of the ‘local’ which

come into play here. The first is the socio-political context invoked by the narrative and the

second is the context called into question when a film is being interpreted – given the location

of its discourse. It is evident that the two ‘locals’ are not identical; an animal fable, for

instance, does not specify a context but animal fables from different cultures bear

characteristics that are dissimilar.

The first ‘local’ sometimes does not need elaboration as in films from/about spaces which

have gone through historical processes widely registered – like Germany, Russia and the

socialist world in the 20th Century that a worldwide audience would know about. It is

reasonable to assume that the name ‘Hitler’ need not be explained to film audiences. For

countries where the local context will be unfamiliar to outsider-audiences, film-makers use

other strategies to contextualize issues. The Iranian Asghar Farhadi (A Separation, 2011), for

instance, initially with holds information with regard to the ‘first local’ and then springs it

upon the audience to resolve the mystery deliberately created. If understanding implicates the

local, primarily, the second local should come into play in every kind of film though

identifying it in the art-house cinema from the developed countries is not always easy. One

can be deeply affected by Bergman’s The Silence (1963) without a sense of the ‘second

local’.

The next question is, if location plays such a large part in the meaning of a film, what the

position of the outsider-critic is. As already elaborated upon, cinematic syntax is not local and

an interpreter-critic in film has more freedom than her/his literary counterpart – who works

within the territory demarcated by a language shared with a local readership. The interpretercritic

from outside concerned with what the film means to its intended audience may

therefore overlook obscure cultural references as long as he/she can interpret the film –

however difficult – convincingly. Since filmmakers address audiences by taking the

universality of film syntax as a given, these ‘opaque’ cultural references could be even be

treated as ‘private’ in nature iv. As support to the claims of the cultural outsider, it may be

noted that often, in cinema, astute interpretations come from outside the local culture (e.g. the

French critics on Hollywood), an aspect that does not find an easy parallel in the

interpretation of literary texts, since verbal language has to be learned before one

comprehends literature.

Vadim Abdrashitov as a political film-maker

Abdrashitov and Mindadze’s concerns can be broadly described as ‘political’ in that their

films have generally tried to engage with the notion of citizenship in the USSR and its

attendant issues. There seems to be some agreement that while Abrashitov is not tacitly a

dissident he is still engaged in interrogating the state v . Here is Nancy Condee on his political

position:

“With respect to Abdrashitov-Mindadze’s work ….it is not at the level of social topicality that the

filmmakers choose to engage the audience. Their preoccupations function at a different level,

attempting to construct a set of constitutive metaphors about the absence of cultural practices that

would confirm collective value and differentiate it from the bureaucratic interventions of the state.

Abdrashitov-Mindadze turn to the lability of the human psyche, its eternal availability for

habitation by state desire, the pliable, bureaucratized subject, oblivious both to its institutional

appropriation and to alternative cohesiveness, however unavailable or archaic those ways may

be.” vi

Collective life in the USSR and the pressures upon it may broadly be the theme explored at

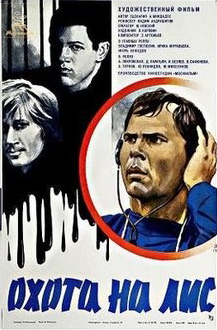

least in the three films this essay is about. The three films are Fox Hunting (Okhota na lis,

1980), Parade of the Planets (Parad Planet, 1984) and Magnetic Storms (Magitnye buri, 2003) and while the first two are set in milieus contemporary to the films, the last has its

action set a decade before the film’s release, in the early 1990s, when state-owned industries

were being privatized and many were usurped by insiders.

The years immediately before and after 1980 were important years for Brezhnev’s Soviet

Union because of the sense of economic stagnation and its discrepancy with the official

pronouncements of the approach of Communism. Krushchev had proclaimed that

Communism would be attained by 1980 and Brezhnev did not repudiate it although 1980 was

near and there was small reason for optimism. What happened instead was the coining of a

term ‘Developed Socialism’ to imply that Communism was on the way, and embarked upon

was the ambitious Baikal-Amur Mainline railway project to cross all of Siberia, stretching

towards the Far East. Towards this mammoth project an enormous number of youth were also

enrolled, youth from a generation that still needed to be brought into the mainstream of the

Soviet Union’s ‘collective life’ vii, as it were. The railway is part of the landscape in many of

Abdrashitov’s films viii and the BAM may be of some pertinence here since it was a national

exhibit.

What we are dealing with when examining Vadim Abdrashitov’s films of the early 1980s is

hence an artist responding to a society which still has a promised utopia ahead, if one slowly

fading away. It should be noted here that Soviet film-makers even during Krushchev’s rule

had faith in the system. While they opposed Stalinism, they did not oppose the socialist state

and the government. While they longed for democracy, they did not resist the totalitarian

utopia under Khrushchev by focusing on the individual instead of the collective ix; the sense

of collective life in the Brezhnev era was apparently still kept feebly alive, if by the state. My

proposition is that ‘collective life’ is the issue at the centre of all three films written about

here.

The films

The three films being examined in this essay are set largely among the working class and deal

with relationships like friendships and marital life. Although Fox Hunting has a single

protagonist the general approach is to deal with communities going through comparable

experiences. There is never a sense, for instance, that what is happening to one person is

specifically his or her own experience; it seems shared by others and this sense of common

experiences among people of a large community or class makes us see evidence of ‘collective

life’ in the films.

Fox Hunting (1980)

The film begins on a summer’s night; a bandaged Victor Belov (Vladimir Gostyukhin) is

taken around in a police car to identify the two youths who assaulted him earlier. This is in a

park area frequented by couples or groups of young people. The first youth who fits the

description tries to flee before he

is apprehended, but he is someone else. The second they

talk to the police know from before. When Victor identifies him as an assailant, they know

where to find the other; the two are apparently familiar figures, Kostya Strizhak and Volodya

Belikov (Igor Nefyodov). is apprehended, but he is someone else. The second they

talk to the police know from before. When Victor identifies him as an assailant, they know

where to find the other; the two are apparently familiar figures, Kostya Strizhak and Volodya

Belikov (Igor Nefyodov).

Victor, when he talks to his friends at the factory the next day, expresses anxiety over how

his injury might affect his ‘training’; we learn later that he plays an organized team game

called ‘Fox Hunting’, resembling a treasure hunt conducted over a vast space with the help of

a radio network. Before the trial Kostya’s mother visits Victor and his family and offers him

incentives to provide the right kind of testimony to help her son. She is well-connected can

get him medical help or books, she says. At the trial Volodya is given a two-year sentence

while Kostya’s similar sentence is suspended. Kostya being better defended seems to have

turned the trial. Victor deduces that Volodya has been punished more than he deserves

because of Kostya.

That is how Abdrashitov and Mindadze set up the drama in Fox Hunting and while the sharp

script works brilliantly well, the narration above does not do full justice to the visual handling

of the exchanges. There are four generations being dealt with here: Volodya and Kostya are

each about 18 years old while Victor belongs to a generation that grew up in the aftermath of

the War. Victor has a son who is around eight or ten and Kostya’s mother – when Victor

refuses her help – declares Victor will have trouble with him, as she has had with Kostya.

She, her wily lawyer and Volodya’s mother (seen briefly at the trial) can be taken to be from

a generation born before the War, and hence with recollection of the Stalin era. Abdrashitov,

who was born in 1945, evidently belongs to Victor’s generation x, one that participates more

innocently in ‘collective life’ than those born a decade earlier, which has learned to play the

system. The difference in the way Victor and Kostya’s parents (who are older) approach

officialdom indicates this. A poster of the 25th Party Congress of 1976 outside Victor’s

factory and the prevailing atmosphere suggests his faith in the political discourse aired in the

period.

The film is showing different generational responses to the grand narrative constructed by the

state but there is still nothing corresponding to the stereotyping of characters in terms of their

degree of faith in the system, as often happens in earlier Soviet films – in which deep political

faith and the absence of it are contrasted (as in Grigori Chukrai’s The Forty-First, 1956).

Abdrashitov’s sensitivity to gestures and body language is incredible and may even be

compared with Eric Rohmer’s. The dissimilarity is that Abdrashitov is not dealing with

atomised individuals but representatives of generations imprinted upon by different historical

experiences.

If the first part of Fox Hunting establishes the relationships between the different generations

and the nation-state, in the second one Victor repeatedly visits the younger man in prison -

without his wife Marina’s knowledge - his politicised generation attempting to bring a

younger one into the ‘national mainstream’, as it were. The first major event is Victor visiting

prison claiming to be Volodya’s relative. Volodya is furious: “He is Belov, I am Belikov;

how are we related?” he asks. Volodya shoos him off and Victor later takes his irritation out

on a young long-haired apprentice in his factory. On his second visit Victor takes along books

(that he has not read) to help ‘improve Volodya’s mind’, but this time he is not allowed in.

When the guard addresses him curtly as ‘mister’ he retorts “You are mister, I am comrade.”

Victor’s secret efforts to connect with Volodya in prison arouse Marina’s wifely suspicions,

that he is having an extramarital relationship and she attempts to ‘win back his love’ by

dressing up!

Victor and Volodya gradually come closer because Victor enrols in a scheme to extend

patronage to a prisoner (as part of his correction), and Volodya rests comfortably in the

private room allowed. It is during conversations here that Victor reveals his satisfaction with

his life after he was ‘fixed’ by military service; he tells Volodya about his family life, his

factory and his prowess at ‘Fox Hunting’. It is uncertain whether ‘Fox Hunting’ is an actual

game but it has the right touch of absurdity to convey the kind of official effort made to

reinforce collective life. In a particularly touching interlude the two watch from their room

window juvenile prisoners playing volleyball, supervised by prison officials. The sequence

might not have drawn attention but Eduard Artemyev’s music infuses it with mysterious

melancholy. The haunting music does not seem inappropriate though little in the narrative is

poignant in itself; parts of it are even comical. Why this is so affecting is difficult to say but

my own drift is that Abdrashitov has contrived to introduce ‘metaphysics’ into the notion of

the generational gap. He conveys the sense that in a country that has gone through so much

unrest within a few decades, generations even ten years apart are divided vertically by their

varying historical experiences and the deliberate erasures of the past due to political

decisions; perhaps they do not even inhabit the same ‘nation’. What we respond emotionally

to here is melancholy at the political state of a country at a moral intersection, rather than

individual destinies.

Parade of Planets (1984)

Abdrashitov and Mindadze’s deep attention to social behaviour does not continue in Parade

of Planets where male bonding is the central motif. The film begins with physicists studying

the skies for a rare

celestial phenomenon, which we eventually learn is an awaited ‘parade of

planets’. One of the protagonists, Kostin (Oleg Borisov), an astrophysicist, returns home that

evening to find a conscription notice waiting: to participate in a periodical military exercise

meant for the reserve forces, with five others he knows from before – a butcher, an architect

and a worker among others. Kostin is senior lieutenant in the platoon while the others are

below him. To cut a long story short their platoon is assigned military exercises but when a

careless soldier is seen by the enemy they find themselves ‘dead’ – a week before the

exercise is to conclude. The six are hence left with free time to explore the surrounding areas

before getting back to their city routine. celestial phenomenon, which we eventually learn is an awaited ‘parade of

planets’. One of the protagonists, Kostin (Oleg Borisov), an astrophysicist, returns home that

evening to find a conscription notice waiting: to participate in a periodical military exercise

meant for the reserve forces, with five others he knows from before – a butcher, an architect

and a worker among others. Kostin is senior lieutenant in the platoon while the others are

below him. To cut a long story short their platoon is assigned military exercises but when a

careless soldier is seen by the enemy they find themselves ‘dead’ – a week before the

exercise is to conclude. The six are hence left with free time to explore the surrounding areas

before getting back to their city routine.

Abdrashitov has described the film as ‘part fantasy’ but this straightforward first part does not

prepare us for what follows. After their group breaks up due to some unthinking behaviour

the six find themselves in a small town entirely of women. There were apparently all-women

textile settlements in the USSR xi but, as Nancy Condee suggests, the film appears to become

irrational and metaphorical here. The segment dealing with the first realization of the men

with the peculiarity of the space is stunningly realized. The edges of the frames are in soft

focus and we are given captivating close-ups of feminine faces marked by a kind of

preoccupied sadness. The only male presence is a mannequin in a tailor’s window. We see a

variety of faces quick succession and the enchantment inherent in the gaze makes it evident

that it is male. At the same time there is no sign that the women are aware they are being

studied by the men. Later at a dance the men start conversations with some women; one of

them admits he was addicted to drink - as her former husband also was - and another that he

is actually a ‘ghost’ since he died by an artillery shell. The woman dancing with Kostin

appears deeply affected.

The segment does not yield to immediate interpretation but we retain its impact. It is faintly

reminiscent of a dance sequence in Yuri Norstein’s animation film Tale of Tales (1979), in

which the male partners are snatched away as war breaks out and women dance alone. Later

that night the women follow the men to the river and they swim there. On the soundtrack we

hear Beethoven’s 7th symphony (2nd movement), dedicated to fallen soldiers xii. But suddenly,

as they swim, the men abruptly decide to move on and they leave the women behind. The girl

with Kostin wants to come along but he asks, “Where to? What for? There is nothing there.”

When the girl insists she will drown because of him, he tells her unmindfully to swim back. It

is as though the men know they have no place here but must move on: they are driven by

some impulse.

On the shore the men sit around a campfire discussing their lives, sometimes exchanging

barbs even as they acknowledge that this is their last meeting. They will not be recalled for

another military exercise since they are growing old and they have not even met since the last

time. This is a deeply moving segment because of something unexpected that happens. An

airplane flies overhead and the men look up. Abrashitov cuts briefly to the inside of the

airplane; the passengers are all asleep. It is difficult to say what this is about but we are

reminded of a gap between the men as they are now and the social world that they have left

as ‘ghosts’. There is also a sense that they are reflecting on something the ‘living’ are

sleeping through.

The next morning, as the group needs to cross the river again, they encounter a camper with a

boat who reveals – on acerbic questioning – that he is an organic chemist. There is a sense of

hostility exhibited by the men that Kostin tries to take a distance from; one gathers that

Abdrashitov is referring here to a distrust of the intelligentsia among the working class,

although one cannot be certain. In an earlier sequence, a soldier asks Kostin if he is not a

physicist and Kostin tries to play it down with a vague reply. In any case, the chemist rows

them from the island to the mainland for another strange encounter before they return to the

city.

On the mainland, the group, now joined by the chemist, pass through a wooded area in which

they find themselves watched by elderly people who seem, from their clothes, to be from

another era, and some of them greet the men. One of them accosts Kostin, addressing him

repeatedly as ‘Fedia’, taking him for her son. Kostin excuses himself but she follows him

obstinately. The men discover through a functionary that they are in a retirement home for the

aged where guests are rare, so rare that when they walk out of its office the elderly residents

surround them and stare. On woman doctor’s plea Kostin agrees to become ‘Fedia’ for the

old woman. She lost Fedia at the time of the blockage of Leningrad by the Germans, and her

daughter as well. Gradually, Kostin opens out and reveals his generally dejected state. He is

an astronomer but there is nothing new to discover. He does not talk much because

‘everything has already been talked about and everything is already clear.’ This again is a

deeply affecting sequence, not least because of Oleg Borisov as Kostin, with no expectations

from life. When Kostin goes out later he finds the old people all looking up at the sky for the

‘Parade of Planets’ which one of his companions has told them about. There is nothing to see

since the phenomenon does not reveal itself to the naked eye, but rousing music accompanies

their expectant gazes. Kostin has what appears to be a vision of the heavens as seen through a

telescope.

Parade of Planets is a difficult film to write about and, describing it as I have done is simply

the first step before one admits that making complete sense of it is impossible. It is deeply

pessimistic although it posits no socio-political issues that might justify it. But there is a

palpable sense of dramatic expectations of some kind – with a celestial phenomenon as

metaphor – coming to very little. That the film is political in its import there appears to be

little doubt. I take Kostin’s despondent reply to his ‘mother’ that he does not talk since

‘everything has been talked about and everything is clear’ to imply the political certainties of

the Soviet era wearing thin, leaving the public with ‘expectations’, but of god-knows-what.

At one time the ‘Parade of Planets’ might have meant the arrival of Communism, but even

that is uncertain now. ‘Everything has been talked about and everything is clear’ carries very

much the same implication as Victor (in Fox Hunting) telling Volodya that ‘everything is

fine’, but one cannot help catching the difference in tone between 1980 and 1984. The latter

year, one recollects – without much pertinence – is the year to which Aleksei Balabanov’s

horrific Cargo 200 (2007) also pertains. Perhaps Abdrashitov and Mindadze are dealing

metaphorically with a situation Balabanov dealt with viscerally, since they worked under

censorship.

Magnetic Storms (2003)

There are references to family life in both Fox Hunting and Parade of Planets and there is a

sense of marital ties gradually weakening under socialism. Victor’s son Valera exhibits a

degree of ‘oedipal’

hostility towards him in Fox Hunting that portends Victor’s own future

troubles with the next generation. Parade of Planets deals only with bonding between males

but the talk around the campfire suggests acrimonious or none-too-happy family

relationships. hostility towards him in Fox Hunting that portends Victor’s own future

troubles with the next generation. Parade of Planets deals only with bonding between males

but the talk around the campfire suggests acrimonious or none-too-happy family

relationships.

The family’s trajectory has found reflection in films dealing with the institution of marriage,

and its portrayal usually implies political discourse. The endorsing of ‘true love’ by Moscow

Does not Believe in Tears (1980), which also won the Best Foreign Film Oscar and found

favour in Hollywood, is an indication of its conservative viewpoint. The representation of the

family is emblematic of the condition the nation-state is perceived to be in; its bleak picturing

in Zvyagintsev’s Loveless (2017) can hence be understood as political critique. Politics also

manifests itself in the domestic space in Magnetic Storms and ‘love’ is shown as

compromised.

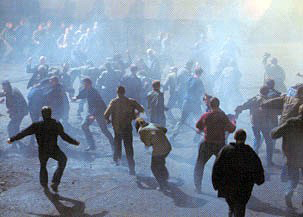

Magnetic Storms is a curious film – with perhaps even more left unspoken than in Parade of

Planets. The film begins at night, two groups battling out in an industrial area. The men

advance pugnaciously towards each other; the protagonist, upon whom the camera focuses, is

in one of the groups. The scene is lit harshly from above and each man is illuminated as if

separately. The men are dressed roughly alike but it is revealed that the groups are fighting on

behalf of two bosses Markin and Savchuk. The protagonist Valera identifies himself with

Markin and he is beaten up by Savchuk’s men but it turns out he is actually with Savchuk.

The two groups storm the local factory from its two opposite gates and after some more

fighting Valera leaves limping for home, the modest apartment he has lived in with his wife

Marina.

In the apartment he discovers that he has lost his wedding ring in the scuffle. Later, some

friends try to take shelter but they are pursued, beaten up and the apartment is left in

shambles. Marina’s wedding ring which had been placed on the table is not to be found. The

chicken Valera has been eating – a precious commodity – is also missing. Later, Marina’s

sister Natakha, who has been expected from Moscow, drops in. She has apparently dyed her

hair dark and she explains it was because ‘the others were blonde’. She expresses concern at

Marina’s paleness and appearance, accuses Valera of making her unhappy, which Marina

denies. Natakha is staying at the local hotel and appears well off; she leaves after expressing

alarm at the disturbed condition of their apartment. Marina and Valera are to meet her next

day at her hotel.

The next day Marina and Valera try to harvest potatoes from a field illegally, with some

others. Even the passing of a vehicle on the highway has the potato pickers taking cover

among the shrubs. On the train with their sack of potatoes Valera is recognized from the

factory and thrown over by someone from the opposite camp. Marina follows him, hurtling

down an embankment but only slightly hurt. They meet Stepan, a hunter with a gun and an

old acquaintance. As they talk they hear an engine and Marina comes running frantically

followed by an armoured vehicle which fires at something in the distance. The three go out

to eat at a restaurant but, abruptly, Valera begins shouting at two well-dressed men in suits

who pay up and leave quickly, apparently ignoring him. They are Savchuk and Markin,

making peace privately.

Stepan has paid for the meal and says he has been profligate; he has sold his gun to pay for

the meal and mentions splurging in the local hotel on a ‘dark-haired whore’. Before leaving

he quietly makes over Valera’s wedding ring from the skirmish of the night before and

declines to answer questions. As Valera and Marina stand outside a wagon comes by, picks

up Valera for some more street fighting. Marina is waiting when he returns; she is evidently

distraught. The two meet Natakha later at the hotel. Marina’s sister is made up and

overdressed; she shows concern that her little sister has a cut on her face that might leave a

scar. Their conduct at the table is difficult to comprehend entirely: husband and wife decline

to eat the food they are offered; something is said that reduces Natakha to tears but they are

all laughing a few moments later; Marina wonders if she should dye her hair black; Valera

persuades Marina to take the money Natakha offers them. Natakha apparently does not see

much good coming to Marina from Valera though she wants both to join her at the train

station at an appointed time, a day later.

Abdrashitov lays out the action directly without a clue as to its setting and, if someone has

not been told, it takes a while before he or she catches a sense of Magnetic Storms . Details

such as Natakha’s doings, that she has been successful as a prostitute in Moscow and sees

that life as the best one for her sister are not immediately discernable. The other two films are

set in times contemporary to each film’s making, which makes ‘contextualizing’ them

unnecessary, but doing the same thing when the action takes place ten years before needs

speculating about.

My own sense is that Abdrashitov and Mindadze are being true to politics in the USSR (and

Russia) being opaque. To be true to individual experiences it would also be necessary to

convey their impenetrability: causes and effects cannot be clearly enumerated since social life

itself did not make them clear. Perhaps ‘contextualizing’ the narrative by naming the year of

the action would have provided an explanation of some sort. One may now be aware of what

happened in the Yeltsin era, but not only were Soviet citizens not aware then, they had also

become habituated to not knowing or inquiring. The stripping events of explanations is a

strategy other Russian filmmakers like Aleksei German have followed and films like

Khrustalyov, My Car! (1998) have mystified foreign audiences. Someone who has gone

through the experiences detailed, or has learned of them, would recognise what is portrayed

immediately. But ferreting out information about how life proceeded (and why) in the early

1990s privileges the spectator with more understanding than the participants might have had,

perhaps makes it untrue.

In the last part of the film Marina and Valera are once again caught up in a skirmish and

separated. Valera has his hands clamped on the factory floor by a former ‘comrade’ until he

is mysteriously set free by someone, who turns out to be a woman. There is unrest in the area

and armoured vehicles are about firing at random, but the strange woman follows him. When

he reaches the station at the appointed time it is too late for him to do anything to change the

course of events. Marina is embarking for Moscow on a train, her hair dyed black; the train

commences to move and she weeps. There is little Valera can do except return home, to the

strange woman waiting for him, wearing Marina’s ring that she has found. She is a crane

operator and has been watching Valera although he has never seen her. The next morning

there is an open reconciliation between Savchuk and Markin and everyone is a ‘friend’ once

more at the factory. Stepan attempts to make a speech but is arrested and led away. That night

Stepan escapes and tries to take shelter with Valera but he is pursued and killed. The film

concludes next morning with Valera and the woman walking to work. She still wears the

ring since Valera has permitted her to; Marina is not coming back. The woman’s name is

Tatiana and when Valera is restless she asks if anything is the matter. “Everything’s fine” he

replies.

Magnetic Storms is a more disturbing film than the other two written about and an aspect that

could strike the spectator is how the narrative has moved down the social scale - to deal with

working class characters without the awareness that marked the protagonists of the other two

films. Kostin from Parade of Planets was from the intelligentsia but even Victor in Fox

Hunting had a greater sense of society than do Valera and Marina, who are like children.

Stepan, who takes the position of a ‘rebel’ in the narrative, acts as if whimsically and without

a plan.

This lack of political awareness is shown to go hand in hand with the manipulation of the

workers by the managers of the factory. When Valera discovers private dealings between

Savchuk and Markin, he still returns to fight without questions. The friend who played the

accordion at Valera’s wedding, clamps the latter’s two hands down now with vices because

of rivalry between their bosses. In the harshly lit night sequences where the fighting happens,

the film makes few distinctions between participants; it is as though they were all ‘fodder’ for

economic forces. Valera must have guessed that Natakha is a prostitute but he does little to

protect Marina. Marina and he love each other but ‘love’ appears like the attachments

domesticated animals might exhibit; Valera does little to show he cares enough to act on her

behalf.

The family is weakening in Magnetic Storms but on account of people themselves having

become enervated, easy to manipulate through the smallest inducements. Rather than portray

the sad fates of moral people undone by historical circumstances, the film offers us a chilling

picture of the disempowered working class in the terminal stages of a ‘worker’s state’ xiii.

Valera’s ‘everything is fine’ to Tatiana is not ironic and does not invite disbelief: those could

be his feelings since he knows no better. Valera could be Volodya from Fox Hunting xiv, fully

an adult but not wiser. If ‘collective life’ is not synonymous with being herded together, that

is what it is to the citizenry.

Conclusion

It is difficult to tell from the three films written about what Abdrashitov’s actual position is

with regard to the Soviet state. He worked under censorship but there is little evidence of

satire even in the most comical bits of Fox Hunting. Victor Belov’s exertions on behalf of

Volodya Belikov do not appear ill-motivated though he only makes friends with Volodya

without bringing him into the ‘mainstream’; he probably remains a hooligan since he keeps

the same company. Between Fox Hunting and Parade of Planets Abdrashitov has become

less sympathetic to the working class and the decline in his sympathies is sharper with Magnetic Storms .

There is a stifled sense in Parade of Planets that workers are resentful of the intelligentsia xv.

One detects a sensitivity gap between Kostin and the others that brings it out although,

nominally, all of them are equal as ‘ghosts’. Kostin’s silence seems also associated with the

likely incomprehension of his words by the others. At the conclusion Kostin and the organic

chemist seem to distance themselves from the others who are shouting each other’s

nicknames, and the last frame shows Kostin wondering privately. Nancy Condee notes how

little the characters are involved with each other when they part xvi, suggesting that solidarity

within the class is a mythical construct encouraged by the state and this is also consistent with

what is shown in Magnetic Storms . Perhaps Abdrashitov’s position is that of an intellectual

whose initial belief in the system has been steadily undermined over the decades but there is

little else to replace it - other than filmmaking!

Given these descriptions, the reader may wonder what Abdrashitov and Mindadze are

holding up in the films. If class solidarity is not eulogized neither is there a family ideal; that

Victor withholds information about visiting Volodya from his wife indicates his lack of

confidence that she will understand him, and the same sentiments – about wifely

misunderstanding – are echoed around the campfire by the men in Parade of Planets xvii. But

the journey of the ‘ghosts’ through a space brought alive by implicit references to the War

gives us a clue. Victor in Fox Hunting also admits that he was like Volodya till he was ‘fixed’

by the army. What deserves greatest respect to the director is apparently the solidarity of the

Russian people in the War, and nationhood is intimately tied up with to their experiences

together. As each generation grows more distant from these memories holding them together

as a community, the more fragmented the nation is, is his implication and this fragmentation

manifests itself as a generation gap in both Fox Hunting ( Victor and Volodya) and Parade of

Planets (Kostin and the old woman). Magnetic Storms deals with a generation to which war

means nothing at all, which accounts for its lack of cohesiveness. Military service removes

class distinctions at least temporarily and only as soldiers are men together. The general

exclusion of women from the military may play some part in the way Abdrashitov regards

them xviii.

When dealing with artists whose work is as ambitious, complex and intriguing as Abrashitov

and Mindadze’s, any label attached to their values – like ‘humanist’, ’nationalist’, ‘leftradical’

or ‘democratic’ can only be reductionist in an extreme sense. Still, one might propose

that what drives them is not a belief in Marxism or democratic values as much as a yearning

after solidarity in nationhood, and their looking to the military as an ideal suggests it. The

acceptance received by their films not being high during Perestroika was perhaps because the

sentiment was not in great demand at the time. In that respect their work may be called

‘patriotic’ although it is a different kind of ‘patriotic’ cinema than what the USSR was

generally known for.

Notes/References:

| I. |

David Bordwell posits four different kinds of meaning that may be constructed out of any film; the

fourth or last is the meaning which goes beyond what the film ‘knows it is doing’, i.e. it is the

repressed or symptomatic meaning. In interpreting Abdrashitov, I am avoiding this last kind of

seeking after meaning, i.e.: eschewing what is generally termed ‘deep reading’. See Bordwell, David:

Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,

1989, 8-9.

|

| II. |

Metz, Christian: Film Language: A Semiotics of the Cinema, Trans. Michael Taylor, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990, 47.

|

| III. |

Raghavendra, MK: Seduced by the Familiar: Narration and Meaning in Indian Popular Cinema, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008, 45-6.

|

| IV. |

To use an analogy, would not a portrait, apart from respecting the conventions of portrait painting

which are understood by a public, also share something privately with the sitter? It may be proposed

that all art – including cinema – will include elements which do not benefit by interpretation because

they are not addressed except privately.

|

| V. |

Their ambivalence seems to have worked to their detriment after Perestroika when those who were

clearly dissidents evoked more interest both inside Russia and internationally. Condee, Nancy: The

Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema, New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, 155-6.

|

| VI. |

Ibid, 142

|

| VII. |

Ward, Christopher J, Brezhnev’s Folly: The Building of BAM and Late soviet Socialism, Pittsburgh,

PA: The University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009, 1-12.

|

| VIII. |

Condee, Nancy: The Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema, 152.

|

| IX. |

Timofeevsky, Alexander, The Last Romantics, from Michael Brashinsky, Andrew Horton (eds.)

Russian Critics on the Cinema of Glasnost, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 25-6.

|

| X. |

In a conversation with Volodya, Victor also reveals that he was born in 1945.

|

| XI. |

Condee, Nancy: The Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema, p 145.

|

| XII. |

In Beethoven’s address at its premiere these motives were named: "We are moved by nothing but pure patriotism and the joyful sacrifice of our powers for those who have sacrificed so much for us." Quoted in Goldschmidt, Harry: Beethoven -Werkeinführungen, Leipzig: Reclam, 1975, 49.

|

| XIII. |

There is an ironic comment that a ‘friend’ makes when he sees Valera’s hands clamped down: “the proletariat fettered.” That gives us some sense of what Abdrashitov is getting at. The ‘friend’ does not set Valera free.

|

| XIV. |

Victor’s son was called Valera in Fox Hunting. Nancy Condee notes the repetition of certain names in Abdrashitov and Mindadze’s oeuvre. This could be to convey social archetypes and their trajectory during the history of the USSR. See Condee, Nancy: The Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema, 150-1.

|

| XV. |

The gulf between the working class and the intelligentsia is also explored by Andrei Zvyagintsev in Elena (2011), in which perhaps the director’s sympathies are aligned as Abdrashitov and Mindadze’s are here.

|

| XVI. |

Condee, Nancy: The Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema, p 153.Condee also draws our attention to four from the group abandoning the other two before encountering them in the ‘city of women.’

|

| XVII. |

As a contrast it would be difficult to conceive of a Hollywood film about male bonding (e.g.: a war film) in which each of the men does not recall his wife or girlfriend except fondly. An unpleasant memory is usually treated as an exception that a future relationship erases.

|

| XVIII. |

The marginalization of women in the narrative is a feature of much of Russian cinema – Tarkovsky, Balabanov and Aleksei German included.

|

MK Raghavendra is The Founder-Editor of Phalanx.

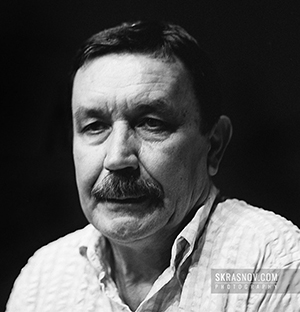

Courtesy: vadim-abdrashitov-film-director

Courtesy: parad-planet

Courtesy: Fox_Hunting_(film)

Courtesy: Magnetic Storms

|

|

|

|

|

|

Top |

|

|

|

|

|