|

Introduction Introduction

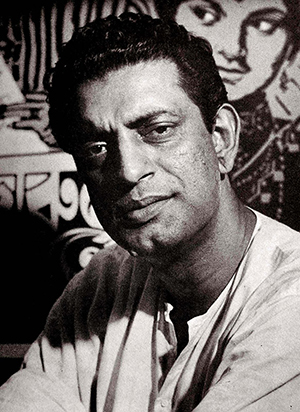

Satyajit Ray is India’s most important film-maker and many of his works have defined the norms

for Indian cinema. Among the aspects his films have dealt with an important one is the position

of women in Indian society. This is an examination of only one recurring representation in his

films.

Of Ray’s women and Aranyer Din Ratri in particular Chidananda Dasgupta said, “…the women

are distinctly more real than the men.” i Darius Cooper clubs the two leading intellectuals of

Bengali culture Tagore and Ray together and argues that the two have “been seriously concerned

with the constricted roles that Indian women have had to play on Indian society in general and in

Bengal in particular. Both have depicted with extraordinary clarity and empathy women’s

isolated and self-denying status in a male dominated system.” ii He states, “…there are those like

Satyajit Ray who give their women voices of their own in an effort to make them distinct, unique

and triumphant in this all-encompassing process of becoming.” iii

Ray’s women characters certainly stand out; on a closer examination the following are some

categories to emerge conspicuously in his films: matriarch in Pather Panchali, young wife in

traditional patriarchal society in Devi and Mahanagar, young romantic souls in Apur Sansar and

Kanchanjunga, unfulfilled women as in Charulata and Ghare Baire and the thinking, articulate

woman as played by the mature Sharmila Tagore in Nayak, Aranyer Din Ratri and

Seemabaddha. Most of Ray’s works are derived from Bengali literature and are adaptations.

However, in contrast to their representation in the novels, many of the women etched out by Ray

in his films are stronger and bolder characters who manage to balance both the ghar and the

baire. In a world riddled with crises of various kinds, they emerge creditably.

The two actresses with whom Ray worked with again and again in his films were Madhabi

Mukherjee and Sharmila Tagore. Madhabi was a successful commercial film artist before she

starred in Mahanagar (1963). She was also cast as the eponymous heroine in Charulata (1964).

As Arati in Mahanagar she played the role of an upright woman who confronts her superior

when her friend and colleague Edith is fired because of upper-caste prejudices. Shortly thereafter

she played Karuna in Mahapurush in 1965. Sharmila Tagore began working with Ray as early as

1959 in Apur Sansar when she was 13. Subsequently she went on to play the roles of Aparna in

Aranyer Din Ratri (1969), a much feted film in Ray’s oeuvre, and Tutul in Seemabaddha (1971).

Considering their use in the films one senses that the roles drawn up for these two actresses were

based on Ray’s view of women; perhaps they were able to bring out the nuances of the

womanhood Ray had in mind.

It is interesting that only in Ray’s cinema does Sharmila Tagore play strong women characters,

whereas she has mostly been playing romantic roles in commercial cinema. The characters

played by Sharmila in Ray’s films are not ‘individuals’ in the full sense and it may be incorrect

to praise her performances for their delineation of character and it might be more appropriate to

look at her presence as a moral signpost, as it were. Ray was able to use the mature Sharmila

persona in these films not to take the position of a protagonist but to act as a foil to a man at the

moral crossroads, to guide him along or make him see his circumstances more clearly. It is the

role of the strong woman as guide or catalyst present in the three key films that is examined in

this paper.

Aditi in Nayak (1966)

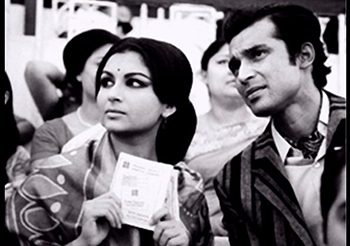

In Nayak, Ray turns to the world of cinema and cine idols, for which he got Uttam Kumar, a real

life Bengali star to play a fictional matinee idol named Arindam Mukherjee. Most of the film

unfolds

through Arindam’s journey from Calcutta to New Delhi aboard a train where he

encounters Aditi Sengupta played by Shamila Tagore, a serious minded journalist who, in

conversation with Arindam, is able to draw out his anxieties and doubts. The film may have a

limited parallel in Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957) in which also a personage is

travelling to receive a prize, his inner journey paralleling the outer one. The central thread of the

film is the relationship between Arindam and Aditi or, rather, the exchanges that make the film

star move towards self-discovery. through Arindam’s journey from Calcutta to New Delhi aboard a train where he

encounters Aditi Sengupta played by Shamila Tagore, a serious minded journalist who, in

conversation with Arindam, is able to draw out his anxieties and doubts. The film may have a

limited parallel in Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957) in which also a personage is

travelling to receive a prize, his inner journey paralleling the outer one. The central thread of the

film is the relationship between Arindam and Aditi or, rather, the exchanges that make the film

star move towards self-discovery.

The bespectacled Aditi is put across from the beginning of the film as a thinking woman in her

own right, who along with two others runs a magazine for women called ‘Adhunika’ or ‘The

Modern Woman’ as she informs her travelling companions - a young husband and wife. A pen

clipped to her blouse, with no trace of make-up and square glasses lends Aditi a thoughtful

appearance. Aditi has the air of someone who relies heavily on her capacity to articulate rather

than her good looks. Her appeal is largely intellectual, though as Arindam is to find out later that

it is not without allure.

Although her charm fails to rub off on Arindam initially, nevertheless it does appeal to him

eventually when he catches her off guard without her glasses, “Wow! You do look nice without

your spectacles,” at which she quickly puts them back on again. The pen becomes an important

and even distinguishing visual marker which even Arindam notices and which he reiterates while

instructing the train attendant to call Aditi at the dead of night. With the glasses on, she is Ms

Aditi Sengupta, editor of Adhunika or ‘The Modern Woman’ but without her glasses she is

Aditi, another pretty face. Even though Aditi tries to draw a line between their two worlds – that

of Arindam and hers, a discerning reader of the film text will not fail to notice that the two are

not unalike in being guarded and only gradually allowing others see them for what they are.

Aditi, who first comes across as a very confident and independent woman who can be blunt to a

fault, reveals her considerate and sensitive nature when she refuses to cash in on the intimate

inputs that Arindam gives her about himself, which she might have used to further her own ends

by publishing and enhancing not only the appeal of her serious minded women’s magazine but

also its sales.

It is necessary to point out here that she holds Arindam in some contempt for his films and for

his career and later in her interaction with him it is confirmed, but from what we see in

flashback. But as the film continues we gradually get the sense that she is not a ‘person’ in the

accepted sense but a moral agent who is not so much flesh and blood as exemplar. In fact, one

may see deliberation in a parallel with another woman here – Molly Sarkar who is also travelling

on the same train. She is an ambitious and attractive young lady whose husband is intent on

capitalizing on her good looks to mobilize business for his advertising company from a rich

businessman Haren Bose – travelling with his family as their co-passengers. While Molly Sarkar

is reluctant at first, in effect quite disgusted with the proposal of ‘enticing’ Mr. Bose, she decides

pragmatically to use the opportunity to strike a deal with her husband to let her work in films, as

compensation.

What is particularly significant here in Nayak is the way Ray chooses to portray his other women

characters, always in stark contrast to Aditi. In a flashback we see Arindam’s co-star Pramila

coming to visit Arindam in the dead of night to request him to help her get into movies as it is

difficult for newcomers to gain an entry. But what could have been done in the morning is

attempted by the lady in the night hinting at the fact that she is ready to give more in return for

Arindam’s favor than meets the eye. Aditi constructed differently, acting as a contrasting figure

to not only Pramila but all the other women present in the narrative. Arindam is startled to find

this third kind who neither wants anything nor worships him but is capable of scrutinizing him,

as it were. She is the active agent who with her questions provokes his subsequent introspections

in the film, presenting a clear contrast to the other secondary women who seem the prevailing

‘standard’. Although Arindam’s conduct does not suggest desire for her in the course of the film

there is still a certain chemistry which develops between the two, which makes the audience

unconsciously pair them off. Perhaps she would have been an ideal wife for him is one’s

immediate thought.

A key motif in the film is Arindam’s alcoholism and it is his reflection in a broken mirror at a

drunken moment that prompts him to contemplate suicide - although Aditi arrives in the nick of

time and as he hangs drunkenly out of the swaying train. He has packed a bottle in his bag and it

is in one of his drunken moments that he decides to take his own life after he has confessed it all.

There is little doubt here that Arindam is weak and Ray is using alcohol as a trope to imply

moral weakness (in men). Earlier we were made privy to many of his misdoings – his

involvement in some kind of a brawl where Pramila’s husband accuses him of taking advantage

of his wife. He has also betrayed people – Shankar da, his acting guru and his friend Biresh, and

he did not help the aged Mukunda Lahiri, a mentor in decline. Perhaps Arindam is escaping his

fallibilities through liquor. In contrast Aditi is the ideal woman in a gathering of women who are

weak too – either morally (Pramila) or are under male domination (Mrs Bose, Molly Sarkar). In

summary we could say that Aditi is the ideal wife Arindam may have missed, someone who

might have cured him of his weaknesses in a world where women are generally as weak as men -

since most of them are only too eager to submit to them or take advantage of patriarchal social

mores.

Tutul in Seemabaddha (1971)

By Ray’s own phrasing Seemabaddha (1971) adapted from Shankar’s novel by the same name is

the story of ‘boxwallahs’ - the western oriented commercial community in Calcutta of the 70s

who worked

in large companies and whose lives revolved around work, cocktail parties, clubs

and race tracks. At the heart of Seemabaddha is Shyamalendu Chatterjee, the protagonist of the

film. He is the author’s/ director’s subject of interest and his life as an executive is the prime

focus of Seemabaddha. Essentially a decent though ambitious man, Shyamalendu’s life takes a

turn when the consignment of fans to be exported to Iraq and for which he is responsible turns

out defective. The company faces the possibility of not only losing face but paying a large fine in

accordance with the clauses in the contract and Shyamalendu resorts to unethical means to sort

out the problem. in large companies and whose lives revolved around work, cocktail parties, clubs

and race tracks. At the heart of Seemabaddha is Shyamalendu Chatterjee, the protagonist of the

film. He is the author’s/ director’s subject of interest and his life as an executive is the prime

focus of Seemabaddha. Essentially a decent though ambitious man, Shyamalendu’s life takes a

turn when the consignment of fans to be exported to Iraq and for which he is responsible turns

out defective. The company faces the possibility of not only losing face but paying a large fine in

accordance with the clauses in the contract and Shyamalendu resorts to unethical means to sort

out the problem.

When the film commences we are given a summary of Shyamalendu’s career with a voiceover.

He was the son of a school teacher and a good student who stood first in his postgraduate exam

in English and was considered a model student. There is an ironic commentary added here in that

as soon as he is employed as an executive he acquires a wife, the daughter of his teacher. There

is a point made here about his wife Dolon being a ‘possession’ of sorts since she goes along with

financial wherewithal.

Immediately after this introduction we are introduced to Shyamalendu’s sister-in-law Tutul

(Sharmila Tagore) who has arrived on a visit. In a series of shots in the car in which they travel

home from the station we are made to observe Tutul’s conduct. Tutul is a contrast to her sister

Dolon; she is both beautiful and graceful but has more intelligence, revealed in a bantering

session where she engages in with her brother-in-law. Shyamalendu who neither engages in any

kind of conversation with Dolon nor shares any intellectual tastes with her seems stimulated in

Tutul’s presence.

In Seemabaddha, Ray presents Shyamalendu’s sister-in-law as a contrasting moral polarity to

Shyamalendu who has chosen to leave behind qualms when jockeying furiously up the corporate

ladder. Tutul brings with her the uprightness that might have been Shyamalendu’s, had he

decided to lead a life of the mind instead of opting for that of an ambitious executive with an

expense account. Tutul’s wordlessness, her desire not to pass judgments without adequate

observation, her intelligence and her quiet determination to stick to what she believes and the

choices that she makes both in the onscreen spaces as well as the off-screen ones (her boyfriend

or fiancé is a Naxalite, who perhaps reminds her of the Shyamalendu of the past), makes her a

distinctive woman character in Ray’s oeuvre, perhaps in tune with the times when ‘political

commitment’ was demanded of the artist in Bengal. If one were to compare Shyamalendu to her

we might say that he has taken the path to success that the times frowned upon while she has

stuck sternly to moral choices.

Ray sets up Dolon as a contrast to Tutul – Dolon hardly thinks before she makes utterances,

whereas Tutul is reflective. In fact, during the course of the film she hardly speaks; she is more

intent on observing. After Tutul has been shown around the Chatterjees’ flat by her sister, she

says, “You’ll are leading a very comfortable life, aren’t you Didi?” Dolon (who does not catch

the irony) fails to ask if Tutul may want something else from life. Tutul is literary minded,

knowledgeable with a keen interest in things that Dolon is not aware of. She is curious about

things; she absorbs what she sees or hears that might add to her awareness without being prudish.

In the racecourse with her brother-in-law she picks up the dominant style of betting and wearing

goggles, even winning nineteen rupees.

When Shyamalendu’s parents arrive unannounced one evening in the midst of a cocktail party,

the husband-wife duo of Shyamalendu and Dolon take turns to leave the party to converse with

them but Tutul who belongs to old school, believing in keeping her values intact, volunteers to

sit with her brother-in-law’s elderly parents and keep them company. The introduction of alcohol

as an integral part of corporate life is significant here if we consider the way it was used in

Nayak, where it becomes a way of showing Arindam’s weakness.

The next morning, while Dolon sleeps, Shyamalendu plays out a little drama of flirtation with

Tutul. Tutul seems uncomfortable with his attention. In a close mid-shot the camera catches

Shyamalendu gazing at Tutul which clearly bespeaks of her attraction for him. Tutul, it seems, is

aware of it and this knowledge makes her uncomfortable. We are made complicit to the fact that

Shyamalendu had come to harbor some feelings for his sister-in-law, though they are ‘illicit’.

Shyamalendu who surprisingly seeks approval from her, shows her the boardroom in the office.

Tutul immediately wonders at why until Shyamalendu confesses that it is a dream destination for

him. He is naively revealing his innermost ambitions without suspecting that he falls in her

esteem through them.

When Shyamalendu takes his family to dinner to celebrate the success of his plan at his

workplace (unknown to his family), a colleague Runu Sanyal who is at the restaurant begins

enquiring about the trouble in Shyamalendu’s factory— and the camera now focuses on Tutul.

While the two men talk, emotions flit across Tutul’s face. As the conversation continues it is not

hard for Tutul to comprehend not only the shameful reality of the situation but that of her

brother-in-law as well. The next day when a jubilant Shyamalendu comes home after being made

an Additional Director, his wife duly shares his excitement. Tutul however remains cold; she

does not sit with them at this triumph but instead stands aloof at the window humming a tune and

then, as if reluctantly, sits down with them. As she gazes at Shyamalendu, he suddenly begins to

look afraid—it is as if the wordless gaze Tutul is fixing on him is one of derision. When she

continues to sit there wordlessly, he knows that he has failed in her eyes and that her grasp of his

unworthy self is complete.

Tutul is delicately placed in the story in relation to the male protagonist in that she is an object of

desire for him but also an intellectual rival. When she says that she has studied psychology and a

whole lot of other things and her remarks imply reading and education, Shyamalendu quickly

retorts, “Fortunately, it will be difficult for anybody to decipher that.” Since she returns his

feelings (as least as he was) his moral fall in her eyes is much more than ‘moral judgment’. If

Aditi felt nothing for Arindam but had an impact upon him in Nayak Tutul feels something for

Shyamalendu – but as he was instead of what he has become. Since her Naxalite boyfriend is not

brought up it is Shyamalendu (as he was) that she might have chosen, if she could have still

made that choice. In this film again Ray uses the same tropes from Nayak – a weak man meeting

an intelligent woman who makes him come to face with his own moral weakness at the height of

his success. As in the other film there is alcohol in attendance and a contrasting, shallow

feminine character, to the one played by Sharmila.

Aparna in Aranyer Din Ratri (1970)

Aranyer Din Ratri is about four urbane young men who take a short holiday in Palamau. They

travel in the protagonist’s car and Ashim is the most accomplished of the four. In Palamau they

attempt to live

out a free existence through conduct they might have been made aghast by in

everyday life - and return home chastised. The story begins when they meet a Bengali family and

befriend the two ladies in it – the beautiful, petite Aparna and the widowed daughter- in-law

Jaya. Ashim is drawn to Aparna and receives some transformatory lessons from her; Hari (Samit

Bhanja) has a relationship with a tribal girl (Simi Garewal) while Sanjoy (Subhendu Chatterjee),

who receives Jaya’s advances, responds with trepidation. Sekhar (played by comedian Robi

Ghosh) remains unchanged. out a free existence through conduct they might have been made aghast by in

everyday life - and return home chastised. The story begins when they meet a Bengali family and

befriend the two ladies in it – the beautiful, petite Aparna and the widowed daughter- in-law

Jaya. Ashim is drawn to Aparna and receives some transformatory lessons from her; Hari (Samit

Bhanja) has a relationship with a tribal girl (Simi Garewal) while Sanjoy (Subhendu Chatterjee),

who receives Jaya’s advances, responds with trepidation. Sekhar (played by comedian Robi

Ghosh) remains unchanged.

Beginning with Aparna, her appearance belies the depth of her character - she is stylish, speaks

very little, a characteristic people might associate with shyness or arrogance. In contrast to her is

her widowed sister-in-law Jaya who has a young son. Jaya is ‘bigger built, with large features

and a sexy languor about her’ iv (Dasgupta 1992: 95). She is drawn to the tall, laconic Sanjoy who

thoughtlessly goes along with her until he is pulled up short - when she simply offers herself

when they are alone.

Aparna escorts Ashim to her quarters which is some distance from the main house and promises

to be a haven for the meditative and serious minded – which Aparna is. Ashim is taken aback by

her collection of books and music – and he is quick to figure out that she is unlike most other

women he has met or impressed. If he finds it difficult to characterize Aparna on their first

meeting, she defies it for the entire length of the narrative. Aparna is not given to instructive

speeches and refrains from commenting on Ashim and his friends when she and Joya catch them

unawares at the well - stripped to their underpants or drunk performing the ‘tribal twist’ on a

forest road. Aparna is observant, quick at gauging character, spots Ashim as egoistic and

deliberately gets herself defeated in a memory game in which famous people are invoked. But

during the memory game Aparna observes Jaya and Sanjoy get closer; there is a double

implication here; the first is that as in the other two films Aparna’s moral viewpoint coincides

with Ray’s own as far as the men are concerned. Secondly, (if this is conceded) is Ray’s sense of

human weakness not only pointing to the men but also to Jaya’s awakened sexuality: “The

compromising of Ashim’s intellect and the moral despair of Jaya are both indications of the

emptiness of the generation represented by the four boys from Calcutta” v (Hood, 2007: 177).

Aparna has suffered two very major setbacks in life which she has felt very deeply about and

which have always stayed with her - her mother’s early death by burning, when she was only

twelve years old and her brother’s suicide under mysterious circumstances in a foreign land -

“Dada and I were very close,” she tells Ashim and turns her face away. This suffering is her past

contrasts with Ashim; when she finishes her account, she looks at him boldly and asks pointedly,

“You haven‘t suffered much in life, have you?” It is this absence of ‘pain’ in his life that may be

responsible for the casual way in which he approaches others, is the suggestion. There are

several instances of his arrogance and lack of concern exhibited by his group and Aparna takes

Ashim to see the caretaker’s sick wife, something they have not cared about although they have

known about it.

To the forest these friends come to escape the drudgeries of a civilized life but they come all

burdened in some way or the other. For one, they are burdened by their city arrogance and sense

of superiority. Hari the sportsman is particularly petty in his attitude and has been rejected by his

sophisticated girlfriend Atasi because of his one line reply to her five page letter. He seduces the

attractive tribal girl Duli (after both of them are inebriated) and indulges in a casual sexual

relation with her - and even pays her at the end because he thinks that concludes his

responsibility. Ray takes care to make Dhuli laugh here and indicate her disdain to this proffering

of money.

Although Aparna is attractive she seems deliberately almost asexual and one could see her as a

contrast to Jaya. She appears distant and aloof and although she knows that Ashim is attracted

but when he is chastened and indicates his eagerness to measure up she is not averse to him.

Although her position is similar to that of those in the other two films she is not without a

romantic side. Being intellectual and strong, she is not every man’s dream companion and has

had to face loneliness. But Ray does not doom her to it; he ends Aranyer Din Ratri with the

possibility of her finding a chastened Ashim as her companion – acceptance that Arindam and

Shyamalendu are denied.

Aditi, Tutul and Aparna and their precedents

In all three films the women played by Sharmila act as moral agents, rather than as flesh and

blood characters with desires and failings of their own. Although the male protagonists are

attracted to the respective women and pairing off does take place in one’s mind the films hardly

function as romances. It is almost as if Ray primarily wanted to make a statement with the

woman character as pretext, about the underlying vulnerability of successful men who have been

unable to handle success. The woman steps in here as someone who, without admitting change to

herself, chastens the man and offers him some hope of a righteous, moral and/or caring

existence. If there is another characteristic that the films have in common apart from the

portrayal of the ideal woman, it is the trope of alcohol - and hormonal responses to the other sex

- to connote moral weakness.

A repeating portrayal in a great artist’s work arouses one’s curiosity about precedents: are there

models that the film-maker has been influenced by? Given that Ray was a modernist in every

sense with an encyclopedic knowledge of cinema and literature, one is tempted to look westward

for them. But the woman exemplar under study seems surprisingly missing in western literature

and cinema, where protagonists are never exempt from such transformation. The key aspect of

someone like Elizabeth Bennett in Pride and Prejudice is that she and Darcy both change –

while the characters played by Sharmila remain unchanged – and Elizabeth has also no general

wisdom to offer Darcy, who is not ‘weak’. The same is true for virtually every other example;

weaknesses are to be found in both men and women, although they may be of different sorts, and

they must both change.

If one were to seek out closer models, the ones that surprisingly emerge in cinema are those from

reformist Indian cinema of the 1930s and 1940s where inherently strong women reform weak

men, films like Franz Osten’s Durga (1939), NR Acharya’s Azad (1940) and Jhoola (1941) vi.

The motif has been traced to the reformist movements under colonialism when the position of

women in society was a key issue vii. Among the first of the reformers to articulate issues

pertaining to women was Raja Ram Mohun Roy who also founded the Brahmo Samaj. The

cornerstone of Roy’s reformism was his opposition to the institution of sati but this led on to

other things:

“He not only linked sati to the community’s mode of worship, but challenged its basis by

suggesting new sex role norms and sexual stereotypes and by showing the spurious links the

practice had with Hindu traditions. The word sati is a derivative of the root sat, truth or

goodness. The widow by dying with her husband proved that she was true to him and virtuous.

Roy shifted the onus of showing fidelity and showing rectitude to others. While men seemed to

him, ‘naturally weak’ and ‘prone to be led astray by temptations of temporary gratifications’,

women seemed to him to have ‘firmness of mind, resolution, trustworthiness and virtue….’” viii.

One catches in the above passage some sense of where the strong woman could have come out of

but ‘reform’ in nineteenth century India could not itself have come about without models of

some kind in India’s past. If one looks at Indian mythology one also finds the ‘strong woman

who reforms her husband’ conspicuous in the characters of Tara (Vali’s wife) and Mandodari

(Ravana’s wife); both advised their men correctly but unsuccessfully. One cannot expect these

mythological ‘models’ to be directly mimicked by a modernist like Ray in the 1960s. But

keeping in mind what was said about Ram Mohun Roy, texts in which to look for women

characters with wisdom absent in the men, who also articulate their positions admirably, might

be 19th and early 20th Century literature from Bengal. The most important writers of fiction were

Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Saratchandra Chatterjee and Rabindranath Tagore and Ray might

have been influenced (consciously or unconsciously) by them. Since these writers would

naturally also display the concerns of the reform movements some sense of how they regarded

women in their works could be helpful.

To begin with the earliest candidate Bankim has several strong women in novels like

Kapalkundala (1866) and Anandmath (1882) but he is more preoccupied with the nationalist

question; his women, who act rather than articulate, do not quite bear comparison with those of

Satyajit Ray. The second possible writer would be Saratchandra Chatterjee best known for

Devdas (1917) which deals with a weak man (an alcoholic) and the two women who love him

but he also introduces the articulate woman through his fiction. In Sesh Prashna (1931)

Saratchandra Chatterjee looks into the issue of subjugation of women, and through this novel he

tries to understand the women’s question, particularly through the character of Kamal his heroine

he tries to make sense of the questions plaguing society regarding women-the nature of love,

marriage, the relationship a man can have with a woman, and also the degree of freedom and

emancipation. Kamal constantly makes everyone around her uncomfortable with her thoughts,

deeds, words whose sense of freedom too threatens patriarchy. As an instance she surprises

everyone by denouncing the Taj Mahal as a monument to an emperor’s ego, and not to

unflinching love. In the story Kamal who is born of a European planter father, and a widowed

Bengali mother is living out of wedlock with an unscrupulous businessman named Shibnath who

abandons her. Kamal’s unconventional background allows Saratchandra to put forward radical

views through her effectively since she is so different. But this also means that it is rather far

from the purpose here; moreover, novels by both Bankim and Saratchandra are intricate and

convoluted and despite their preoccupation with strong women who dare to break patriarchal

norms, making connections would be difficult. This leaves us with Tagore and his stories would

perhaps be where we should look for workable models.

Streer Patra (1914) is a short story in an epistolary for which narrates the life of Mrinal, the

mejobou (second daughter-in-law) of a well-to-do family, enduring a loveless conjugal life

within the marital home in Kolkata. Mrinal’s giving birth to a still born child and the entry of the

orphan destitute girl Bindu precipitates the crisis. This crisis also prompts Mrinal to do what she

thinks is right and endeavors to be her true self even when the male members of the family find it

challenging their authority. This exposes the true position of women within the Bengali family.

Bindu is made to feel that she is a dependent at every step and coerced into marriage with a

mentally challenged man so that the family doesn’t have to support her financially. After

repeated attempts to escape the traumatic situation the girl commits suicide. When the girl dies,

Mrinal decides to stay back in Puri and leave her husband, to whom she writes a letter addressing

all her grievances thus relinquishing her role as a ‘wife’. The title of the story is particularly

interesting as Tagore seems to include the whole of female sex in his redressal of the wrongs

meted out to women. Instead of calling it ‘Mrinal r chhitthi’ he calls it ‘Streer Patra’ where the

word ‘stree’ actually represents the feminine in the Bengali language. Mrinal is the articulate

woman with a clear idea of the woman’s position in a traditional patriarchal family who is

articulating her position as she leaves. The fact that she is leaving her husband puts it in a

different context from that in Ray’s three films but trope of the weak man/husband is in

attendance, justifying the comparison.

At its very core, Samapti (1893) is a love story, which shows the rather painful journey of its

lead character Mrinmoyi from being an unruly and carefree young girl to a loving wife. A young

graduate named Amulya has just finished his exams and returned to his riverside village in

Bengal with an assumed air of urban supremacy. While alighting from the boat on the muddy

banks of the river, he slips and falls, setting a free-spirited tomboyish girl named Mrinmoyi into

an uncontrollable bout of laughter. Not at all amused by this disastrous insult, Amulya is rather

furious with the girl, who soon scoots from the spot. Still, when his mother asks him to get

married before going back to the city to study further, Amulya insists on taking Mrinmoyi as his

bride, because by now, after another close encounter with the girl, he has fallen in love.

Mrinmoyi, however, is severely opposed to the very notion of marriage, because it would

inevitably bind her to a domestic life — putting an end to her happy-go-lucky ways. But as was

the practice during those days, she does not have a say in the matter, and is promptly married off

to Amulya. On the night of his wedding, Amulya realizes from her refusal to share the conjugal

bed that his wife has been forced into the marriage. When he assures her that he married her ‘for

what she is’ - the young girl asks him, “Don’t I have a choice too?” Not willing to win her by

force, Amulya returns to the city, leaving Mrinmoyi behind. And it is then, that Mrinmoyi begins

to realize that she is actually beginning to miss the man who she had refused to accept as her

husband. This story ends happily but it contains the sense that a girl who is still not fully an adult

can take decisions of her own and that only when the man respects her choices – which may be

contrary to patriarchal norms – can there be fulfillment.

In Aparachita (1916), a well to do aristocratic family decides to get their only son married to a

doctor’s beautiful daughter but only after they have received the dowry (an amount of gold

which has been promised). The bridegroom does nothing and goes long meekly. The doctor (Dr

Sen) finds it appalling to get his daughter married into a family he feels values gold more than

his daughter and calls off the wedding. The bridegroom’s family stomps off in a huff, feeling

slighted and stating that no one in their right minds would marry the girl. Years later in a chance

meeting in a train compartment the eligible bachelor rejected by Dr Sen who had been smitten by

Kalyani’s beauty meets her again. Afraid of losing her once again the man broaches the topic of

marriage only to be turned down by Kalyani this time, who asserts that her duty to her

motherland as a teacher far exceeds that of her need to get married, lose her identity to gain one,

as the wife or daughter-in-law of the family to that of an educated and emancipated woman. In

this story, again, there is the sense of a weak man having ‘missed’ the ideal wife because of his

being enmeshed in patriarchy.

In each of the stories above the woman is a victim of patriarchy but triumphs by standing up to

it. The man himself has taken advantage of the same patriarchy or has simply not taken a moral

stand against its conventions although that would have been right. Ray is not dealing with

patriarchy in the same way since he worked in a different era but another fact nonetheless needs

to be noted. Instead of making the women played by Sharmila Tagore the victims of patriarchy

Ray places them outside this field, as it were, as independent commentators ix. The instruction

they administer to weak men is, essentially, directed at the patriarchy the men are enmeshed in.

Looking at the three male protagonists, there is more than a suggestion that they are deeply

caught up in patriarchy through the institutions in which they have arisen - although this is more

explicit in Nayak, in which it seems natural for aspiring actresses to offer themselves to the male

stars in the film industry, or Seemabaddha in which an aged director Sir Barun Roy

(Harindranath Chattopadhyay), makes eyes at the women connected to the junior officials, as

though he was not required to maintain decorum.

All three Bengali writers were deeply engaged in reform in which the emancipation of women

was a significant constituent. As already implied Ram Mohun Roy was caught between

reforming Hinduism and affirming its ‘true’ values. This, it can be argued, meant selecting those

aspects of Hinduism (among a host of others) that a nationalist could actually look upon with

pride. The sacred texts he drew upon could have been the epics but, being tales, what they meant

would then also be ambiguous. The only sacred text (because it was in the nature of law)

unambiguous in its instruction might have been Manusmriti, although the objectionable aspects

of this sacred text with regard to women – from today’s democratic perspective – would far

outweigh its positive aspects. The British also took it seriously and incorporated some of it into

law for the Hindus while ignoring others x.

Women’s rights in the Manusmriti and their apparent impact

There are some sayings on women’s rights that are regarded positively (e.g. 51 to 63 in Chapter

3) from today’s perspective and here are some which could be relevant from the viewpoint

chosen here xi:

Chapter 3, No. 51: No father who knows (the law) must take even the smallest gratuity for his

daughter; for a man who, through avarice, takes a gratuity, is a seller of his offspring.”

Chapter 3, No. 52: “But those (male) relations who, in their folly, live on the separate property

of women, (e.g. appropriate) the beasts of burden, carriages, and clothes of women, commit sin

and will sink into hell.”

Chapter 3, No. 55: “Women must be honored and adorned by their fathers, brothers, husbands,

and brothers-in-law, who desire (their own) welfare.”

Chapter 5,No. 1: “Day and night it’s the duty of a husband to protect his wife and respect her

individuality.”

Chapter 11, No. 7: “A husband under no circumstances or intention should forcefully bind his

wife in matrimony nor should he protect her without her wishes…”

Chapter 13, No. 9: “A wife, whose freedom is compromised by the narrow mindedness or

shrewdness of her husband and family members, shall be rightful in leaving her relations behind

and begin the journey of finding herself.”

Apart from these rules involving women Manu also frowns upon alcohol drinking, which is

clubbed (Chapter IX, Verse 235) with the worst kinds of crime. It should be noted that the entire

Manusmriti reads as though it is instruction that assumes patriarchy as the natural order; if

women are granted an honorable place, it is still not an equal place alongside men admitting

separate needs of their own.

It is striking how close some of the positive utterances/ sayings about women are in spirit to

Tagore’s stories like ‘Samapti’ and ‘Stree Patra’ where they may even have been actualized.

Tagore in Chokher Bali argues in favor of woman’s moral superiority over men. Issues of

widowhood, widow remarriage etc. have been treated by Bankim in his essay ‘Samya’ and

Saratchandra Chatterjee in his novels. The changes in women’s consciousness as reflected in

literature could be seen and mostly related to the national movement when it was necessary to

rejuvenate Hinduism. Suryamukhi of Visavriksha (1873) leaves her home and Bhramar of

Krishnakanter Will questions the husband’s right to dominate his wife. Tagore in Ghare Baire examined such issues as the woman’s right to love, her defiance of the marital codes as imposed

by society and her right to get involved in public life. Tanika Sarkar xii posits that in

Kapalkundala, Bankim presents a distinct, asocial woman who remains thoroughly

undomesticated in spite of experiencing the most perfect form of domestic and sexual love. The

heroine then embodies the ideal of a non-attached person possessing wisdom, kindness, concern

and self-sacrifice but finds fulfillment only in self-reliance.

The spirit of enquiry into the nature of the universe expressed in innumerable such statements in

the Upanishads lend themselves to a synthesis with modern scientific thinking as expressed in

numerous of Tagore’s songs and poems and cultivated in Shantiniketan which Ray in his stay

there could not have bypassed. On woman Tagore states in an essay, “Woman, let me repeat, has

two aspects – in one she is the Mother; in the other the Beloved. I have already spoken of the

spiritual endeavor that characterizes the first, viz., the striving not merely for giving birth to her

child, but for creating the best possible child – not as an addition to the number of men, but as

one of the heroic souls who may win victory in man’s eternal fight against evil in his social life

and natural surroundings. As the Beloved, it is woman’s part to infuse life into all the aspirations

of man; and the spiritual power that enables her to do so I call charm, and was known in India as

Shakti.” xiii Therefore, it comes as no surprise that like many others before him Ray turned to the

same sources while drawing up an ideal woman played by Sharmila in the three films even to the

extent of making the men the achievers and the women essentially ‘honored and adorned’.

Instead of delineating his women characters as individuals with desires and living for themselves

he made them guides for men, thus ‘honoring’ them instead of allowing them autonomy. They

portray an ideal in a limitless but ultimately harmonious natural drama that all the other

characters are a part of. After all, Ray’s spiritual heritage which imbued his films was derived

from his Brahmo-Vedantic background.

Notes/References:

Notes/References:

| I. |

Dasgupta, Chidananda, The Cinema of Satyajit Ray, New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1980, p 97.

|

| II. |

Cooper, Darius, Between Tradition and Modernity: The Cinema of Satyajit Ray, New York: Cambridge

University Press, p 79

|

| III. |

Ibid, p 133

|

| IV. |

Dasgupta, Chidananda,The Cinema of satyajit Ray, New Delhi: National Book trust, pp 95.

|

| V. |

Hood, John, Beyond the World of Apu: The Cinema of Satyajit Ray, New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2007,

pp 177.

|

| VI. |

Raghavendra, MK, Seduced by the Familiar: Narration and Meaning in Indian Popular Cinema, New

Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp 88-90.

|

| VII. |

Ibid, pp 91-2.

|

| VIII. |

Nandy, Ashis, At the Edge of Psychology: Essays in Politics and Culture, New Delhi: Oxford University

Press, 1980, p 12.

|

| IX. |

It may be significant that the women are not achievers in their own right although Aditi in Nayak runs

a small magazine for which she is personally collecting subscriptions. Achievement, whatever its

problematics, is entirely a male bastion

|

| X. |

Flavia, Agnes, Law and Gender Inequality: The Politics of Women's Rights in India, New Delhi: Oxford

University Press, 2001, pp 41-45

|

| XI. |

|

| XII. |

Sarkar, Tanika, Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion and Cultural Nationalism, New Delhi:

Permanent Black, 2003, p 146.

|

| XIII. |

Tagore, Rabindranath, ‘Woman’ from Selected Essays, New Delhi: Rupa, 2004, p 209.

|

Devapriya Sanyal has a PhD from Centre for English Studies, JNU and is the author of

Through the Eyes of a Cinematographer: The Biography of Soumendu Roy (HarperCollins,

2017). She likes teaching and writing, though not necessarily in that order. She loves

reading, watching films and travelling.

Courtesy: bharat ratna satyajit ray

Courtesy: A still from 'Nayak'

Courtesy: Satyajit Ray: Aranyer Din Ratri

Courtesy: “Seemabaddha” (Ray, 1971)

|

|