|

Background

Zhang Yimou is the best known film director from what is known as the ‘Fifth Generation’ of filmmakers coming out of mainland China. The cinema of mainland China is one of three distinct  streams in Chinese-language cinema – together with the cinema of Hong Kong and the cinema of Taiwan. Motion pictures were introduced into China as early as 1886 and the revolution of 1949 saw motion pictures becoming an important tool of propaganda which ceased after Mao. Zhang’s films, coming after the Cultural Revolution, are hardly propaganda but reading their politics can still be rewarding. Interpreting them is rewarding because Zhang has worked in a multitude of ‘apolitical’ genres including the historical/ mythological epic and some of his films have been worldwide hits. Since many of them are intended as mass entertainment, they yield their political meaning despite themselves, unlike propaganda in which political discourse is deliberate. streams in Chinese-language cinema – together with the cinema of Hong Kong and the cinema of Taiwan. Motion pictures were introduced into China as early as 1886 and the revolution of 1949 saw motion pictures becoming an important tool of propaganda which ceased after Mao. Zhang’s films, coming after the Cultural Revolution, are hardly propaganda but reading their politics can still be rewarding. Interpreting them is rewarding because Zhang has worked in a multitude of ‘apolitical’ genres including the historical/ mythological epic and some of his films have been worldwide hits. Since many of them are intended as mass entertainment, they yield their political meaning despite themselves, unlike propaganda in which political discourse is deliberate.

Zhang’s films are part of a national cinema and they belong to a category about which there is perhaps still some uncertainty. Among the eight categories identified under ‘national cinema’ (1), they could fall readily under ‘totalitarian cinema’, ‘art cinema’ as well as ‘Asian commercial successes’. Although films from countries like Iran and China today may not be as strictly ‘totalitarian’ as those of the former Soviet Bloc and Mao’s China were understood to be and they are widely accepted as art cinema or entertainment, the degree of censorship in the respective countries must still be taken into account while categorizing them. Zhang Yimou works in a space in which there is strict censorship but he is also an auteur, and the works of an auteur – with a large following – from a political system which is uncommunicative about its own workings are doubly interesting. But before going on to examine Zhang’s films it is necessary to get a broad sense of how cinema developed in China after 1949.

Chinese cinema and politics in the 1950s and 1960s

The CCP control of Chinese cinema proceeded quickly in the areas of administration, distribution and exhibition, production and criticism. In April 1949 Northeast Studio released the first socialist feature, Bridge (Qiao, dir. Wang Bin). Set during the liberation war, the film tells how against the odds workers complete the construction of a bridge in time for PLA soldiers to move across the Sungari River (2). At the same time as glorifying the collective wisdomof the proletariat, the film also shows the transformation of the chief engineer, whose initial lack of confidence in the strengths of the working classes is in the end proved wrong. In its tripartite attention to the revolutionary war, the wisdom of the proletariat and the transformation of the intellectuals, the film points to three recurring themes in socialist cinema. As may be gathered, the earliest films after the CCP consolidated itself were war films. War films functioned also as historical films due to the fact that the CCP, now securely in power, had resorted to cinema to provide a suitable  teleology for the history of modern China – as a process in which the Communists led the Chinese people. But at the same time, class struggle also needed to be depicted to assist the land reform movement and to remind its audience of the ‘permanent’ threat of class enemies. The White-Haired Girl (Baimao nü, dir. Wang Bin, Shui Hua, 1950) is a popular adaptation of a 1944 CCP-sanctioned village opera from the Yan’an era (3). The film presents the villagers as less superstitious and more responsive to Communist mobilization than the opera version and there are other factors such as the suggestion of female sexuality which makes the film transcend its political function, but this artistic freedom was quickly belied a little later – the release of The Life of Wu Xun (Wu Xun zhuan, dir. Sun Yu, 1950). teleology for the history of modern China – as a process in which the Communists led the Chinese people. But at the same time, class struggle also needed to be depicted to assist the land reform movement and to remind its audience of the ‘permanent’ threat of class enemies. The White-Haired Girl (Baimao nü, dir. Wang Bin, Shui Hua, 1950) is a popular adaptation of a 1944 CCP-sanctioned village opera from the Yan’an era (3). The film presents the villagers as less superstitious and more responsive to Communist mobilization than the opera version and there are other factors such as the suggestion of female sexuality which makes the film transcend its political function, but this artistic freedom was quickly belied a little later – the release of The Life of Wu Xun (Wu Xun zhuan, dir. Sun Yu, 1950).

Wu Xu was a poverty-stricken beggar in the years of the Qing dynasty who later dedicated his life to raising money and offering free education to poor children. The film’s theme was perhaps ‘insufficiently progressive’ because Chiang Kai-shek had reportedly praised Wu Xun during the war. But the project was still revived (by the privately owned studio Kunlun) due to a paucity of screenplays and several changes were made, including a peasant uprising and a critical assessment of Wu Xun from a post-liberation perspective. The film drew enthusiastic crowds and garnered rave reviews and, perhaps emboldened, the director brought a print to Beijing, where he cut a one-part version of less than three hours and screened it to a special audience including Premier Zhou Enlai, Yuan Muzhi and about a hundred other CCP leaders. Mao was not present at the screening but watched the film soon afterwards and detected serious problems which he gave voice to. He wrote an editorial and had People’s Daily publish it on 20 May 1951. The editorial criticized the film for ‘promoting feudal culture’, ‘distorting peasants’ revolutionary struggles and misrepresenting Chinese history’. Among the issues raised was that only the Party – and not filmmakers – had the right to represent history and that peasants should take on screen the image of fighters and not reformists. Since Mao’s editorial diagnosed the initial media praise of the film as the infiltration of bourgeois thought into the CCP, a nationwide campaign was launched and it spread to all levels of the state. From November 1951 to January 1952, entire film circles were forced to go through ‘rectification’. Not only did Sun Yu admit his errors in newspapers, but Premier Zhou himself apparently also apologized for his oversight to the CCP central committee (4). Since, subsequently, eager responses were received from everywhere to substantiate Chairman Mao’s criticism of the film (5), Mao had, in effect, marshaled his support within the party through a film review.

The Wu Xun incident has been subsequently studied by film historians and its importance is attached to Mao’s personal hand in a campaign against a film – which he described as ‘poisonous’. Why Mao chose to do this is uncertain but it has been argued that since Chinese cinema was dominated by the Shanghai – seen as dominated by capitalism, bourgeois and petit-bourgeois ideas – this was a way of taking it along the path to Yan’an, i.e. the acknowledgment by the Shanghai-affiliated, urban-centered artists of the ideological authorityof the Yan’an-trained, rural-educated cadres. But apart from this, it also prefigured a strategy frequently employed by Mao – especially during the Cultural Revolution – to intervene in culture as a way of strengthening his hold over the Party (6), i.e.: forcing cultural figures and party leaders to submit to his authority by admitting their ideological errors openly.

Political prescriptions for what cinema should be was confusing in the 1950s with official pronouncements emphasizing seemingly contrary notions like ‘revolutionary idealism’, revolutionary realism’ and ‘revolutionary romanticism’ (7) but the general push was towards the portrayal of workers and peasants, the elimination of all ambivalence and the ascendancy of political correctness as the highest operating principle. Correspondingly, public spaces with political connotations – factories, mines, villages and military camps – become the preferred settings. The favored plot usually ends with the triumph of the public over the private, leaving little or no room for addressing personal dilemmas and crises.

While ‘socialist realism’ was accepted as the credo, the CCP position under Mao was never as clearly articulated as the Soviet position under Stalin had been in the 1930s. The purpose was ostensibly the interpellation of the audience as voluntary historical subjects of the socialist nation-state (8); but Mao’s personal interventions – which sometimes seemed capricious – tend to cloud this hypothesis. Mao perhaps extended or held back approval or attacked at will primarily to further the cult of personality around himself – since most of his interventions led to members of the CCP admitting their errors. Even if Mao was not acting deliberately in this way, there is little evidence (as we shall see) in later Chinese cinema that a Marxist worldview was inculcated under Mao. When he launched the ‘Hundred Flowers’ campaign, it was immediately compared by Western Marxist scholars to the ‘Thaw’ in the USSR under Khruschev but it soon became evident that it was a ploy by Mao to bring dissent into the open. Scholars of Soviet cinema point out the utopian mindset of many of the intellectuals of the Thaw period (9) which apparently finds no correlation in China. Perhaps the most plausible hypothesis about China is that Mao’s socialist utopianism was not intellectual but intended to appeal elsewhere. Itcommanded a broad-based following in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly among the young generation because of its negation of humanism and its appeal to it to surrender private life and participate wholly in public activity. The generation mobilized by Mao was made eager to sublimate everyday life into an artistic experience teeming with theatricality and ecstasy (10). It was perhaps less a mobilization based on political understanding than a cult of worship.

Cinema had been stagnating in the 1950s and the Hundred Flowers campaign helped (11). The effects of the liberal reform measures resulting from the Hundred Flowers campaign were immediate: annual feature production almost doubled, rising from twenty-three in 1955 to forty-two in 1956 and doubled again in 1957. The crowning achievements were perhaps three satirical comedies made by Lu Ban ridiculing the bureaucracy: Before the New Director Arrives (Xin juzhang daolai zhiqian, 1956), A Man with Bad Manners (Buju xiaoje de ren, 1956) and The Unfinished Comedies (Wei wancheng de xijü, 1957). The Hundred Flowers campaign came to an end with the launching of the Anti-Rightist movement. The Ministry of Culture judged The Unfinished Comedies to be a ‘poisonous weed’ rather than a blossoming flower, and numerous other films were identified as ‘white flags’ (or non-revolutionary) – to be brought down. Critics, intellectuals and filmmakers were classified as ‘Rightists’ and banished from the public eye, some for over two decades. As before, many others (including party leaders) had to admit their errors to survive politically. The Anti-Rightist movement in 1957 swiftly led to the Great Leap Forward in 1958. During this time Chinese cinema still had various genres which went back to before the Revolution like the opera film, the ethnic minority film and the war film some of which were nationalist in design and continued under CCP rule. Socialist realism, therefore, was not the only aesthetic although it was favored. But this was only until 1965 because the Cultural Revolution was launched in 1966 and during the next decade only 79 feature films were distributed including six remakes and thirty-six foreign titles (12). We can therefore treat the period up to the later seventies as gap in Chinese film history since our interest is primarily in how cinema reemerged after Mao.

Chinese cinema up to the Cultural Revolution has been usefully divided into two political categories, those owing their allegiance to Yan’an and Shanghai respectively. The former is identified largely though its worker-peasant-soldier themes (13) while the latter embraces more variety thematically and includes characters who are more ambiguously conceived (‘middle’ characters) although their class antecedents still plays a determining part in their construction. Since both categories favored political didacticism it will be interesting to identify the differences between Maoist cinema and Stalinist cinema. Stalinist cinema was principally concerned with the production of history, events from the past featuring as ‘prototypes’ (14) and biographies of historical models becoming a favored genre. In Chinese cinema the favored model is the melodrama in which there is a process of education, which has been traced to the Confucian stress on self-improvement and broader social education (15); Mao described people as blank sheets of paper to be written upon.

Reversals

The political history of China in the decade after Mao’s death in 1976 is dominated by a series of ideological reversals. If this had been true of the Stalin era in the USSR in which yesterday’s revolutionaries became today’s agents of Western imperialism, it was much more so in China. Studying Soviet cinema after 1917, one finds that there are genuine political issues being debated upon until well into the Stalin era even when the cinema is openly propagandist. The issue of the collectivization of agriculture, for instance, is dealt with in films like Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930), Eisenstein’s The General Line (1929) and Bezhin Meadow (1937) although the last film was not allowed to be completed. The emancipation of women was dealt with in Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa (1927) and in Fridrikh Ermler’s Fragments of an Empire (1929). Ideological positions are always coming into conflict as in Mikhail Romm’s Mechta (1943). If there was more theoretical consistency – although the status of individuals could change overnight – this was because the leaders of the Russian Revolution had argued out their political positions extensively in tracts; each leader – Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky and Bukharin – had a political position which was widely understood. Political struggles therefore began as ideological disagreements and an instance is the struggle in the mid 1920s between Stalin and Bukarin on one side and Zinoviev and Kamenev on the other against the pro-muzhik policy expounded by the former group (16). The survival of Communism in the USSR after Stalin – despite the horrors perpetrated under him – perhaps owed to political theory remaining intact.

‘Maoist theory’ is much more nebulous since Mao expressed himself chiefly in maxims and practical instructions on matters ranging from physical education to guerilla war and informed by local conditions. They are mainly primers containing assertions in which categories are simply drawn and these categories are identified for the limited purpose of determining the capacity of each one for ‘revolutionary action’. They cannot be described as analyses attempting to reflect on matters like history, philosophy and culture. An instance is Mao’s 1951 review of the film The Life of Wu Xun (17) – dealt with earlier – which became the occasion for many leaders to admit their political errors. On scrutinizing the review in question we find that what Mao does essentially is to denounce people for propagating feudal culture and eulogizing a class which ‘slavishly flattered the feudal rulers’. Mao lists the writers who wrote about the film positively – including its director Sun Yu – and, rather than being a provocation intended to spark off a cultural debate, it conveys the sense of a dire warning – that the cultural views and activities of some people have been noted. Instead of encouraging dialogue on politics and history, therefore, political discourse in the public space was apparently left deliberately unresolved so that Mao – and those chosen by him – could remain arbiters on what was politically correct.

This situation in which political mores were clouded in doubt apparently left the public space a bed of ideological confusion after Mao’s death and it was out of this confusion that Deng Xiaoping emerged. Because of the arbitrariness of many political dispensations under Mao, Chinese cinema had been unwilling to take chances and had become extremely predictable by the 1970s. The affirmation underlying every film was the myth of progress under Communism: prior to 1949, life was bad, except in those liberated areas where the Communist Party already held sway. After the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, everything was good and progressing steadily towards a Communist utopia (18). All films which concluded before the Revolution or in areas outside those liberated by the Communists before 1949 concluded unhappily for the protagonists while those after the Revolution or in the liberated areas had happy endings. This followed from Mao’s theory of culture propagated before the Revolution in his Yan’an talks. Mao had expressly stated that although works of exposure were appropriate to any critique of the old society, they were not appropriate to works representing the liberated areas controlled by the Party, being neither ‘realistic’ nor serving the Party’s political goals (19). The result of the policy was that all problems were treated as either owing to the pre-revolutionary past or to foreign agencies. The difference between the Shanghai and the Yan’an approaches was that while the former could conceive of positive characters with ideological problems, the latter demonized all people with wrong ideologies (20).

Since political thought had hardly developed in Mao’s China, his death in 1976 did not lead to a repudiation of his politics and for several years after the event, the leadership continued to nominally adhere to his ‘theories’ although in actual practice political and economic decisions did not honor his principles. In the two years before Mao’s death, most historians see a three-way struggle in the Party – between the revolutionary Maoists (who were later identified with the Gang of Four), the restorationists (who gathered around Hua Guofeng) , and the reformists headed by Deng Xiaoping. The revolutionary Maoists favored continuation of Cultural Revolution policies, the restorationists who advocated a return to pre-Cultural Revolution policies. The reformists, as opposed to these two, advocated the introduction of pro-market reforms to improve material conditions. Deng, who had been brought back as Vice-Premier by Zhou Enlai after having been removed from power in 1966 at the commencement of the Cultural Revolution, had been removed once again shortly after Zhou’s death in January 1976 – with Hua Guofeng becoming Premier. Deng did not return to positions of power immediately after Mao’s death and was brought back only later by Hua to fight extremists within the Party.

It should be noted here that the Gang of Four were arrested within a month of Mao’s death in September 1976 strictly on the basis of Maoist principles and they were labeled ‘ultra-rightists’ and ‘counter-revolutionaries who were determined to restore capitalism’ by Hua, whose principle political pronouncement was that whatever decisions Mao had taken should be upheld and whatever directions he had given must be respected (the two ‘whatevers’). By 1977 support for Deng grew within the Party chiefly from those who (like him) had suffered because of the Cultural Revolution. Deng quoted Mao – ‘seek truth from facts’ – to which he added his own slogan ‘practice is the sole criterion for truth’ (21). The implication here is that rather than being a reconsideration of political theory, Deng began by repudiating theory and dwelling only on practice – confirming that Maoist theory was hollow by the 1970s and depended enormously on the iconic presence of the Chairman rather than any political doctrine that he ostensibly stood for (22). A matter of pertinence here is that Marxist historians had once wondered at what Maoism represented politically – since there was virtually no Socialist-Marxist influence in China prior to 1917. Even at the foundation Congress of the CCP in 1921, the number of delegates numbered twelve and the total membership was only fifty-seven (of which Mao was one) (23). If China had been seething with anti-imperialism and agrarian revolt much earlier, the movements and secret societies involved in the risings and revolts were all traditional in character and based on ancient religious cults. But Maoism had acquired the characteristics of a cult by the time of the Cultural Revolution and political rhetoric had acquired the characteristics of incantation.

Chinese Cinema after Mao

Chinese cinema took a while to stabilize after Deng’s ascent but, by the 1980s, we begin to get a sense of where Mao had left culture politically through his interventions in the life of the nation. It must be brought to the reader’s attention that Chinese cinema before the Revolution had been influenced deeply by leftist ideas. The first big success in Chinese cinema was Zhang Shichuan’s Orphan Rescues Grandfather (1923) produced by Minxing Film Company. This film, like many others which followed, took its social responsibilities seriously and engaged in moral didacticism. The struggle in most of these socially conscious films was between the good as represented by motherly love, philanthropy and education and evil by hoary social customs, the tyranny of the traditional family and warlords. Both Mixing and a newer studio Lianhua Film Company (founded 1930) were progressive in outlook. The latter company, mindful of its social responsibilities, staffed itself with educated people with Western outlooks (24). In fact the social consciousness of Chinese cinema was credited with driving pure entertainment genres like martial arts films and ghost films out of the market. Although the KMT government was cracking down on communists, leftist titles were considered compatible with KMT policies and the censors picked leftist films to represent China at international film festivals; this has been attributed to the plurality of political interests within the KMT. Class struggle was a common theme in the films of the 1930s in which the villains are capitalists and landlords while the heroes are from the working class (25). Although other genres like the ‘soft film’ which provided tasteful entertainment and the patriotic war film flourished thereafter, the leftist film did not lose ground even after the War was over and Japan defeated. Their political discourses are, in fact, more reasoned out than in cinema under Mao.

The earliest films to reexamine the Mao era came at the end of the 1970s and naturally looked at the scars left by the Cultural Revolution; they have been referred to by critics as ‘scar’ films (26). Two of the most important of the films were Bitter Laughter (dir. Yang Yanjin, Deng Yimin, 1979) and The Legend of Tianyun Mountain (dir. Xie Jin, 1980), the latter film tracing the commencement of political repression to the Anti-Rightist Campaign of the late 1950s. Xie Jin had earlier made Stage Sisters (1964) which one of the first casualties of the Cultural Revolution. This film has perhaps the same position with regard to the Cultural Revolution that The Life of Wu Xun had with regard to the Anti-Rightist Campaign. Stage Sisters had been encouraged by Xia Yan, Vice-Minister for Culture with whom Jian Qing (Madame Mao) had a running feud. This may have been a cause for the film being denounced as being a ‘typical, decadent pro-bourgeois drama’ and banned (27).

The Legend of Tianyun Mountain is about people in key positions using their power for personal ends – in the guise of following Party policy. Song Wei is in love with her team leader Luo Qun but the latter is accused of being a rightist and condemned to hard labor through the machinations of Wu Yao, who marries Song. Luo Quon marries Song’s best friend Feng Qinglan instead and the two live a hard life for two decades while Song and her husband are cozy as senior party officials in the same province. An important aspect of the film is that Song and Luo Qun are shown to be living meaningful lives amidst the rural populace and it does not merely lament their lot. Rather than take issue with the justice of the Anti-Rightist Campaign, therefore, the film deals with how it was misused locally; i.e. the decisions of the Party are consistently treated as beyond questioning. Song dies eventually but we are made to draw satisfaction from Feng and Wu Lao getting divorced – because of Feng’s efforts to rehabilitate Luo Qun being resisted by her husband.

If the impenetrability of the Party’s political decisions is a characteristic informing virtually every film of the two decades after Mao, it manifests itself in two basic ways. The Blue Kite (dir: Zhuangzhuang Tian, 1993) made thirteen years after The Legend of Tianyun Mountain – and banned – has virtually the same political discourse as Xie Jin’s film – that the decisions of the Party were used locally to serve private ends. The film covers many more campaigns than Tianyun Mountain and ends with the Cultural Revolution but while it is more explicit in its brutality, it does not shed more light on Party policy and political decisions. Its implication is that political decisions – coming from ‘above’ – can neither be questioned nor even understood. In the other kind of film, which is set in pre-Communist China – Stage Sisters and Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth (1985) – Communism only just arrives or is approaching and it becomes an emblem of hope. But there is still nebulousness in what Communism represents to the people at large.

Before I go on to examine Zhang Yimou’s films, which are what this essay is actually about, the ‘impenetrability’ of Party dictate suggests that policy was imposed. This should make the Chinese films comparable to those from the Soviet Bloc before 1989, when Communism was still intact but the history of policy was being covertly criticized. But when we make the comparison, we find significant differences between the Chinese films and those from Poland or Hungary. Andrez Wajda’s Man of Marble (1975) and Pál Gábor’s Angi Vera (1979) are both examinations of the Stalinist period. Wajda’s film looks at the Stakhanovite movement while the latter examines the Communist notion of self-criticism and how it was employed. There is a rational discourse around Marxist political principles and how politics played out in practice. In Tianyun Mountain we do not know why someone should be chosen for ‘rightist’ rather than another while The Blue Kite simply shows a Party official in abject fear when the Cultural Revolution breaks out. Party decisions and the identification of victims during each political campaign, it would seem, are as mysterious as Imperial missives are in Kafka’s story The Great Wall of China.

Categorizing Zhang Yimou’s films

Zhang Yimou, as already indicated, belongs to the Fifth Generation of filmmakers from Mainland China. The term applies to the film directors who began making films in the mid-1980s. Most of them are members of the first graduating class of Beijing Film Academy in the post-Cultural Revolution period. As a group, the Fifth Generation filmmakers were all born in the 1950s and grew up in the political turmoil of the 1960s. As may be expected none of them had an uninterrupted pre-college education. Their successes also follow a similar pattern: all having their directorial débuts in minor studios in interior China and establishing their names through international media (28). Unlike the Fourth Generation which grew up in an ideological charged atmosphere and is therefore Marxist-humanist in its leanings, members of the Fifth Generation (to which Chen Kaige also belongs) are regarded as rebels. They eschewed the melodramatic and overly theatrical elements of the earlier cinema (29) and tried to make their films more cinematic. A charge made against them is that they have ignored local audiences and present a dark view of China – both of tradition and political life – specifically for film festivals in the West. But since they experienced Maoism at its most virulent in their formative years it is reasonable to expect it to be registered in some subliminal or covert form although they are considered ‘Western’ and have been increasingly removed from mainstream filmmaking within China.

Zhang Yimou is an enormously versatile filmmaker who began as a director with Red Sorghum (1987), an exuberant film set in rural China during the War which won the Golden Bear in Berlin. This film has since been assessed as part of a trilogy about feminine sexuality which also protests the patriarchal system in pre-Communist China – the films are all about young women forced into marriage or servitude as concubines with much older men. The other films of the trilogy are Ju Dou (1990) and Raise the Red Lantern (1991). Zhang has also made films of contemporary life which critique the state of affairs in China and the administration – films like The Story of Qiu ju (1992) and Not One Less (1999). He has directed historical/mythological epic with martial arts as a key component. Hero (2002) was an international sensation but he has also made House of the Flying Daggers (2004) and Curse of the Golden Flower (2006). Apart from these, he has recreated Maoist times, the best known film being To Live (1994), which is partly set in the Cultural Revolution. It will be appropriate for my study of Zhang Yimou to begin with the earliest films, those like Red Sorghum – films about feminine sexuality in patriarchal society.

Sexuality and patriarchy

All three films in Zhang’s first trilogy begin with an older man acquiring a young wife or mistress. Red Sorghum (1987) begins with a voiceover of the protagonist’s grandson who reminisces over  his grandmother Jiu’er, a poor girl forced into marriage with Big Head Li, the leprous owner of a distillery. On her way to her husband’s house, she catches the attention of one of the men – a sedan carrier who later becomes the narrator’s grandfather. This man is instrumental in chasing away the bandit who accosts them. Shortly after the marriage the girl is returning to her parents as custom requires when she abducted by the same man (who is initially masked) and has sex with him. Shortly thereafter, Big Head Li is found murdered and the murderer is never found although it is later hinted that it was the sedan carrier. his grandmother Jiu’er, a poor girl forced into marriage with Big Head Li, the leprous owner of a distillery. On her way to her husband’s house, she catches the attention of one of the men – a sedan carrier who later becomes the narrator’s grandfather. This man is instrumental in chasing away the bandit who accosts them. Shortly after the marriage the girl is returning to her parents as custom requires when she abducted by the same man (who is initially masked) and has sex with him. Shortly thereafter, Big Head Li is found murdered and the murderer is never found although it is later hinted that it was the sedan carrier.

The distillery is now to be closed down but Jui’er is a spirited woman and decides run it – as a collective with Li’s deputy Luohan as her principal assistant. The sedan carrier now returns there drunk, makes his claim upon Jui’er and after a stormy interlude, becomes her husband. Luohan, naturally, finds this unbearable and leaves. The distillery prospers and Jiu’er’s husband is able to show his mettle with a feared local bandit. The invading Japanese forces arrive and they are constructing a road, an activity in which the locals are forced to participate. The invaders are brutal; the first casualty is the bandit and the next is Luohan, who is a captured Communist. The villagers now decide to attack the Japanese with explosives and wait for them at dawn but Jui’er is herself killed when she is conveying food to the waiting others.

Although the story of Red Sorghum is nominally about a strong woman, it is a man’s story of her life in which the woman yields to him at every turn. Apart from being abducted and seduced by him, the sedan carrier makes his claims upon her casually and her resistance is ineffectual. Luohan, who plays the gentleman, is shown to be at a disadvantage vis-à-vis this brutally masculine suitor. Jui’er’s choice of the man who becomes her husband has been interpreted as a choice which ‘liberates her from patriarchy’ (30) but one finds oneself wondering at the interpretation. The man forces himself upon her and it is the man who survives after Jiu’er dies a pointless death. The story which survives the events is carried forward by men from mouth to mouth – grandfather to son to grandson. The gentle Luohan joining the Communist cadres is perhaps also significant. After Li’s death, the distillery becomes a collective endeavor with Luohan being the selfless guiding spirit. Although this aspect is not problematized, with Jui’er’s second marriage and the birth of her child, the distillery seems less a collective enterprise run on classless lines than a family run business of a feudal/ patriarchal society. The question put here whether there is not a signification that patriarchy is more durable than the egalitarian principles embodied by ‘gender-neutral’ Communism (31).

In the second film of the trilogy Ju Dou (1990), Yang Tianquing works for his adoptive uncle Yang Jinshan who is a dyer of silk. The cruel Yang has been taking wives with the intention of begetting a son but, being impotent, has been blaming the women for it, even killing them. When Tianquing sees the new wife Ju Dou, he is immediately enamored of her and she responds passionately. The result is a son Tianbai who carries Jinshan’s name and not Tianquing’s. Jinshan is paralyzed one day and he attempts to kill the child when he finds out about the affair. The two lovers discover his intent and confine him to a barrel – until his accidental death. The surprising aspect of Ju Dou, however, is that the child Tianbai grows up sullen and unmanageable, with loyalty to Jinshan rather than his real father. He is eventually also responsible for his real father’s death because he cannot bear Tianquing and Ju Dou being in an illicit relationship.

There is no doubt that Zhang is sympathetic to the lovers and Jinshan is shown as despicable. This being the case, the ‘poetic justice’ that inflicted upon the lovers is curious. Ju Dou bears some resemblance to ‘noir’ and noir is usually about moral retribution. Those who transgress the moral code are punished and there is never any ambiguity about the acceptability of the code itself. Murder and betrayal of trust deserve punishment, noir asserts. Ju Dou is unusual in as much as the transgressed moral code is elusive. Looking at the lovers from a humanist perspective of today, they do not transgress and it is only the strictly patriarchal code invoked by the story that finds them guilty. Once this is conceded, where Zhang stands morally in relation to the story material is perplexing.

When the film begins the husband is made to appear hateful and the relationship between the lovers appears like justifiable relief within a hateful system. This is subsequently strengthened when the paralyzed husband tries to kill the child. But the turning point is when the child begins to look upon the old man as his father and the old man returns his love and treats him as his own son. Ju Dou tries to tell Tianbai that his real father is Tianqing but the boy hates Tianqing stubbornly. With Jinshan’s death, his property passes to the boy, who also then becomes the ‘moral’ agency punishing his mother and his biological father. Tianbai is squat and monstrous but since we still do not have a grasp of where Zhang Yimou stands in relation to his material, it may be useful to compare Ju Dou with another well-known film about sexual transgression in a rigidly patriarchal society – Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Crucified Lovers (1954). In that film a loyal employee of a rich printer is accidentally brought into a relationship with his employer’s wife. The two are taken to be adulterous although they are innocent. When they finally decide to kill themselves, the man confesses his love for the woman. She is shocked but indicates her reciprocation of his feelings and their relationship is therefore transformed. Where the man was only husband’s employee, he is now Lord and Master and their loyalties take on another hue.

When we compare the two films we find Zhang Yimou’s view to be much more ambivalent about the society it is set in. The most important aspect of the Chinese film is that where The Crucified Lovers denotes the emotion dominating the relationship as ‘love’ – because of the two being willing to die for the other – Ju Dou is consistent in dwelling on the relationship between Ju Dou and Tianqing as a carnal obsession. The fact that Tianqing is also much older than Ju Dou – although younger than his uncle – also gives this emphasis. The emotion that Tianbai feels towards his parents is one of disgust partly brought on by the ugly rumors in the town about their observed physical conduct. I therefore propose that while Mizoguchi is describing a rigidly patriarchal society and its victims with evident sympathy towards the victims, Zhang is divided between his humanist side – suggested by his sympathy for the victims – and his support of patriarchy.

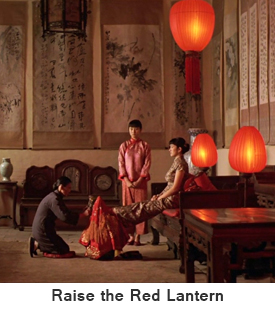

The third film Raise the Red Lantern (1991) is perhaps the most celebrated one in Zhang’s oeuvre.  While discussing Ju Dou, I did not comment upon Zhang’s use of interiors but he makes an association between the structure of an ancient dwelling and social dictate/ feudal structure. The transgressions, for instance, tend to happen in the open air away from Jinshan’s family mansion. This sense becomes much stronger in Raise the Red Lantern, which is set in the home of a wealthy man in the 1920s – a period called the Warlord Era. The only time the heroine is seen outside the structure of the mansion where she is housed is when she makes her way there for the first time, as a single girl just out of college. While discussing Ju Dou, I did not comment upon Zhang’s use of interiors but he makes an association between the structure of an ancient dwelling and social dictate/ feudal structure. The transgressions, for instance, tend to happen in the open air away from Jinshan’s family mansion. This sense becomes much stronger in Raise the Red Lantern, which is set in the home of a wealthy man in the 1920s – a period called the Warlord Era. The only time the heroine is seen outside the structure of the mansion where she is housed is when she makes her way there for the first time, as a single girl just out of college.

In the film Songlian, whose father has recently died and left the family bankrupt, comes into the wealthy Chen family, becoming Fourth Mistress of the household. Arriving at the palatial abode, she is at first treated like a queen. Gradually she discovers that all the mistresses are not treated equally and those most favored – usually the youngest – get the best treatment. The wife favored for the day receives a foot massage; the day’s menu favors her and a red lantern is hung outside her quarters at night. Songlian also discovers that there is much rivalry between the wives and, after initially suspecting Third Mistress (a former opera singer) to be her chief adversary, she finds Second Mistress to be more dangerous. Songlian has a servant girl named Yan’er but this insolent girl, she discovers, harbors the ambition of becoming Fifth Mistress. A favored wife is allowed to take liberties with the man but she also risk losing her place to a rival. Overall, the life of a favored wife is a good one but transgressions are dangerous. A pregnant wife is favored but if the intimation is false, she stands to be punished (32). Songlian, on her explorations of the mansion, discovers a secluded room on the roof where an adulterous wife was hanged in an earlier generation.

Zhang uses many of his characters as emblems for patriarchy. Songlian, for instance, is persuaded by her mother to consent to becoming Chen’s Fourth Mistress but we do not see her mother who is doing the persuading. Similarly, Chen is never shown except in long shot or as a shadowy figure in the bed with the women (33). His arrival and the bestowing of his favors are only announced through the ceremony conducted by servants. At the climax, the drunken Songlian betrays Third Mistress who is having a relationship with their doctor. The girl carried off into the room at the top where Songlian later discovers her hanged. The doctor is outside the purview of these brutal dispensations and Chen himself never makes an appearance. One could propose that the film is about a stable and oppressive system which is symbolized by the structure of the Chen family mansion. One observation made about the differences between the novel and the film is that while the novel caricatures Chen’s body as the site of female erotic fantasy the film makes Songlian’s body the focal point of all viewing subjects (34) and it becomes the site of Chen’s masculine conquest. My own proposal here is that since the ‘Master’ is turned into an abstraction not residing only in Chen’s person but in the family structure complete with its servants and traditions, Songlian’s body is being commodified for public/ patriarchal appeal. At the conclusion of the film Songlian becomes demented at her hand in Third Mistress’ death. This can be interpreted as a lament at the status of women in China, but I suggest that it is more ambivalent than such an interpretation would allow. There are numerous rooftop level sequences which dwell on the architectural beauty of the dwelling and, given the political significance of the structure, it appears a celebration. The extraordinary visual beauty of the film, I contend, makes the film a celebration of patriarchal structure and this finds support in my reading of the other two films.

Before moving on to next group of films by Zhang Yimou it would be helpful to examine a much earlier woman’s film made before the Communists came to power in 1949 to get a sense of the woman’s position in Chinese cinema before the Revolution. As already indicated, left-wing influence was strong in Chinese cinema and this suggests that the issue of women’s emancipation had been debated extensively. The film in question is Fei Mu’s Springtime in a Small Town (1948) and it is very highly regarded (35). This film is about a love triangle. Zhou Yuwen is married to a delicate man Dai Liyan perpetually in ill health. One day, Dai’s friend Zai Zhichen, who is now a doctor, arrives to stay with them. But Zai was once in a relationship with Zhou; the flame of passion is now rekindled and the two find themselves wishing that that Dai be dead. But Dai gradually realizes how much of an intruder is in his own home and attempts to kill himself. This brings the two to evaluate their position and understand the moral choices they are confronted with.

The film has several aspects in common with Zhang’s three films, which have just been discussed. It begins with a voiceover as does Red Sorghum but the narrator is the woman Zhou. The film deals with a relationship outside marriage as Ju Dou does and murder of the husband is also contemplated by the lovers. The woman feels desire for the other man rather than the husband (as in Red Sorghum and Ju Dou). When her husband Dai tries to claim his conjugal rights with Zhou, she spurns him gently. The woman feels jealousy when a younger woman is drawn to the man – Dai’s younger sister in this film and the maid Yan’er’s aspiring to become Fifth Mistress in Raise the Red Lantern. Lastly, Springtime in a Small Town treats tradition through the metaphor of ‘structure’. Zhou and Zai meet frequently on the crumbling city walls of the town, which comes to represent threatened tradition.

The similarities between Springtime in a Small Town and Zhang Yimou’s film pertain to the issues problematized rather than the resolutions opted for – repressed feminine sexuality, competitiveness among women over a man, patriarchal authority and tradition as a walled structure. At first glance we are led by the violence in Zhang’s film to believe that his critique is the more radical one because Fei Mu always opts for ‘compromises’. The husband is understanding and tries to remove himself from the scene and this leads the lovers to understand their transgression. The younger woman understands the older woman’s desire and the husband’s claims upon his wife eventually take precedence over those of the lover. But when we look at all the films more closely, we find that the violence in Zhang’s films does not arise of a more radical critique of tradition but out of transgressions going the distance and then being punished brutally, instead of a ‘compromise’ – where the justification for transgression is acknowledged but the presented opportunity forgone. The difference between the two filmmakers is not that one is more critical of patriarchy; both essentially accept it, although they acknowledge its iniquities. Zhang portrays it as more fearsome but this is also tantamount to celebrating its strength. It can be argued that in portraying the individual’s response to patriarchal tradition, Springtime in a Small Town allows him/her more agency than Zhang Yimou’s films do. Seen from another perspective, Zhang perhaps finds feminine sexuality to be more disruptive and threatening to patriarchal structure, thus necessitating its brutal suppression.

Critiquing contemporary society

The two films I examine in this section, The Story of Qiu Ju (1992) and Not One Less (1999) are both set in contemporary China. The first of the two films is apparently based on a true life incident. It is about a rustic woman whose husband Quinglai has been kicked in the groin by the village chief Wang on account of an altercation. Qiu Ju’s husband has offended the village head by ridiculing the man’s propensity to produce only daughters, not a son. After Qinglai is treated medically Qiu Ju complains to the local policeman Li about the incident. Li mediates and arranges it so that the husband receives compensation – for the cost of treatment and the wages lost. But when Wang makes over the money to Qiu Ju, he does it rudely and the woman feels insulted. Qiu Ju is clear that it is an apology she wants and not the money. Although she is in an advanced state of pregnancy she travels to the city with her sister-in-law, going to a higher authority on each occasion but the damages awarded are the same – money but no apology. She, on the advice of a sympathetic official, then employs a lawyer and goes to court but even that is futile.

The advice Qiu Ju now receives from policeman Li is to have Qinglan x-rayed. If the x-ray reveals injury, Wang can be charged with assault. At this moment however, she enters labor and it is only with her adversary Wang’s personal assistance that her child survives. Festivities are now held and she personally invites Wang, but he declines to come. At that moment, the results of the x-ray arrive and a broken rib is indicated. Wang is charged with assault and sent to jail for 15 days, a development Qiu Ju regrets; all she wanted was an apology and Wang also saved her life.

The first thing we notice about The Story of Qui Ju, especially after the earlier films is Zhang’s move towards ‘minimalism’. Where the earlier films dealt with violent emotions and conduct flamboyantly, Qui Ju is gentleness itself. At first, it looks as though Zhang is following a new aesthetic because his heroine’s stubbornness appears to go beyond the bounds or reason and merit irony but there is apparently more. Early in the film when Qui Ju gets a professional letter writer to draft her complaint, he asks her whether she wants a mild or a ‘merciless’ tone because the latter costs more. When she wishes to know what the difference is, he tells her that out of the seven ‘merciless’ complaints he penned, two led to executions and three people got life sentences. This seems like black humor but as we proceed, we understand that a ‘complaint’ is a serious matter. It is the basis on which people are charged with crimes; if the crime named is serious, the consequences could also be grave. One imagines what such ‘complaints’ against officialdom might have achieved in the Cultural Revolution.

The Story of Qiu Ju is made almost in documentary style but it comes across as a considerably softened up version of political/ social reality, not because it is untrue to the situation in 1990s China but because of the studied simplicity of those it is about. Qiu Ju is assisted at every step by people and officials. The manager of the place in which she stays offers her advice for free, a senior official in the city has her sent back to her lodgings in his car, a passerby advises her to dress like a city person not to be taken advantage of by ‘crooks’. She goes to court against the State on the advice of a State official, such a nice person that Qiu Ju is upset at having to sue him – until he assures her that no harm can come to him. When policeman Li’s efforts are of no avail and Qiu Ju goes above him, he admits his ‘incompetence’ without rancor.

On reflection we understand why the people in this film are so different from the three dealt with in the last section. If the people in Red Sorghum, Ju Dou and Raise the Red Lantern act largely in their own personal interests, those in The Story of Qiu Ju are fulfilling the social roles assigned to them – their actual persons being scrupulously kept out of the transactions at all times. We gradually realize that the film is really an allegory of collective life and its drama lies in the exception of two people acting ‘personally’. Qiu Ju pursues ‘justice’ but fails because the State recognizes the chief only as the State embodied while she sees him as Wang. The resolution therefore consists in Wang righting a wrong by going beyond what is required of him as a functionary of the State, and getting acknowledgment from Qui Ju. Qiu Ju’s own error consists in acting as an ‘individual’ rather than a ‘citizen’, in other words, exceeding her part in the collective life of the community.

The difference between the world of The Story of Qiu Ju and the worlds of three films from the last section, it can be proposed, lies in the former film contending with the Government as an omnipresent (yet invisible) structure. While ‘collective life’ involves the State at every juncture in the shape of officials, the political Government (i.e.: Party) itself is absent except as an invisible prevailing order. It may be noted here that Raise the Red Lantern has been read as a veiled critique of Communism as a dictatorial community – Songlian as the individual and Master Chen as the Government, the laws of the household paralleling those of the country (36). Although the Government frowned upon Raise the Red Lantern, there is little evidence that Chen’s household represents Zhang Yimou’s view of contemporary China. When Zhang does deal with contemporary China, the ‘individual’ is not the issue he is concerned with as much as the ‘citizen’, with the Government itself being entirely invisible except as ‘order’, which – judging from The Story of Qiu Ju – might even be metaphysical (37). The reader may wonder at this point whether this absence of ‘Government’ is a characteristic of films like Ju Dou and Raise the Red Lantern as well. While this is true, neither do these films convey the sense that life is governed by a scrupulous, omnipresent order.

The second film from the same category as The Story of Qiu Ju and also employing a quasi-documentary style is Not One Less (1999). This film is perhaps more sentimental although it offers the same discourse about the citizen, the State and the Government. The film is about a teenage girl Wei Minzhi who is entrusted with keeping a class of schoolchildren engaged during the teacher’s absence. She is given the instruction by the Mayor that she must hold on to all of them and there must not be even one less when the regular teacher returns but it so happens that she loses two children. The first loss is acceptable because the girl was selected for a specialist sports school. But the second – a boy – left because his family is in debt and he has to move to the city and earn a livelihood. Wei now enlists her pupils to help her raise money to go to the city but cannot find the boy. But, after several encounters with officialdom – in which those she meets are always considerate and scrupulous in doing their duties as officials or citizens – Wei gets a slot on a TV broadcast and her tearful appeal sees the lost boy making contact. This publicity draws the much-needed attention of the authorities to the condition of rural schools.

Not One Less is a ‘feel good’ film apparently made under censorship and it will be useful to compare it with another film about school children from a country with severe censorship issues – Abbas Kiarostami’s Where is My Friend’s Home (1987) from Iran which also uses a quasi-documentary approach. Both films have been internationally well-received with Not One Less winning the Golden Lion at Venice and Kiarostami’s film getting awards at Locarno. In both films there is an educational authority issuing directives. In Kiarostami’s film it is the teacher warning his pupils against not doing their homework while in Zhang Yimou’s it is the mayor, telling the temporary teacher not to lose even one child. Kiarostami’s film can be read as an allegory against authoritarianism: the protagonist has accidentally kept his friend’s notebook and the friend cannot therefore do his own homework, making him vulnerable to the teacher’s wrath. The boy therefore does his friend’s homework so that the latter is able to pass the teacher’s scrutiny. This resolution can be understood as implying the need for individuals to help each other out guilefully when confronted by the common tyranny of authority. Not One Less, in contrast, is about the citizen obeying authority in such a complete way that it transforms the present. Where Kiarostami’s film is about the individual coping with authority, Zhang Yimou’s is about the citizen assisting authority to make collective live better. The State may have been lagging behind in achieving its aims but the citizen’s involvement helps it improve, is the discourse. Zhang’s film does not have a message which can be understood as a critique and is an open endorsement of the State. It is not a film which is trying to get past censorship. As in The Story of Qiu Ju, politics and the Government are invisible in Not One Less. All that is visible is the State, which is an administrative collective engaged in improving the conditions of the citizen with his/her involvement (38).

The two films dealt with in this section were made when China was going through a period of ‘consumerism, commercialization, depoliticization and deideologization’ at a time when people had lost faith in grand ideologies (39) and this may account for their tendencies. But as we shall see, Zhang’s remaining films reflect the same characteristics and there is consistency in all his work.

Revisiting China under Mao

Zhang Yimou’s two films dealing with life in Mao’s China which are of pertinence here are To Live (1994) and The Road Home (1999). To Live is a sprawling film which begins in the KMT period and ends in the decade of the Cultural Revolution. Xu Fugui (Ge You) comes from a rich family but is a  compulsive gambler and loses all his property to the puppet master Long’er. Since he has knowledge of puppetry, the puppet master gives him a set of shadow puppets with which he earns his livelihood, giving performances. He and his friend Chunsheng are conscripted by the KMT but with their defeat by the Communists, Xu begins to perform for the revolutionaries. With the final victory of the Communists, Xu returns home to find that Long’er burned his house – once usurped from Xu – down and he is being shot as a saboteur. The story now moves a decade forward into the frenzy of the Great Leap Forward, when his son is accidentally killed in an accident by the local Party chief. When this man comes to give his heartfelt condolences, Xu discovers that the man is his old friend Chunsheng. compulsive gambler and loses all his property to the puppet master Long’er. Since he has knowledge of puppetry, the puppet master gives him a set of shadow puppets with which he earns his livelihood, giving performances. He and his friend Chunsheng are conscripted by the KMT but with their defeat by the Communists, Xu begins to perform for the revolutionaries. With the final victory of the Communists, Xu returns home to find that Long’er burned his house – once usurped from Xu – down and he is being shot as a saboteur. The story now moves a decade forward into the frenzy of the Great Leap Forward, when his son is accidentally killed in an accident by the local Party chief. When this man comes to give his heartfelt condolences, Xu discovers that the man is his old friend Chunsheng.

A singular fact about the film which has been ignored is the Xu’s transformation under Communism. Under KMT rule Xu is shown to be a profligate, squandering his last penny in the pursuit of pleasure. If Ge You plays Xu quite brilliantly and with a carefree swagger in the early parts of the film, after the Revolution Xu is a different man and it is as if psychology abandons him. He is, to be accurate, transformed from an individual (with agency) to a citizen upon whom history acts. In fact the only one in the Communist era who betrays a sign of a psychology – acting in private interests and not only being an ‘agent’ – is Long’er, who is executed.

The film is ‘critical’ of the violent political developments under Mao but misfortunes that happen are accidental and, as in Not One Less, people ‘mean well’ because they scrupulously live the collective life. They are never individuals pursuing private ends but citizens or agents of the State and part of the collective. There is no evidence of people acting as politics did not intend them to act – which is contrary to what The Legend of Tianyun Mountain and The Blue Kite conveyed. When the Cultural Revolution arrives at the end of the 1960s, a Red Guard Wan Erxi – with a physical handicap – courts Xu’s daughter Fengxia. One day, Xu receives information that Red Guards are tearing down his humble home but when he goes thither he finds it is Wan Erxi and his comrades repairing the roof and painting it. Chunsheng, still in the government, has now been branded a reactionary and a capitalist for reasons unknown. He visits immediately after Fengxia’s wedding to Wan to ask for Xu’s forgiveness, and to tell him his own wife has committed suicide and he intends to as well. It is as if suicide is the natural course for those out of favor but at the same time there is never any indication that what awaits them otherwise is worse.

Wan and Fengxia love each other and she becomes pregnant. Unfortunately there are complications and a doctor cannot be found because, as ‘intellectuals’, doctors are being persecuted. When a doctor is located, he is starving and they feed him buns to give him strength. But he drinks water thereafter and relapses into a semiconscious state. The water has expanded the seven buns to occupy enough space for forty-nine in the doctor’s belly. Fengxia therefore dies although her son survives to be taken care of by Wan and to carry the family forward into happier times.

Before going on to examine the other film The Road Home, a little more needs to be said about To Live. The first has to do with the continued absence of ‘politics’ in the film because the sense we get is of unexplained political commands being obeyed and rhetoric employed with no correlation between the action and the rhetoric. As an instance, the rhetoric invokes ‘rightists’, ‘intellectuals’, capitalist roaders’ and ‘reactionaries’ but since everyone is only an ‘agent’ – either a law-abiding citizen or an official performing his assigned role – there is an absence of category distinctions along the lines indicated by the labels (40). At the same time, there no questioning of the rhetoric either, or a sense that it is only instrumental. Where The Blue Kite allows for villains, To Live does not. The Cultural Revolution is treated as a mass affliction for which no one is responsible, and which passes. The happenings in the Cultural Revolution – as depicted – have the status of ritual which cannot even be described as ‘political’ because supposed ‘political decisions’ are so randomly applied. Party decisions are so unfathomable but their consequences so extreme that politics might even be understood as the handiwork of the Gods.

The Road Home (1999) does not, at first sight, appear to have anything to do with Mao and the Party. It begins in the present as in Red Sorghum with a male voice telling a story. This time the occasion is the death of his father who died some distance from his home and has to be brought back. The story the narrator tells is the love story of his father Luo Changyu and mother Zhao Di. Luo Changyu was an unemployed city boy who was ‘signed up’ to serve as teacher in a village and was looked up to by everyone. Zhao Di fell in love with him but, after a brief courtship, Luo was summoned by the Government and he went away, promising to return. Zhao, being heartbroken, fell grievously ill until Zhao retuned. But Zhao had returned without permission and the two were not allowed to be married for two more years. In the present, the father has to be brought home on foot as is the custom in these parts, so that the father’s spirit will always know the way back home.

There are several significant features in the film and the first has to do with the village being idyllic and set in the ‘mountains’. Life is not particularly hard and the folk adore the schoolmaster, competing with each other to invite him home for a meal or two. There is no conflict within the village – everyone is a citizen transacting directly with the city boy ‘signed up’. There has been some speculation about what the schoolteacher and his recall by the Government may represent politically and one viewpoint is that it refers to the Anti-Rightist Campaign of the late 1950s. But let us consider when the events might have been set. The film begins in the present with the narrator – who drives an expensive SUV – apparently in his mid-thirties. Assuming that his parents married around thirty-five to thirty-eight years ago, this puts their romance in the early 1960s. This, and the circumstances of the city boy in the village, suggests that the schoolteacher Luo Changyu corresponds to one of the ‘Rusticated Youth’ or ‘Sent down Youth’ (zhiqing) about whom much was written.

After the People’s Republic of China was established, in order to resolve employment problems in the cities, starting in the 1950s youth from urban areas were organized to move to the rural countryside, especially in remote towns to establish farms. In 1955, Mao asserted that ‘the countryside is a vast expanse of heaven and earth where we can flourish’, which would become the slogan for the ‘Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement’. Liu Shaoqi instituted the first ‘sending-down’ policy in 1962 to redistribute excess urban population following the Three Bad Years and the Great Leap Forward but Mao later modified its intent. In 1966, under the influence of the Cultural Revolution, university entrance examinations were suspended and until 1968, many students were unable to receive admittance into university or become employed. The chaos surrounding the Revolution from 1966 to 1968 caused the Communist Party to realize that a way was needed to assign the youth to working positions, to avoid losing control of the situation that Mao had initiated. On December 12th, 1968, Mao directed the People’s Daily to publish a piece entitled “We too have two hands, let us not laze about in the city”, which quoted Mao as saying “The intellectual youth must go to the country, and will be educated from living in rural poverty.” from 1969 onwards many more youth were rusticated and the total number rusticated between 1962 and 1978 is estimated at seventeen million (41). These young people – most of whom had received little education – suffered great hardships and were often met with local hostility. Only after 1978 were they and their families permitted to return to their original homes. It would appear that Luo Changyu is a Rusticated Youth although the circumstances arranged for him by The Road Home are less harrowing. The word ‘home’ is deliberately imparted a different significance in the film but it may also suggest the post-1978 return of Rusticated Youths.

Judging from the films not only described in this section but also in the last one, Zhang Yimou seems more a propagandist for the State rather than a dissenting artist; his films set post-1949 suggest implicitly that the objectives of the Communist Party were largely achieved. If a social utopia is a system in which everyone performs his/her role neither deficiently nor to excess but correctly, Communist China is a collective utopia (42) – with the only obstructions to universal happiness being ‘epidemics’ like the Cultural Revolution – and Zhang is virtually ‘willing’ it. Since some of his other films – like Raise the Red Lantern – have even been understood as works of dissent, a reconciliation of the two Zhangs is evidently needed.

In discussing Raise the Red Lantern it was observed that the film was more ambivalent than was generally supposed; while dealing with the oppression of women by patriarchal tradition the film employed an aesthetic that tended to be celebratory. This reading was supported by Ju Dou in which the punishment of the lovers for sexual transgression is also treated ambivalently and Red Sorghum in which it is the grandfather’s story which is heard and transmitted, although the grandmother is nominally at the film’s centre. As already indicated, Red Sorghum finds an echo in The Road Home, in which it is a male voice that relays the central love story. In To Live the history of the family is also continued through its male line. All these films conclude with the restoration of social order and this provides us with a clue as to how to read them – regardless of when each of them is set.

Overall, the sense to be gathered is that under KMT administration social order is implicitly patriarchal and feminine desire is, effectively, the disruptive force. In Red Sorghum, Raise the Red Lantern and Ju Dou, feminine desire causes the ‘disturbance’ which gets the narrative moving. But when the Communist utopia is ushered in, the resultant order is still patriarchal and feminine sexuality remains a threat. In The Story of Qiu Ju, the woman’s implacability (43) – rather than the chief’s act of violence – is connoted as the disturbing element. It is the heroine’s desire for the schoolteacher in The Road Home that the Government keeps at bay in the service of order/ discipline. Raise the Red Lantern was banned but this was apparently not because of any explicit political content but because of interpretations – which the filmmaker has alleged exceed the film’s intentions (44). Zhang’s films in which the sexed woman is punished pertain to the KMT period – before the utopian Communist State was ushered in. In the Communist period, there is no discernible punishment of this kind because collective life is quickly reestablished in every case. I therefore propose that a relationship can be detected between Zhang’s sense of a utopian order and the suppression of feminine sexuality. This proposition can now be examined in the context of Zhang’s historical/ mythological extravaganzas.

The Empire strikes back

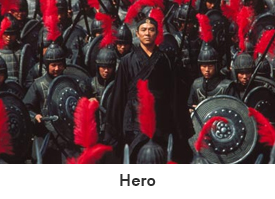

The last films to be looked at in this essay are fanciful recreations of China’s imperial past, the first of the films examined being Hero (2002). This film tells a story from the warring states period in  the Third Century BCE and involves the first Qin Emperor Qin Shi Huang who finally unified China, and the assassins who tried to kill him. The film, which was a worldwide hit is less a historical film than a mythological with martial arts (wuxia) as a major component. The King, who has survived an attempt on his life from three assassins named Long Sky, Flying Snow and Broken Sword allows no one within a hundred paces of himself but he now grants the privilege to ‘Nameless’, the prefect of a small jurisdiction who claims to have killed the three assassins and produces their weapons as evidence. the Third Century BCE and involves the first Qin Emperor Qin Shi Huang who finally unified China, and the assassins who tried to kill him. The film, which was a worldwide hit is less a historical film than a mythological with martial arts (wuxia) as a major component. The King, who has survived an attempt on his life from three assassins named Long Sky, Flying Snow and Broken Sword allows no one within a hundred paces of himself but he now grants the privilege to ‘Nameless’, the prefect of a small jurisdiction who claims to have killed the three assassins and produces their weapons as evidence.

The rest of the film is largely in a series of flashbacks pertaining to Nameless’ encounters with the assassins, the assassins’ relationships among themselves and interludes in which the King and Nameless talk to each other. Gradually, it comes out that Nameless himself is an assassin to whom the others submitted because he was felt to possess the greatest skills. This submission was essentially to get him to within striking distance of the King, which is where he finds himself now. These facts are not revealed by Nameless but discovered by the King who confronts his would-be assassin and offers to die. Nameless now reveals that Broken Sword and Flying Snow, who were lovers, are now both dead. Broken Sword had finally arrived at the view that the King should not be killed since only he could unite China (‘all under one heaven’). This led to Flying Snow fighting and killing Broken Sword accidentally, thereafter taking her own life. Nameless can now kill the King but the latter’s willingness to die in the cause of national unity convinces Nameless of his vision and he forgoes the opportunity presented. The King – at the behest of his courtiers – now reluctantly orders Nameless’ execution and his would-be assassin is granted a hero’s funeral.

There are several factors that invite attention in the film and the first has to do with there being no villains. Everyone is fulfilling a moral purpose based on his/her convictions and self-interest is never a consideration. Codes are strictly followed at all times even when enemies deal with each other and the single purpose towards which the story moves inexorably is the unification of the nation in the will of the Emperor. As this might suggest, the Confucian notion of self-improvement through emulating the teacher – which is central to a martial arts film from outside the PRC like Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) – is conspicuous by its absence (45). All heroes are given near equal capability as a way of not valorizing individual achievement, but the heroes choose to acknowledge the King – except Flying Snow, who dies by her own hand. She wished to avenge her father, a victim of the King of Qin but she killed her lover mistakenly – engaging him in combat when he wished to submit to the King but wished that no harm befall her.

The division of characters into heroes and kings is also true of the epics like The Iliad but where the hero is usually greater and favored by the gods in the epics, Hero does differently by making the King supreme. A hero can decimate an entire King’s army but, when brought up against the King’s will, he submits to it because the King is the agent of the only acceptable order. The King’s will is so omnipotent that each arrow of every soldier obeys his command. The arrows shot at Nameless by hundreds of soldiers are so accurate that they make a ‘shadow’ – a bare spot marking out his shape – on the wall before which he stands.

There is little doubt that Hero was undertaken as a nationalist project, a eulogy of China’s first nation-builder. The first Qin Emperor has often been castigated by historians for his brutality but he was also responsible for introducing the characteristics of government, economics, commerce and culture that we associate with modern China – including the centralization of state power. The Qin emphasis on legalism challenged the Confucian moral and political order and was resisted by the Confucians. There are also parallels between the first Qin Emperor and Mao because he ushered in a ‘Cultural Revolution’ by burning classical texts, notably to abolish the tendency to disparage the present by praising the past (46). Like Mao, he placed his emphasis on practical learning rather than theory which is why he burned classical texts.

Despite the obvious political implications, critics have been divided on the film. While some – like those in Taiwan – have seen it as a ‘selling out’ on Zhang’s part (47), others find the film to be too complex and multi-layered to be thus interpreted. An argument in support of this ‘complexity’ is that the King being pressurized to execute Nameless is a sign that the King himself has little freedom (48). This is dubious because autocratic political leaders – Stalin and Mao included – often used the pretext of ‘public demand’ (49) to mitigate their own responsibility for their most brutal acts. The ploy of the King’s regret – as his willingness to die – is being used by the film to make him more worthy of eulogy.

Rather than being a departure for Zhang, one finds much continuity between Hero and his other films. Firstly, every character in the film is identified with his/ her role, be it rebel or King, i.e. implicated entirely in collective life although this is in the future nation. No one acts except for the most self-effacing reasons and this naturally rules out villains. Secondly, the King’s inaccessibility finds correspondence in the invisibility of the Government in films like The Road Home and the impenetrability of Party decisions, a characteristic noticed even in films by other filmmakers in the 1990s. Thirdly, each arrow submits in its trajectory to the King’s will which is comparable to every aspect of social life turning out exactly as the Party ordains it – a utopia already achieved, as contemporary China is portrayed in Not One Less. Lastly, the single element which declines to submit to the King and his vision is Flying Snow who also exhibits jealousy, and acts out of it. Flying Snow and another woman character Moon introduce a motif outside that of the ‘nation’ which is feminine sexuality, once again disruptive. This, as is apparent, finds correspondence in The Story of Qiu Ju, The Road Home as well as the films set in the KMT era.

The second film House of Flying Daggers (2004) is set in a ‘corrupt’ period in Imperial Chinese history, the last days of the Tang dynasty (9th century CE) but, as if it would be improper to portray Imperial China as ‘corrupt’, agents of the Empire perform their tasks scrupulously. While the story of the film is a web of complications, we can nonetheless identify a few characteristics. There are two opposing sides in the film, the Empire and the rebels with Zhang taking sides with the Empire since his protagonist is in pursuit of the rebels. Secondly, while the introduction of two sides means that there is no eulogy of the Emperor as in Hero, the protagonist is unwavering in his duties – laid down as part of a larger design – until he is distracted from the path by his love for a woman who is on the other side. When love plays a part in the story, therefore, its purpose is disruptive. Love is an obstruction in the path of the Empire because agents of Imperial design are distracted by it.

Both House of Flying Daggers and the last film Curse of the Golden Flower (2006) allow the hero more agency than Hero allows him but they are both set in the declining years of the Tang Dynasty. This is significant because the Tang Dynasty broke up into the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms in the early part of the 10th Century CE. If we say that Hero is about individual heroes submitting to the monarch in the service of a unified China, these two films suggest its converse: intrigue and individual heroism as a prelude to a divided China.

Curse of the Golden Flower is a costume drama which is based on a play by Cao Yu from the KMT era, a family melodrama involving incest named Thunderstorm (1934) which created a scandal. Zhang’s film transposes this story to the last years of the Tang Dynasty and it now involves the happenings in the royal household. It introduces some ‘Shakespearean’ motifs because the sons are plotting against the Emperor but, perhaps characteristically, they are motivated less by a desire to usurp the Crown than by their love for the Empress, who is not only in an incestuous relationship with her step-son but is also being slowly poisoned on the Emperor’s orders. The Princes are all eventually killed and the Emperor reigns supreme. Order is restored on the day of the Chrysanthemum Festival when the blood-soaked palace grounds are cleaned up swiftly and they reacquire their customary dazzle.

House of Flying Daggers and Curse of the Golden Flower are apparently not intended as nationalist projects because they deal with periods of imperial decline but Zhang Yimou’s approach remains consistent. In the first place the films unfailingly uphold the Empire; in the latter film it is the ruthless Emperor Ping who rules supreme although the domestic melodrama Thunderstorm (on which it is based) did not conclude with the patriarch’s triumph. Although the Emperor is ruthless, brutal and a degenerate in Curse of the Golden Flower his victory over the others is celebrated because his rule means ‘order’.