|

A popular media campaign for a nationwide drive to clean the country uses a simple but effective graphic mode: strong black lines delineate the iconic Gandhi with his charming tooth-less grin and the rimless round glasses moving straight to a winding path on which the footsteps of the Mahatma are etched, then to a vat into which garbage collects, an Indian style “”shouchalay”or latrine, with a tap and a buckets and finally to the culminating shot a neat picturesque city with near-empty roads with a car and two happy cyclists. The appeal of the campaign, an initiative of the new government (encapsulated in its catch phrase ”swacch bharat”), is unambiguous: the mission “clean India” is both strikingly original and yet has its roots in India’s nationalist past, one that is associated with the Father of the Nation, a father whose personal and political ethic could be summed up as cleanliness as close to godliness.

Does the name of M.K. Gandhi have any appeal to the current generation which has often regarded the period of nationalist struggle for independence from colonial rule merely as a chapter in their history books?. Yet, interestingly enough there has been a return of bapuji thanks to the stupendous success of his screen representation in the film Laage Raho Munnabhai, as a benign but canny conscience–keeper who acts as friend, philosopher and guide to Munnabhai, the rogue with a golden-heart.

So for young India, fed on Bollywood and sold on the twin mantra of development and anti-corruption, the appeal to Gandhigiri does carry valence.

The campaign also has a line from a song “jodi tor daak shune keu na ase tobe ekla cholo re” a Bengali song sung with a markedly non-Bengali accent. For those not familiar with the tune it would be difficult to identify it as a Rabindrasangeet, a song whose lyrics were composed by Rabindranath Tagore. It happened to be one of the songs that M.K Gandhi found to his liking, perhaps because of its content “ if no one were to respond to your call, you must proceed alone” since it fitted snugly with Gandhi’s philosophy of politics, i.e. to transform lives by creating active precedents and not empty preaching. Yet, incorporated in a campaign which is an appeal to the collective conscious to keep one’s surroundings free from garbage, dirt and pollution, it is reduced to a single gesture which is divested of its other significance of developing the moral fibre.

Even if one were to discount this reading it is obvious that the campaign functions at twin modes: that of acknowledgement of the figure of Gandhi and an erasure of that of Tagore. Not only is Gandhi seamlessly absorbed in the current discourse of Swachh Bharat that pays lip-service to Gandhi it is also an attempt to wipe out the role of Tagore in advocating self-determination and self-reliance even to the effect of being a lonely crusader. It may be worth recalling that long before Gandhi appeared on the national scene, it was Rabindranath Tagore who had given a clarion call to the nation to be self-reliant in his lecture Swadeshi Samaj later published an essay by the same title in 1905. The original impetus behind the highly charged polemics of the lecture was to find the solution to a severe water-crisis by suggesting that instead of mendicancy to colonial rule the more effective mode would be to tap indigenous resources of a resilient community.

But surely , it would be grossly unfair to the media, ad-gurus to pack in all this in a campaign whose appeal is quite clear and limited. Yet, like all semiotic systems the campaign can have resonances which are evidently not part of its avowed intention. Here too, the juxtaposition of Gandhi and Tagore, in the metonym of his song, sets me thinking about the relationship between them.

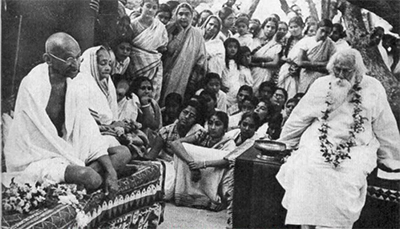

In 1915, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned to India from South Africa. One of the first places that he decided to visit was Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan ashram. This institution was created on the ideals of the ancient Indian forest hermitages or tapovan and its core was an alternative school; in 1921 Tagore conceived of a world centre for culture called Visva-Bharati in the very same premises. On the occasion of the centenary of Gandhi’s return to India, this essay explores the engagement between Tagore and Gandhi in the specific context of the history of the Santiniketan institution revisiting some of the key moments of collaboration and conflict between the two.

Gandhi and Tagore ‘s Santiniketan ashram: early visits and impact

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned from South Africa to India in 1915. Before he engaged actively in politics, Gandhi travelled widely, visiting those Indians he had known, primarily through epistolary exchanges, during his South African sojourn. Among them was Rabindranath Tagore. In December 1913, Tagore had written to Gandhi expressing his support for the latter’s protest  movements in South Africa in moving terms, stating that it was "steep ascent of manhood, not through the bloody path of violence but that of dignified patience and heroic self-renunciation." (Tendulkar,145). movements in South Africa in moving terms, stating that it was "steep ascent of manhood, not through the bloody path of violence but that of dignified patience and heroic self-renunciation." (Tendulkar,145).

On January 2, 1914, C.F. Andrews and W.W. Pearson, two Christian missionaries who had dedicated themselves to the cause of India’s nationalist struggle, went to South Africa to meet Gandhi. It is likely that Gandhi received firsthand information about Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan ashram experiment about an alternative community, centering on pedagogy, from C.F. Andrews. This must have appealed to Gandhi who had set up two community-living experiments in South Africa, The Phoenix Settlement (1904) and Tolstoy Farm (1911).

Once it was decided that the members of his South African community would relocate to India, it was important to find a place most congenial to the boys who had been used to an alternative mode of living. Mohandas Gandhi sent the students of the Phoenix School, under leadership of Maganlal Gandhi, to Tagore’s ashram in November 1914. The group stayed on till 3 April 1915. (Tendulkar,156). In a letter to Gandhi, Tagore thanked him for sending the boys, stating that he was hopeful that this would form a “living link in the Sadhana of both of our lives.” (Bhattacharya 44)

Gandhi and his wife Kasturba arrived in Santiniketan on February 17, 1915 and though Tagore was away, they were given a grand welcome by the members of the ashram community. A detailed account of the ceremony is available from an article written by Sudhakanta Roychoudhury, a student of the ashram-school. Roychoudhury recounts that the guests walked along pathway created especially for them to enter the ashram premises; they were welcomed with flowers and sandal paste was applied on the forehead and later their feet was washed ceremoniously; esraj and sitar were played as accompaniment to a welcome song by Bhimrao Shastri, the famous classical musician; finally they were led to a dais, made out of mud in the shape of a lotus—four earthen-ware pots filled with water …were placed at four corners of this dais along with lighted earthen diyas (Pal, 88) [ Translation mine]

Gandhi was deeply impressed with this aesthetic ceremonial welcome rooted in the traditional Vedic or Sanskritic mode. He identified this as the authentic Indian tradition as opposed to the borrowed western one. His response is worth quoting at length:

I am particularly happy to find that you have arranged for the reception in the Indian manner. …. We shall grow up in the beautiful manners and customs of India and, true to her spirit, make friends with nations having different ideals. Indeed, through her oriental culture India will establish friendly relations with the … Western world. Today I have become very thick with this ashram in Bengal, I am no stranger to you." (Tendulkar, 160)1

Though his visit was cut short by the news of the death of his Indian mentor, Gopal Krishna Gokhale’s death (Gandhi rushed to Poona) he returned soon after in the 2nd week of March. This time Tagore was present. On the 10th of March Gandhi met the teachers of the ashram school and had discussions pertaining to education. In his diary he wrote ‘Went round with Sanitary Committee. No end of filth.’ (Pal, 89). On the next day he met the students and spoke to them to start experiment not only in keeping the premises clean but also cooking their food.

Tagore’s biographer Prasanta Pal writes that Gandhi’s suggestions created division among the ashram members. Charles Andrews, William Pearson, Nepalchandra Ray, Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhayay were in favour of students’ self-reliance in all matters, while there was opposition to the idea from among other teachers and staff. Gandhi, a shrewd observer, realized that the conflict needed to be resolved and addressed teachers and students in different gatherings. Rabindranath Tagore was present in the meeting to lend his tacit support to the Gandhian programme. However, it is not known whether Tagore ever intervened in any significant way in its implementation.

Perhaps Tagore knew that many of his teachers were skeptical of Gandhi’s views about self-reliance since the time given to cooking and cleaning would distract the students from the pedagogic program of the ashram. There was consternation among the parents/guardians of the students who began to openly voice their opposition to the project of self-help and also threatened to withdraw them from the school. Given this resistance, it is not surprising that the Gandhian mode did not quite take off in Tagore’s Santiniketan ashram. However, it was in Gandhi’s honour that 10th March was assigned as the annual day of ritualistic spring cleaning in which students and faculty members participate.

Though Gandhi continued to visit the Santiniketan ashram in the early 1920s it was during this time that Tagore began to voice his opposition to the former’s politics of Non-cooperation. Tagore’s opposition was accentuated by his perception that the Gandhian programme was inimical to his new venture, the Visva-Bharati, which he originally conceived as a centre for culture and higher learning.

Against Gandhi? Tagore’s anxiety about Visva-Bharati

Tagore’s aspirations about a world centre of learning and culture is articulated in a letter, dated 11 October 1916, from Los Angeles and addressed to his son Rathindranath. Rabindranath Tagore wrote that he “wanted the Santiniketan school to be the link between Bharat [India] and the rest of the world. It is there that the centre devoted to the pursuit of universal humanist studies concerning all races should come up.” It is significant that his vision of India’s relation to the world through intellectual and cultural exchanges was posited as a counter to the “lethal serpentine coils of nationalism” (Thakur 70). Between 1916 and 1921 Tagore’s mounted scathing criticisms of nationalism in his lectures, correspondences and essays. In 1916 Tagore gave a series of public lectures in Japan and America on nationalism denouncing it as the end-product of a certain form of western modernity, characterized by xenophobia, aggression and coercion; in Tagore’s astute political analysis nationalism was an ideology that fed into systems of power which manifested itself as colonialism and capitalism. (Tagore ‘Nationalism in the West’ 419-35). One of the ways to counter and resist such divisive forces was by forging international links among the best creative and scholarly minds of both East and the West. Gradually he began to think of creating in Santiniketan a centre, which he would later name Visva-Bharati, which could serve as a haven. Visva-Bharati, I would argue was integral to his vision of ‘decolonization’ which went beyond ‘nationalist frames.’ The foundation stone for this institution was laid in 1918 and its formal inauguration took place in 1921. This was also the time when he was most vocal about Gandhian politics of Non-cooperation.

Tagore’s famous essay against Non-cooperation, addressed to C.F. Andrews, was published as three open letters, in the Modern Review of May 1921. Though the thrust of these epistles is to challenge the very moral principle and efficacy of Gandhi’s political program, there is an allusion to his own efforts to create a centre of learning and culture in Santiniketan which would unite the East and the West. This becomes clear in the following excerpt:

‘What irony of fate is this that I should be preaching cooperation of cultures between East and West on this side of the sea just at the moment when the doctrine of non-cooperation is preached on the other side.’ (Bhattacharya 58).

It is evident that Tagore was alarmed at what he perceived as the negative effect of Non-co operation, cutting off India from the rest of the world. He found Gandhi and his politics inimical to his own enterprise of a critical cosmopolitanism which he had hoped to initiate in Visva-Bharati. It was to fulfill this vision that he invited, among others, the famous Indologist Sylvan Levi and the art-historian Stella Kramrisch to Visva-Bharati in its initial, formative stages.2 The letters addressed to his friends and close associates contains direct or indirect references to this anxiety bordering on animosity. In a private conversation with Leonard Elmhirst, an Englishman who was to become his friend and ally, Tagore spoke candidly about his response to what he considered an alarming situation when he returned from his tour of Europe and the US in 1921:

I found that nearly the whole of my staff at Santiniketan had come under the direct influence of a political programme. They were so enthusiastic about the idea of Swaraj and non-cooperation that I realized what a struggle I would have to persuade even a handful of them to think in longer educational terms about the future. I wanted them to look beyond the immediate political horizon and not to be hemmed in by narrow nationalist ideas that were already out of date (Elmhirst 8)

Indeed, many of the prominent ashramites—Kshitimohan Sen, Nepalchandra Ray, Kalimohan Ghosh and Vidhushekhar Bhattacharya became deeply involved with Gandhian Non-cooperation.. In the period between 1920 and 1921, Tagore was infused with a strange zeal to protect and nurture his fledgling institution, against what he perceived as forces which were capable of destroying it. He did not miss an opportunity to categorically condemn non-cooperation and its divisive intentions. Gandhi came to meet Tagore in Jorashanko on 8th September 1921 with a personal appeal for support. Though it is customary, even among scholars, to say that the meeting was in camera, an account does in fact exist. In his book Poet and Plowman, Leonard Elmhirst recounts that Tagore spoke to him in detail about the visit stating how inflexible he was in his opinion about not supporting the Non-cooperation or Swadeshi:

…the whole world is suffering today from the cult of selfish and short-sighted nationalism… I have come to believe that, as Indians, we have much to learn from the West but we also have something to contribute. We dare not therefore shut the West out. But we still have to learn among ourselves how, through education, to collaborate and achieve a common understanding. (Elmhirst, 6)

Tagore was vehemently opposed to Gandhi’s appeal to support the students’ boycott of government schools and enlist in the scheme of national system of education. His argument, refuting Gandhi’s scheme, encapsulates his ideal for Visva-Bharati “I don’t yet believe in your national schools. They have too limited an objective. That is why I am inviting scholars from all over the world to come and help and at the same time to learn something from the creative aspects in our culture.” (Elmhirst, 7). It is evident that in 1921, for Tagore, Visva-Bharati crystallized ideas/ideals which existed on the opposite pole from the Gandhian political programme. The document that best expresses Visva-Bharati’s international cause is its Memorandum of Association (1922) which stresses that one of its aims is to

seek to realize in a common fellowship of study the meeting of the East and West and thus ultimately to strengthen the fundamental conditions of world peace through the free communication of ideas between the two hemispheres. (Emphasis mine)

Yet, by the mid 1930s Tagore, an old, tired man in his seventies, disillusioned by the lack of enthusiasm among his countrymen to the cause of his institution, turned towards Gandhi for help, on the advice of their common friend Charlie Andrews. In a letter dated 12 September 1935, Tagore confessed how “constant begging excursions with absurdly meager results added to the strain of my daily anxieties” stating also that he knew of “none else but yourself” whose words would induce the wealthy Indians to recognize the worth of his institution and be generous with funds. (Bhattacharya 162) Gandhi’s quick response that he would strain “every nerve to find the required money” (Bhattacharya 162) must have been reassuring. True to his word Gandhi raised money from the prominent business community in Bombay and sent a cheque of Rs 60,000 (Bhattacharya 163) and hoped this would give Gurudev a respite from his expeditions to raise money. However, Gandhi expressed his reluctance to be a Life Trustee or Pradhana in 1937 on grounds that he could not be expected to finance the institution; this letter caused heartburn and a quick, terse rebuttal from Tagore. This did not put an end to their exchanges or visits. It was at the time of Gandhi’s departure from Santiniketan on 2 February 1940, that Tagore sent his letter making a fervent appeal to “accept this institution under your protection” because “Visva-Bharati is like a vessel which is carrying the cargo of my life’s best treasure.” (Bhattacharya, 178). Gandhi, deeply moved by this plea made a promise to Tagore to ensure the continuance of the institution. He fulfilled his role of a guardian after Tagore passed away on 8 August 1941.

Honouring a promise: Gandhi’s efforts to preserve Visva- Bharati

Visva-Bharati authorities were apprehensive, quite correctly, that after the passing away of Rabindranath Tagore, the revered founder of the institution, the source of funding might dry up completely. Hence it became imperative to tap other resources: this included government aid and public fund raising. One such attempt was through the Deenabandhu Andrews Memorial Fund, named after Charles Freer Andrews, (usually referred to as ‘deenabandhu’ which meant “friend of the poor”) who passed away in 1940. Since Andrews was intimately linked with the Santiniketan ashram school and Visva-Bharati, it was assumed that a Memorial in his honour would include the nurturing of the institution. Gandhi took a special initiative for this fund raising since Charles Freer Andrews was his close friend. Irked by the news that donations were not forthcoming Gandhi went to Bombay himself and appealed to the community of businessmen. Following this a sum of Rs 5,00,000 was raised (VB News June 1942 156) and Gandhi entrusted Messers Bachraj & Co. as the treasurers of the Andrews Memorial Fund.

Gandhi’s decision not to disburse the money immediately, in all likelihood, stemmed from his dissatisfaction with the proposed plan of utilization of the money (the lion’s share of Rs, 4,00,000 was to be used for stabilization of Visva-Bharati) which was drawn up by the Samsad with very little constructive thinking about paying homage to Deenabandhu Andrews. 3 (VBP Image, 188). The Visva-Bharati authorities, recognizing the crisis, held a meeting on 12 August 1945 and made substantial revisions to the original plan following the draft made by Marjorie Sykes. This included the building of the Deenabandhu Bhavana for a fuller contact and understanding between India and the civilizations of the west. Hence it would “encourage scholars and students from the west…. for a study of some aspect of Indian culture, while at the same time making their own contribution to the life of Visva-Bharati” (VBP Image 199)

It can be surmised that this proposal met with Gandhi’s approval since he felt was in keeping with Gurudev’s vision of Visva-Bharati; there was a green signal to disburse the funds. On 18th December 1945 Gandhi visited Santiniketan; this was his first visit after the passing away of Rabindranath Tagore. The ostensible purpose was to lay the foundation for the Andrews Memorial hospital. On the following morning, Wednesday on which the traditional common prayer at the Mandir is held, Gandhi spoke of Tagore’s role as a messenger of peace.

That evening the heads of the various departments and prominent ashramites—Nandalal Bose, Kshitimohan Sen, Indira Devi, Krishna Kripalani and Rathindranath Tagore met Gandhi in an informal conference to consult him about the problems facing the institution him and to seek his guidance. (VB News February 1946 38) Gandhi’s response to the crisis of leadership and motivation was in many ways typical; he stressed on the need for ‘tapascharya’ as the mode through which the ashram members could carry forward Gurudev’s thought and work. On the issue of finances he went on to say, “I am convinced that lack of finances never represented a real difficulty to a sincere worker. ….. the difficulty lies somewhere else rather than in the lack of finances. Set it right and the finances will take care of themselves”. (VB News February 1946 39)

This is not merely a standard Gandhian iteration, an assertion of the value of and need to practice austerity. In this context it is also the voice of the ‘guardian’, ethical and astute in his understanding that the institution’s plea for more money, needed for infrastructure, and for expanding settlement was a definite move away from Tagore’s ideal. One can only speculate that Gandhi would perhaps have ensured a continued financial aid for Visva-Bharati as well been a vigilant presence, guiding the authorities for another few more years. His assassination in 1948 spelt a doom for the nation and the institution.

Preserving a shared dream of decolonization? Gandhi and the Santiniketan ashram

Why did Gandhi take so much effort to ensure the future of Tagore’s institution? The obvious answer is that he had given his word to Tagore and was honouring this promise. Let me suggest that a symptomatic reading may reveal reasons which go beyond the occasional. It is evident that for Gandhi the ashram, both as an idea and an institution, held a special appeal; once he returned to India with many of his South African fellow satyagrahis, he found it necessary to set up a community-living system calling it the Satyagraha Ashram (1915). In Ashram observances in action (1932) Gandhi states that the ashram, a term which he used in hindsight for his South African community experiments, was “a community of men of religion” where religion signified a spiritual bond between members (Gandhi 3). He stressed on the commitment to an unostentatious, non-acquisitive lifestyle in expression of solidarity with the wretched-of-the-earth. He incorporated these ideals into his understanding of the original meaning of ashram--- the disciplined labour of the ascetic. Some of the praxis which formed the basis of the community was a frugal living and manual labour—cooking, sanitation, fetching water were all done by members of the community. (Gandhi 4). The changes that he wished to implement in the Santiniketan are expressions of this idea of theashram. (Emphasis added).

Tagore’s idea of the ashram, in contrast, was organized around a vision of the education of the young as a joyous, creative learning process in harmony with Nature. The aesthetic—in the form of music, dancing performance and visual art, was integral to Tagore’s moral and spiritual vision of human development. It would not be entirely reductive to argue that tapas or ascetic rigour characterizes Gandhi’s idea of the ashram while ananda or joy can be identified as the core of Tagore’s concept.

In spite of these conceptual differences Gandhi developed a great fondness for Tagore’s Santiniketan ashram often choosing to come and spend time there. Tagore had chosen to build his ashram school in the sprawling 20 bighas (8 acres) that originally belonged to the Zamindars of Raipur, in Birbhum. It was imperative for him that the ashram be located away from the metropolis. The city, as Tagore argued, was a colonial construct, built with crude commercial interest in mind. It was an artificial space that was not in contact with Nature. In the context of the Santiniketan ashram, Tagore created the Nature he wanted through forestation; he planted Mango, chhatim and other tall shady trees turning the ashram into a soothing green spot amidst the arid, landscape of Birbhum. It is likely that Santiniketan or the ‘abode of peace’ held its special charm for Gandhi for its ambience but also because it embodied an attempt to imagine and bring into existence a mode of living which provided an alternative to the one created by colonial rule.

Since one of the ways through which colonization operated by was creating, for the colonized, a violent rupture with its own the past, it became an imperative to challenge and resist this by positing alternatives that could be traced to traditions, often by reinventing the past. Indigenous modes were held up as exemplary alternatives to colonial discourses and forms of ‘modernity.’ Tagore’s idea of the ashram as a community centered around pedagogy was precisely an attempt to create such an alternative which traced its roots to an ancient Indian past, often re-invented through reference to the Upanishads, myths, epics and other literary texts. The forest–hermitages or tapovan of ancient India served as the model for Tagore’s own ashram. In his essay ‘My School’ he writes in a nostalgic mode about such ashram–schools of ancient:

These places were neither schools nor monastries in the modern sense of the word. ..There the students were brought up… in the atmosphere of living aspiration… Though they lived outside society, yet they were to society what the sun is to the planets, the centre from which it received its life and light. (Tagore 395)

Within five years of his return to India, Gandhi, activist-lawyer who carved his career protesting against British apartheid in South Africa would emerge as the new leader spearheading a mass movement against colonial rule. Though he did set up the Satyagraha Ashram, Gandhi was also aware that he would hardly be able to devote himself entirely to it, given the demands of his political mission. It is likely that for Gandhi the Santiniketan ashram, remained a space which embodied a dream of decolonization through a way of life that combined deep spirituality with the pursuit of an aesthetic education. His early memory of the ashram was not an insignificant one. In the groves and glades of Santiniketan, in its efforts of rural reconstruction, in its art and craft endeavours, Gandhi found a haven of freedom, into which he hoped the country would awake. Could one speculate that Gandhi’s support for the institution was also a vicarious living out of an unuttered promise made to himself? To be haunted by Santiniketan was to be haunted by nostalgia for a past that was not walled up by ideas that constructed the Nation.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Works Cited

- Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi. (ed) The Mahatma and the Poet: Letters and Debates between Gandhi and Tagore 1915-1941 ( New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1997)

- Elmhirst, Leonard K. Poet and Plowman ( Kolkata: Visva-Bharati 2008) [ First Published Sept 1975]

- Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand. Asharam Observances in Action, tr. Valji Govindji Desai (Ahmedabad: Navjivan Publishing House, 1955)

- Pal, Prasanta. Robijiboni [The Life of Rabindrananth] Vol.VII ( Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, 1997)

- Tagore, Rabindranath, ‘My School’, in Sisir Kumar Das (ed) The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore Vol.II ( New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1996)

- Tagore, Rabindrananth, ‘Nationalism in the West’ in Sisir Kumar Das ( ed) The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore Vol.II ( New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1996)

- Tendulkar, D.G. Mahatma: Life of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi ( New Delhi: Publications Division, 1930)

- Thakur Rabindranath, Chithipatra, dwitiyo khando [Collected Letters, Vol. II] First Published 1942 ( Kolkata: Visva-Bharati, 2011)

- Visva-Bharati News Vol.X.No. XII June 1942

- Visva-Bharati News Vol.IX No.8 February 1946

- VBP [Visva-Bharati Papers] Rabindra –Bhavana Archives, Visva-Bharati

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I would like to thank The New India Foundation for giving me a fellowship to work on the history of Visva-Bharati and especially Prof. Ramachandra Guha for his encouragement. This essay emerged from that work. I also wish to thank Prof. Tapati Mukherji, Director, Rabindra Bhavana and the staff of the Rabindra- Bhavana archives for giving permission to access the Visva-Bharati Papers.

Notes/references: Notes/references:

| 1. |

At Santiniketan Gandhi met some of his future colleagues--Kaka Kalelkar and Chintamani Shastri, who taught Sanskrit here... For a change he introduced self-help and convinced the inmates of the necessity of cooking their food themselves. His stay was cut short by the news from Poona of Gopal Krishna Gokhales’death. (Tendulkar 160)

|

| 2. |

The other scholars invited between 1921-1925 include Morris Winternitz, Bogdanov, Sten Konow, Carlo Formichi and Giuseppe Tucci. Tagore invited the British agricultural scientist Leonard Elmhirst to help him give shape to his centre for rural reconstruction in the village of Surul, later renamed Sriniketan.

|

| 3. |

| a) |

Endowment for the stabilization of the VB |

Rs 4,00,000 |

| b) |

Capital Expenditure for Deenabandhu Memorial Cottage Hospital |

Rs 29,000; |

| c) |

Capital expenditure for sinking Deenabandhu Wells |

Rs 6,000 ; |

| d) |

Capital expenditure for Hall of Christian Culture |

Rs 20,000 |

| e) |

Endowment earmarked for the Hall of Christian Culture |

Rs 50,000 |

| |

Total |

Rs 5 lacs |

|

Swati Ganguly got her PhD from Jadavpur University. She is Associate Professor in English, Department of English and Other Modern European Languages, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan. She has worked extensively in the area of Renaissance, feminism, gender studies as well as on media issues. She also writes fiction in Bengali.

Courtesy: en.wikipedia.org

|

|