|

Kubrick as satirist

Stanley Kubrick has not been a difficult film-maker in that his films do not especially demand interpretation as, say, those of his compatriot David Lynch do. He is tricky to characterize because of his variety but if one studies his oeuvre one finds that it is dominated by satirical elements1 – with Dr Strangelove (1964) and A Clockwork Orange (1971) being full-blown satire. Satire may be described as the use of humour, irony, exaggeration and ridicule to expose social tendencies and by this token, Paths of Glory (1957) is a debunking of military conduct in the higher echelons of the army. Lolita (1962) is a satire which works through juxtaposition: conventional notions of the happy family as embodied in Charlotte Haze’s expectations of Humbert and the latter’s secret desire for her minor daughter, without guilt or regret. Paedophilia is such a taboo subject2 that the novel/film’s satirical aspect has not been widely acknowledged; it seems ‘improper’ to satirize the protocols of romance using paedophilia as a counterpoint and if a novelist or film-maker does this, it is best left unacknowledged, appears the attitude. The Shining (1980) is a horror film with its emphasis on the banality of family life. The key moments in this film are not the ghosts and the spectres but the larder of the hotel, its infinite rows of canned everything, a consumer’s dream turned into a nightmare, and Jack Torrance clicking away at his typewriter producing reams and reams of only one line – ‘All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.’ Full Metal Jacket (1987) can also be read as a satire on the American military in Vietnam since it is without the anti-war humanism of Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986) or Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1979). Kubrick’s focuses largely on the dehumanizing military preparation and suggests the murderous automatons that soldiers are made by training. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) appears a different kind of film and has been generally taken to be a mystical statement of some sort. But it is characteristically cold, almost inhuman in the way it scrutinizes technology, and it cannot be accidental that a computer is the most attractive character in it.

Kubrick’s celebrated use of music also strives for satirical effect – the rape to the accompaniment of Rossini’s ‘The Thieving Magpie’ in A Clockwork Orange, the soldiers returning after razing a village in Full Metal Jacket with the Mickey Mouse club song on the soundtrack, the destruction of the world to the strains of ‘We’ll Meet Again’ in Dr Strangelove. Kubrick’s acerbic sensibility works logically with satire and he has a view of American social life which makes it the natural butt of his mordant humour. He was never a ‘humanist’ as a film-maker and the gradual movement of Hollywood art cinema to favour a particularly benign kind of humanism – Richard Linklater (Boyhood, 2014) would be the typical example of the category – may have alienated Kubrick who spent the later part of his life in England.

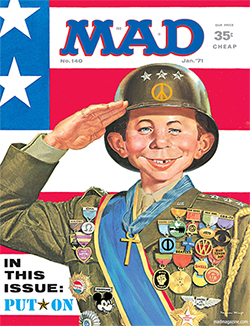

Parody and satire stand at the opposite end of the ‘feel good’ film and are now in decline. The reason is arguably that bland humanism and other kinds of ‘feel good’ sentiments generate emotions conducive to consumption, while the emotions associated with satire and mockery and some other genres do not. One might not, for instance, see oneself eating popcorn while watching The Shining. Looking outside cinema, parody and satire thrived in Mad Magazine for decades and the magazine, which poked fun at every  product from mechanical tools to entertainment3, has been in decline for the past two decades. If one examines Mad’s film parodies they induced audiences not to take blockbusters seriously and poked fun at their sentiments, and this would have naturally had detrimental effects upon film receipts. A clear relationship is often visible between sentiments promoted in popular cinema and consumption. The family values promoted by Hollywood, for instance, showcase anniversaries, holidays and gifts and this goes a long way in promoting spending. Making fun of consumption-based lifestyles might ‘cool’ the economy; satire and parody are hence implicitly discouraged, with political correctness often a pretext. Many writers of parody and satire faced law suits and this also helped destroy the sharpness of satirical films/ writing in the public space. It is perhaps for this reason that some satirical films are disguised and therefore easily misunderstood. Lynch’s Mulholand Dr (2001) which evidently satirizes Hollywood and its treatment of the auteur is taken to be much more mysterious than it is; Todd Haynes’ Safe (1995) – which satirizes a certain kind of affluent American – has been taken to be a horror film. product from mechanical tools to entertainment3, has been in decline for the past two decades. If one examines Mad’s film parodies they induced audiences not to take blockbusters seriously and poked fun at their sentiments, and this would have naturally had detrimental effects upon film receipts. A clear relationship is often visible between sentiments promoted in popular cinema and consumption. The family values promoted by Hollywood, for instance, showcase anniversaries, holidays and gifts and this goes a long way in promoting spending. Making fun of consumption-based lifestyles might ‘cool’ the economy; satire and parody are hence implicitly discouraged, with political correctness often a pretext. Many writers of parody and satire faced law suits and this also helped destroy the sharpness of satirical films/ writing in the public space. It is perhaps for this reason that some satirical films are disguised and therefore easily misunderstood. Lynch’s Mulholand Dr (2001) which evidently satirizes Hollywood and its treatment of the auteur is taken to be much more mysterious than it is; Todd Haynes’ Safe (1995) – which satirizes a certain kind of affluent American – has been taken to be a horror film.

Kubrick’s later films are always sumptuous and one does not associate satire with visual beauty and elegance. Great social satirists in cinema like Luis Bunuel, RW Fassbinder and Robert Altman made films on small budgets. Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006) is the kind of film immediately recognizable as satire. Kubrick gradually became known for his visual impeccability – as in Barry Lyndon (1975) – and one might argue that how his films looked became more important than what he was trying to say, and his acidic vision was lost amidst his painterly compositions. Kubrick was not a difficult film-maker but the satirical aspects of The Shining may have been missed4 because of Kubrick’s exacting methods. Too much effort is expended on the visual effects in the film and it may also be counterproductive for ‘cheap’ literature to be adapted for cinema gorgeously because the ‘look’ of the film indicates a level of thematic seriousness; regardless of its appeal, the look of The Shining appears to be at loggerheads with its pulp content as well as its satire.

The responses to Eyes Wide Shut

Stanley Kubrick’s last film Eyes Wide Shut (1999) which was released after his death has confused film critics around the world, who have rarely committed themselves to interpretations. Some more enterprising bloggers have however done everything from delving into esoteric aspects of the past – as into ancient secret societies – to cope with its allusions, seen commentaries on contemporary political conspiracies as well as detected Freudian subtleties. Here are some typical responses:

“The villain in Dan Brown’s book The Lost Symbol has Boaz and Jachin tattooed on his legs; and the name of the villain is Mal’akh, which is a reformed version of the name of the ancient horned deity Moloch (or Molech) as well. Alice Harford (in Eyes Wide Shut)is the female protagonist in this film, and it should be noted that her red hair is synonymous with the Scarlet Woman that Aleister Crowley identified as the goddess of his religion, Thelema. The Scarlet Woman represents the female sexual impulse and liberated woman, which Alice Harford alludes to desiring to be in her true form later in the film.” 5

“Also, small details inserted by Kubrick hint to a link between the party and the occult ritual that occurs later in the movie. When entering the party, the first thing we see is this peculiar Christmas decoration. This eight-pointed star is found throughout the house. Knowing Kubrick’s attention to detail, the inclusion of the star of Ishtar in this party is not an accident. Ishtar is the Babylonian goddess of fertility, love, war and, mostly, sexuality. Her cult involved sacred prostitution and ritual acts – two elements we clearly see later in the movie.”(6)

“In Stanley Kubrick's final film, Eyes Wide Shut, are numerous veiled allusions to the CIA's MK-ULTRA mind control experiments and Monarch sex slave programming, subjects which readers... should be well familiar. According to believed victims of Monarch abuse, their ranks number literally in thousands, and it has been alleged that these very same victims have been used extensively as sex slaves, drug mules and assassins.”7

Here is Slavoj Zizek with his Lacanian reading of the film:

“Recall Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999): it is only Nicole Kidman’s fantasy that truly is a fantasy, while Tom Cruise’s fantasy is a reflexive fake, a desperate attempt to artificially recreate/reach the fantasy, a fantasising triggered by the traumatic encounter of the Other’s fantasy, a desperate attempt to answer the enigma of the Other’s fantasy: what was the fantasized scene/encounter that so deeply marked her? What Cruise does on his adventurous night is to go on a kind of window-shopping trip for fantasies: each situation in which he finds himself can be read as a realized fantasy – firstly the fantasy of being the object of the passionate love interest of his patient’s daughter; then the fantasy of encountering a kind prostitute who doesn’t even want money from him; then the encounter with the weird Serb (?) owner of the mask rental store who is also a pimp for his juvenile daughter; finally, the big orgy in the suburban villa. This accounts for the strangely subdued, statuesque, ‘impotent’ even, character of the scene of the orgy in which his adventure finds its culmination.” 8

The film is not ‘mass entertainment’ but has nonetheless been made for a large international audience and this has us wondering; can something made for such a large audience be as esoteric as the film has been made out to be? Kubrick was widely celebrated as an auteur at the end of his career and he could have taken liberties, assumed that there was a ready audience for his films regardless of whether his intent was fully grasped or not. There is the usual sumptuousness about Kubrick’s film-making which cannot but captivate, even when his films are slight in terms of what they have to say, and one finds oneself so enveloped by a mood – as in Barry Lyndon (1975) and The Shining (1980) – that one does not ask the questions which would have been immediately asked of something less consummately mounted. Eyes Wide Shut is one of his most perfect films but if the ‘philosophical’ explanations offered for it were plausible, there would be a number of unanswered questions – which are not asked. The film has been marketed as an erotic thriller but – notwithstanding the nudity and the sex – there is a studied coldness about it which suggests that its intent is far from erotic. What follows is a reading of Eyes Wide Shut but as satirical comedy, which may not find favour with Kubrick’s fans since it suggests that the director is aiming much lower than they imagine he is.

The film

Eyes Wide Shut, which is set in New York, begins with Dr Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) and his wife Alice (Nicole Kidman) preparing to leave for a party thrown by a wealthy patient Victor Ziegler. They leave their darling little daughter Helena in the care of a babysitter on their way out. Dr Harford is evidently a successful professional but their host is much richer and Alice wonders why they keep getting invited each year to Ziegler’s party where they know no one else. Harford however discovers that he knows the pianist Nick Nightingale who dropped out of medical school when they were studying together, to pursue music. In the course of the evening an aristocratic Hungarian named Sandor Szavost dances with Alice, attempts to seduce her when she is under the influence of champagne, while her husband is similarly accosted by two young women – though he is led away by an attendant to a private room in which their host is having a crisis. A young woman with whom Ziegler was having sex has overdosed on a combination of heroine and coke. Bill Harford revives her and gets Ziegler’s gratitude.

Back in their apartment an evening later the couple discuss their respective sexual experiences, over marijuana. Alice wonders if her husband would have gone along with the two young women if he had not been interrupted, and his remonstrations that he has only eyes for Alice – because he loves her – gets him deep into trouble. We are familiar with Tom Cruise’s screen persona and Bill declines to admit even imagining himself with other women, because of his deep love for his wife. Alice is acidic and the scene concludes when she admits to having been so infatuated with a naval officer the previous summer that if only the man had wanted her, she might have given up everything. Unlike Bill’s love for Alice, hers for him does not preclude sexual fantasies about other men. It is at this point that Bill receives a call telling him of the death of a patient and he is required to proceed to the man’s house post-haste.

When Bill is led to his dead patient he finds the man’s daughter Marion alone with her father’s corpse. Her boyfriend Carl, whom she is due to marry the next year, is not present, and Marion makes use of the opportunity to kiss Bill fervently and declare her love for him (‘I love you; I love you; I love you!’). Like other, similar sequences in the film Kubrick stages it acerbically. What is to be revealed is held back while the person voicing it hesitates, seems embarrassed at the inappropriateness of the utterance before abruptly plunging ahead. In many of these sequences a woman makes sexual overtures to Bill, who is plainly ill-equipped to deal with them because of his moral baggage. I venture to add that if these sequences are wicked in their comic appeal it is not only because Bill’s prudishness is being mocked; the star’s lily-white screen persona is itself being made to look foolish. Tom Cruise plays each scene in his customary way which, given the altered context, is incongruous to say the least. But Kubrick deliberately enlists this discomfort to illuminate his protagonist’s naiveté, and there is little evidence that the star understood this aspect of his role/performance.

Bill Harford leaves Marion when Carl comes in and in the next sequence finds himself accosted by a hooker and accompanying her to her apartment. The two discuss the price and the corresponding services offered and $150 is agreed upon circuitously, with the exact services left to be decided by Domino the hooker. But Harford gets a call from Alice at this moment and Domino decides that he wants to leave. The doctor nonetheless gives Domino the promised $150, much against the girl’s protests. A walk along the pavement outside and the crossing of a few intersections leads Bill to the cafe in which Nick Nightingale is playing and this turns out to be a most fateful event. Nick Nightingale reveals that he is due to perform elsewhere that night and it emerges that there is a secret gathering of masked and costumed people and Nick Nightingale is required to play there blindfolded. These meetings have happened many times before but it is always in a different place. One time the blindfold slipped and Nick saw things he had never seen before – especially the array of women on display. All this is revealed by Nick when a call comes to give him a password, which is ‘Fidelio’ this time. Bill knows the password now and he is insistent that he wants to come along. Nick finally consents on the condition that he gets there on his own, but Bill needs to get a costume and a mask.

It is now very late but Bill Harford drives to a place which rents out costumes. The man he knew there has moved out but the shop is now owned by one Milich, who agrees to rent him a costume for the usual fee plus the $200 incentive offered by Bill. But just before the transaction is concluded Milich discovers his underage daughter half-naked with two middle-aged Japanese men in drag, hiding behind the furniture. Milich is now caught between concluding the transaction with Bill and notifying the police about the men but, when he is dealing with both issues together, his juvenile daughter nestles close to Bill, making her intentions apparent. Bill, of course, remains unmoved by this new turn and he gathers his costume and leaves – for the highpoint of the night. It is nearly 2 am and he is armed with the password ‘Fidelio’.

The gathering that Bill Harford wishes to infiltrate is being held in a mansion some distance away and he takes a cab to get there. The cab driver agrees to wait for an extra inducement of $100 and Bill is finally conducted into the exclusive masked gathering, suitably attired and disguised. What is underway in an enormous, dimly-lit space is an orgy of some sort. When Bill enters the master of ceremonies is chanting something in a strange language while Nick Nightingale plays bars of music blindfolded on an electric organ. The master of ceremonies is encircled by cloaked and masked women who soon shed their cloaks, revealing themselves to be naked except for g-strings. Bill tries to blend into the gathering but, in no time at all, finds he has been spotted as an intruder. A naked woman in a mask lets him know this first but there have also been other gazes fixed on him. Within a few minutes, he is summoned by the master of ceremonies and unceremoniously sent out, the only consolation being that he is not stripped naked because of the intervention of a masked woman, who takes responsibility for his future good behaviour.

Back home Bill Harford finds his wife fast asleep but restless and giggling. When she is woken up roughly, Alice tells him of the ‘nightmare’ she has been having but there is a hint that she is not telling him the truth about the dream but concocting an elaborate one he might be more comfortable with. Bill returns the costume to Milich but he is now cheerfully transacting with the Japanese over his daughter. The rest of the film has to do with the threats made to Bill when he tries to investigate, his visiting Nick Nightingale at his hotel but finding that he has disappeared in the company of two men, Bill visiting the hooker Domino but being informed – with the now familiar circuitousness – by an equally solicitous roommate of Domino having tested positive for HIV. Bill also learns from a newspaper that a former beauty queen was found dead from a drug overdose. He suspects that this is the girl from the previous night and this is later confirmed. Just as he is beginning to have suspicions of a monstrous conspiracy closing in on him, Victor Ziegler calls him over and explains some things to him.

“What were you trying to do last night?” Ziegler asks him. Ziegler was present at the gathering and saw what happened. He also tells Bill that he was completely out of his depth and he would understand this if he knew the names of some of the others present. “You would lose sleep over it,” Ziegler lets him know. Also, Bill’s dramatic expulsion from the party, with the girl coming to his rescue, was a charade arranged to put some fear into him. Nick Nightingale did not ‘disappear’ but was put on a plane back to Seattle. As for the girl who overdosed, she was the same hooker that Bill saved earlier. Her death was unfortunate but she was an addict and Bill knew very well that it was inevitable. Bill is left speechless by Ziegler and the film ends with his returning to Alice and Helena and telling his wife everything. The two wonder if it was all a dream but there is still a promise of conjugality for the near future.

Interpreting Eyes Wide Shut

Eyes Wide Shut is nominally quite faithful to its literary source, the 1926 novella Traumnovelle (or ‘Dream Story’) by Arthur Schnitzler, a work with psychoanalytical implications, but there are nonetheless elements in it which make its impact nasty as comedy. The key element here is the casting of Tom Cruise in the central role, and making his image the covert target of ridicule. Apart from the segments I have already described, the circuitous way in which matters are explained to him, while he waits open-mouthed, leave the star at a distinct disadvantage. In fact, if a comparison were to be made it is like Jack Torrance explaining matters in The Shining to his wife Wendy, made deliberately stupid. Kubrick also puts in more than one scene in which Bill Harford is taken to be gay and, considering that Tom Cruise has consistently played macho roles (Mission Impossible), this could be a deliberate slight on his masculinity. I am not certain that this is aesthetically legitimate but that the star is being mocked in the film has not gone unnoticed by other critics. Here is how the Slant Magazine review of the film begins: “Misunderstood as a psychosexual thriller, Stanley Kubrick’s final film is actually more of an acidic comedy about how Tom Cruise fails to get laid.” (9) Nicole Kidman, on the other hand, is hardly the butt of humour; a reason may be that the film is a take on American society and Kidman is an outsider (Australian). Moreover her persona is much more ambivalent (To Die For, 1995) than Cruise’s.

But if making Tom Cruise’s image the target of humour is the focus of the film, a question is how such a film can pass for ‘art’; is it not reasonable to expect ‘art’ to have something of larger interest for us? The only way the project can make sense as art is to regard it in terms of what Tom Cruise represents. If one studies his oeuvre, one finds that the star has, generally speaking, been an emblem of middle class aspiration. Many of his biggest hits have focussed on young people of integrity aspiring to top their professions/ vocations like Top Gun (1986), about an air-force pilot, Cocktail (1988), about a business student working part time as a bartender, A Few Good Men (1992) and The Firm (1993), which are both set among lawyers and Jerry Maguire (1996), about an honest sports manager. In Eyes Wide Shut he plays a successful doctor with many of the same characteristics. There are, in fact, several occasions on which he flashes his medical registration card at other people as if to reassure himself that his motives are strictly legitimate. To make his happiness complete, Bill’s little daughter is as adorable as Hollywood ever made children. Bill also has plenty of money; his affluence and ease with money are things that the film is always emphasizing. Yet, his exclusion from another realm is more important and the first inkling we get of this is when Alice asks him why Ziegler invites them to his parties every year although Ziegler’s circle is hardly their own. Bill’s answer is particularly instructive, “That is what you get for making house calls,” he says and it is not with any special irony. Later in the film Bill tries to break into the orgy but he is immediately spotted, despite his disguise. There is no way in which even an affluent professional like Bill could belong in the elite and his expulsion is token of this fact. Kubrick conveys something about the elite here which is also deeply mordant. The only legitimate participants at the orgy apart from the elite guests are apparently hookers. One could also argue that Bill’s sexual squeamishness is being presented as an ideal of his class and it is this squeamishness that grates on Alice – when she is prepared to admit her own fantasies. Also, Bill is initially not receptive to Marion because of his ‘integrity’ but, later, when he has been denied sexual gratification constantly he tries to call her and her fiancé picks up the phone and he cuts it off. When Bill is finally cast out of the orgy the master of ceremonies demands that he strip naked but he is saved by the woman’s intervention. The observation is that a macho star being made to strip naked in this fashion is designed as a deliberate humiliation; since Tom Cruise’s role as Bill fits perfectly with his image, the object implicitly at the centre of the humiliation is the star image as social ideal.

The film deals with several subjects which might be taboo in mainstream cinema – matters like child-prostitution (done in what might be considered an unforgivably flippant way). The use of a Serbian Milich as the child’s genial father instead of an American is to make it more tolerable; the clients are also not American but Japanese. This act of ‘political incorrectness’ may be placed alongside Bill being called a ‘faggot’ roughly and without provocation by youth on a street. Another scene unthinkable to Hollywood is a wife making deep admissions to her husband (whom she loves) but the admissions being concocted. I already described the scene where she is giggling in her sleep; when she relates the dream to her husband he is turned away from her and she is half smiling in a strange way, which is inconsistent with the admission of the ‘horrible dream’.

Coming to what the ‘elite’ means in Eyes Wide Shut, one could interpret it as the American plutocracy. It is common knowledge that there are powerful elites on behalf of which public decisions (including those pertaining to war) are taken; the way in which participants in the financial scandal of 2008 were let off and/or got key posts later only underscored this. But while the existence of this plutocracy is inferred, it still remains an elusive notion because how it operates can only be a matter of conjecture. The orgy in Eyes Wide Shut can hence be understood as representing a middle-class fantasy about the lives of this class – an elite one does not know much about. It is not a personal fantasy of Bill Harford (as Zizek has it), but a fantasy that his entire class may be living in their secret moments. Kubrick uses a Romanian liturgy, even playing it backwards, for the music in the scene to be especially weird and unlikely.

Conclusion

Kubrick’s film can be interpreted fruitfully as a satirical comedy about an affluent middle-class professional trying unsuccessfully to enter the elite, which has none of the moral niceties that he himself – as a middle-class American – has. A statement attributed to Scott Fitzgerald is the following one: “The rich are not like you and me; they are different.” Bill Harford is perhaps the kind of naive middle-class American who does not know that the rich are ‘different. ‘Eyes wide shut’ characterizes his condition but as with many of Kubrick’s other films the satire in this film is hardly apparent. Apart from its visual lushness which makes it too sumptuous for satire, there are also deliberate attempts at confusing the audience. Alice, who is so supremely bitchy/ mischievous with Bill earlier in the film, is shown without make-up and deeply disturbed at the end; this is not consistent with the film being satire. At the same time the scene does not add up to anything else either. My understanding of the inconsistencies is that Kubrick, in making the film for a wide American audience, had no conviction that its satire would be understood – simply because what was being satirized was not acknowledged. The film is a nasty attack on the morally solemn American middle-classes, the solemnity of which has been induced by constant myth-making (about the ‘American way of life’), which the plutocracy that controls America could even be sniggering at. Eyes Wide Shut is perhaps riding on Kubrick’s supreme craftsmanship and his reputation as an auteur, without the director even being particular that his (middle-class) audiences should respond to its vision of America. Perhaps if they knew what he was implying he might not be appreciated as much. One cannot but feel ambivalent about a work of great artistic beauty if it shows no faith in being able to touch an audience as it might want to.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

MK Raghavendra is the Editor of Phalanx

Notes/references: Notes/references:

| 1. |

|

| 2. |

Nabokov understood it when he says in an interview that what was demanded of him was a tersely realistic novel “I was crazy, she was crazy, I guess we are all crazy.” Vladimir Nabokov, Strong Opinions, New York: Vintage, 1973.

|

| 3. |

Here is an observation about Mad: For the smarter kids of two generations, Mad was a revelation: it was the first to tell us that the toys we were being sold were garbage, our teachers were phonies, our leaders were fools, our religious counselors were hypocrites, and even our parents were lying to us about damn near everything. An entire generation had William Gaines for a godfather: this same generation later went on to give us the sexual revolution, the environmental movement, the peace movement, greater freedom in artistic expression, and a host of other goodies. Coincidence? You be the judge. Brian Siano, "Tales from the crypt – comic books and censorship – The Skeptical Eye". The Humanist, April 1994.

|

| 4. |

Stephen King hated the film mainly for Wendy Torrance (Shelley Duval) being made such an irritatingly stupid woman and called the film misogynistic. The criticism is valid if the film is taken as a straightforward adaptation of King’s novel. Shelley Duval played live Oyl in Altman’s Popeye (1980) and one detects deliberation in choosing her to play the role, to make Jack Torrance’s rage primarily directed against wifely stupidity. The charge of misogyny will however stick, as it will with some other Kubrick films. Kristy Puchko, ‘Stephen King Just Went Off about How Much He Hates The Shining Again,’ Cinemablend, http://www.cinemablend.com/new/Stephen-King-Just-Went-Off-About-How-Much-He-Hates-Shining-Again-68032.html Accessed 9th October 2015.

|

| 5. |

|

| 6. |

|

| 7. |

|

| 8. |

|

| 9. |

|

Courtesy: staticmass.net

Courtesy: www.madmagazine.com

|

|