|

|

|

|

Some questions about microfinance and self-help groups

The editorial examines how self-help groups and microfinance may not be what they were once intended to be – the silver bullet to eliminate poverty – and this could soon become a case of the cure being worse than the disease.

Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Responses to the Editorial in Phalanx 4

Why Does the Anglophone Indian want to be a Novelist?

Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

Films: |

|

|

Avatar

by James Cameron

Read Read |

|

|

3 Idiots

by Rajkumar Hirani Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Home > Contents > Essay: R.K. Ranjan and Romit Chowdhury |

|

|

Genre and Moral Panic

Revisiting Sach Ka Saamna

R.K. Ranjan and Romit Chowdhury

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I

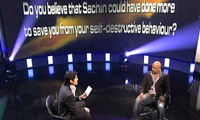

On 15th July 2009, Star Plus introduced a new show – Sach Ka Saamna – to be telecast every weekday between 10.30pm and 11pm. The channel claimed that this show would be a window to the private lives of common people and celebrities alike, who would reveal the intimate details of their lives to the public, in front of their near ones. The programme was constructed as a psychological game show rewarding contestants for “speaking the truth” about their personal lives. The authenticity of answers was to be decided by a previously conducted polygraph test. On its appearance Sach Ka Saamna created a public furore about issues of obscenity and the effect that it would have on ‘Indian moral values’. Now that the dust has settled on the panic alarms that were sounded about ‘Indian culture’ in connection to the show, it is important to revisit the controversy to uncover precisely what about Sach Ka Saamna was so anxiety inducing for the self-appointed patrols of Indian tradition. On 15th July 2009, Star Plus introduced a new show – Sach Ka Saamna – to be telecast every weekday between 10.30pm and 11pm. The channel claimed that this show would be a window to the private lives of common people and celebrities alike, who would reveal the intimate details of their lives to the public, in front of their near ones. The programme was constructed as a psychological game show rewarding contestants for “speaking the truth” about their personal lives. The authenticity of answers was to be decided by a previously conducted polygraph test. On its appearance Sach Ka Saamna created a public furore about issues of obscenity and the effect that it would have on ‘Indian moral values’. Now that the dust has settled on the panic alarms that were sounded about ‘Indian culture’ in connection to the show, it is important to revisit the controversy to uncover precisely what about Sach Ka Saamna was so anxiety inducing for the self-appointed patrols of Indian tradition.

The objective of this piece is three-fold. We examine how industrial productions interact with audience reception to create ‘genres’, the historical conditions which make possible the production of a certain genre at a specific point in time. We argue that it is the distinctive format of Sach Ka Saamna that makes it susceptible to the ‘moral panic’ that it engendered. We further demonstrate that the controversies around the show stem from the government’s efforts to simultaneously create an atmosphere suitable for its neo-liberal economic policies to find fullest fruition, and maintain ‘national’ social and cultural values. Our study emerges out of in-depth analyses of 4 episodes. However, our arguments are equally applicable to the show in general since its episodes employ the same generic features that we have scrutinised here. Through these we shall try to arrest the tendency to treat media texts in isolation from others and underscore the importance of understanding the social production of texts and meanings.

II

It is relevant that we elaborate upon the details of the show’s format before launching into our analysis. The contestants on the show face 21 questions about their lives, the answers to which have to be given either in ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The validity of the answers is tested by a polygraph test based on 50 questions already answered by the contestants, prior to the particular episode. Out of these, 21 questions are selected for the show to be telecast; the answers for these are known to no one but the contestant. There are 6 levels in the show, with the number of questions reducing with each level. Monetary reward progresses with each level, from 1lakh, 5l, 10l, 25l, 50l, to 1crore. Contestants can leave the show before a question is asked. Family, relatives and friends present at the show have a buzzer which they can sound only once to stop the contestant from answering a question. A substitute question is then asked. With every stage, questions get more personal. The show claims to “bring about a positive change by helping contestants to resolve issues of their past and to lead a better life. But above all the show rewards honesty.”

III

Considering that Sach Ka Saamna borrows its form from Moment of Truth which is an international programme, it is important to consider the present historical conditions which make such an adaptation, its legalities, possible. In the last 15-17 years, the structural adjustment programme has established consumption as the driving force behind the economy. This has established advertising as the key source of revenue for satellite television. The widening of the Indian middle-class as a social category with buying power has created a space for transnational collaborations on projects which are thought to have a considerable audience in the country. It is in this context that we may view the adaptation of the format of Moment of Truth to an indigenous production like Sach Ka Saamna. Given the difficulties of international corporations setting up satellite networks in foreign countries, frequently strategies such as selling copyright of successful programmes are adopted to maximise profit. Sach Ka Saamna’s appearance at this specific circumstance in history may be seen as an instance of globalization’s invention of indigenous narratives.

It is to be noted that by historical circumstances, we mean not simply economic processes but also that generic conventions embody the crucial ideological concerns of the time in which they are produced. In this context we may revisit the controversies that Sach Ka Saamna generated to excavate cultural meanings embedded in the text and the ways in which these meanings were negotiated by different viewing publics. As Stephen Neale stresses, the generation of meanings and their receptions are interlocked in reciprocal relationships. It will be remembered that the Minister for Information and Broadcasting, Ambika Soni, had called an urgent meeting of the National Broadcasting Association to discuss the issue raised by Samajwadi Member of Parliament Kamal Akhtar about Sach Ka Saamna, particularly the “obscene questions asked by the anchor of the programme”. The government in power was not the only ones protesting. Bhartiya Janata Party leader Sushma Swaraj also thought it was an outrageous “serial” and should be banned. "This kind of programme outrages the modesty of the women," CPI(M) leader Brinda Karat said. A PIL was filed in the Delhi High Court seeking a complete ban on the show. The High Court’s judgment rejected the appeal, saying that those who felt uncomfortable watching the show could always turn their televisions off. A close content analysis of the show throws up interesting ideological implications. It is to be noted that by historical circumstances, we mean not simply economic processes but also that generic conventions embody the crucial ideological concerns of the time in which they are produced. In this context we may revisit the controversies that Sach Ka Saamna generated to excavate cultural meanings embedded in the text and the ways in which these meanings were negotiated by different viewing publics. As Stephen Neale stresses, the generation of meanings and their receptions are interlocked in reciprocal relationships. It will be remembered that the Minister for Information and Broadcasting, Ambika Soni, had called an urgent meeting of the National Broadcasting Association to discuss the issue raised by Samajwadi Member of Parliament Kamal Akhtar about Sach Ka Saamna, particularly the “obscene questions asked by the anchor of the programme”. The government in power was not the only ones protesting. Bhartiya Janata Party leader Sushma Swaraj also thought it was an outrageous “serial” and should be banned. "This kind of programme outrages the modesty of the women," CPI(M) leader Brinda Karat said. A PIL was filed in the Delhi High Court seeking a complete ban on the show. The High Court’s judgment rejected the appeal, saying that those who felt uncomfortable watching the show could always turn their televisions off. A close content analysis of the show throws up interesting ideological implications.

The last episode (48th) of the show featured noted Bengali television actress Roopa Ganguly, whose national fame rests on her acclaimed performance in the role of Draupadi in B.R Chopra’s production of Mahabharata. Ganguly was asked questions such as: was her family life more important to her than her career pursuits, has she had an extra-marital affair; does she still love her ex-husband; does she use her age to boss over her younger boyfriend; does she really love her boyfriend; and whether she thought herself to be a responsible daughter? Interestingly, Ganguly’s replies to all these questions were in the affirmative. The furore that Sach Ka Saamna created, as we have seen, was in part due to the perceived ‘un-Indianess’ of issues discussed in the programme. But part of the protest, as exemplified by Brinda Karat’s stand on the issue, was a recreation of that strand of the women’s movement that saw the depiction of anything sexual as derogatory to womanhood. If we may anticipate our argument at this point, we would suggest that both the ideologies of the text and the notions which drove the protests stem from similar anxieties about the preservation of national culture under a perceived threat from the processes of globalization.

Ganguly’s affirmation of family being more important to her than her career again prescribes the realm of the domestic to the woman. The ‘modern Indian woman’ must thus negotiate her career in such a way that it is always second to her ‘real’ role which is that of a homemaker. Not just herself, but her entire family’s firm avowal of her always having been a ‘responsible daughter’ plays into the creation of an idea of modernity that makes certain options available to women only to firmly instate Her into a nationalist understanding of ‘Indian womanhood’. The whole show is cast in a format that hardly questions an insular understanding of Indian culture. Far from challenging conventions it in fact restores extra-marital affairs, homosexual experiences, younger boyfriends etc. as un-Indian, which must be tried by the test of fire and ultimately confessed to. The protests to Sach Ka Saamna arose from a similar understanding of what it means to be Indian. Thus, even as the government ‘liberalises’ and allows the entry of private channels and shows on the broadcasting arena, the inner sphere of domesticity where nationalist ideology locates its own subjectivity is zealously guarded from ‘global’ influences. The alarms which were raised when ‘personal’ matters were made the subject of a nationally telecast show, are emblematic of the anxiety that if this inner space enters the public, it will be susceptible to the corrupting influences of globality. The specific format of the show needs close scrutiny to understand why this show and not others on air generated the same intensity of concern that it did. Ganguly’s affirmation of family being more important to her than her career again prescribes the realm of the domestic to the woman. The ‘modern Indian woman’ must thus negotiate her career in such a way that it is always second to her ‘real’ role which is that of a homemaker. Not just herself, but her entire family’s firm avowal of her always having been a ‘responsible daughter’ plays into the creation of an idea of modernity that makes certain options available to women only to firmly instate Her into a nationalist understanding of ‘Indian womanhood’. The whole show is cast in a format that hardly questions an insular understanding of Indian culture. Far from challenging conventions it in fact restores extra-marital affairs, homosexual experiences, younger boyfriends etc. as un-Indian, which must be tried by the test of fire and ultimately confessed to. The protests to Sach Ka Saamna arose from a similar understanding of what it means to be Indian. Thus, even as the government ‘liberalises’ and allows the entry of private channels and shows on the broadcasting arena, the inner sphere of domesticity where nationalist ideology locates its own subjectivity is zealously guarded from ‘global’ influences. The alarms which were raised when ‘personal’ matters were made the subject of a nationally telecast show, are emblematic of the anxiety that if this inner space enters the public, it will be susceptible to the corrupting influences of globality. The specific format of the show needs close scrutiny to understand why this show and not others on air generated the same intensity of concern that it did.

IV

Precisely what genre does Sach Ka Saamna fall into? The difficulty of answering such a question gestures towards the fuzzy nature of genre categories. The modes, forms and contents which define a genre are based on the recognition of certain family resemblances amongst television programmes. The problems of identifying one programme as falling squarely within certain generic parameters are that the breadth/narrowness of labels is seldom satisfactory. Also, the biologism inherent is such definitions tend to essentialise genres as evolving through a standardized life cycle. Keeping these constraints in mind, it is possible to view Sach Ka Saamna as straddling different genres and programme formats. For instance, although the makers of the programme cast the show as a psychological game show, the genre ascriptions that audiences make to the programme may not necessarily be the same one. Viewers’ perception of a particular programme is reliant on their own identification of continuities and ruptures with related television formats. Sach Ka Saamna is ostensibly a game show but what it successfully does is that it takes elements from two other recognizable television formats – the soap opera and the personal talk show.

Steve Neale argues that pleasure is derived from both 'repetition and difference'. Literary theorists René Wellek and Austin Warren also observe that 'the totally familiar and repetitive pattern is boring; the totally novel form will be unintelligible – is indeed unthinkable'. Sach Ka Saamna’s pleasure principle rests on precisely this logic. The generic features of a game show format, (such as questions which get more difficult with each level, increasing rewards for higher levels, help-lines etc), are easily identifiable in Sach Ka Saamna. The set, music which builds suspense between answers, special chair for the host and contestants, placed at the centre, revelation of answers on an expanded screen, are all usual elements of game shows. But what this show does is that it takes these conventions and adds elements from personal talk shows and the Indian soap opera to create a distinct format of its own. Thus, audiences derive pleasure from both recognising familiar elements and also remain hooked by the novelties which it offers. For instance, in place of questions of general awareness, we have questions related to contestants’ personal lives. The buzzer of the quiz/antakshari show, is used here by family and friends to stop the contestant from answering a particularly difficult question without being eliminated, a sort of helpline. Furthermore, the flashback video element in talk shows is introduced as a novel way of questioning the contestant by a close friend/family member. Roopa Ganguly’s boyfriend asks her through video conference, if she regretted rejecting his marriage proposal. Steve Neale argues that pleasure is derived from both 'repetition and difference'. Literary theorists René Wellek and Austin Warren also observe that 'the totally familiar and repetitive pattern is boring; the totally novel form will be unintelligible – is indeed unthinkable'. Sach Ka Saamna’s pleasure principle rests on precisely this logic. The generic features of a game show format, (such as questions which get more difficult with each level, increasing rewards for higher levels, help-lines etc), are easily identifiable in Sach Ka Saamna. The set, music which builds suspense between answers, special chair for the host and contestants, placed at the centre, revelation of answers on an expanded screen, are all usual elements of game shows. But what this show does is that it takes these conventions and adds elements from personal talk shows and the Indian soap opera to create a distinct format of its own. Thus, audiences derive pleasure from both recognising familiar elements and also remain hooked by the novelties which it offers. For instance, in place of questions of general awareness, we have questions related to contestants’ personal lives. The buzzer of the quiz/antakshari show, is used here by family and friends to stop the contestant from answering a particularly difficult question without being eliminated, a sort of helpline. Furthermore, the flashback video element in talk shows is introduced as a novel way of questioning the contestant by a close friend/family member. Roopa Ganguly’s boyfriend asks her through video conference, if she regretted rejecting his marriage proposal.

Attention must also be drawn to the way in which the show has been edited. At crucial junctures in the game, when a particularly personal question has been asked, the camera cuts away to focus on family members present on the show, to register their responses. We would argue that the peculiar nature of the show in question could not possibly succeed if the audience were not invited to personally relate to the contestant’s family and near ones through clever editing techniques. These are not general knowledge questions. The answers given on the show have the potential to alter personal ties. The editing augments these possibilities. It is also noteworthy that Sach Ka Saamna replaced Kyun Ki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi on the same channel. The editing techniques that we mentioned may also be read as a recreation of the intrigues in which soap operas abound. It would be familiar to the audience that in family soaps, when something momentous is about to be revealed, the camera frequently cuts away to those present on the scene to register their reactions. It is in these ways that Sach Ka Saamna takes familiar elements from various formats and revises them to suit its own distinct end. Viewing pleasures can be derived from sharing our experience of a genre with others within an 'interpretive community' which is characterized by its familiarity with known genres. For instance, the show which features the transgendered person Laxmi sees her being asked if she ever tried to commit suicide. The moment this question is raised the camera cuts away to her father who later reveals that he had never known that Laxmi had indeed tried to kill herself. Of-course when this happens, the accompanying music builds up a cinematic sense of intrigue and suspense.

Genres can thus be seen as mediating between industry and audience. On the one hand they ensure effective communication by relying on previously built relationships between the two. On the other, genres invite an active participation process on the part of the viewer by encouraging them to read and relish new elements in formats.

V

The truth quotient is a powerful element in Sach Ka Saamna. In this section we lay open what forms of knowledge the show makes available to the audience. As Fiske and Hartley have argued in Reading Television, television is primarily an oral medium; but given our culture’s exaltation of literate modes of expression, television also incorporates literate elements into the medium. Literate modes of thought engender realist expressions and realism as a form is a characteristically bourgeois genre. Sach Ka Saamna fits into this schema by introducing strong realist elements in its narrative. It is here that the omnipresent polygraph test plays a crucial part. The truth quotient is a powerful element in Sach Ka Saamna. In this section we lay open what forms of knowledge the show makes available to the audience. As Fiske and Hartley have argued in Reading Television, television is primarily an oral medium; but given our culture’s exaltation of literate modes of expression, television also incorporates literate elements into the medium. Literate modes of thought engender realist expressions and realism as a form is a characteristically bourgeois genre. Sach Ka Saamna fits into this schema by introducing strong realist elements in its narrative. It is here that the omnipresent polygraph test plays a crucial part.

Every show begins with a review of the polygraph test, its scientific veracity and modes of administering, which authenticates every response of contestants. As audiences and contestants wait for its verdict, suspense is generated as a narrative ploy. In Vinod Kambli’s episode, we see repetitive close-ups of him clutching onto a cross for support. In this way, the polygraph test establishes realism not as one way of seeing but as the only approach to reality. Realism extends the ideology of the bourgeoisie by erasing its own tools of constructing reality. In doing so it claims to provide unmediated access to a reality out there, and removes the possibility of recognising alternative versions of reality. In Sach Ka Saamna, the flaws of the polygraph test are not discussed. We are never told that changes in physiology may be for reasons other than lying and that the polygraph has no way of reading these variations. The advertisements shown also make oblique contributions to this idea of a single truth. Sprite asks us to believe in Seedhi Baat No Bakwas, and a pressure cooker company cautions about what is at stake if the polygraph test reveals a lie – ‘Prestige’. In a Marxist sense, genre can thus be seen as replicating the social control of the dominant ideology. But what scope does this leave for the question of agency?

Roopa Ganguly gets eliminated when her answer that she loves her boyfriend is invalidated by the God-like voice of the polygraph. But her reply in this context is very significant. She says that the notion of love holds a very different meaning for a 40-year-old woman who has seen many more shades of life than a younger person; the polygraph, she says may not be able to understand these complexities. This response locates the transgressive possibilities within bourgeoisie control. Even though the host, Rajeev Khandelwal reiterates the authenticity of the polygraph test, we as audience are able to negotiate with the notion of the existence of multiple versions of truth.

VI

Stuart Hall’s notion that each text provides a reading position for its audience/reader, a set of preferred meanings for them to decode, bears recall. It is in this way that every text constructs for it an ‘ideal viewer’. In this connection, we would argue that the ideal viewer which Sach Ka Saamna creates occupies the same ideological position as the ideal citizen of a neo-liberalised economy. As Meenakshi Mukherjee demonstrates in her influential essay ‘The Anxiety of Indianness’, the creation of a national identity is simultaneously about eliding all differences within the territory and marking its difference from the other. The show’s claim to help contestants resolve personal conflicts is geared towards the recreation of the heterosexual, middle-class home, and the establishing of work as virtue, itself making possible the most pleasurable leisure – the necessary staples for any patriarchal, capitalist society. The show and the immanent panic about Indian culture lay open contemporary anxieties about the question of national culture; but these concerns are ultimately resolved according to the ideological project which makes such a show possible. Rajeev Khandelwal’s reiteration of Satyamev Jayte, evokes nationalist attempts to foster an atmosphere suitable for neo-liberal economic policies to find fullest fruition and simultaneously maintain ‘national’ social and cultural values. Stuart Hall’s notion that each text provides a reading position for its audience/reader, a set of preferred meanings for them to decode, bears recall. It is in this way that every text constructs for it an ‘ideal viewer’. In this connection, we would argue that the ideal viewer which Sach Ka Saamna creates occupies the same ideological position as the ideal citizen of a neo-liberalised economy. As Meenakshi Mukherjee demonstrates in her influential essay ‘The Anxiety of Indianness’, the creation of a national identity is simultaneously about eliding all differences within the territory and marking its difference from the other. The show’s claim to help contestants resolve personal conflicts is geared towards the recreation of the heterosexual, middle-class home, and the establishing of work as virtue, itself making possible the most pleasurable leisure – the necessary staples for any patriarchal, capitalist society. The show and the immanent panic about Indian culture lay open contemporary anxieties about the question of national culture; but these concerns are ultimately resolved according to the ideological project which makes such a show possible. Rajeev Khandelwal’s reiteration of Satyamev Jayte, evokes nationalist attempts to foster an atmosphere suitable for neo-liberal economic policies to find fullest fruition and simultaneously maintain ‘national’ social and cultural values.

But then we have Laxmi Narayan Tripathi. When asked by the host if her family has been able to accept her completely as a woman, she laughs and tells him: ‘why should they; I am not a woman’. In the final count, we cannot talk about dominant ideologies of the text without noting the many ways in which they are read against the grain by the audience and contestants alike as discursive subjects.

Notes/ references

| 1. |

|

| 2. |

Fiske, John: Television Culture. |

| 3. |

Neale, Stephen: Genre. |

| 4. |

Quoted in The Hindu |

| 5. |

Chandler, Daniel: Genre Analysis. |

| 6. |

However it is important to remember that “an individual text within a genre rarely if ever has all the characteristic features of the genre.” Fowler, Alastair: Genre. |

| 7. |

Stam, Robert: Film Theory |

| 8. |

Feuer, Jane: Genre Study and Television. |

R.K. Ranjan and Romit Chowdhury are graduate students of Media and Cultural Studies at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

This essay should perhaps be read alongside the previous one, which looks at another reality show, one that seeks to define the perfect bride, while allowing for consumer responses such as the elimination of candidates. It is evident that reality television provides fertile ground for researchers to enquire not only into how the space between the traditional and the global is being negotiated but also into how ‘consumer response’ is accommodated as a factor. This last aspect, in a sense, makes reality television a huge ‘advance’ on cinema.

Editor

|

|

|

|

|

|

Top |

|

|

|

|

|