|

Background

Tracing the development of form and narration in a national cinema has generally not been an onerous task. Whether from Hollywood, France or India, cinema follows the earliest precedents in many ways. Individual motivation, for instance, drove the action in DW Griffith’s films as it still does in American cinema. The exceptions may be the cinemas of countries which have gone through political upheaval or turmoil – like Germany and Russia. The dominant film form is not accidentally adopted but is historically and politically engendered and the cinemas of Germany and Russia, understandably, bear little resemblance to their respective cinemas of the 1920s. If associating the changes in film form with political transformation is a complicated task, Russian cinema, being formally more distinguished, offers a much greater challenge today. Soviet cinema attained renown through its use of montage in the 1920s but Russian cinema is not only difficult to pigeonhole but is also marked by a variety which defeats characterization. Still, ‘variety’ itself could be its defining feature after 2000 and may have arisen for political reasons. While providing a large amount of information cannot be avoided, the following is, essentially, an attempt at interpreting politically the trajectory of Soviet/ Russian cinema from the 1920s to the new millennium. The conjecture is that while politics may not entirely determine film form, it nonetheless influences its direction in time.

The artistic roots of Russian cinema

The first thing that draws one’s attention in accounts of the reception accorded to cinema in Russia in the early part of the twentieth century is the amount of intellectual debate generated around it. The accounts have us believe that even in the 1900s writers like Maxim Gorky, Alexei Tolstoy and a host of major artists, intellectuals and literary theorists and critics had become

|

involved in understanding of cinema’s essential nature and the way it transformed man’s understanding of himself and the world (1). Unlike in America where cinema began as an essentially lowbrow exercise, the desire in Russian cinema to compete with ‘high art’ was present from the very beginning. The story of how the first Russian feature film, Alexander Drankov’s film of Pushkin’s Boris Godunov (1907) was made is indicative of this. Pushkin’s play had always been regarded as difficult to stage and Stanislavski had suggested breaking up the action into a series of fragmented excerpts and this was the model followed by the Moscow Art Theatre, which was staging the play in 1907. The resemblance of this production to cinema was duly commented upon by the audience and, to cut a long story short, the idea of filming the performance caught Drankov who, believing that the Moscow Art |

Theatre production was being filmed by someone else, decided to film an open air production of the play by another company (2). This bias towards the classics as subject matter for cinema accounted for ‘Russian endings’ – tragic fates emulating those in classical tragedy rather than the happy endings common to Western film melodramas (3), which were demonstrably lighter in literary content.

A characteristic of the Russian cinema of the 1910s was the immobility of the characters but rather than signifying directorial deficiencies, the static mise-en-scène, in actual fact, was the result of a conscious aesthetic program. A theorist of the period divided the schools of cinematography into three kinds: a) that based on movement as in the American school, b) the one based on forms as in the European school and c) the psychological Russian school (4). Later, in 1916, the champions of Russian style began to call American and French cinema ‘film drama’, a genre that in their view was superficial. ‘Film drama’ was contrasted with ‘film story’, the preferred genre of Russian cinema. The film story, it was said, breaks decisively with all the established views on the essence of the cinematographic picture because it repudiates movement. The resulting ‘aesthetics of immobility’ could be traced back to two sources: the psychological pauses of the Moscow Art Theatre and the acting style of Danish and Italian cinema. When they came together in Russian cinema, these sources formed a new synthesis: the operatic posturing of the Italian diva acquired psychological motivation, while the acoustic and intonational pauses of the Moscow Art Theatre found its plastic equivalent on the screen. That gave rise to the minimalist technique of the Russian film actor, which was put to use by the style of film direction which developed (5), in contrast to which American acting was too ‘fidgety’.

Another feature of silent Russian cinema before the Revolution was the importance given to the inter-title. Rather than merely directing the action, the inter-title in silent cinema was seen as literary. A short story was preferred as the source of a screen adaptation than a play made from the same story. Equality was proposed between the inter-title and the images like that in an illustrated book. Also popular before 1917 was the recitation with a lecturer rather as commentator with suitable academic paraphernalia to make it look intellectual. Lev Tolstoy himself was excited by the idea of cinema with such a commentary (6).

With the revolution in 1917, a possible influence upon cinema was also that of Constructivism, an artistic and architectural movement that originated in Russia beginning in 1919, which was a rejection of the idea of autonomous art. The movement was in favor of art as a practice for social purposes. Its influence was pervasive, with major impacts upon architecture, graphic and industrial design, theatre, film, dance, fashion and to some extent music. Although the Communists were beset on all sides and a ferocious civil war was being fought, the importance of cinema was understood by the Communist state; on the front were always cameramen shooting

|

the war and directors like Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein began their artistic/ film careers in the Red Army. While Soviet cinema itself was in a terrible state in 1920 not only because many of the most prominent in cinema had become émigrés in Europe but also because industry was in tatters on account of the ongoing Civil War, Soviet cinema began its process of consolidation in 1921 with the end of military hostilities and the New Economic Policy (NEP) which permitted free trade (7). One can say that during a few years beginning with 1924, Soviet was at its avant-garde best, not only with the experiments in montage – Kuleshov, Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov and Pudovkin but also in set design where the influence of the Constructivists can be seen as in Yakov Protazanov’s science fiction film Aelita (8). Still, it was montage rather than set design which earned for Soviet cinema its place in film history.

|

Montage and choreography

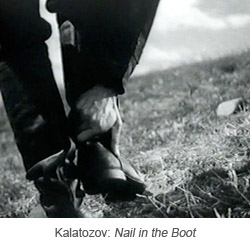

As will be familiar to students of film history, the key notion at the heart of early Soviet cinema is montage although each filmmaker-theorist - Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dziga Vertov and Kuleshov, to name the important ones – approached it differently. In contrast to Hollywood editing which simply tried to deliver the story to the audience with minimal interference through an emphasis on continuity, the Soviet school saw montage (the French term for editing) as creating meaning in a different way altogether, sometimes through rhythmic manipulation, sometimes by using it as metaphor and sometimes as an intellectual tool in the service of (usually political) ideas of a more abstract nature. The key notion underlying montage theory of the early Soviet era is that meaning does not exist in the individual shots; it only arises when they are juxtaposed, i.e. through montage which apparently had its origins partly in the rhythm of the dance (9). Since the effects that the early soviet filmmakers obtained through montage were striking, one would have expected montage theory to grow from strength to strength. As it happened, however, most of the filmmakers abandoned it without theoretical bases being provided in the 1930s. Eisenstein, the most celebrated of the filmmaker-theorists went on to make Ivan the Terrible in two parts(1944, 1958) which seems, compositionally, closer to German expressionism than to the filmmaker’s Battleship Potemkin (1925). An even better illustration is perhaps the difference between two films by Mikhail Kalatozov – Nail in the Boot (1931), which uses montage and rhythm to telling effect and his later The Cranes are Flying (1957), in which he uses mise-en-scene – the uncut tracking shot particularly.

Montage and mise-en-scene represented – to the film theorist Andre Bazin – polarities in film style, the first corresponding to dismemberment of film space in order to strengthen expressivity and the second to maintaining its integrity. While there was little aesthetic justification from Soviet filmmakers for abandoning montage, it has been noted by film historians that the end of montage as the operating principle happened under Stalin for political rather than aesthetic reasons. With censorship of films becoming much more severe, it was found that the screenplay was more easily scrutinized and this meant an insistence on the screenplay as the source of cinema rather than montage (10). But the way in which the screenplay could be subverted by the completed film was also demonstrated by Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible (Part 2), the screenplay of which had been approved (11) by the censors but which was banned when the completed film was seen by officials in 1946. After the 1920s, therefore, montage is less in evidence although some of its effects are still achieved differently.

Another important aspect of filmmaking in which Soviet cinema attained proficiency in the 1920s was choreography. Choreographed movement in Soviet cinema apparently had its origins in the work of theorists Frenchman FA Delsarte, the Swiss J Dalcroze and Delsarte ’s disciple Jean d’Udine – which had its initial influence in theatre. There was, in the 1910s and early 1920s, a

|

reaction against the methods of Stanislavsky’s Moscow Art Theatre – which later gained ground in the US – and the work of these theorists offered an alternative. Delsarte’s teaching consisted to a large extent in the accentuation of the rhythmic side of mime and gesture. Dalcroze created a system of rhythmic gymnastics which was extremely popular in the 1910s and on which he based an original aesthetic theory. Delsarte’s ideas began to penetrate Russia at the very beginning of the twentieth century and achieved real popularity around 1910 -13 when the former director of the Imperial Theatres, Prince Sergei Volkonsky, became its advocate. Volkonsky published a series of articles on Delsarte and Dalcroze in the periodical Apollon and then published, under that periodical’s imprint, several books giving a detailed exposition of the new acting system. reaction |

against the methods of Stanislavsky’s Moscow Art Theatre – which later gained ground in the US - and the work of these theorists offered an alternative. Delsarte’s reaction against the methods of Stanislavsky’s Moscow Art Theatre – which later gained ground in the US – and the work of these theorists offered an alternative. Delsarte’s teaching consisted to a large extent in the accentuation of the rhythmic side of mime and gesture. Dalcroze created a system of rhythmic gymnastics which was extremely popular in the 1910s and on which he based an original aesthetic theory. Delsarte’s ideas began to penetrate Russia at the very beginning of the twentieth century and achieved real popularity around 1910 -13 when the former director of the Imperial Theatres, Prince Sergei Volkonsky, became its advocate. Volkonsky published a series of articles on Delsarte and Dalcroze in the periodical Apollon and then published, under that periodical’s imprint, several books giving a detailed exposition of the new acting system.

The Volkonsky system compared man to a dynamo through which the ‘synaesthetic’ rhythmic inductive impulses pass. The proposition is that human emotion is expressed in external movement and movement can ‘inductively’ provoke in the spectator the same emotion that gave rise to the movement. It is maintained that for every emotion, of whatever kind, there is a corresponding body movement of some sort and it is through that movement that the complex synaesthetic transfer accompanying any work of art is accomplished. The Delsartian, ‘technological’ part of the system is essentially orientated towards the search for a precise record of gesture, its segmentation like musical notation and the exposure of the psychological content of each gesture (12). It was through theatre that these ideas penetrated film circles and the first traces of their influence can be found around 1916. By 1918 -19 among film-makers there was already an entire group of followers of Delsarte and Dalcroze. By coincidence there were among them a number of film-makers who actively supported Soviet power and, as a result, occupied key posts in cinema immediately after the October Revolution.

The desire to divide action into minute physiological elements (and the enormous role attributed to the eye in this process) led Vladimir Gardin (13) towards the widespread use of close-ups, i.e.: the cutting off of the actor by the frame of the shot, which was partly analogous to Delsarte’s ‘independence of the limbs from one another’. The implication of montage in the system may be gauged from Gardin’s experiments with the model actor taking the form of a series of exercises with ‘velvet screens’. With the aid of these screens he formed a window whose shape resembled the frame of a film shot. Into the window he put the face of the actor who had to work out precise mimic reflex reactions to externally provided stimuli. One can see in this a precursor to Lev Kuleshov’s celebrated experiments with the actor Ivan Mozzhukin. Kuleshov, it must be recollected cut the actor’s same impassive countenance to different stimuli to suggest different emotions.

There were many other theorists and practitioners – like Alexander Tairov, Vsevelod Meyerhold, Boris Fernandinov – working with actors and trying to understand the human body as a machine. While this is enormously interesting to anyone interested in the evolution of film language, it is only necessary to understand at this point that stage movements were being understood as akin to poetry and music (14) and choreography was, essentially, akin to music. Since Vsevolod Pudovkin’s theories of montage were deeply influential, it may be useful to look at the choreography in his Mother (1926) to understand what choreography meant in the 1920s. Other film-makers like Eisenstein (Battleship Potemkin, 1925), Dovzhenko (Arsenal, 1929) and Mikhail Kalatozov (Nail in the Boot, 1931) did not use montage in the same way but what is concluded about Pudovkin may be broadly applicable to their films as well (15).

|

At the beginning of Pudovkin’s Mother is a sequence in which the drunken father returns home and tries to appropriate the clock – to pawn it for more vodka. This sequence is edited in the recognizable Pudovkin way: father entering room (long shot, low angle) – close-up of belligerent father with bloodshot eyes glancing right and left – sleeping son – father looking ahead – clock hanging on the wall – mother staring tiredly back – father (long shot) striding forward – mother’s eyes following him – father detaching the iron hanging from the clock – putting it into his pocket (close-up) - father looking up at clock (long shot)... |

While movement in this sequence is caught entirely through montage the effects are obtained by combining concordant elements in the manner of orchestrated music. This is even truer of the sequence which follows – a pub scene in which the workers are ‘resting’ after work. It is important here that Pudovkin also has the means to convey movement without using montage because this means that movement and not the cut is the primary interest. In the pub scene, for instance, there are inclusive shots in which activities of different kinds are happening at the same time – a waiter serving someone, a drunkard staggering from his chair towards the counter, an orchestra in the top left hand corner, people dancing in the far distance to the right. These inclusive shots are immediately cut to tighter others in which details are singled out but the presence of the inclusive long view is unmistakable – as is Pudovkin’s orchestration of movement within a single frame. When Pudovkin shows two or more faces within a single frame, the faces either represent different character types or are composed differently – like the three men at a table watching a disturbance, each one studying it with a marginally different attitude – attention, irony and indifference.

That this is ‘composed’ like music – with harmony as the operating principle – and is not simply a ‘realistic’ depiction of an actual scene is suggested by the fact that DW Griffith – who influenced the Soviets greatly – does not have the same capabilities at his command. Birth of Nation (1915), for instance, handles its action very differently. Griffith’s film rarely has two or more faces within a single frame and groups are shot from a distance without ‘choreographing’ crowd movement. In an early segment dealing with a flock of abolitionists, the seated group is filmed from behind so that we do not catch individual faces; the only countenance - seen from a distance - is that of the man getting contributions. Pudovkin’s film also has a depth of focus that Griffith’s film lacks and it therefore incorporates more detail. If Griffith is simply showing contributions being collected, one can imagine Pudovkin doing the same scene, the congregation responding to an expectation in a less than uniform way – with enthusiasm, indifferent submission as well as resistance.

Realism and ‘polyphony’

Soviet realism and montage were contrasted unfavorably by Andre Bazin with the kind of realism in which mise-en-scène (rather than montage) is the operating principle (like the work of the Italian neo-realists) but the films of the early Soviet directors have a virtue which remains largely unmatched – their sense of movement as orchestrated music. The important thing is that choreography consists of combining individual actions which are not alike; when brought together, they suggest a whole that is not simply a collection of its constituent parts. ‘Choreography’ as thus understood involves composing ‘movement’ in a broader sense – because movement is created by juxtaposition (within the same frame or through the cut) rather than catching physical activity. A collection of faces at a table – set differently although directed towards one stimulus – would imply ‘choreography’.

The first thought about choreography in silent Soviet cinema is that it is simply a technique which can be learned but its implications also go deeper; cinema in the Stalin era appears to lose it. I compared Pudovkin’s Mother to Griffith’s Birth of a Nation and it is widely understood that Pudovkin was influenced by Griffith and tried simply to bring the story together – while Eisenstein employed deliberately ‘explosive’ editing effects to make emotional responses stronger. Still, Griffith is making us absorb the film at the plot or story level and empathize while Pudovkin is making us aware of its construction. Pudovkin’s deviation from Griffith arises because, like the Constructivists and Bertolt Brecht in later theatre, the Soviet film-makers of the 1920s tried to create an audience which would be one of active viewers. It is not enough for Pudovkin that the audience is manipulated into empathizing; he demands that it engages actively with what it sees on the screen.

If there is the attempt here to mobilize the public towards a single political agenda, ‘plane polarize’ it as it were, there is also an admission that the public is initially in an unpolarized and unreceptive state from which it needs to be critically aroused, and this is where ‘choreography’ becomes important; its application or employment conveys the sense that the world has no single meaning and that perceptions of its nature are ‘polyphonic’ – though ideological affinities and broad class interests will help subordinate the different perceptions. To draw a tentative literary parallel, Mother is like a ‘dialogic text’ in which the constitutive elements are allowed a liberty/ polyphony which although subordinated to the authoritative discourse of Marxist-Leninist doctrine (16), still reveals itself above it.

|

It will perhaps strengthen my argument if Pudovkin’s film is placed alongside Mark Donskoi’s Mother (1956), which adapts the same novel by Maxim Gorky. This is a film which came out in the thaw period after Stalin’s death but Donskoi (who came into prominence in the Stalin era) made other films (The Childhood of Maxim Gorky, 1938) which reveal the same characteristics. Donskoi’s film has an early segment comparable to that from Pudovkin’s film – the belligerent father returning to his impoverished home and clashing with his wife and son. The segments from the two films contain differences in their narrative elements – e.g. the son returns with his father from work here while |

in Pudovkin’s film the son is asleep when the father returns – but more important from the perspective chosen is the use of the ‘eyeline match’ in the two films.segment comparable to that from Pudovkin’s film – the belligerent father returning to his impoverished home and clashing with his wife and son. The segments from the two films contain differences in their narrative elements – e.g. the son returns with his father from work here while in Pudovkin’s film the son is asleep when the father returns – but more important from the perspective chosen is the use of the ‘eyeline match’ in the two films. In Pudovkin’s film the father has his eyes only on the clock and the iron which he wishes to take away and he notices his wife and son only when they try to stop him, when he pushes them aside. In Donskoi’s film there is palpable hostility between the man and his family but his acknowledgement of them comes first; it is in their respective use of the eyeline match that the attitudes of the two films are largely manifested (17). When people make eye contact conspicuously, there is an acknowledgement of each other not only as persons to negotiate with but also as viewpoints to accommodate. One can conclude that where in Pudovkin’s film the mother and her husband exist on different planes of understanding but are forced to transact because of the mother’s instinct for survival, Donskoi’s film shows man and wife, despite their underlying distrust of each other, as being together on the same plane – i.e. sharing a single understanding of their milieu. The difference between the two couples is this: the first is just two people who live on different planes of awareness (Pudovkin) while the other is mutually distrustful but with the cause of the distrust established between them (Donskoi). If the quality of ‘polyphony’ is in evidence in Pudovkin’s realism but not in Donskoi’s (18), the Stalin era is the period in which the polyphony of Soviet cinema was interrupted – until it reemerges in later cinema in the Gorbachev era.

‘Socialist Realism’ and its effects

In its early days the Soviet government was internationalist in its aims but that changed with the ascent of Stalin. Stalin had formulated his personal doctrine generally known as ‘socialism in one country’ as early as 1924 and this was apparently in response to Leon Trotsky’s ‘permanent revolution’ which argued that socialism could not survive in one country but needed to become internationalized (19). Soviet film-making, although it declined artistically under Stalin, became a vastly more important ideological exercise than had been imagined by the early theorists. Ideology is (in Marxist terms) constituted largely by unconscious predispositions owing to economic forces of which one is not fully aware. Instead of the audience reacting to cultural issues in a consciously political and critical way (20), it was encouraged to absorb political ideas subliminally so that they became part of a value or belief system. History was central but rather than history being pre-existent to the film, which only ‘adapted’ historical narrative, film became an instrument through which history was ‘constructed’. The use of cinema as a means of constructing history is not restricted to totalitarian systems but film was used in the twentieth century most effectively by Hitler (21) and Stalin. Stalinism was exceptionally sensitive to the problem of consumption and assimilation of filmic texts and the creation of ideology through the process.

|

Preoccupied with the ideological validation of its own historical legitimacy and creating a new Soviet identity which was dependent on it, Stalinism relied on cinema, seeing in this ‘most important of the arts’ the most effective form of propaganda and means of organizing the masses. Stalin therefore directly intervened in the management of Soviet cinematography and devoted attention to it (22). Alongside came the systematic denigration of the pioneers because they had experimented with film structure and narration instead of constructing history in the consciousness of the masses as a singular truth. The films of directors like Eisenstein and Vertov, were declared ‘plotless’, which in the new understanding had the same implications as ‘unideological’. “The plot of a work,” noted the then head of Soviet cinema, Boris Shumyatsky, “is the constructed expression of its ideas. The plotless form . . . is |

powerless to express any significant ideas.” (23) As a film historian phrases it:

“The inevitable and total historicism of Stalinism was linked exactly with its total ‘realism’; the ‘truth of life’ (or the ‘truth of history’) had to shine from the screen with the unfading light of the mimetic.” (24).

Socialist Realism – the official aesthetic creed under Stalin – did not simply use history. History proves to be the basis of the legitimacy of Stalinism and the adjustment of ‘historical images’ were deliberately made to fit their ‘prototypes’ from the past. The middle ages, for instance, were consistently presented as an analogy for the present. It was officially declared that the viewer went to the cinema to become acquainted with reality, and it therefore followed that historical and artistic truth were fused inextricably together (25).

One of the key genres of the Stalin epoch was the biography of a charismatic leader, whether Yemelyan Pugachev, Stenka Razin, Peter the Great, Alexander Suvorov or Pavel Nakhimov. Sergei Eistenstein’s Ivan the Terrible (Part 1) received an important state award but Eisenstein had deliberately shot it in an operatic style with exaggerated gestures, arguably to prevent its reading by the public as ‘real history’. Finances being scarce for filmmaking, it became Soviet film policy in the 1920s that commercial films needed to be made in order to fund the unviable ‘class films’ which was how the experimental work of the pioneers was described. Lenin had died in 1924 and Stalin gradually strengthened his hold on the party thereafter. After initially refusing to take sides on film aesthetics, it became the growing party view that “the main criterion for evaluating the formal and artistic qualities of films is the requirement that cinema furnishes a form that is intelligible to the millions” (26) and one can see in this the movement away from a politically critical audience envisaged in the 1920s towards the creation of ‘ideology’. With the demand for entertainment and the arrival of sound, it was natural that montage should come under attack from Boris Shumyatsky, who was the de facto executive producer for the state film monopoly from 1930 to 1937. It was at this juncture that the plot was identified as the basis of entertainment and the ‘plotless’ film castigated. Montage represented ‘creative atavism’ and plot represented ‘the discipline of the concrete tasks that our mass audience is setting’. Plot necessitated the script and an effective script had to be worked out carefully. “At the basis of every feature film lies a work of drama, a play for cinema, a script,” (27) was the point asserted.

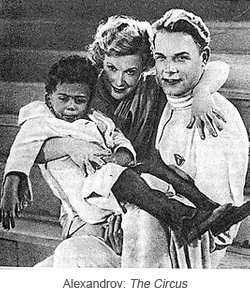

Since the classes hostile to the proletariat had been liquidated, it followed that responsible task was the creation of ‘joyous spectacle’ and genres like comedy, musicals and even fairy tales thrived. Shumyatsky later visited Hollywood and came up with a gigantic plan to set up a Soviet film city in Crimea. This became too expensive and he fell from favor with Stalin – to be executed in 1938 – but he had laid the foundation for popular entertainment in the Stalin era in which some of the most talented filmmakers collaborated (28).

|

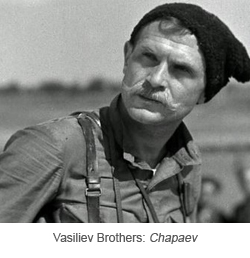

A film not only held to be the culmination of Soviet film practice but also the greatest of Soviet films was the Vassiliev brothers’ Chapaev (1934), a Civil War drama with an ‘invisible’ editing style. Seeing this alongside an earlier Civil War film Mikhail Kalatozov’s Nail in the Boot (1931), which, although intended as a propaganda film, was banned, reveals the changed aesthetics. Nail in the Boot is about the Red Army losing an armored train – because a nail protruding in a boot prevents a message asking for reinforcements from being carried to the battalion headquarters. Kalatozov’s film uses montage to great effect and is the epitome of the aesthetic likening the human body to a machine. The film is shot and edited in staccato fashion with the machinery (guns, train, bullets) not differentiated from the |

human content - soldiers, workers and members of a tribunal. The faces chosen are also hard and appear sculpted. Chapaev is about the exploits of a Red Army general who was born a poor peasant but defeated the trained generals of the Tsarist White Army. Chapaev is an action film

|

and tries to present the Red Army hero as a human being, warts and all and there are also light moments with his assistants and the political commissar Fumanov, anecdotes and jokes about whom later became folklore.

As against Kalatozov’s film which may have been shot with a handful of actors, Chapaev has a huge cast but it is Nail in the Boot which is arguably closer to an ‘epic’. Both films are about the past but it has been argued by Mikhail Bakhtin (in contrasting the epic and the novel) that the past constituting the content of the epic is unimportant. As he phrases it, the formally constitutive element of the epic as a genre is the ‘transferal of a |

represented world into the past’. Nail in the Boot is constructed to draw an elemental lesson from the past and, although it pertains to a moment in the Civil War of a decade ago, its participants stand on a different ‘time-and-value plane’ from the film-maker and the audience (29).

Chapaev, in contrast, is – like Ben-Hur (1959) or Novecento (1976) – closer to a novel and is enacted with the familiarity of a contemporary story although the past constitutes its content. One of the criteria by which Bakhtin identifies the novel is its “stylistic three-dimensionality, which is linked to the multi-languaged consciousness realized in it.” This is a characteristic Bakhtin associates with the emergence of Europe (where the novel originated) from a ‘socially isolated and culturally deaf society and its entry into international and inter-lingual contacts and relationships’ (30). There is a sense to be gained from the novel of communication unhindered; it

|

is as if all the characters in it speak a single tongue – and this is true of Chapaev, in which everyone understands everyone else. The sense of polyphony to be got from Nail in the Boot arises out of a tacit admission that the plane of the action is an elevated one which the players have briefly ascended and only by common agreement. Chapaev is about people who are essentially like one.

If the general sense to be got from Chapaev is communication being unhindered with even the villains admitted within the same plane of understanding – although their loyalties are different – one’s immediate question is whether this can be associated with the notion of the ‘plot’ since the cinema of the pioneers was rebuked for being ‘plotless’. Since plot has broadly been associated with causal linkages in the narrative it can be argued that |

such linking is inhibited by the ‘dialogism’ in a polyphonic text in which there is not enough consonance between the voices for a single causal thread to be pursued (31). Chapaev’smonophonic character is reinforced by the use of character glance and facial compositions which help underline the sense of a common destiny. The steely resolve exhibited by the hard faces in Nail in the Boot point to a commonness of purpose, but it is purpose which is assumed over the resistance offered by the underlying polyphony and the multiplicity of destinies. In Chapaev, there is no indication that ‘resolve’ is necessary.

Between Nail in the Boot, in which polyphony is a natural condition - even if it is to be resisted - and Chapaev, something has apparently occurred and this is the moral ‘polarization’ of the citizenry. The social/ ideological agent causing the polarization is evidently the Soviet identity, which is still elusive in Nail in the Boot. It can be argued that the viewpoint treating ‘man as a machine’ will also deny a human being a ‘national identity’ and national identity may be a common agent across world cinema mediating directly or indirectly in plot construction and, consequently, inhibiting polyphony (32) – although this will need more investigation.

Soviet cinema under Stalin and its survival

Given the repression in the Stalin epoch – and the amount of red tape routinely required to be overcome – which lasted for two decades, how Soviet cinema survived as an intellectual force needs to be examined because it did not emerge aesthetically weakened but strong after Stalin.

As regards the studios – Mezhrabpomfilm in the early 1930s and Mosfilm later – there was a high degree of centralization which increased till the end of the 1930s until reform was necessitated by frequently paralyzed production. The reforms were not ideal and favored only senior filmmakers. Initially, after the reform, Mosfilm tried to be liberal towards films with questionable Soviet credentials but this too did not last (33). Another matter of importance is that of film education and training. By the end of the 1920s, the GTK (State School for Cinematography, Moscow) had become dominant. This had been a polytechnic – since cinema had still to prove itself as an academic discipline – but was made an institute in 1930 (GIK). With Shumyatsky as the head of the cinema administration, it became the Higher State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) with the Scientific Research Cinema Institute (NIKFI) integrated into it and a film library and historical archive also established alongside.

The cinema administration had the power to appoint the director of the Institute and give approval to important decisions, including those that concerned course content. But in practice leaders and teachers were given a great deal of autonomy in devising such content and in the day-to-day running of the Institute. Lecturers produced their own detailed programs, which were then approved by the director of the Institute and the cadres department at Soiuzkino (the cinema administration). Judging by the intellectual freedoms granted to figures such as Sergei Eisenstein, administration approval was essentially a formality. Lecturers and professors were often appointed on the basis of their reputation in the cinema industry rather than their perceived political reliability. The call for the establishment of a new generation of highly trained proletarian

|

specialists provoked a shift in educational policy towards securing for men and women from this background a significant quota of guaranteed places in higher education institutions and introducing a utilitarian approach that emphasized the connection between learning and industrial production, although this policy was reversed in 1932 because of its failure to produce high quality specialists. The mid-to-late 1930s saw the return of traditional academic standards in universities. Although the ideologically dictated policies of the administration (’the ‘cultural revolution’) brought it into conflict with the industry and the educational institutions, a broad consensus was still reached. In 1929, it had been decided that 75% of the seats in the VGIK and minor institutes would be reserved for people of proletarian origin and this had the support within the Institute as well as that of Eisenstein but by 1934 everyone concerned was in agreement that the policy was a failure. Most of the proletarian students had struggled to understand the |

academically challenging lectures given by figures such as Eisenstein, whose cross-disciplinary approach required a broad basic knowledge of theatre, art and literature and the drop-out rate went up to over 50%. The standard of the students needed to be approved and the solution was the establishment of an elite academy which would offer shorter two-year specialist courses aimed at individuals who had already received a higher education and had worked in cinema as assistants or in other branches of the arts. But the poor finances led to under-investment in the Institute and abysmal living conditions. The cumulative effect of these difficulties in film education and the cinema industry as a whole meant that graduates struggled to find work. The film-makers who had established themselves in the 1920s predominantly occupied the main posts in the studios, while those graduates of the 1930s who were employed were either sent to the dead-end studios in the republics where career opportunities were extremely limited or found themselves permanently in the role of assistants.

The future for new students was not bright but the teaching talent available at the Institute could not have been better. The status of the Institute as by far the most important establishment for the education of creative personnel from the Russian and the other Soviet republics was reflected in the wealth of teaching talent that it was able to attract in the 1930s. Many of the Institute’s key pedagogues in the 1930s had fallen out of favor with the cinema administration by the start of the decade, including Eisenstein, Lev Kuleshov and Abram Room. The cinematography faculty included Vladimir Nilsen as well as Eduard Tisse, Eisenstein’s great cinematographer. Paradoxically those personnel who were not trusted to make films for the new ‘cinema for the millions’ era were entrusted with the task of teaching the new generation who were intended to be the driving force behind the new industry. Eisenstein now played the central role in the VGIK. In the 1930s he was partly responsible for the shift from the less formal, spontaneous nature of film education, with its limited curriculum, experimental workshops, sometimes featuring tightrope walking, juggling and horse riding to a more organized, academically rigorous system based on longer courses akin to those in traditional universities with both undergraduate and postgraduate provision. One of Eisenstein’s most important measures was to broaden the curriculum far beyond the practical aspects of directorial work to embrace the entire spectrum of the arts, including literature, theatre, painting and music and specialist subjects such as Meyerhold’s biomechanics (34), a development of the Delsarte and Dalcroze approach to human movement. This involvement of the best filmmaking talent in pedagogy was not only at the VGIK but in the other institutes as well and teachers at the institutes included people like Mikhail Romm, Ivan Pyrev, Andrei Tarkovsky, Marlen Khutsiyev and Aleksei German himself and many of their students were also illustrious. Tarkovsky, for instance, was Romm’s student and he had Alexander Sokurov as a student. There was thus an unbroken tradition of the best talents of a generation passing on their skills to the next one.

Although political orthodoxy continued to exert itself, professionalism and creativity did not give way. All students entering the VGIK had to have a good knowledge of dialectical materialism. This influenced the content of certain courses especially the study of film history. In addition, other political pressures, such as the purges, did have an impact on the Institute. Despite this, the ethos of the Institute was one of broad learning and creativity. Although the immediate effect of film education was not felt by the industry in the 1930s, it was to have long-standing effects because it had created a body of filmmaking talent (35) and also incorporated the discoveries of the pioneers into formal learning.

As already indicated some of the biggest Soviet successes of the 1930s were musicals and melodramatic comedies and the directors associated with it were Grigori Alexandrov and Ivan Pyrev. Alexandrov had a smash hit with The Circus(1936) about a white American woman with a black child who flees the USA to be accepted in the USSR. The rural equivalents of Alexandrov’s urban musicals were made by Pyrev. The plots of Pyrev’s films were straightforward, all dealing with countryside romance against a background of collective farm development and conflict. Making the films popular was usually the music; for example, in The Circus, one of the opening compositions Song on the Cannon, has a distinct jazz feel. Another, more classical piece

entitled

|

The Lunar Waltz has a romanticism that reflects the heroine’s dream of a happy life beyond the racial hatred that she has known (in the US). If the political side was never abandoned even in the musicals, there was also more straightforward political propaganda like Pyrev’s infamous The Party Card (1936) about an ‘enemy of the people’ who steals his innocent friend Yasha’s girl and her party card on the instructions of a foreign spy. In making this contrast between the two men, Pyrev sought to convey the most important central message of this film: the Soviet citizen should never give in to spontaneous feelings or be tempted to explore dangerous paths as such choices will inevitably lead to negative consequences. Fridrikh Ermler, one of the pioneers of the 1920s (Fragments of Empire, 1927), who had become a reliable party filmmaker in the 1930s, made |

a two-part political epic The Great Citizen(1937-9) a fictionalized biography of Sergei Kirov, head of the party in Leningrad who was murdered in December 1934. Kirov’s murder (allegedly on Stalin’s orders although this is not proved) became a pretext for the great terror which commenced in 1936.

During the war years, Soviet cinema was completely mobilized towards the war effort – much more so than even in Germany, where also cinema was primarily an instrument of propaganda. It is interesting that when the allies won the war they found it necessary to ban only 208 Nazi-period films out of a total production of 1363 (36). Just how apolitical the majority of German films were can be gauged from the fact that the Soviets even distributed a majority of the captured films. There were reasons for why Stalin’s Russia, in which a vast majority of films made during the War were, in contrast, clearly propagandist. The most obvious ones were that the Nazis had ruled for a much shorter time and also did not have philosophy which claimed to be applicable in every walk of life. Unlike Stalin, Hitler and Goebbels did not have a coherent worldview to transmit to the public. Ideology had so permeated life in the Soviet Union that it was not even necessary to persuade the film industry greatly because filmmakers were willing to help in the war effort despite Stalinist repression. The first films to come out were documentaries in which the Soviet Union had enormous experience. It is reported the very first wartime newsreel made in the Soviet Union was shown three days after the commencement of the war, so well organized were the filming crews. After that, there was apparently a fresh newsreel every third day (37). Also, in contrast to documentaries from Germany and the other countries participating in the War which tried to emphasize victories, it suited Soviet documentaries to dwell on human misery, which is perhaps why they are still deeply moving from today’s distance. Also, many of the Russian films – especially those about battles fought in the worst conditions – were made far away but were still convincing – like Mark Donskoi’s The Rainbow (1944) which was set in Ukraine but actually shot in the studios at Alma-Ata. They may have helped here by the experiments of the pioneers – like Kuleshov’s ‘imaginary geography’. Donskoi’s film tells the story of a woman partisan, Olena, who returns to her village to give birth, where she is captured and subjected to the most dreadful torture, but does not betray her comrades. Rainbow has a powerful effect even on today’s audiences largely because of its unusually graphic and detailed depiction of Nazi barbarities. Soviet opinion-makers made the conscious decision not to allow the depiction of decent Germans. In 1942, Pudovkin used Brecht’s stories as a basis for a film entitled Murderers Go out on the Road that showed native victims of Hitler’s regime and fear among ordinary German citizens (38). The film was not allowed to be distributed. This is in stark contrast to how Germans were treated when World War I was the subject as in Boris Barnet’s Outskirts (1933), because that was in the context of the October Revolution which had largely benefited from anti-militarist sentiments.

Considering the other movies made at the time, it is extraordinary that Eisenstein was able to complete Ivan the Terrible (part I) in 1944. Eisenstein, too, aimed to show the victory of Russian arms, the importance of a heroic leader, but the film can also be read as partly allegorizing the internecine conspiracies and conflicts within the party. The second part of the film (shooting completed in 1946) goes much further in its depiction of the paranoid leader and was promptly banned, although the first part had received a prize. After the War and until after Stalin’s death in 1953, the people who had survived the war became tired of Utopias and desired nothing but ordinary life and ideological messages are played down.

The Thaw and after

The decade and a half after Stalin’s death (1953-68) is generally referred to as the ‘Thaw’ and a number of films made in this period show a marked departure from the motifs of Stalinist cinema. Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin at the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956 marked a new era and cinema blossomed for a decade. From the old guard, Sergei Eisenstein had died in 1950, Vsevelod Pudovkin in 1953 and Alexander Dovzhenko in 1956 but Mikhail Kalatozov and Fridrikh Ermler continued to work. The Soviet Union hardly abandoned Communism in Khrushchev’s period and the films contain much of the familiar but there is a new emphasis on domestic issues (39). In Marlen Khutsiyev’s Spring on Zarechnaya Street (1956), Tatyana is a Moscow girl who takes up the job of a teacher in a small town, where she is required to Russian literature to steel factory workers, and her conflict Sasha is the subject of the film. Making the film unusual is the discernible sense of threat from the workers to the educated woman, they undermining her authority in class with their proletarian masculinity. The class differences are however resolved when Tatyana visits Sasha in his factory (a staggeringly shot sequence) and the film returns to a celebration of production and the national identity. Spring on Zarechnaya Street is in black and white and if anything more can be said about it, it is about the quality of the camera work and the performances. The camera track effortlessly among the people in the crowd or party sequences and there are moments when the film even acquires the authenticity of a documentary although the treatment may have been expected to have been more sentimental like, say, Douglas Sirk’s All that Heaven Allows (1955), also a story of love across classes.

That Soviet cinema had the technical means at its command to rival the best in the world is also indicated by two films from Kalatozov – The Cranes are Flying (1957) and Letter Never Sent (1959). The first is a beautiful war film with love between a soldier (who dies) and the girl waiting for him but persuaded to marry another suitor as the principal motif, but the second film is more ambiguous and therefore deserves deeper scrutiny. In this film, a group of four young people are dropped off in Siberia to prospect for diamonds. Sabinine is older and their leader while Tanya and Andrei are geologists and in love. Sergei is their proletarian guide who falls in love with Tanya

|

while Andrei pretends not to see it. The letter in the title is the one written by Sabinine to the wife he has left behind and it becomes the means of narrating and conveying the emotions felt by the group. After many hardships and backbreaking exertion the group finally discovers diamond bearing minerals but that is when their travails actually begin because they are caught in a forest fire. The film emphasizes the spirit of discovery with the Soviet science as the inspiration but instead of arranging it so that the triumph follows the suffering it is the suffering that comes later. It is as if Kalatozov, while eulogizing collective life (without irony), is also suggesting that it guarantees nothing except perhaps a statue for oneself in a public place – although one cannot be sure that this is not acceptable compensation. The contempt expressed by Sergei towards Andrei for ignoring his advances to Tanya is also intriguing – especially because it |

remains unresolved. It is evident that one cannot evaluate the discourse in a Soviet film of the post-Stalin period without considering the possibility that there really was collective life and this transformed the nature of its citizens, perhaps making their desires and dreams difficult for those outside to fully comprehend. Another factor to be considered is that while the silent pioneers had developed highly individualized responses to film form, they were not ‘auteurs’ as we understand the term and all of them were characterized by faith in the same political philosophy. The importance of the auteur has perhaps been overestimated in cinema and many key filmmakers outside the West including those in Japan and the USSR cannot be distinguished by their personal concerns. In the Stalin era there were many exceptional filmmakers still working but their craft was inevitably subordinated to the purpose determined by the state. When the state loosened up under Khrushchev, they did not begin voicing their personal concerns but continued in the familiar way although there are changes in their approach. Kalatozov can perhaps be characterized in this way based on Letter Never Sent. In fact, the Khrushchev period has been compared to the 1920s because artists still had faith in the Revolution and dreamed of a utopian community (40).

The ‘difficult’ film

Nikita Khrushchev was deposed in 1964 and replaced by a collective leadership in which Leonid Brezhnev gradually ascended to the top position. Brezhnev resisted liberalization and reform and his rule is generally synonymous with decades of ‘stagnation’ at all levels. It would appear that the Soviet state weakened under his leadership and Russian nationalism – especially the religious variety – began to grow stronger. Marxism-Leninism had tried to co-opt nationalist tendencies into the system (41) but without much success and nationalism had remained indigestible. Instead of furthering the promise of the liberalization of the Khrushchev era, the 1970s and 1980s mark the period when the state was ineffective but ideological pressure on artists increased, together with petty-minded attempts to control every detail of their work (42). The range of free expression – which had only begun to be extended in the early 1960s – commenced to shrink, and every experimental work was suspected of undermining the system. Films were allowed to be made and without strict control over the script but they were then found to be unsuitable and suppressed or given a limited release where they went into obscurity. The suppression of a film like Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev (1971), which could only have been made with an approved (enormous) budget, could not have happened if the state administration had been fully in control because the film follows its screenplay quite closely (43). In the Stalin era, it must be recollected, the screenplay was the document to be scrutinized before a film project was approved.

Judging from what was said earlier it may be hypothesized that there was huge filmmaking talent available in the 1970s but with the Soviet state weakening, we may surmise that the scrutiny of projects had slackened considerably. ‘Personal expression’ which had not been much in evidence in Soviet cinema earlier, began to be gradually evidenced and this may be responsible for what has broadly been described as the ‘difficult film’ (44). It has been pointed out that there was a time when any new cinematic innovation was foreshadowed by a theoretical manifesto (45) but ideology and political philosophy had weakened considerably and artist practice had outpaced the manifesto.

By and large, ‘difficult film’ is the term used to describe works like those of Sergei Paradjanov beginning with Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1965) which have origins in folk culture from the republics but one can use the term more broadly to include films subscribing to systems which resisted subsumption under Maxism-Leninism and the Soviet identity inculcated under Stalin – including orthodox Christianity and Russian nationalism – and which now reappeared sometimes in covert forms since they had not found expression after 1917. Moreover, with Marxism-Leninism imperfectly imposed as a binding worldview, the filmmakers were tackling new subjects which Soviet cinema had not addressed. It must be reiterated that the Soviet films of the ‘Thaw’ period like those of Khutsiyev and Kalatozov are hardly ‘difficult’ not only because they still follow the regulation that makes accessibility primary but also because they demonstrate faith in the dominant worldview. It may be useful at this point to take a brief look at a particularly difficult film, Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror (1975) which has been described as ‘Russian nationalist’.

The Mirror is ostensibly autobiographical in many ways and begins with a boy with a stammer being made able to speak. The boy does not reappear and we may take it to represent Russians being cured of a ‘speech impediment’ although the couching of the notion in metaphor suggests that the cure is not complete. The story involves a dying man Aleksei in his forties reminiscing. He was five in 1935 when his father ‘left his mother’, which means that a part of the film is set in the world contemporary to it. The year 1935 has significance to Russia because it was the year in which the first arrests preceding the great terror began and Aleksei’s father ‘leaving’

suggests

|

his arrest although that is not spelt out. The best scene in the film is set in a printing press in which Aleksei’s mother works. She has been setting the types and fears that she has left in a word which should have been excised – a word she only whispers out to her friend. The important thing, however, is how ‘apolitical’ the film is despite Stalinist terror being invoked in the very first events recollected by the dying man, who is taken up more by his personal misconduct which caused pain to others, notably his wife whom he divorced. Also inserted into the film are newsreel segments – the Red Army on its advance at Lake Sivash in Ukraine, the Red Army in Berlin, Soviet |

border guards keeping off Chinese Red Guards during the cultural revolution. Since, in a section, the child Aleksei is made to read out a letter of Pushkin’s explaining Russia’s peculiar position – it being excluded from Western Christianity but saving the West from the Tartars whom it ‘swallowed up’, the film has been read as an affirmation of Russia’s importance to European civilization (46) and the newsreel footage also instantiates Russia’s sacrifices in this regard. The newsreel footage, unusual though it is, may also be a reflection upon the central role to which the newsreel was put in the Soviet Russia Union after the Revolution.

But the stranger aspect of The Mirror is that the protagonist’s ‘regrettable’ personal conduct should take up so much of Tarkovsky’s attention when the year in which the great terror was brewing – 1935 – and World War II are key events also dealt with – and there is no evidence that politics is being treated through metaphor to circumvent censorship. The issues of personal conduct and ‘spiritual salvation’ preoccupied Tarkovsky more than political issues because when he left Russia to work in Europe, his last film (The Sacrifice, 1986) ignores Russia and its politics altogether. A possible explanation is that the political and the personal were not discrete as they would be for a citizen in a representative democracy (47). The nurturing of ‘private space’ in a democracy, it can be argued, is possible because the citizens, in having exercised their franchise, are morally indemnified from the acts of the state, as it were, and their moral liability for its doings is perhaps akin to that of a shareholder in a limited liability company for the company’s debts. A totalitarian state instituted by a popular movement may be a different proposition and the public shares in the doings of the state. One is therefore allowed to speak of ‘innocent citizens’ in a democracy but one does not normally use the term ‘innocent’ to describe the citizens of Nazi Germany who also suffered greatly in World War II. The observation here is that state repression had begun even under Lenin with Felix Dzerzhinsky as head of the CHEKA; the Gulag system and the mass executions had commenced even during the Civil War. Leon Trotsky had warned (before he embraced Bolshevism) that if the Communist Party remained a ‘vanguard’ group above the people as envisaged by Lenin, it would eventually substitute itself for the people. A faction would then substitute itself for the party and an individual would eventually replace the faction and substitute himself for the entire people (48). The argument here is that the artists and intellectuals of the Soviet Union in the 1920s would certainly have known about the repression but felt that it was justified because their work shows them to have genuine faith in the Communist cause – even when their own kith and kin had to suffer under it. They saw totalitarian tyranny as a consequence of the system they had endorsed in their acceptance of collective life. As Russian film critic Alexander Timofeevsky observes, “The horror of Stalinism was not only that millions of people were exterminated, but that both hangmen and victims accepted their destinies as given” (49) and this might not have happened if the Soviet public had not felt responsible in some way for Stalinism. During Stalin’s last years, the Jewish wife of his aide VM Molotov was jailed even when her husband remained in favor. Given such a state of affairs in the Soviet milieu, the difference between a husband that ‘disappeared’ and one that ‘left’ in 1935 may not be so much. Tarkovsky’s film, it may be surmised, was dealing with Russian culture, the immediately political as well as the personal without the capability to keep the ‘personal’ separate from the ‘political’ and its ‘difficulty’ perhaps stems from it (50).

The return of polyphony

The notion of the polyphonic text which I raised earlier owes to Mikhail Bakhtin, a Soviet literary critic and philosopher who studied the novel. Bakhtin noted that the novel as a whole broke down under scrutiny into separate components: a) direct authorial literary narration, b) stylization of everyday oral narration, c) stylization of various forms of semi-literary everyday narration (letters, diaries, etc) d) various forms of extra-artistic, literary speech (maxims, scientific speech, legal memoranda etc) and e) the stylistically individualized speech of characters (51). Bakhtin did not restrict his study to Russian authors but also examined the works of writers like Charles Dickens (Little Dorrit) and concluded that a literary work is a site for the dialogic interaction of multiple voices which are the product of ‘multiple determinants specific to classes, social groups and speech communities’. But the ‘dialogic’ tendency or ‘polyphony’ cannot be informing every literary text equally and may thrive more visibly in milieus with greater exposure to foreign cultures. The Russian cultural elites had exposed themselves to European culture and this was a milieu favorable to ‘polyglossia’. Writers like Vladimir Nabokov are equally proficient in Russian, French and English. Also important is Russia’s racial, cultural and economic heterogeneity, which could assist texts to accommodate a multiplicity of voices. These are reasons for why texts from Russia may be more hospitable to polyphony but a more important issue still to be addressed in this enquiry is also how the same notion of the dialogism/ polyphonicity can be extended to cinema.

‘Polyphony’ suggests the interplay of different kinds of speech within a single verbal text but it is difficult to similarly conceive of different kinds of ‘speech’ in visual narration. But a film is narration as much as a novel is and there should still be a parallel of some sort. A solution is that since the teleology of a fiction film corresponds to ‘intent’ in authorial narration – because it is the course imposed on the narrative by the director of the film – the resistance to teleology, i.e. the interruptions in the narration and the elements which are not be ‘resolved’ will constitute the polyphonicity. As an instance, the trajectories of major characters not tied to the resolution of the story could represent polyphonicity. An immaculate plot, it must be noted, would proceed to eliminate these elements. There should be other ways in which polyphony is manifested and they will be examined but one could propose that the ‘difficulty’ of the difficult film is a first step towards polyphony – since it provides evidence of elements of discourse not subordinated to the dominant ideology.

It has been observed that in the Khrushchev period the intelligentsia still had faith in the revolution and while they opposed Stalinism, they did not oppose the communist state and the government and while they longed for democracy, they did not resist the totalitarian utopia under Khrushchev by focusing on the individual instead of the collective (52). They were still romantics and continued to see the ends of art as moral rather than aesthetic and without allowing for moral codes to be various – political, religious, social and private. It was in this climate that films – like Marlen Khutsiyev’s Illyich Square (1963) – that still believed in the communist utopia were suppressed (53) because they were misunderstood (54). The Khrushchev era tried to usher in a ‘moral revolution’ of sorts and while the intelligentsia was in Khrushchev’s favor, the socio-political apparatus resisted his efforts. The absence of the personal in the cinema of the Thaw period owes to the sense of a political utopia in which every aspect of the citizen might be involved. Brezhnev’s period of stagnation, because it promoted no utopian discourse with any conviction, paradoxically gave rise to individual expression, which was often suppressed quietly – like Tarkovsky’s The Mirror – and the hesitant reappearance of polyphony. I will now proceed to examine instances of how polyphonicity manifests itself in Russian cinema during glasnost, after the end of the USSR and until the present.

Polyphonicity under glasnost and after

Cinema was opened up to scrutiny as never before under glasnost and film critics attempted to take stock of what cinema meant. Since film had only played a serious role in society, there was little in the USSR which corresponded to ‘commercial cinema’ with segregation into distinct genres. Genres, in a sense, depend on audience segregation which occurs due to commercial considerations and cinema had been intended only to fulfill an ideological role for decades. Soviet genres like the industrial film, comedies, musicals and thrillers ignore the viewer’s psychology (55), which is essential to be taken note of in genres. Every genre was once directed towards what the viewer should see, which precludes the possibility of generic differentiation. Stated differently, genres create mythologies around different historical experiences which are often unconnected. It would, for instance, be difficult to make a historical association between the western and SF. Soviet cinema, because it promoted a single ideological discourse in relation to history, effectively prevented the formation of historically specific and independent genres. The films discussed in this last part of the essay therefore defeat generic categorization. But they have one aspect in common which is that they exhibit polyphonicity and my purpose now will be to describe the films and demonstrate it. The films discussed are all well-known and by important directors from the glasnost era and after (56).

Alexander Sokurov’s Days of Eclipse (1988)

This film is based on a science fiction novel by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky and published in 1974 called Definitely Maybe (also known as A Billion Years before the End of the World). In the book Leningrad astrophysicist Malyanov finds impediments being placed in his research. Approaching the problem scientifically, he suspects that his discovery is in the way of someone (or something) intent on preventing the completion of his work. The same idea occurs to his friends and acquaintances, who find themselves in a similar impasse some powerful, mysterious, and very

|

selective force impedes their work in fields ranging from biology to mathematical linguistics. An explanation is proposed by Malyanov’s friend and neighbor, the mathematician Vecherovsky. He proposes that the mysterious force is the Universe’s reaction to the mankind’s scientific pursuits, which threaten to destroy the fabric of the universe in some distant future. Vecherovsky proposes to treat this universal resistance to scientific progress as a natural phenomenon which can and should be investigated. Sokurov sets the story in a very poor region of Soviet Turkmenistan and makes Malyanov a doctor investigating the effects of religious practices on |

health. The thrust of the film now becomes covertly political because most of the characters in the story are people who were displaced and resettled in Turkmenistan during the Stalin era and the milieu seems entirely to be populated by resettled people. The focus of the film becoming medicine and biology instead of astrophysics has another consequence which arises out of biology having a larger interface with politics. The protagonist of the film is presented as an emissary of rationality in an irrational milieu who is blocked at every intersection. Sokurov sets up several bizarre scenes which are not explained – a boy eating pins which do not show up on the x-ray – and involving biological specimens like a monitor lizard, a the python, a claw shaped apparently reptilian creature preserved in hardened plastic and a monstrously shapeless organism putrefying an ancient wall inside a residence. The biological world is gaining upon science and, symbolically, Stalinist monuments loom at the edge of town – a concrete sickle and hammer, as if trying to obstruct the desert. The film’s purport is hardly self-evident but if the Strugatskys’ novel is about the resistance of the universe to science, the film can be interpreted as the resistance of an ‘irrational’ milieu to Soviet science and rationality.

Kira Muratova’s The Asthenic Syndrome (1990)

Muratova’s film has the distinction of being suppressed under glasnost for its ‘obscenity’ apparently on account of a long monologue towards the end which subtitled prints tend to tone down. The Asthenic Syndrome, which begins in sepia, initially focuses on Natasha, a doctor and widow, who has just buried her husband. Her reaction to his death is to rage at everything in sight. About a third of the way into the film, this is revealed to be a film being

shown to an

|

unresponsive audience which does not stay for the questions and answers, leaving behind only one spectator who is sleeping in his chair. The rest of Muratova’s film (now in color) is about the sleeping man, a failed novelist and a school teacher named Nikolai who is narcoleptic and tends to fall asleep abruptly, sometimes in the middle of trying situations. The film does not focus on Nikolai but is about his milieu and has been understood as a picture of Russia during glasnost. The Asthenic Syndrome is a difficult, extreme and almost incoherent film in which |

occurrences are sseemingly random and conversation is incessantly overlapping – with little that is being said providing clues as to its purport. But the effect is not nonsensical because everything still hangs together. By itself every utterance makes perfect sense to the person uttering the words and an instance is the teachers’ meeting at the school which Nikolai is sleeping through. In the first part of The Asthenic Syndrome – the film within the film – Natasha is shown to have gone off into angry ‘hysteria’ because her husband is young and his death is unexpected. She is shown looking at a series of pictures of the two of them together – arranged almost like a slide show – over a long period of time and also disrupting her home by breaking the glassware, etc. This film ends with Natasha putting her home in order again and there is a sense that the narrative interrupted by husband’s death can now commence differently. If the first part of The Asthenic Syndrome is regarded as a key to the second part – and there is no other sense which can be made of it – the second part constructed around Nikolai may be interpreted as being about a society which, because it is suddenly bereft of a grand narrative, exists only from moment to moment. That Natasha’s dead husband resembles Stalin supports this reading since the grand narrative of the Soviet Union in the Brezhnev era was still Stalinist. Nikolai being a ‘failed novelist’, i.e. his inability to complete a narrative of his own, can also be interpreted in this light.

Aleksei German’s Khrustalev, My Car! (1997)

Khrustalev, My Car! is about a Jewish surgeon named Major General Klenski who is implicated in the ‘doctor’s plot’ and arrested. A number of Jewish doctors were accused in 1953 of trying to poison the leaders of the Party and arrested but were absolved of the charges after Stalin’s death. Khrustalev, My Car! is a difficult film like the other two although in a different way. It is not formless but excruciatingly detailed in its depiction of Moscow life in the icy February of 1953. Instead of dealing with Klenski’s travails dramatically, it is as if the happenings in the street and the goings on in his household are as important as his horrific experiences

and the climactic

|

sequence at the dying Stalin’s bedside where he – as a doctor - is abruptly summoned, as he is being transported to the gulag. German uses deep focus and the tracking camera to provide a visceral picture of everyday life and his film can be interpreted as a depiction of a historical period in which no happening is privileged. A solitary crow on a branch is as significant as Klenski sodomized by his fellow prisoners or Stalin soiling his sheets in the concluding moment of his life. The effort is to rely entirely on ‘remembered history’ and ridding the past of its historicist overlay, and this becomes significant in the light of how history was used in the USSR.

|

Aleksei Balabanov’s Cargo 200 (2007).

Cargo 200 is not a ‘difficult’ film like the other three just dealt with. It is set in 1984 in the Soviet Union just after Yuri Andropov’s death, with the nation still embroiled in Afghanistan and the title pertains to dead soldiers returning from Kabul in lead lined coffins. The film has been described as a ‘thriller’ but it is closer to the horror genre with Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) perhaps being its most recognizable relative. The action revolves around two young people Angelika and Valera and their adventures after the two decide to go in the dead of night to an illicit distiller to get some vodka. Angelika is kidnapped by a mad police (militia) captain who puts her through unimaginable horrors in the name of ‘love’. The film relies for its horror on the

|

sense of the marginalized spaces but unlike Tobe Hooper’s film, Cargo 200 has other strands which make it highly political. Angelika is the daughter of the local Party secretary; central to the film is also a long dialogue between the bootlegger Aleksey and Artem, a professor of ‘Scientific Atheism’ from Leningrad University – on religion and rationality. The film is set in a fictional industrial town named Leninsk and the narrative is punctuated by impersonal shots of its giant industrial complex, freight cars going incessantly to and from it.

A characteristic of Cargo 200 that takes it away from the genre of the horror film and brings it closer to |

surrealism is its tone of darkly comic irony. Angelika is not innocent as the protagonists of horror films (including Hooper’s film) usually are but is the privileged representative of a system in collapse. She undergoes the experiences not in some remote location but in almost familiar terrain. The slumbering state and the party have become so alienated from the society of their own creation that social mutants thrive under their very noses. Balabanov steadfastly refuses to take sides - between the innocent victims and the perpetrators - because the victims in this case are actually implicated the creation of the monsters. The dialogue between Artem and Aleksey also furnishes an ironic discursive backdrop before which the horrific central drama is enacted – suggesting the hideous festering taking place in a society where the state promoted rationalism for decades.

The four films just described share an attribute which is that all of them deal with a collapse of order. Cargo 200 provides the most precise portrayal of a ‘collapse’ because it is about a political collapse, which is easier to comprehend directly. But its precision is because it is able to survey the collapse – that of the USSR – from a much greater distance, when the new Russian state had also stabilized. The remaining films deal with other aspects of the collapse and the nebulousness of their concerns makes them more difficult. Days of Eclipse is centered on the impending collapse of the grand narrative of Soviet science and – as already argued – The Asthenic Syndrome is also about the collapse of a grand narrative. Aleksei German’s Khrustalev, My Car! is nominally about the last moments of the Stalin era but the form it chooses for itself is itself an exposition on the collapse of Marxist-Leninist historicism and the release of personal memory. The collapse of order therefore creates the polyphony – voices not subordinated to rationality, science or history – but this would hardly have been possible if Soviet cinema had not already reached the level of sophistication required to give voice to the experience.

Conclusion: Ambiguity and polyphonicity

The ‘difficult films’ from the USSR of the glasnost period and Russia of the Yeltsin/ Putin era are difficult in a different way from the ‘ambiguous’ films of post-war art cinema from Europe – viz. those of filmmakers like Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman or Jean-Luc Godard. It has been convincingly shown (57) that art cinema defines itself explicitly against the classical Hollywood narrative mode, especially with regard to the cause-effect linkage between events. Art cinema motivates its narratives through two central principles – realism and authorial expressivity. It is plausible in a real situation that a detective is run over accidentally by a truck when he is at the point of solving a crime. But while such a turn will not be permitted in a classical detective story – which insists on a moral order being affirmed by the narrative – it could happen in a film by Antonioni. Another ‘realistic’ deviation from classical storytelling is in art cinema’s characters not being clearly motivated. The art film foregrounds the ‘author’ as an organizing intelligence, and ‘ambiguity’ is the constituent of narration which allows us to interpret authorial intent. When art cinema consciously violates classical film convention, it forces the spectator to interpret these violations in terms of authorial expression.

It should be evident that the ‘difficulties’ of the Soviet/Russian films described are not identifiable with the ‘ambiguities’ posited by European art cinema. Where the strategies of the European art filmmaker, which revolve around authorial expression, presuppose a socio-political milieu constant enough to pursue preoccupations which, even if they are not entirely ‘personal’, principally assume a stable private space, the Soviet/Russian filmmakers of the post-Soviet era were grappling with a milieu transformed and rendered unstable after decades in which ‘private life’ had been subordinated to a common historical purpose. The ambiguity of the European art film and the polyphonicity of Russian cinema both owe to an engagement with the complexity of the world but while the former is like a product of undisturbed contemplation, the latter is an actual struggle with the disturbance. The Asthenic Syndrome was widely understood as a portrayal of life under glasnost, but Western critics also admitted its ‘universality’. This means that if Muratova’s film is an exploration of an extreme social condition, the condition is still identifiable to those outside Russia – just as Dostoyevsky’s characters are recognizable even if we have met none like them.