|

“….kaladrishtini, vyaparadrishtinimelavinchi, Telugudanamtoparimalinche

Telugu filmulanitayarucheyali.”

(‘…aesthetic and commercial sense must be combined to make Telugu films which have the fragrance of Telugu-ness’)

-- Gudavalli Ramabrahmam1

Cinema started talking and this newfound voice of film brought with it new changes. In the West, sound invading the screen elicited varied reactions2 but in India, filmmakers responded to the human voice in a manner different from their western counterparts. Instead of regretting that the ‘talkie’ was a degenerate form of theatre3, Indian filmmakers maneuvered the Indian talkie  precisely in that direction – and popular theatrical productions were promptly brought to the screen. However, as noted by Stephen Hughes and cited by SV Srinivas, “In contrast to the fluid and overlapping multilingualism of silent film, sound forced Indian film producers to address new and still uncertain market conditions, which were simultaneously enabled and restricted by linguistic factors.”4 Suddenly, it was not enough for Indian films to be merely Indian and they had to be regional too: Hindi, Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, etc. While the earliest sound films, even those in which the actors spoke south Indian languages, were made in studios located in Bombay, by the mid-1930’s Madras became the central location from which Tamil as well as Telugu films were being made. Srinivas argues that “[t]here was no such thing as the ‘Telugu’ film industry in the 1930’s.”5 So, a question naturally arises: what were the factors involved in making the Telugu cinema ‘Telugu’? precisely in that direction – and popular theatrical productions were promptly brought to the screen. However, as noted by Stephen Hughes and cited by SV Srinivas, “In contrast to the fluid and overlapping multilingualism of silent film, sound forced Indian film producers to address new and still uncertain market conditions, which were simultaneously enabled and restricted by linguistic factors.”4 Suddenly, it was not enough for Indian films to be merely Indian and they had to be regional too: Hindi, Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, etc. While the earliest sound films, even those in which the actors spoke south Indian languages, were made in studios located in Bombay, by the mid-1930’s Madras became the central location from which Tamil as well as Telugu films were being made. Srinivas argues that “[t]here was no such thing as the ‘Telugu’ film industry in the 1930’s.”5 So, a question naturally arises: what were the factors involved in making the Telugu cinema ‘Telugu’?

This essay is primarily about the dialogue between Kuchipudi and Telugu Cinema but it also addresses the above question raised by Srinivas, and therefore relies extensively on his work. In the process of gathering data and information for the larger project concerning Kuchpudi and Telugu cinema certain questions recur time and again. One of them concerns the foray of Kuchipudi into the film world which historians of Kuchipudi have explained away through economic reasons.6 The question whether this is the whole truth or if it was partially contributed to by aesthetic issues is beyond the scope of this article. However, the question that pushed the inquiry in this specific direction is the other half of the equation - why film engaged with the performing art of Kuchipudi. As Srinivas notes, from the perspective of all the human sciences and not just film or cultural studies, the Telugu state has been understudied in comparison with both Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Other than Lisa Mitchell (2009)7, there has not been much quality academic writing on the state’s politics or on contemporary Telugu-language writing, whether literary or pertaining to films and the media;8 dance in Telugu cinema appears to be even more neglected. None of the few works on the Telugu film even acknowledge the conspicuous presence of dance in this industry, except for rare and passing mentions of the dance directors/dancers. But, as will be seen, the reasons for the coming together of these two visual performing art forms were deeper than what strikes the eye at first glance.

Reverting back to the previous question of the Telugu-ness or Telugudanam of Telugu cinema it can be proposed that the specific regional flavor that Telugu cinema later acquired had not yet been defined. Especially in the wake of the work of Mitchell (2009), which contests the widely-accepted  notion that the mother tongue is central to the individual’s identity it has become clear that the very form of Telugu-ness had not yet stabilized when ‘Telugu’ cinema arrived. In fact, the inverse is apparently true: i.e. that Telugu cinema played a major role in constructing the concept of Telugu-ness. In other words, just as ‘Telugu’ became an indentifying marker for an individual who spoke the language only by the early decades of the 19th century, Telugu cinema contributed by providing visual images to what constitutes the Telugudanam of Telugu people. In other words, just as Telugu shifted from being a medium to being a marker of identity Telugu cinema threw forth numerousaesthetic-cultural aspects that would come to be identified as markers of Telugu-ness in the times to come. Accessing and analyzing a variety of source materials Srinivas discusses in great detail the work, both in the writing and cinema, of Gudavalli Ramabrahmam who played a central role in bringing forth the question of what is known, even till today, as the Telugu ‘nativity’ of Telugu cinema. notion that the mother tongue is central to the individual’s identity it has become clear that the very form of Telugu-ness had not yet stabilized when ‘Telugu’ cinema arrived. In fact, the inverse is apparently true: i.e. that Telugu cinema played a major role in constructing the concept of Telugu-ness. In other words, just as ‘Telugu’ became an indentifying marker for an individual who spoke the language only by the early decades of the 19th century, Telugu cinema contributed by providing visual images to what constitutes the Telugudanam of Telugu people. In other words, just as Telugu shifted from being a medium to being a marker of identity Telugu cinema threw forth numerousaesthetic-cultural aspects that would come to be identified as markers of Telugu-ness in the times to come. Accessing and analyzing a variety of source materials Srinivas discusses in great detail the work, both in the writing and cinema, of Gudavalli Ramabrahmam who played a central role in bringing forth the question of what is known, even till today, as the Telugu ‘nativity’ of Telugu cinema.

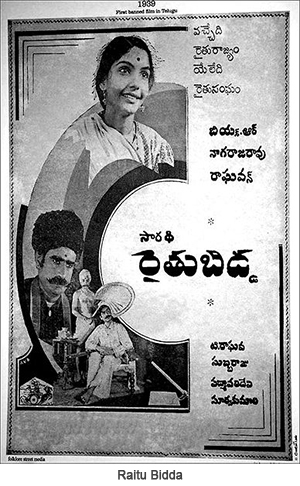

Ramabrahmam – a public intellectual, business manager and editor – was from the Kamma caste and from the Telugu speaking regions of the Madras Presidency. He was an individual who had considerable standing even before he became a film director9. He became the director of Malapilla (1938), which was the film that announced ‘the arrival of the social as the form committed to nationalism,’10 and followed it up with Raitubidda (1939), a landmark film in the history of two of the most popular art forms of the Telugus – their cinema and their classical dance. Addressing the issue of the economic crisis faced by the film industry Ramabrahmam attributed it to three mains factors – too many film halls, films that did not rise up to audience tastes, and the lack of specialty, distinctiveness and national character – pratyekata, visishtata and jatiyata – in Telugu films. The last factor was for him of particular concern, as Telugu films being made in Madras could not possibly be sufficiently ‘Telugu’. In his article, from which the opening quote of this essay is borrowed, the director expresses frustration at having to deal with issues which the Telugu film-makers at the time faced, owing to their location being in a predominantly Tamil speaking region.

“Ramabrahmam makes a sarcastic passing reference to the claim of Presidency Telugus over Madras and cites an amusing example to show how the city did not support the production of on-screen Teluguness. During the making of his Raitubidda, which he points out was shot in a studio that he himself managed (Vel Pictures), the Madras extras did not know how to tie their dhotis like the Telugu peasants they were supposed to be playing on screen. Surely, he remarks, he was not spending hundreds of rupees a day to hire extras and feed them too in order to teach them to tie their gocheelu (loincloth)! It was pointless arguing about pratyekata and visishtata when the day was spent adjusting loincloths. Telugus therefore needed their own studio on their land…”11

Kodavatiganti Kutumbarao, more popular by the name of Koku in film circles, in a 1953 essay, elaborates on the same problem: “the fields were different, the cart and bullocks, the whip and the plough were different – everything was different.”(emphasis added).12 He further says, “In Madras non-Andhras work as art directors. Our films fail to show Telugu peasants, middle class Telugus and their houses”13 (emphasis added). Koku specifically mentioning that the art directors needed to know what Telugu-ness was indicates that the realization that more than the words and actors in cinema needed to be Telugu had already dawned. The major hurdle that Telugu cinema was facing at the time was that the actors “… were speaking Telugu on screen, but not being Telugu.”14Koku apparently attributed this discovery to Ramabrahmam while he was shooting Raitubidda. Other sources nonetheless suggest that Ramabrahmam discovered the necessity of being Telugu (and not merely speaking the language) in cinema even before Raitubidda was made and that he also realized that although ploughs, carts, bullocks and houses could not be brought to the set from ‘Andhra,’ other ingredients contributing to Telugu-ness on the screen could, in fact, be brought to Madras.

Vedantam Raghavayya, who is more popular today for his directorial successes in Telugu cinema, entered the industry as a performer. In an interview with Vijayachitra,15Raghavayya describes in detail his initial encounters with film. He was first recommended for a movie titled Mohinirukmangada16 in which he danced the Balagopalatarangam17 in the attire used for female impersonation. It was a ‘direct take’ Raghavayya says, and describes it as being ridiculous (hasyaspadam), which drove the entire Kuchipudi community to take the decision never to have anything to do with cinema again. But Ramabrahmam willed otherwise. Earlier, in 1932, Nageswara Rao Pantulu and Dr. Govindarajula Subbarao had organized natyakalaparishats (drama seminars) in Madras, in which Raghavayya participated on the recommendation of Gudavalli Ramabrahmam. Raghavayya even recounts that he performed the Balagopalatarangam and the yakshaganam of Usha Parinayam in this seminar. This incident points at two things – the first is that Raghavayya was already, by the very early 1930’s, a performer of Kuchipudi who had gained a certain reputation; and, secondly, that Ramabrahmam had identified the fact that Raghavayya (and in turn Kuchipudi) could be representative of the Telugu performing tradition. Thus, when Ramabrahmam embarked on his first directorial venture, he approached Raghavayya to be a part of the film Malapilla. However, he was turned down owing to the unfortunate first encounter Raghavayya had had with film. Not to be deterred, while making Raitubidda, “Ramabrahmam waited at the outskirts of the village of Kuchipudi, discreetly sent word for me (Raghavayya), took me in a car to Bejawada (Vijayawada), and made me sign an agreement. In Raitubidda, the Dasavatara Sabdam proved to be satisfactory, and brought publicity.”18 The Dasavatara Sabdam, interestingly, is performed by Raghavayya in male attire “reminiscent of the Orientalist aesthetic Uday Shankar was popularizing in the early twentieth century.”19 This choice of costume could have been prompted, as described by Putcha, by the pan-Indian trends in dance (that definitely had their influence on the Kuchipudi performing art), as also by the fact that Raghavayya still had the taste of his bitter experience in Mohinirukmangada20 and was wary. The screenplay of Raitubidda explains in its dialogue the inclusion of the dance sequence drawn from the Kuchipudi repertoire by a hereditary Kuchipudi artiste in a temple, for the benefit of the entire population of the village: “the Zamindar has organized a dance performance by the Kuchipudi Bhagavatulu. Let’s find out what it is about.” There is another bit of dialogue in the movie which specifically mentions the name of Kuchipudi. Sundaramma, a young lady, dances to the song Vayinchuma Murali Vaayinchu (‘Please continue to play the flute’) in her home. The dance is choreographed by N. Chimanlal and does not (intentionally or otherwise) have a strictly patterned choreography. Her brother who sees her dancing by herself chides her but her mother pacifies the girl by promising to ‘engage a Kuchipudi Bhagavatulu to teach her dance, and that she need not take offence at her brother’s words.’ In another scene, this Kuchipudi Bhagavtudu, played by Raghavayya again, is seen teaching Sundaramma the Kshetrayyapadam, Innalla vale kadamma (‘He is not the same as he was until recently’), while the mother watches them. Following a couple of repetitions of this padam, the mother pleads with Raghavayya to teach her daughter well and make her a dancer of an acceptably high standard, so that she can be ‘settled’ in life, and that they would be grateful to him for doing so. The film credits for this film include a separate frame displaying the following words in quite a large font, ‘Bharatanatyam21 by Vedantam Raghavayya of Kuchipudi.’ The various dialogues described above along with the dance sequence in this 1939 film “supports the normative history of Kuchipudi… (that) not only characterizes the men of Kuchipudi as respected performers for patrons, like the zamindar, but also as high-caste, Brahmin dance teachers to lower-caste female dancers….Raitubidda has provided a visual narrative to what has since become the identity of the Kuchipudi tradition.”22 The implications that this film, made by a prominent director, has had on the worlds of Kuchipudi and Telugu cinema are multifold. While it proved to the Kuchipudi artistes that their skills could, in fact, suit the requirements of the celluloid medium, it also succeeded in providing the dance form, and its artistes, with the required acceptability within film circles. Following this, Raghavayya became a sought-after performer and dance director in films, and other Kuchipudi artists were also quick to enter the film world themselves. Vempati Peda Satyam and Pasumarthy Krishnamurthy entered the industry in the early 1940’s and succeeded in creating a niche for themselves. Vempati Chinna Satyam and Vedantam Jagannatha Sarma too made attempts to follow the same path, but later withdrew to become teachers and choreographers in Madras and Hyderabad respectively. Over the next thirty years, between 1939 and 1969, Kuchipudi artists and Telugu cinema engaged in a substantial dialogue with each other which left indelible, and as yet undiscovered, imprints on each other.

The various shifts that occurred in the course of Kuchipudi through which it transformed into another marker of the ‘Telugu’ people – ‘their classical dance form’ - during the period mentioned above is not the subject of discussion here; rather, what hereditary Kuchipudi artists brought with them to the film industry will be the relevant point. These artists interacted with cinema not just as performers in random dance sequences but also became choreographers, or ‘dance directors’ for films. As described above, their precise job description at the beginning of their entry point into the film industry was to boost the levels of Telugudanam in Telugu films. They certainly did that, and much more. The incredible dexterity of the hereditary Kuchipudi artists to draw elements from the various genres/forms of art that exist parallel to their own, with an acute sense of the contextual requirements was the reason behind their prolonged and vibrant career in the film industry. They brought with them not just the elements of Kuchipudi’s theatricality and dance, but also the music employed in the Kuchipudi art form. Instances of thematic dances in films that were composed on the lines of a yakshagana23 are too many to be cited. Vedantam Raghavayya’s stint as a performer and dance director was during the very late 1930’s and early 1940’s, a period in which the solo had not yet arrived in Kuchipudi performance. Thus, he drew largely from the movement vocabulary of the mejuvani dance tradition prevalent in the Telugu speaking regions of .jpg) the Madras Presidency. An example of such choreography can be seen in the padam Manchidinamunede (‘This is a good day’) from the film Swargaseema (1945). The choreography for this dance is almost entirely based on the female courtesan dance traditions. Vempati Peda Satyam, owing to his exposure to the schools of Uday Shankar and Ramgopal combined with his obsession for form which he retained from his training in painting under Adavi Bapiraju, brought to his choreographic efforts a certain complexity and ‘sculpturesque’ quality, not found in any other’s work. One of the best examples of such choreography is a Siva Tandavam from SreeVenkateswara Mahatyam (1960), in which Peda Satyam himself performed as Siva. Pasumarthy Krishnamurthy retained his own native elements of Kuchipudi and its music/dance for the major part of his work. Yet, all the three of them choreographed numerous dances that are reminiscent of tribal, folk, rock-n-roll and ‘cabaret’, among others. Krishnamurthy even performed a rock-n-roll number with a dancer by the name Tulasi, in the 1952 film Palleturu. Their selling point, or ‘USP’ as it is now popularly called, lay not in merely reproducing versions of the art they brought from the performance culture in Kuchipudi but in creating versions of the kind of dance that a particular context in a particular movie demanded and required. the Madras Presidency. An example of such choreography can be seen in the padam Manchidinamunede (‘This is a good day’) from the film Swargaseema (1945). The choreography for this dance is almost entirely based on the female courtesan dance traditions. Vempati Peda Satyam, owing to his exposure to the schools of Uday Shankar and Ramgopal combined with his obsession for form which he retained from his training in painting under Adavi Bapiraju, brought to his choreographic efforts a certain complexity and ‘sculpturesque’ quality, not found in any other’s work. One of the best examples of such choreography is a Siva Tandavam from SreeVenkateswara Mahatyam (1960), in which Peda Satyam himself performed as Siva. Pasumarthy Krishnamurthy retained his own native elements of Kuchipudi and its music/dance for the major part of his work. Yet, all the three of them choreographed numerous dances that are reminiscent of tribal, folk, rock-n-roll and ‘cabaret’, among others. Krishnamurthy even performed a rock-n-roll number with a dancer by the name Tulasi, in the 1952 film Palleturu. Their selling point, or ‘USP’ as it is now popularly called, lay not in merely reproducing versions of the art they brought from the performance culture in Kuchipudi but in creating versions of the kind of dance that a particular context in a particular movie demanded and required.

In the early stages of film production, when studios employed artists/technicians were on monthly payment these Kuchipudi artists were giving the actresses training in both dance and acting24. They performed in numerous dances themselves over the course of their careers,25 and Pasumarthy Krishnamurthy provided also playback for some songs26. Vempati Peda Satyam was the asthananatyacharya (dance director) for NAT Productions, as Pasumarthy Krishnamurthy was for Vijaya Pictures. Vedantam Raghavayya moved further up the ladder and became a film director, and directed most of his films with the production house of Anjali Pictures27. The various spheres of film-making with which the Kuchipudi artists participated is only too evident; yet, with the sole exception of Vedantam Raghavayya, none of them had any consequential role in the industry except as ‘dance directors’. The above enumerated encounters they had with film as performers in dance sequences, playback singers, even what could be termed ‘assistant’ music composers for yakshaganas and other indigenous musical traditions depicted on screen, are evident only when looked for – and they are overlooked in the historical narratives of cinema. Also, the fact that other hereditary Kuchipudi artists made attempts to enter the film industry in other departments came up in the numerous interviews conducted in the village of Kuchipudi. Bokka Kumaraswamy, a violinist/musician who belonged to one of the hereditary families underwent many trials to become a part of the cinema’s music industry, but failed. Vedantam Ramakrishnayya, another hereditary artist known for his prowess as an actor did enter the  industry with the film Mayabazar (1936), but also exited after it. The only hereditary artist who made a career in films in what is termed a character actor is Mahankali Venkayya28. In fact, Kuchipudi artists were not just dancers, they were equally, if not more, skilled in the fields of acting, music, lyric writing etc. But the argument offered to explain the acknowledged presence of these artists only as film dance directors is that the industry did not need them to engage with any other aspect of film-making. It had designated a specific role for these Kuchipudi artists - that of the dance directors (choreographers or even gurus). In other words, it wanted them to be representatives of the dance of the Telugus, a dance which could be learnt by the many middle-class young girls belonging to the Telugu families, who were to be the representatives or embodiments of the Telugu culture. In doing so, cinema influenced the selection of a vital aspect of the Telugu people – their classical dance, which would be one of their prime markers, representing them on the cultural map of India. industry with the film Mayabazar (1936), but also exited after it. The only hereditary artist who made a career in films in what is termed a character actor is Mahankali Venkayya28. In fact, Kuchipudi artists were not just dancers, they were equally, if not more, skilled in the fields of acting, music, lyric writing etc. But the argument offered to explain the acknowledged presence of these artists only as film dance directors is that the industry did not need them to engage with any other aspect of film-making. It had designated a specific role for these Kuchipudi artists - that of the dance directors (choreographers or even gurus). In other words, it wanted them to be representatives of the dance of the Telugus, a dance which could be learnt by the many middle-class young girls belonging to the Telugu families, who were to be the representatives or embodiments of the Telugu culture. In doing so, cinema influenced the selection of a vital aspect of the Telugu people – their classical dance, which would be one of their prime markers, representing them on the cultural map of India.

Another of those questions begging to be answered is ‘why only Kuchipudi?’ There were other performing art traditions29 that could provide the aesthetic that Telugu films required at that time. Why was Kuchipudi ‘the chosen one’? To delve into this history, the reform movements that were being taken up by social reformers at the time in the pan-Indian scenario must be referred to. Many studies have traced the anti-devadasi movement that gained immense prominence in the Madras Presidency by the early decades of the 20th century. In the present context, it is necessary to draw attention to two factors – firstly, there was an incredible amount of social stigma attached to the castes of the hereditary female performing artists by the early decades of the 20th century in both Telugu and Tamil speaking regions of the Presidency. Tamil cinema found a solution to this problem by engaging the male nattuvanars30 of the time as dance directors in cinema. Secondly, in the Telugu speaking regions of the Presidency, there was notradition of nattuvanars being the dance gurus31 in the hereditary female dance families. Instead, the leader of the troupe was the nayakuraalu, usually the elder woman of the family. The cinema industry (along with the individuals involved in the Telugu reformist movements) found a solution to this problem by choosing the other elite performing tradition32 from the Telugu speaking regions. And they got lucky – not only were these performers male, but they also belonged to an entirely different class and caste background, the Smartha Brahmin, which was completely different from the sani/bhogam communities. Thus, Kuchipudi becoming a part of the Telugu cinema industry was, by no means, a mere coincidence, nor was it because the film simply brought together the greats from varied art forms. Kuchipudi was chosen through a carefully and meticulously conducted process of ‘auditioning’ and ‘selecting’.

The last and final question this article seeks to answer was raised only by academics from the departments of film studies – Kuchipudi historians never paid attention to the fact that the Kuchipudi artists did not continue being a part of the Telugu film industry after 1970. Biographically speaking, Raghavayya died in 1972, Vempati Peda Satyam moved back to his village of Kuchipudi, selling away all his property in Madras, in the mid 1970’s, with an intention to become a full time guru in the dance school that was established there by the government. Pasumarthy Krishnamurthy continued to live in Madras, till 2004, when he passed away. Yet, post the 1970’s, hereditary Kuchipudi artists, or even artists trained in Kuchipudi, were commissioned by the film industry only for specific films, and by specific directors. To cite a few examples, Krishnamurthy and V. Seshu Parupalli33 were the dance directors for most of K. Viswanath’s movies, which had classical dance/music as their central theme.34 Further, Krishnamurthy was commissioned for folklores and mythological films, like Bhairavadweepam (1994) and Balaramayanam(1996). In an interview with Singitam Srinivasa Rao, a prominent Telugu film director now settled in Chennai, this question elicited a response that points to the changes in film-making processes. “In the movie America Ammayi, we asked Vempati Chinna Satyam to choreograph the dance sequence for the song Anandatandavamaade, as it was to be a purely classical dance. We also asked Krishnamurthy to be the dance director for the other songs. But, during the shooting, we found that he was extremely unhappy with the standard of the dancers booked for the songs. He became quite impatient. You see, the trends had changed, film didn’t require their kind of dancing anymore, except for songs like the classical dance in the movie, which became a huge hit.”35 Such ideas expressed in similar interviews are in sync another argument offered by Srinivas. Post the formation of Andhra Pradesh, “… the equivalence between popularity of films and Telugu-ness became a possibility: films were popular among Telugu people and therefore Telugu.” The film did not have to worry about the on-screen Telugu-ness, did not require songs/dances etc. filled with the Telugu fragrance. It was a given that as Telugu films involved Telugu crew, and were watched by Telugu people, the films had enough Telugu-ness. This raises another question regarding the Kuchipudi artists – why could they not, like their predecessors, mould their art according to the requirements of the changing trends in cinema. The answer to this is simple – classicization, and consequently, canonization. The form that had an unending capacity to bring forth new genres in performance was structured to suit certain requirements demanded by classicization, and so the later generations of artists could not break away from that mold. Thus, these Kuchipudi artists are remembered if, and only if, there is a need for ‘classical’ dance to be choreographed in Telugu cinema. In 2010 K. Viswanath commissioned Vedantam Venkatachalapthi36 to choreograph dances for the film Subhapradam, which begins with the song AmbaParaku, a traditional invocatory that is sung before commencing any Kuchipudi performance. Though Venkatachalapthi also choreographed other dances in the film, K. Viswanath said that “it had been my dream to have this song as a beginning for one of my films, but it never happened. So I have asked him to choreograph and also dance in it as the sutradhara. As for the orchestra too, I wanted a complete Kuchipudi orchestra. Balasubrahmaniam can sing the song, but I wanted Sastry37 to sing it….because a regular film orchestra cannot produce the nativity required for this song.”38 (emphasis added)

Nativity – that term again, one that still brings to mind the Kuchipudi Bhagavatulu in those rare and far-in between occurrences when ‘Telugu classical dance’ is featured on the silver screen. It can be safely stated that, all those decades ago, Ramabrahmam plotting the willing ‘abduction’ of Vedantam Raghavayya proved to be, in no terms, an inconsequential act.

Notes/references: Notes/references:

| 1. |

Gudavalli Ramabrahmam, “Telugu Film Parisrama Labhadayikamga Undalante.” (Tel.) Andhra Patrika. Vikrama Samvatsaradi Sanchika [Special Annual Issue 1940], pp. 95 – 9. Cited by Srinivas:53.

|

| 2. |

Paul Rotha, the ‘British Cinema Pundit’ lamented: “A film in which the speech and sound effects are perfectly synchronized and coincide with their visual image on screen is absolutely contrary to the aims of cinema. It is a degenerate and misguided attempt to destroy the real use of the film and cannot be accepted…” Ironically, even those filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock who later became successful filmmakers too, initially expressed poor opinions of films using the voice. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sound_film#cite_ref-146

Accessed 26.03.2015 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sound_film#cite_ref-147

|

| 3. |

Max Reinhardt, German Stage producer and Movie Director viewed the sound film as “bringing to the screen stage plays…tend to make this independent art a subsidiary of the theater and really make it only a substitute for the theater instead of an art itself…” Accessed 26.03.2015 en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sound_film#cite_ref-148.

|

| 4. |

S.V. Srinivas, Politics as Performance: A Social History of the Telugu Cinema, Permanent Black, 2013, p 58.

|

| 5. |

Ibid, p 19.

|

| 6. |

Anuradha Jonnalagadda “Tradition and Innovations in Kuchipudi Dance” Ph.d. Dissertation, University of Hyderabad, 1996, p 47.

|

| 7. |

Lisa Mitchell, Language Emotion and Politics in South India: The Making of a Mother Tongue, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

|

| 8. |

S.V. Srinivas, Politics as Performance: A Social History of the Telugu Cinema, p 9.

|

| 9. |

Even before Malapilla was made, Ramabrahmam was called a “veteran Telugu Director.” S.V. Srinivas, Politics as Performance: A Social History of the Telugu Cinema, p 29.

|

| 10. |

Ibid, 114.

|

| 11. |

Ibid, 53.

|

| 12. |

Ibid, 61.

|

| 13. |

Ibid, 61.

|

| 14. |

Ibid, 61.

|

| 15. |

Vedantam Raghavayya, “Naa Tholi Cinema Anubhavam”, Vijayachitra, n.d.

|

| 16. |

Mohini Rukmangada (1937) produced by National Movietone.

|

| 17. |

One of the most popular solo numbers in the Kuchipudi repertoire, drawn from Narayana Teertha’s 17th century work, “Sri Krishna Leela Tarangini,” a part of which the dancer dances on a brass plate while balancing a water filled pot on the head.

|

| 18. |

Vedantam Raghavayya, “Naa Tholi Cinema Anubhavam” Vijayachitra, n.d.

|

| 19. |

Rumya Putcha, “Revisiting the Classical” Ph.d. Dissertation., University of Chicago, 2010, pp. 116.

|

| 20. |

In fact, the disaster, as described by Raghavayya, of performing an on screen dance in this film wearing a female attire prevented any female impersonation on the screen, with exceptions made for those dance sequences which were only meant to evoke humor.

|

| 21. |

The reason behind the name of Kuchipudi annexing to itself that of Bharatanatyam has been explained by historians as one related to currency – Bharatanatyam was popular by the 1930’s, and thus was used by Kuchipudi artists. But, other sources point to the fact that the Kuchipudi artists take the literal meaning of the word Bharatanatyam as ‘dance’. When they name their performance Kuchipudi Bharatanatyam, they mean Kuchipudi ‘dance’ as opposed to Kuchipudi Kalapam/Kuchipudi Yakshaganam etc.

|

| 22. |

Putcha, p 116.

|

| 23. |

Yakshaganam on the theme of Pelli (marriage), in Kannatalli (1953), choreographed and performed by Pasumarthy Krishnamurthy is one such example.

|

| 24. |

Ravi Kondal Rao, (pers. comm., Hyderabad, August, 2013.)

|

| 25. |

Pasumarthy Krishnamurthy in Patala Bhairavi (1951), Vedantam Raghavayya in Rahasyam (1967) being some of them.

|

| 26. |

Gunasundari Katha (), directed by K.V. Reddi is one example.

|

| 27. |

Anjali Pictures was established by Anjali Devi, the actress and her musician husband Adinarayana Rao in 1951. (For details, see Srinivas, 2013.)

|

| 28. |

For example Pelli Chesi Chudu (1952), Jayasimha (1955), Rajanandini (1958), Intiguttu (1958), Dakshayagnam (1962).

|

| 29. |

For example, female courtesan dance traditions including mejuvani performance traditions and temple dance traditions.

|

| 30. |

Nattuvanars were the men who belonged to the traditional dance communities, who doubled as gurus and as cymbal-wielders for performances.

|

| 31. |

Soneji (email correspondence, May, 2014)

|

| 32. |

For details, see Davesh Soneji “Performing Satyabhama: Text, Context, Memory and Mimesis in Telugu-speaking South India,” Ph.d. Diss., McGill University, 2004.

|

| 33. |

Seshu, as he was popularly known in dance circles, was a prime disciple of Vempati Chinna Satyam.

|

| 34. |

Siri siri muvva (1976), Sankarabharanam (1980), Swarna Kamalam (1988) being some of the examples.

|

| 35. |

Singitam Srinivasa Rao (pers. comm.., Chennai, December, 2012).

|

| 36. |

Son of Vedantam Rattayya Sarma, winner of Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar for Kuchipudi, given by SNA, in short, a hereditary Kuchipudi artist.

|

| 37. |

Full name, D.S.V. Sastry, celebrated singer/music composer for Kuchipudi dance today, trained under hereditary Kuchipudi artists in both music and dance.

|

| 38. |

K. Viswanath (pers. comm., Hyderabad, December, 2009.)

|

Katyayani Thota is a research scholar in the Department of Dance, S.N. School of Arts & Communication, University of Hyderabad. She is pursuing her research on the dialogue between Kuchipudi & Telugu cinema, until 1960s. Also a practitioner of Kuchipudi, who has been training in it and performing for the past 10 years, she is a part of the core team of the Lasyakalpa Foundation, a non-profit cultural organisation based in Hyderabad.

Anuradha (Jonnalagadda) Tadakamalla is a Professor of Dance in the Sarojini Naidu School of Arts and Communication, University of Hyderabad. A well known scholar and performer of Kuchipudi, she is deeply engaged in writing and choreography of innovative themes in Kuchipudi.

Courtesy: iqlikmovies.com

Courtesy: en.wikipedia.org

Courtesy: www.thehindu.com

Courtesy: jollyhoo.com/gallery

|

|