Sam Manekshaw and the Military

Reconstruction

Jaidev Raja

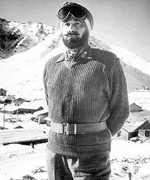

On 16th December 2008, the Indian government issued a stamp to honour the memory of Field Marshal SHFJ (Sam) Manekshaw (1914 – 2008). The portrait on the stamp might be the Indian version of Franz Hals’ “Laughing Cavalier” – the large aquiline nose surmounts a jaunty handlebar moustache and the mouth under it appears about to break into a smile – it is an image of what we would all like a military hero to be.

Small wonder then, that when the TV anchor Karan Thapar interviewed Gohar Ayub Khan of Pakistan and alleged that Sam Manekshaw had been a spy who passed on military plans to Pakistan while he was Director Military Operations in the 1950’s, and that this had helped Pakistan in 1965, the allegation was met with outrage. “We are a country desperately scarce of heroes” lamented one blogger. To treat Sam Bahadur who gave us India’s greatest moment of pride this way is a shame, not just on Gohar Ayub Khan, the son of a general, but on our media which, in the quest for a few TRPs, has given his accusation the oxygen that will help him sell a few hundred copies of his book”.

Small wonder then, that when the TV anchor Karan Thapar interviewed Gohar Ayub Khan of Pakistan and alleged that Sam Manekshaw had been a spy who passed on military plans to Pakistan while he was Director Military Operations in the 1950’s, and that this had helped Pakistan in 1965, the allegation was met with outrage. “We are a country desperately scarce of heroes” lamented one blogger. To treat Sam Bahadur who gave us India’s greatest moment of pride this way is a shame, not just on Gohar Ayub Khan, the son of a general, but on our media which, in the quest for a few TRPs, has given his accusation the oxygen that will help him sell a few hundred copies of his book”."This is not a revelation but an allegation and that too a baseless one. Sam Manekshaw Unless this is proved, it should be dismissed by highest order of contempt," huffed former chief of Army Staff, General Shankar Roy Choudhary.

This allegation can be rejected if only because the doctrine of the Indian army had changed considerably since the early 1950’s – especially following the war with China in 1962. One can only guess at Karan Thapar’s motives in conducting this somewhat dubious interview. Perhaps

the only honourable one, if it can be called that, was to rehabilitate the reputation of his late father General P.N. Thapar.

the only honourable one, if it can be called that, was to rehabilitate the reputation of his late father General P.N. Thapar.The old field marshal, by then on his deathbed, was probably past caring. To a man who had seen several ups and downs in his life – as a young officer he was practically given up for dead- the entire drama must have seemed absurd. Manekshaw (who had joined the army as an act of rebellion against his father who refused to send him abroad for medical training) started his career brilliantly. As a young captain he was wounded twice on the Burma front – once in circumstances of exceptional gallantry which won him the Military Cross. Legend has it that the Divisional Commander, Major General D T Cowan personally pinned the medal on what he then thought was a mortally wounded Manekshaw on the grounds that MCs are not awarded posthumously. General Thapar Yet Manekshaw recovered -thanks to the attentions of an Australian surgeon who chose to operate on him in preference to other more hopeful cases. At the onset of Indian Independence, Manekshaw, now a lieutenant colonel, was the ranking Indian staff officer in the Military Operations Directorate under a British brigadier. In this capacity he was responsible for planning the Indian response to Pakistan’s invasion of Kashmir. When the British brigadier left, it was Manekshaw who filled his shoes. His career seemed headed for the success.

But free India’s leaders were a different breed from warlords of the Second World War. The cultural difference between the Congress, which took over power in India, and the Indian armed forces was seemingly unbridgeable. The congress – pacifist, Gandhian and socialist was led by Nehru, the antifascist, anti imperialist internationalist. The Indian Army on the other hand was officered at the senior level by Indians who had been selected for their ‘non controversial’- that is, apolitical and loyalist – backgrounds. They were initially trained at the Royal Military Academy in Sandhurst and returned to India after a determined effort to eliminate all Índianness from them. “Before the second world war”, writes Neville Maxwell in his book India’s China War, “the Indian officers of the Indian Army, to the last a minority, tended to be as British as the British. Curry was for Sunday lunch, when it would be eaten with a spoon and fork; dinner jackets were mandatory when mess uniform was not worn; to be teetotal was a suspect oddity … and to talk in an Indian language, a gaffe”. “At its best” he adds, “this (tradition) expressed itself in the highest professionalism and zest for soldiering, complemented by an impatience for intrigue and politics – often treated as synonymous”.

Nothing could be more different from the left wing anti-imperialist culture of the Nehruvian Congress. That they functioned at all together in 1948 was a miracle of sorts – perhaps attributable to the fact that the Congress had yet to find its feet. Besides, all over the newly decolonized world, sloppy civilian governments were being replaced by charismatic military men on white horses – the nearest example being neighbouring Pakistan. Although the Indian Armed Forces showed no taste for political interference, it must have seemed to the leaders of newly independent India that the Army, idle in its cantonments, was a dangerous thing to have around. A concerted campaign to bring the Armed Forces under greater civilian control was launched – symbolized by the steady erosion of the position of service chiefs in the government’s order of precedence. The role of the Indian Army was seen as very small in independent India. After all, this was a country with no quarrels with anyone and minor problems like Kashmir or Goa could be met with “mere police action”. This also suited the priorities of the Nehruvian Congress – there were so many other things to spend money on than defence. It was against this background that a purge of the old guard pre independence “British” Indian officers was conducted. The instrument chosen for this transformation was Lt General B M “Biji” Kaul. Kaul’s background should have made him the ideal ‘British Indian” officer –he was a Sandhurst graduate who had been commissioned into an infantry regiment. But early in his career he got himself transferred to the supply and logistics arm – the Army Service Corps - a rather safer assignment. Although he claims that he tried his best at the outbreak of the Second World War to get himself reposted to his old infantry regiment he was unsuccessful – or unwanted. After independence Kaul, though an ASC officer, used his relationship with Nehru (he was a cousin) to get command of an infantry brigade and then an infantry division – a sine qua non for reaching the highest levels of command in the army. This was when the deep divisions within the officer corps became apparent. Like all colonial elites the officer class could not escape a gnawing sense of guilt about their service to the imperial power. During the Second World War their loyalty had been tested by the formation of the Indian National Army from the prisoners of war by the Japanese. After the war, the trials of captured INA soldiers had aroused widespread protests in soon – to – be – independent India. (Although he had spiritedly championed the cause of the INA officers in 1946, Nehru, post independence, had no use for them).Those officers who had remained loyal to the “King Emperor” could therefore be seen as less than ideally patriotic. Further, the expansion of the army during the war had seen a new class of commissioned officer – less loyal, more national minded, bourgeois rather than feudal by background and impatient with the airs of the King’s Commissioned Indian Officers. Kaul soon established himself as the leader of this faction – derisively labelled “Kaul boys” by Manekshaw. Kaul’s rise also coincided with the arrival on the scene of V K Krishna Menon as Defence Minister. It is hard to believe in hindsight the enthusiasm with which Menon’s appointment was initially received by the army. Here, it was felt, was a high profile minister who would end the years of neglect the Army had been subjected to. The army soon found that they had exchanged King Log for King Stork, like the frogs in the legend. Brilliant, notoriously short tempered, not inclined to suffer fools gladly and inclined to regard all army officers as fools anyway, Menon, a Republican sympathizer during the Spanish Civil War, was determined to see to it that no Franco emerged from the Indian Army. In the charismatic General K. S Thimayya, DSO, Chief of Army Staff Menon must have seen exactly such a figure. Friction between the two soon became notorious, and the Menon Thimayya incident .Thimayya submitted his resignation, protesting against Menon’s interference in senior military appointments (specifically the appointment of the unqualified Kaul as Chief of General Staff). The fracas reached the press and Nehru hastily summoned Thimayya to persuade him to withdraw his resignation with assurances that his grievances would be looked into. Later, when questioned about it in Parliament, Nehru humiliatingly put the blame for the incident on Thimayya’s immaturity. His failure to resubmit his resignation at this point considerably reduced Thimayya’s stature in the Army. His recommendation of his one time World War II colleague SPS Thorat as his successor was unceremoniously brushed aside and the now infamous General P N Thapar was appointed as Chief of Army Staff, with Kaul as his effective deputy – the Chief of General Staff. After this there was no doubt about who called the shots in the Indian Army. It can be argued that what Menon wanted to achieve was the transformation of the Army from the old British style force to something along the lines of the People’s Liberation Army of China – an organisation whose potential could be harnessed in peace time for civilian tasks such as public works. This at least is the view of the authors of the official history of the India China War (not published but available on the Internet). If so, he must have seen Kaul as a useful ally. His worst enemies acknowledged that Kaul was an energetic and talented organizer and one of his achievements as GOC 4th Division had been responsible Project Amar – the construction of military barracks using the troops of the division – an unmilitary employment of soldiers frowned upon by the conservative and purist army officers, who regarded Kaul’s rise to high office with increasing alarm.

Kaul justified the alarm. As Chief of General Staff wasted no time in carrying out a purge of all “British Indian”officers – starting with Lt Gen SD Verma, a DSO from World War II whose only fault appears to have been bringing shortages of equipment to the notice of the government – and of course Major General Sam Manekshaw. As Kaul puts it in his memoirs: “Some of our senior army officers were in the habit of making tendentious and indiscreet remarks against our national leaders and extolled the erstwhile British rulers of India……. I came to know of specific cases of antinational and indiscreet utterances – some made in the presence of foreigners – on the part of a few senior officers… and accordingly brought it to the notice of General Thapar”. This was quite plausible – one famous quote attributed to Manekshaw goes as follows:” "I wonder whether those of our political masters who have been put in charge of the defence of the country can distinguish a mortar from a motor, a gun from a howitzer or a guerrilla from a gorilla – though, judging by their behaviour they resemble the latter." By the end of the 1950’s Manekshaw, who had commanded a division with distinction in the north east, had become a marked man. He was now commandant of the Defence Services Staff College in Wellington in the Nilgiris. “Kaul boys” on his staff had been encouraged to report on his words and actions and he did his cause no good by freely providing them with material. A commission of inquiry was instituted to inquire into his conduct. Although the commission found nothing culpable beyond a tendency to put his foot in his mouth, it was clear that Manekshaw would end his career in obscurity.

And then came the Chinese.

The detailed background to the border dispute between China and India is outside the scope of the article. Whatever be the merits on either side, it was apparent by 1960 that the dispute was beyond solution at the negotiating table. This being the case, both sides prepared for a military resolution to the conflict. On the Indian side, this took the shape of the notorious ‘Forward Policy’- setting up posts all along the disputed area and moving them forward often without logistical support. It was a sort of non violent Gandhian military tactic. Nehru had been convinced by his emissary S. Gopal (the President’s son), who had studied the history of the dispute in the British archives, that the Chinese claims to territory were not only false but dishonest. Since moral power was on the Indian side, the Chinese would have no option but to give way, as the British did. Meanwhile details of supply and logistics were merely that – details. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to the Indians that the Chinese may be perfectly sincere in their claim – rightly or wrongly – and that they would be willing to act on their beliefs. An article by A G Noorani in Frontline dated October 24th 2008 shows, with the support of contemporary maps that the demarcation of the Aksai Chin boundary was carried out unilaterally by post independence India without consulting the Chinese.

The fallacious reasoning behind the Forward Policy was encouraged by the then director of intelligence, B N Mallik who consistently encouraged the government in the belief that the Chinese would offer no resistance to Indian forward moves. This directly contradicted Mallik’s own experience – in 1959 a Chinese patrol had ambushed and imprisoned an Indian police party on the Ladakh border. Why then did Mallik encourage the government in its folly? One possible answer is that Mallik’s version of the 1959 incident was wrong – it was not the Chinese who had ambushed the Indian patrol but the other way around. If this was true, one can understand Mallik’s position – if we do not unduly provoke the Chinese they will not attack.

In any case it was felt that the forward policy should be implemented and anyone who stood in its way was to be brushed aside. One such officer was Lt General Umrao Singh, the commander of XXXIII Corps, the formation that was responsible for the defence of the Macmahon line. Matters were not helped by the fact that Umrao Singh and his superior, L P Sen, the GOC in C Eastern Command, and a DSO from the Second World War, cordially hated each other. Umrao flatly refused to move a single unit or formation forward without adequate logistical support.

Sen’s role in this whole affair is a puzzling one. A brilliant officer who besides commanding a batallion in Burma with distinction had also led a brigade in Kashmir soon after independence and written a book about the campaign, Sen was caught between Army HQ’s forward policy and Umrao Singh’s obduracy. Sen decided to ignore the warnings of his subordinate and play up to the wishes of Army HQ. The only explanation for Sen’s behaviousr seems to be this: having seen the fates of his erstwhile colleagues Thimayya and Thorat, Sen realized that there was no profit in antagonising the Kaul faction in the army which was on the ascendant. It was clear that Kaul was being positioned for the highest rank, but he still had to command a corps and a field army (or Command) before qualifying to become Chief of Army Staff. Sen must have calculated that he would fill the gap between Thapar’s retirement and Kaul’s taking over.

Meanwhile what was to be done with Umrao Singh? A straight sacking would not have gone down well with the public, especially after the Thimayya incident. The Army HQ solution was to create a new formation, the IV Corps, which would now be responsible for the defence of the Macmahon Line while Umrao Singh’s XXIII Corps was assigned to other duties. A search was now on for a Corps commander for this new formation. The obvious choice, Sam Manekshaw, languishing in the Staff College at Wellington was rejected out of hand. Kaul therefore decided to step down to glory as it were and take over command of IV Corps himself. If he could successfully pull off a victory, all jibes by decorated World War II veterans about his lack of combat experience would have been silenced permanently. Kaul incidentally lost no time in informing the press of this appointment and this formation of a task force with the “deputy commander in chief” as its head was seized upon by the Chinese as evidence of Indian belligerence.

Kaul’s incompetent conduct of the operations against the Chinese has been too well documented to need a detailed analysis here. After the initial Chinese thrust, which destroyed Brigadier Dalvi’s ill-fated 7 Brigade, and the subsequent capture of Tawang, a hurried conference was held in Delhi to decide on where the next stand should be made. Thapar, finally summoning up some courage suggested that it should be done at Bomdi La near the foothills. This was clearly not politically

acceptable and Menon is reported to have squelched him with the sarcastic query: “General, why not Bangalore?” It was decided that Se La, a mountain pass halfway up to the Macmahon line would be where a stand would be made. In the event, this political rather than military fortress was swiftly outflanked by the Chinese.

acceptable and Menon is reported to have squelched him with the sarcastic query: “General, why not Bangalore?” It was decided that Se La, a mountain pass halfway up to the Macmahon line would be where a stand would be made. In the event, this political rather than military fortress was swiftly outflanked by the Chinese.Reflecting on this in later years, Thapar ruefully observed that he should have resigned as soon as his recommendations were rejected. In fairness to him it must be said that he had constantly drawn attention to the army’s state of unpreparedness, only to be brushed aside by Nehru, V K Krishna Menon who on the eve of the Chinese aggression assured parliament that ‘never before have our armed forces been better prepared or in finer fettle’.

Kaul had by now been evacuated to Delhi with high altitude sickness acquired during his forays up the mountains to put some steel into his bellyaching commanders (as he saw it), and Sen had decided that he had placated Army HQ long enough. He suggested the name of Sam Manekshaw as Commander IV Corps to replace Kaul at which point, according to him, “Menon hit the roof”. A compromise candidate was agreed upon in the shape of Lt General Harbaksh Singh (who would later successfully lead Western Command against Pakistan in 1965). No sooner had General Harbaksh taken over command than Kaul pronounced himself cured and was reappointed in General Harbaksh’s place over the heated protests of General Sen. It was felt that he “had to be rehabilitated”, in the words of Menon. This wish was not to be fulfilled – the Chinese cut through Indian positions like a knife through butter till they reached the plains, threatening the town of Tezpur.

By now the nation had had enough of Nehru’s, Menon’s and Kaul’s mishandling of the war. Nehru himself continued in office, but Menon was forced to resign as defence minister. Kaul submitted his resignation, and his place in IV Corps was taken by the man whose career he sought to destroy – Sam Manekshaw. It is said that on taking over command, Manekshaw called all his officers into a conference room, strode in, said, “Gentlemen, there will be no more withdrawals”, and strode out. There was, of course nothing to withdraw and nowhere to withdraw to – IV Corps was little more than its headquarters, and though the Government attempted to shore it up with more ill equipped and unacclamatised troops, they were spared further humiliation by the unilateral declaration of ceasefire by the Chinese.

What might Manekshaw’s fate have been if he had taken over command of IV or XXXIII Corps at an earlier stage? It is likely he would have done exactly what Umrao Singh did – and vanished into obscurity like Umrao Singh. On such twists of fate do military reputations hang. Manekshaw was a very cautious planner who in 1971 refused to be bullied into premature action by the political leadership– which, chastened by the lessons of 1962, allowed him to have his way. The initial plan for the Bangladesh sector was to sieze a limited amount of territory to rehabilitate the millions of refugees fleeing Pakistani persecution. The subsequent blitzkrieg like campaign which developed in Bangladesh was a result of local commanders seizing opportunities as and when they occurred with admirable flexibility.

Manekshaw’s post war career was rather less than distinguished. The civilian leadership seems to have regarded this charismatic field marshal with some suspicion and a chance flippant remark made to a foreign newspaper was seized upon to publicly humiliate him. He was never given a prestigious appointment in the government as his predecessors and successors were, and even his back pay as field marshal dating to 1973 was released to him only in April 2007!

Military reputation is not always a matter of ability, but is almost equally dependant on luck. “Is he fortunate?” is what Frederick the Great is supposed to have asked before appointing anybody to command. The fate of Lt General Harbaksh Singh, Manekshaw’s contemporary and rival, is a case in point. Harbaksh Singh was equally a decorated military commander who had commanded a battalion and a brigade in Kashmir in 1948 and a Corps during the China operations. In 1965 he had brilliantly led Western Command against Pakistan. He also had the recommendation of the outgoing Chief of Army Staff, General P.P. Kumaramangalam to be his successor. It would seem that, other things being equal, one would choose the more successful of two army

Military reputation is not always a matter of ability, but is almost equally dependant on luck. “Is he fortunate?” is what Frederick the Great is supposed to have asked before appointing anybody to command. The fate of Lt General Harbaksh Singh, Manekshaw’s contemporary and rival, is a case in point. Harbaksh Singh was equally a decorated military commander who had commanded a battalion and a brigade in Kashmir in 1948 and a Corps during the China operations. In 1965 he had brilliantly led Western Command against Pakistan. He also had the recommendation of the outgoing Chief of Army Staff, General P.P. Kumaramangalam to be his successor. It would seem that, other things being equal, one would choose the more successful of two army Lt General Harbakhsh Singh commanders to be the next chief of army staff. That General Harbaksh was not one to be bullied easily by his superiors is demonstrated in the stand he took against General J N Chaudhuri in 1965 when General Chaudhuri is said to have asked him to evacuate certain areas of Punjab. Nevertheless, it was Manekshaw who was selected and will be remembered as India’s greatest soldier. Perhaps the card that fate holds up its sleeve trumps all the hands that men may play.

List of major sources

Neville Maxwell, India's China War, London: Jonathan Cape, 1970

J P Dalvi, Himalayan Blunder, New Delhi: Natraj Publishers, 2003

Official History of the 1962 War.

See http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/LAND-FORCES/Army/History/1962War/

Kuldip Nayar, India: The Critical Years, New Delhi: Vikas, 1971.

Noorani A G, Maps and Borders, Frontline October 24th 2008

Jaidev Raja is a retired army officer, a writer and a quiz aficionado. He was first runner-up at the second Mastermind India.

Courtesy: sharmajee

Courtesy: indianetzone

Courtesy: hindu

Courtesy: bharat-rakshak