Multicultural Fiction: Degrees of Disaffection

A Trajectory through Nadeem Aslam’s Maps for Lost Lovers, Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake and Zadie Smith’s On Beauty

KR Usha

I

While the modern nation states of the West are still struggling to accommodate the aspirations of their immigrant minorities in their liberal democratic holds, their literary establishments have long given in, celebrating, on the contrary, the shot in the arm that diasporic and ‘ethnic’ writing has given their anaemic literatures. Celebrating this ‘frontierless kind of writing’ as ‘World Fiction’, more than a decade ago, in his essay in Time Pico Iyer (1) lauded the ‘new transcultural writers’ as ‘products … of the international culture that has grown up since the War, (who) are addressing an audience as mixed up, and eclectic and uprooted as themselves.’ If the Booker is the sceptre of the Western establishment, Iyer fairly crows that the ‘Queen’s English has become’ her former ‘subjects’ playground’ and counts off on his fingers the number of writers from her former colonies who have been awarded the coveted literary prize – in the eleven years since Rushdie won the Booker in 1981, (Iyer’s essay was written in 1993) it has been given to ‘two Australians, a part Maori, a South African, a woman of Polish descent, a Nigerian and an exile from Japan.’ To this list we may add two Indians – Arundhati Roy in 1997 and very recently, Kiran Desai in 2006.

To traverse briefly the political and social ground that fertilised the multicultural ethos, in the progressively ‘borderless’ post-war world, with the migration of people from the former colonies to their colonising ‘mothers’ in Europe, or to the new worlds of North America and even Australia, it would seem inevitable that the ‘guests’ would require and demand the conditions and rights necessary for them to function as equal citizens and that the ‘hosts’ would find their philosophies, practices and institutions of governance stretched in different ways as they made the effort to provide these conditions. It was under this rubric that multiculturalism was born and it blossomed.

The multiculturalist position (2) holds that granting all individuals equal citizenship rights and providing access to institutions that would enable them to participate in public life, is not quite enough for them to function fully as human beings. For human beings are born in a cultural context with its specific mores, its own systems of meaning and emphasis from which they acquire their first sense of self and through the mediation of which they learn to understand and negotiate with the world around them. Each of these cultures has its own vision of the good life and provides to its members a sense of bonding and solidarity and deep contentment. For modern liberal democracies to function healthily they must reflect and respect the diversity in their societies in which different communities participate in the public life as equal partners while maintaining their cultural distinctiveness. The state must recognise that an individual’s sense of self-worth is embedded in the collective identity of the larger community of which s/he is a part. For even while providing for the participation of all communities in the public life, there are subtle ways in which it can be thwarted, such as pressure to become part of the ‘mainstream’ or a subtle undermining of minority cultures and values. An enlightened state would demonstrate its intentions through equal opportunity programmes, anti-discrimination laws, affirmative action, group rights for minorities, support for educational and cultural institutions and culturally differentiated applications of laws and policies.

Canada was the first Western nation to officially include multiculturalism in its policy and from the 1970s onwards, multiculturalism became an active policy concern in Australia, the US, the UK, Germany and even Republican France did not stay immune to its influence. In the US, a nation made by immigrant pioneers the liberal modern concept of the ‘melting pot’ where European and African immigrants and native Indians were continuously assimilated into the American brew/stew gave way to the post-modern ‘salad bowl’ with each constituent community maintaining, marking and promoting its distinctiveness.

Post-war multiculturalism, with its faith in cultural distinctiveness, in identity politics and belief that no one community or philosophy could claim to know the best or the whole truth, began as a counterpoint to the homogenising worldview of the seventeenth and eighteenth century Enlightenment Europe with its privileging of reason, the steady application of which would lead to the betterment of humanity, the belief in a natural law that governed man and matter as against theological explanations for the universe, and a liberal humanitarianism – a concern for the individual (3). This translated into social reform in Europe, into belief in common emancipatory goals for all mankind, an aspiring towards common institutions, forms of governance and laws and an ideal vision of the good life. However, it was this spirit that in part filled Vasco da Gama’s adventurous sails and put the steel in Robert Clive’s imperialist spine as they set out to seek their fortunes in the East; a spirit that spurred the colonising nations of Europe into ‘civilising the savages’, ‘reforming’ their societies, institutions and practices in keeping with a universal (Western) ideal, rendering by implication the ‘native’ ways of life, practices and faiths inferior and discardable. (In literature, even the most well-meaning of writers tended to patronise the natives – Rudyard Kipling’s Kim for example, or the works of Joseph Conrad.) For the multiculturalists the avowed Enlightenment belief in the equality of humans, in universalism, faith in ‘reason’ to fashion universal institutions, modes and codes, a ‘one size fits all’ philosophy, liberal and humanist though it may be is another way of ensuring Western domination and undermining ‘Oriental’ lack of worth. This they counter with their belief in the cultural embeddedness of people, that difference and not commonality or universalism is the operational dynamics between people, and that the belief in equality should translate into equal respect for all cultures/groups that comprise society and workable means to publicly affirm and action this respect.

With the increasing complexity of societies, and degrees of difference of multicultural thinking emerging, its two main streams would be the liberal modernist, close to the liberal Enlightenment view of pluralism and the ‘critical, insurgent, postmodernist’ (4), the former setting out to manage cultural diversity within the nation state and the postmodernist positioning itself outside or across national boundaries.

However, critics of multiculturalism argue that it has not succeeded both at the level of political policy and as cultural practice. Multiculturalism, despite its avowed faith in the openness, the self-critical and self-reflective dimension of cultures encourages static, bounded and romantic notions of culture and identity, the glossing over of individual rights in its anxiety to privilege the group, the continuation of traditional inequalities such as gender- and caste-related practices, and a denial of change and progress. At best it encourages a sullen tolerance between groups and not the open, critical dialogue that multiculturalists hope will drive society, that rather than participating in the forging of a new polity, communities lead parallel lives with their diasporic loyalties/ ties growing stronger. Multiculturalism, its critics point out, when seen in context, is the product of the developments of the post-war world – the collapse of the Left, in particular the USSR and the bi-polar world order with the mono-cultural nation state also proving unworkable, the end of liberation movements in the third world based on common guiding/inspiring principles, once its countries had won independence from their imperial rulers and social movements running to the ground in the West: in fact, it is the product of post-war disillusionment, a recognition that inequalities cannot be redressed, that societies cannot be transformed through economic and political reconstruction and hence it is best to accept society as it is and celebrate diversity (5).

There is the strong suggestion that ‘multiculturalism’ is no longer adequate to explain the complex diversities of societies or to deal with them, that we must think of other ways forward or that it will have to re-invent itself or re-define its position, perhaps slice and dice the modern liberal-postmodern distinction further.

II

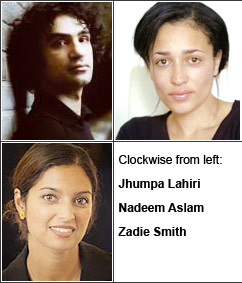

After a broad consideration of the political debates and the cultural co-ordinates of multiculturalism, we now look at how diasporic/ multicultural writing/ World Fiction explores and reflects upon its conditions and what the springs of its imagination are. What are the stories it tells? What are the transactions that take place in the cross over between the narrator and the tale? Three novels by three writers poised on different points on the multicultural spectrum have been

chosen to reflect upon the literary concerns of multicultural writing – Maps for Lost Lovers by Nadeem Aslam, The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri, both published in 2004, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith, published 2005. Of the common features of the writers of World Fiction, Pico Iyer singles out that they are born after the War, are not of Anglo-Saxon ancestry and have chosen to write in English (6) – which would apply to the three writers under consideration, except that Smith is partly of Anglo-Saxon ancestry. Our writers are not yet forty – Aslam and Lahiri perhaps just, and Smith was born in 1975. Aslam, born in Pakistan, left for England when he was fourteen, with his family when his father, a member of the Communist Party had to flee the Zia regime (7); Lahiri was born in England to Bengali Indian parents, was brought up in Rhode Island in the US, and by her own admission is closely bound to her family and Bengali culture. ‘I know’, Lahiri says, ‘that if my parents had stayed in India they would have led a perfectly fine life, they wouldn't have suffered. In many ways they would have been happier … they didn't have to come here for their very existence, their survival. They were here for the sake of greater opportunities, perhaps a better standard of living’. (8); Zadie Smith is a second-generation migrant writer – child of a white, working class British father and a black, immigrant, Jamaican mother (9). The perceived cultural positioning of these three writers in the societies from which they write, Aslam – an immigrant from a politically restrictive environment with a formative religious/cultural identity, transported across the oceans and cast into one of supposedly unrestricted political and personal freedom, Lahiri, an ‘economic escapee’ with strong cultural roots and Zadie Smith, once removed from the mixed-race, mixed-colour background of her parents but an inheritor of their world all the same, having to reap what they have sown, informs their work willy-nilly, particularly the novels under consideration here. It may also not just be incidental that the writers and their works are much lauded and celebrated by readers, critics and the establishment alike. Aslam’s first novel, Season of the Rainbirds, won the Betty Trask Award and Lahiri’s first collection of short stories Interpreter of Maladies, won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2000, ‘for distinguished fiction by an American author … dealing with American life’ putting the author firmly within the literary mainstream, despite some of the stories privileging the perspectives of Indians. (10), Both Maps and The Namesake were on the Booker longlist, and Maps won the Kiriyama Prize for 2005; Smith, celebrated almost with feverish relief by the British literary establishment as much for her ‘British’ credentials as for her writing, is the author of three acclaimed novels – On Beauty went on to win the Orange in 2006.

chosen to reflect upon the literary concerns of multicultural writing – Maps for Lost Lovers by Nadeem Aslam, The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri, both published in 2004, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith, published 2005. Of the common features of the writers of World Fiction, Pico Iyer singles out that they are born after the War, are not of Anglo-Saxon ancestry and have chosen to write in English (6) – which would apply to the three writers under consideration, except that Smith is partly of Anglo-Saxon ancestry. Our writers are not yet forty – Aslam and Lahiri perhaps just, and Smith was born in 1975. Aslam, born in Pakistan, left for England when he was fourteen, with his family when his father, a member of the Communist Party had to flee the Zia regime (7); Lahiri was born in England to Bengali Indian parents, was brought up in Rhode Island in the US, and by her own admission is closely bound to her family and Bengali culture. ‘I know’, Lahiri says, ‘that if my parents had stayed in India they would have led a perfectly fine life, they wouldn't have suffered. In many ways they would have been happier … they didn't have to come here for their very existence, their survival. They were here for the sake of greater opportunities, perhaps a better standard of living’. (8); Zadie Smith is a second-generation migrant writer – child of a white, working class British father and a black, immigrant, Jamaican mother (9). The perceived cultural positioning of these three writers in the societies from which they write, Aslam – an immigrant from a politically restrictive environment with a formative religious/cultural identity, transported across the oceans and cast into one of supposedly unrestricted political and personal freedom, Lahiri, an ‘economic escapee’ with strong cultural roots and Zadie Smith, once removed from the mixed-race, mixed-colour background of her parents but an inheritor of their world all the same, having to reap what they have sown, informs their work willy-nilly, particularly the novels under consideration here. It may also not just be incidental that the writers and their works are much lauded and celebrated by readers, critics and the establishment alike. Aslam’s first novel, Season of the Rainbirds, won the Betty Trask Award and Lahiri’s first collection of short stories Interpreter of Maladies, won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2000, ‘for distinguished fiction by an American author … dealing with American life’ putting the author firmly within the literary mainstream, despite some of the stories privileging the perspectives of Indians. (10), Both Maps and The Namesake were on the Booker longlist, and Maps won the Kiriyama Prize for 2005; Smith, celebrated almost with feverish relief by the British literary establishment as much for her ‘British’ credentials as for her writing, is the author of three acclaimed novels – On Beauty went on to win the Orange in 2006.Multicultural writing is included under the umbrella of post-colonial writing and reflects many of its dominant themes – a concern with place and displacement, the consequences of dislocation including the linguistic alienation so produced (‘the plight of those torn between mother lands and mother tongues’ as Pico Iyer puts it), the crisis of identity (11), the experience of technically being an insider but being a de facto outsider in the new world and the sense of loss, incomprehension and powerlessness that results. The writers of the diaspora often bring with them the flavours of other languages, their storytelling traditions, their myths and their ways of seeing in devising new narrative modes, ‘using their limnal position not just as a theme but as an instrument’ (Pico Iyer). Reflecting on how the writing of literature and the readership for it have changed, multicultural writers, Iyer notes, who were studied in anthropology or sociology courses are now admitted into the syllabus of English literature. Needless to say, the three novels under consideration reflect the themes mentioned above in varying degrees of consciousness and detail. But the point is not so much in the themes reflected but in how they vary depending upon the background and experiences of the characters, which in turn is influenced by where their authors are coming from.

III

In Maps for Lost Lovers, echoing the circumstances of Aslam’s own family, which saw his bohemian Communist-poet-film maker father reduced to a factory worker cum garbage collector (12), Shamas and his wife Kaukab move from Pakistan to England with their children. Shamas, a poet and a Communist has had to leave Pakistan to avoid persecution from Zia’s military regime. His wife Kaukab, traditional, conservative, ‘the daughter of a cleric, born and raised in the shadow of a minaret’ (13), is the main vehicle through which Aslam works out his central concerns – of an immigrant community, nurtured on very clear visions of the good and the bad, the right and the wrong, the acceptable and the unacceptable, being uprooted and transplanted in hostile soil, where every norm and more, even the very air conflicts with their own. There can be no compromise here as there is no common ground.

In Maps for Lost Lovers, echoing the circumstances of Aslam’s own family, which saw his bohemian Communist-poet-film maker father reduced to a factory worker cum garbage collector (12), Shamas and his wife Kaukab move from Pakistan to England with their children. Shamas, a poet and a Communist has had to leave Pakistan to avoid persecution from Zia’s military regime. His wife Kaukab, traditional, conservative, ‘the daughter of a cleric, born and raised in the shadow of a minaret’ (13), is the main vehicle through which Aslam works out his central concerns – of an immigrant community, nurtured on very clear visions of the good and the bad, the right and the wrong, the acceptable and the unacceptable, being uprooted and transplanted in hostile soil, where every norm and more, even the very air conflicts with their own. There can be no compromise here as there is no common ground.From Sohni Dharti (Golden Earth) in Pakistan, Shamas and Kaukab end up in Dasht-e-Tanhai – ‘the Wilderness of Solitude’ or ‘the Desert of Loneliness’ – a beautiful hamlet somewhere in England, set amidst a beautiful lake, which Aslam magically and true to the convention of diasporic writers recreating the flora and the fauna and the feel of the lost land, populates with non-native peacocks, moths, parakeets and fireflies but which is a dead-end all the same. All successful whites, Indians and Pakistanis have long moved out of there, only the ‘losers’, the illegal immigrants and the idealists like Shamas who still believe that ‘a fairer, more just way of organising the world has to be found’, are left. Even as she pines for Sohni Dharti, Kaukab knows that she will never leave this desolation because her children are here.

Kaukab is a good woman, who wishes no one ill and harms no one, who lives by her faith and draws her strength from it believing --‘Islam has said that in order not to be unworthy of being, only one thing was required: love’, and yet in growing her family, she alienates her husband and children completely. Her children believe that she has destroyed them, and she cannot understand why they, ‘the other half of her heartbeat’ have turned against her. Kaukab’s children, almost vengefully, have defined themselves in diametrical opposition to and extreme anger against their mother, to all that she believes is good and holy. Even as Kaukab swears by love, everywhere it is the transgressively sexual that rears its head, inspired by the ‘immoral and decadent (Western) civilisation … intent on soiling what was pure and transcendental about human existence’. Charag, the eldest, wants to be an artist but is forced to study medicine -- for who would want to marry an artist’s sister, till he rebels, not just going on to become an artist but even marrying a white woman – the thing that his mother and all the mothers in Dasht-e-Tanhai live in dread of. On a rare visit home, Charag unveils an acclaimed painting of his -- a nude self-portrait that his mother averts her face from, not before noticing its uncircumcised penis. ‘Why must you mock my sentiments and our religion like this?’ she asks and her son cannot make her understand that it is a metaphor, an attempt ‘to break away from all the bonds and ties that manipulative groups have thought up for their own advantage’. When her younger son Ujala turns argumentative upon entering his teens, she goes to the cleric in the local mosque for help, who recommends a compliant-making ‘salt’ to put into his food – when Ujala finds out that it is a bromide that is usually put into prisoners’ food to lower their libido, he leaves home. ‘She won’t allow reason to enter this house’, he says and if one were not so sure that the author sees Kaukab as the moral force of the novel, one would accuse him of casting her as the Oriental savage. Mah-jabin, her daughter feels that he mother has failed her most crucially – instead of constraining her, she allows Mah-jabin at sixteen to go to Pakistan and marry a cousin she has never seen before. The man is a boor; the marriage fails and Mah-jabin returns to England but lives away from her parents. Her girlish, sisterly exchanges with her mother become a thing of the past, she is guarded in her conversation now, ‘afraid of sounding casual about her new familiarities’ but despite her care, they come to blows with Mah-jabin accusing her mother of taking a knife to her.

When Ujala walks into the house after a seven-year absence, weeping Kaukab wraps her arms around him ‘opening her hands wide to touch as much of his back as possible’, but she backs off quickly for she remembers someone telling her about the latest Western theories … that all mothers secretly want to go to bed with their sons. Kaukab is repulsed: ‘these kinds of things were said by vulgar hawkers and fishwives in the bazaars of Pakistan but here in England educated people said them on television.’ Kaukab is scared even to be demonstrative in her affection for her little grandson ‘in case the whites have come up with a theory about grandmothers and grandsons too.’ In gaining an untrammelled freedom in a more knowing world, they, the people from a more ignorant and restrictive land, have lost their innocence; the new free world has its own rules and notions, which are warped and perverted in their own way, and of which they are yet to learn.

England is so bewilderingly alien that ‘even things spoke a different language … the heart said “boom boom” instead of “dhak dhak”, a gun said “bang” instead of “thah”; things fell with a “thud”, not a “dharam” …’ Kaukab and the other women from the subcontinent have so little contact with the white English that when one of them has to make an emergency call, she wonders whether to add ‘fuck’ to her speech now and then to sound more authentic. The way the women of Dasht-e-Tanhai control their children is by threatening them with white people. Kaukab would like to talk more to others, especially her white daughter-in-law whom she grows to like and whose good opinion she wants, but is afraid her English will let her down. So completely robbed of her self-esteem is Kaukab that every time she speaks to Stella she surreptitiously blows into the hollow of her hand to make sure her breath is not stale. But still, the women of Dasht-e-Tanhai sympathise with the British queen for the way her children are humiliating her.

Kaukab is only too aware of her increasing marginalisation; she feels ‘utterly empty all the time’ and acknowledges that she ‘cannot seem to move without bruising anyone’ and that she doesn’t mean to cause pain. If Kaukab is bereft of love, her husband Shamas too is seeking it in his own way (the quest for love being one of the themes of the novel) and he supports his wife half-heartedly in all her decisions because he sees her as a ‘poor immigrant woman in a hostile white environment’.

There are other characters, other stories than this family in Maps but they work as devices to show up the violent contradictions in immigrant communities, their refusal to countenance any defiance, any departure from the norm – this often being their line of defence against a hostile opposing force. The lovers of the title are Jugnu, Shamas’s brother and Chanda, who are living together without getting married, as Chanda cannot get a divorce from her absconding second husband. The events in the novel are set astir when the two go missing. People suspect that Chanda’s brothers have killed them to save the family honour and Dasht-e-Tanhai cannot understand why the English consider it a crime. Then there is Suraya, who like Mah-jabin and Chanda marries a man in Pakistan (in Aslam’s world, the women brought up in England are beautiful, spirited and intelligent but they give in to tradition, while the men they marry in Pakistan are all rough, hairy brutes), is divorced by him in a drunken rage and now is back in Dasht-e-Tanhai to try and get a man to marry and divorce her quickly for that is an Islamic norm she has to satisfy before re-marrying her original husband and getting back to her beloved son. Suraya tries her luck first with Charag, who is appalled by her clumsy attempts to ‘catch’ him, but she finds his father easy meat – he is, after all, ripe for love.

One of the triumphs of multicultural writing, as celebrated by Pico Iyer among others, is its ability to carry with it the colours of its native landscape, the cadences of its language, the polyphony of its voices and its unique metaphor. Aslam’s prose, in that sense, is distinctly un-English; it resounds with the lush imagery of Urdu/Punjabi, of any subcontinental bhasha for that matter, the richness of its sounds and its ways of seeing. There are quotations from Ghalib, Munir Niazi and Mir Taqui Mir; Shamas’s bookshop apart from Urdu poets also stocks Kalidasa, there is a reference to the Shiva-Parvati love legend and the Koranic version of the fall of man. Jugnu, the lepidopterist to whom butterflies and peacocks (apart from children and women) flock is projected as the embodiment of eternal, formless, ‘nirguna’ love, like Krishna.

The stem of a Madonna lily has ‘a sparrow-foot like division at the top bearing the hollow, coffin-shaped buds and the already open heavy blooms, white as the flesh of a newly-split coconut’; the patterns on a Cinnabar moth are like the ‘printed kameez, plain salwar of subcontinental women; a rustling newspaper sounds like a peacock dancing with its tail fanned out, the feathers aquiver’. A woman’s lover, visiting from the subcontinent brings her ‘the five arrows of Love’ – a red lotus, a deep-red asoka flower, coral-green mango blossom, yellow jasmine and a blue lily. The stars and constellations in the dark are ‘the dust raised by Muhammad’s winged mount as it carried him to the heavens for an audience with Allah on his Night journey’. Hindi film regulars can also imagine the original that inspired, ‘From this existence of two moments, we have to steal a life.’

In Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake, Ashima and Ashoke Ganguli move to the US after their marriage, where Ashoke is a student working on his doctorate in electrical engineering at MIT. The novel is the space in which Ashima settles down as bride and mother and her son Gogol grows up as a citizen of the new world. Lahiri says of her book -- ‘While the Namesake is not explicitly autobiographical, it sticks pretty closely to the general way I was raised … The terrain is very much the terrain of my own life – new England and New York with Calcutta always hovering in the background’ (14).

In Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake, Ashima and Ashoke Ganguli move to the US after their marriage, where Ashoke is a student working on his doctorate in electrical engineering at MIT. The novel is the space in which Ashima settles down as bride and mother and her son Gogol grows up as a citizen of the new world. Lahiri says of her book -- ‘While the Namesake is not explicitly autobiographical, it sticks pretty closely to the general way I was raised … The terrain is very much the terrain of my own life – new England and New York with Calcutta always hovering in the background’ (14).Ashima and Ashoke’s is an ‘arranged’ marriage; true to her unstated mores Ashima does not call her husband by his name or even think of it when she thinks of him. The only moment of whimsical intimacy that occurs before (or even after) their marriage is when Ashima impulsively steps into Ashoke’s still-warm shoes, that he has taken off in the corridor when he comes to ‘see’ her in her parents’ Calcutta home – ‘lingering sweat of the owner’s feet mingled with hers, causing her heart to race; it was the closest thing she had ever experienced to the touch of a man’ (15). There will be no celebrations of birthdays and anniversaries, and much later their son, on seeing an American friend’s parents casually relaxing against each other on a settee realises that he hasn’t seen a single moment of physical affection between his parents, and yet Ashima does not doubt her husband’s love, their mutual love for each other.

Even as she settles in, far from home, in frigid New England, Ashima sees America as ‘leafless trees with ice-covered branches. Dog urine and excrement embedded in snowbanks. Not a soul on the street.’ She makes up by re-reading the letters and Bengali magazines from home and the events in their lives, their griefs and joys, deaths and marriages are more real to her.

If Kaukab is violently uprooted, Ashima is disgruntledly displaced. Being a foreigner, she realises, ‘is a sort of lifelong pregnancy – a perpetual wait, a constant burden, a continuous feeling out of sorts. It is an ongoing responsibility, a parenthesis in what had once been ordinary life, only to discover that that previous life has vanished, replaced by something more complicated and demanding. Like pregnancy, being a foreigner, Ashima believes, elicits the same curiosity from strangers, the same combination of pity and respect’. So even while America is a continuous assault on her sensibilities, it is not quite the canker that eats into her soul and life. Ashima is horrified when her son’s school takes his class to a cemetery to make rubbings of gravestones as part of an art project – What next, she wants to know, a trip to the morgue? – but she would not think of forbidding it, and when in hospital to have a baby, and the hospital gown only reaches her knees instead of covering her legs completely, it only causes her ‘mild embarrassment’. But to Kaukab, her white daughter-in-law’s bare legs are a sign of moral degradation and mischievous intent. The Ganguli’s encounters with racism too are much milder, the only overt instance being when the ‘guli’ on their nameplate is changed to ‘green’ so that the name reads ‘Gangreen’, an incident that Ashoke dismisses as a boyish prank.

So Ashima learns, under the circumstances, to make do with substitutes. Rice Krispies and Planters Peanuts without mustard oil go into her jhalmuri – ‘a humble approximation of the snack sold for pennies on Calcutta sidewalks and on railway platforms throughout India, spilling from newspaper cones’, and she announces that it is possible to make halwa from Cream of Wheat. Instead of family, she makes do with their extended circle of Bengali friends, but with the knowledge that her children are bereft of something very vital. When her son is born without ‘a single grandparent or parent or uncle or aunt at her side, the baby’s birth, like most everything else in America, feels somehow haphazard, only half true. … she can’t help but pity him. She has never known of a person entering the world so alone, so deprived.’ And surely enough, at her son’s annaprasan ceremony it is not her brother but a friend who feeds him his first rice.

Gradually, for the sake of their children, Ashoke and Ashima give in. Even if it unsettles them that their children sound just like Americans, conversing in a language that still confounds them and ‘in accents they are accustomed not to trust’. Ashima makes roast beef sandwiches for them, starts celebrating Christmas which her children look forward to more than the Durga and Saraswati puja celebrations with their fellow Bengalis, and the finality of their acceptance is signalled when Ashoke, waiting in line at the airport on a trip to Calcutta, produces two Indian and two US passports and says, ‘Four in the family … Two Hindu meals, please.’

It is with Gogol, Ashima’s son that the clash with America becomes sharper and more nuanced for Gogol, unlike his mother has not the comfort of coming to an alien place, fully formed. To him, the alien place is his home, his natural environment. He does not think of India as ‘desh’ but like all Americans, as India.

The framework of Aslam’s and Lahiri’s novels (and Smith’s too if one were to consider it more broadly in terms of a family’s continental migration, and their coming to terms with their identity) is the same; they speak of the same struggles and quests. With Aslam, the clash between the cultures is so violent and visceral that the next generation turns its parents’ gold into straw; the children of migrants identify themselves in virulent opposition to their parents, a process that is lacking in grace, and far from being an implicit, restful accumulation of the self, is a retaliatory, cancerous growth. In The Namesake, the struggle is attenuated, not as sharply accentuated, less a violent clash with the external environment than a struggle that has to be resolved from within. The religious and cultural restrictions placed on the Ganguli children are not oppressive, just mildly restricting, irrelevant and boring. Given this, it would seem obvious that the contradictions of identity would be less knotty and easier to resolve, that the struggle would not be so deep and all-encompassing. Lahiri suggests otherwise. Of her character and herself Lahiri admits, ‘Neither Gogol nor I was terribly rebellious … But even ordinary things felt like a rebellion from my upbringing -- what I ate, what I listened to, whom I befriended, what I read. Things my American friends' parents wouldn't think to remark upon were always remarked upon by mine.’ (16)

Gogol, the ‘namesake’ of the directly telling title, is named after the Russian writer Nikolai Gogol, whom his father admires. But as per the Bengali habit Gogol is his pet name or daknaam and he is given a formal ‘good’ name, ‘Nikhil’ (Perhaps, the Indian ‘What is your good name?’ can be traced to this). Much like what happened with Lahiri herself when ‘Jhumpa’ became her ‘good’ name, when Gogol is enrolled into school, he refuses to respond to ‘Nikhil’ and Gogol becomes his ‘good’ name – a name that he grows to hate, considering it ‘ludicrous … lacking in gravity and dignity ‘ and above all irrelevant, and proceeds to live down and finally discard.

Initially, the name is mildly annoying, much like the Bengali classes he is made to attend and ‘taught to write letters that hang from a bar’, or having to learn about the Bengali Renaissance and the exploits of a distant Subhash Chandra Bose on a precious Saturday morning, when he’d rather be in his drawing class, or like putting up with the discomforts of a visit to Calcutta where he sleeps under a mosquito net and bathes by pouring tin cups of water over his head. But when he turns eighteen, before his freshman year at Yale is about to begin, Gogol goes to the Family Court on his own and formally changes his name to ‘Nikhil’ which means ‘he who is entire – encompassing all’.

As Nikhil he finds it ‘easier to ignore his parents, to tune out of their concerns and pleas’, grow a goatee, smoke Camel Lights, get a fake ID that allows him to be served liquor and lose his virginity one night at a party with a girl who has vanished from the room when he wakes up and whose name he cannot remember. In his first semester at Yale ‘obediently and unwillingly’ he goes home on weekends, impatient to get back, inadvertently referring to his room in Yale as ‘home’ and outraging his mother. When he acquires his first girlfriend he does not tell his parents about her, having ‘no patience for their surprise, their nervousness, their quiet disappointment, their questions about what Ruth’s parents did and whether or not the relationship was serious.’ When they finally come to know about Ruth they express no curiosity about her – ‘His relationship with her is one accomplishment in his life about which they are not in the least bit proud or pleased.’ When Ruth goes away to Oxford he ‘longs for her as his parents have longed, all these years, for the people they love in India – for the first time in his life, he knows this feeling.’ After Yale, deliberately and to his parents’ distress, he chooses Columbia to do architecture and not MIT, his father’s alma mater, for he does not want to move back to Massachusetts, the city his parents have lived in, to go back to ‘pujos and Bengali parties, to remain unquestionably in their world’.

With his next relationship, now as an architect living in New York, he is completely claimed by America and like a foetus lolling in amniotic fluid he offers no resistance, he wants to remain cocooned -- till inevitably the waters break. Maxine – moneyed, confident, with an old world certainty, captures his attention. He is seduced by her house, her parents, their lifestyle, their dog and their food. He moves in with Maxine and her parents and is given his own set of keys to the house.

The contrast between Maxine’s parents and his own cannot be more marked or more damning. At the dinner table the Ratliffs have vociferous opinionated conversations about things his parents don’t care about – ‘movies, exhibits at museums, good restaurants, the design of everyday things …Gogol is unaccustomed to this sort of talk at mealtimes, to the indulgent ritual of the lingering meal, and the pleasant aftermath of bottles and crumbs and empty glasses that clutter the table.’ When they entertain the Ratliffs invite not more than a dozen carefully chosen guests – a mix of artists, academics, editors and gallery owners, who eat their meal course by course, talking intelligently until the evening’s end. So different from his parents’ ‘cheerfully unruly’ parties, with no fewer than thirty people, mostly Bengali, along with their children, where there are so many courses that people have to eat in shifts, sitting wherever they can find place in the house, the table crowded with the pans the food was cooked in. ‘His parents behaved more like caterers in their own home, solicitous and watchful, waiting until most of their guests’ plates were stacked by the sink in order finally to help themselves.’

The biggest difference between Maxine and himself, according to Gogol, is her ‘gift of accepting her life … she has never wished she were anyone other than herself, raised in any other place in any other way … There is none of the exasperation he feels with his own parents. No sense of obligation. Unlike his parents they pressure her to do nothing, and yet she lives faithfully, happily, at their side.’

Gogol goes home more and more infrequently, phones less and less, making excuses, even telling outright lies. He goes instead with Maxine and her parents to their summer home by the lake in New Hampshire – a lotus eating paradise where her grandparents live. ‘The idea of returning year after year to a single place appeals to Gogol deeply. Yet he cannot picture his family occupying a house like this, playing board games on rainy afternoons, watching shooting stars at night … He feels no nostalgia for the vacations he’s spent with his family, and he realizes now that they were never really true vacations at all.’

Gogol’s mutation into Nikhil seems complete and wholly successful – till his father unexpectedly dies. At the time of his death his father has been living alone in Cleveland, having gone there for a short period on work, and it is Gogol’s job to sort out his meagre possessions in his flat. Caught up in the funeral rites with his mother and sister, when Maxine suggests that he get away with her ‘from all this’, he replies, ‘I don’t want to get away’, knowing that he cannot. For there is a story behind his name that prevents him from placing the hyphen neatly between Gogol and Nikhil. For Gogol was not just his father’s favourite writer nor ‘The Overcoat’ his favourite story – Gogol and The Overcoat have quite literally saved his life. As a young man, while traveling by train to see his grandfather, Ashoke’s train has an accident. He is almost overlooked in the dark by the search parties till someone sees a hand move and a sheet of white paper drop from it – Ashoke is rescued and the page that saved him is from ‘The Overcoat’ – he had been reading Gogol when the train derailed.

It is from the burden of stories like this that the immigrant cannot get away, Lahiri suggests, and which lay their claim on you in unexpected ways. Lahiri herself admits, ‘I never know how to answer the question, ‘Where are you from?’. His withdrawal from Maxine (who despite being overwhelming is right for him) leads Gogol into the arms of Moushumi, fellow-Bengali, fellow-sufferer of enforced Puja celebrations and parental expectations, and into a disastrous marriage.

Names feature in other significant ways in this book. Gogol finds himself discussing the origin of names at a gathering of Moushumi’s clever Western friends where a couple is searching for a name for their yet-to-be-born child, and he realizes that his and Moushumi’s will never appear in their books of names and despite the whimsy that they display in their talk, they would never name their children casually. Moushumi admits reluctantly that her name means ‘a damp southwesterly breeze’ almost acknowledging how ridiculous it sounds, and in the same breath she reveals to the assembled party that Nikhil is not his given name but his changed name. He has to own up to Gogol and they are mystified and bewildered that anyone would disown a name – the basic badge of identity. When Moushumi, expectedly, is unfaithful to Gogol, it is the name that seduces her equally – Dimitri Desjardins.

Other than playing with names to track the hide and seek of identity, Lahiri, less obviously, uses food. Ashima’s meals and the community meals during festivals and the thirty-strong parties – the luchis, the running aloo dum served on paper plates, the thick channa dal with ‘swollen brown raisins’ -- are the stuff of communal subsistence, a Bengali candle in the dark, an expression of conviviality and fellow feeling, innocent of all blandishments and refinements, and when one learns to know better, as Gogol does, cause for embarrassment. When Ashima puts together a meal for Maxine, Gogol thinks it ‘too rich for the weather’ and knowing that it has taken her over a day to prepare, he is embarrassed by the effort, the ‘for special occasions only’ dining room that the meal is served in, with its high-backed chairs upholstered in gold velvet. Lahiri admits, ‘Like most children of immigrants, I’m aware of how important food becomes for foreigners who are trying to deal with life in the new world. My parents have given up so many basic things coming here from the life they once knew – family, love, connections – and food is one thing that they’ve really held on to.’ (17)

Similarly, for Aslam too food is one of the ways of expressing ‘the glowing warmth that people who are born of each other give out, the heat and light of an extended family’. Kaukab cooks large, laden meals for her family get-togethers, meals that include the ingredients that they have been missing in England -- ‘bamboo tubes pickled to tartness in linseed oil, slimy edges that glued the fingers together as you ate them, naan bread shaped like ballet slippers, poppy seeds that were coarser than sand grains but still managed to stick like a dune when the jar was tilted, dry pomegranate seeds to be patted on to potato cakes like stones in a brooch, edible petals of courgette flowers packed inside the buds like amber scarves in green rucksacks, chilli seeds that were volts of electricity, the peppers whose stalks were hooked like umbrella handles, butter to be diced into cubes reluctant to separate, peas attached to the inside of an undone pod in a row like puppies drinking from their mother’s belly …’ As Kaukab breathes deep of the fragrance of bas (smell) – mati (earth), she inhales the scent of Pakistan’s earth deep into her lungs.

For both Lahiri and Aslam, the sign of Ashima and Kaukab ‘letting go’ is not their turning old or fat but when their housekeeping slips. Kaukab’s daughter is surprised by a crust of dal that adheres to a plate from a previous meal and Ashima is disgusted by the lingering taste of dishwashing soap on her own mug while she is sipping tea.

When Gogol sets off on his own to encounter America (which he does in large part through the Ratliffs) he discovers that food can be a visual and aural treat, a paen to relaxation and the good life, a culture in itself. ‘Maxine lights a pair of candles. Gerald tops off the wine. Lydia serves the food on broad white plates . . .’ Gogol is enthralled by the way the food looks – a piece of steak rolled into a bundle and tied with string, the meat baked in parchment paper, when he first meets Maxine’s mother her elegance and beauty are underscored by her standing in the kitchen, ‘snipping the ends of a pile of green beans with a pair of scissors’, by the appeal of ‘goat cheese coated with ash’; he is taken as much by the sound of the words that describe the food – polenta, risotto, bouillabaisse and osso buco, ‘Parmesan and Asiago cheese’; and above all, the quantities and varieties of wine. ‘My parents don’t own a corkscrew,’ he offers by way of apology to Maxine. All his mother can come up with is ‘glasses of frothy pink lassi, thick and sweet-tasting, flavoured with rose water’. And as with other things, with food too Lahiri contrasts the aspirational nature of immigrant experience with its contempt for its own.

With Maxine, if the food is romanced, with Moushumi it becomes the object of the romance itself, even a substitute for it. Gogol is watchful as Moushumi orders in the restaurant – their courtship is almost wholly played out in eating places – and Lahiri seems to suggest that the food and the wine they order and the way they order it are not just ready reckoners of assessment but the prism of their inner deeper selves, refracting the light and weight of their experience in tangents and colours meant subtly for the other. She also often switches to the present tense in the ‘food’ and ‘restaurant’ sequences. ‘She orders a salad and the bouillabaisse and a bottle of Sancerre. He orders the cassoulet. She doesn’t speak French to the waiter, who is French himself, but the way she pronounces the items on the menu makes it clear that she is fluent. It impresses him.’ At another meeting, in another restaurant, ‘Two glasses of merlot’, he says … ‘She orders what he does, porcini ravioli and a salad of arugula and pears. He’s nervous that she’ll be disappointed by the choice, but when the food arrives she eyes it approvingly …’ When he finally visits her house she is making Coq au vin out of a cookbook, which they proceed to cook and burn together. Moushumi and Dimitri’s meals together are as ‘ambitious’ as their romance – ‘ … golden puffed chickens roasted with whole lemons in their cavities … a salad topped with warm lamb’s tongue, a poached egg and pecorino cheese … There is always a bottle of wine.’

In grief and mourning too, it is ‘the enforced absence of certain foods on their plates’, the bland meat- and fish-less foods that mark the presence of those who are gone.

In On Beauty, Zadie Smith’s hommage to E M Forster’s Howard’s End, almost a hundred years later, with the feuding Belsey and Kipps families Smith replays the clash between Forster’s liberal-romantic Schlegels and Imperialist-practical Wilcoxes, plunging them into the heart of the multicultural debate (despite her protests that she is not ‘that’ multicultural) (18), reflecting its modernist and postmodern hues, and at the same time stands with her face turned away from it, indicating perhaps the way it is going to go. The Belseys mirror Smith’s own circumstances closely – a multicultural, multicoloured, multiracial, multicontinental family. Howard Belsey, a white British liberal arts academic, who has pulled himself up by his working class bootstraps – his father is a butcher, has moved from London with his African-American wife and their three children to teach at Wellington -- not quite Ivy League but an exclusive college in New England, USA. Here, Howard, the ‘radical art theorist’ clashes with the ‘cultural conservative’, ‘Sir’ Monty Kipps, a Trinidadian English immigrant, a formidable academic who has been invited to deliver a series of lectures at Wellington, and moves there with his wife and two children. Smith begins the novel with the Kipps and Belseys declaring, ‘We refuse to be each other’ (just as Kaukab and England and Ashima and America do) and it is this refusal that provides for much of the dynamics of On Beauty. For despite this refusal the families connect in several ways – in love, as Jerome Belsey and Victoria Kipps discover, or an aberration of it, as hit upon by Howard and the same Victoria, in friendship, that ties Kiki Belsey and Carlene Kipps, or plain hate-your-guts animosity as between Howard and Monty and between their daughters.

In On Beauty, Zadie Smith’s hommage to E M Forster’s Howard’s End, almost a hundred years later, with the feuding Belsey and Kipps families Smith replays the clash between Forster’s liberal-romantic Schlegels and Imperialist-practical Wilcoxes, plunging them into the heart of the multicultural debate (despite her protests that she is not ‘that’ multicultural) (18), reflecting its modernist and postmodern hues, and at the same time stands with her face turned away from it, indicating perhaps the way it is going to go. The Belseys mirror Smith’s own circumstances closely – a multicultural, multicoloured, multiracial, multicontinental family. Howard Belsey, a white British liberal arts academic, who has pulled himself up by his working class bootstraps – his father is a butcher, has moved from London with his African-American wife and their three children to teach at Wellington -- not quite Ivy League but an exclusive college in New England, USA. Here, Howard, the ‘radical art theorist’ clashes with the ‘cultural conservative’, ‘Sir’ Monty Kipps, a Trinidadian English immigrant, a formidable academic who has been invited to deliver a series of lectures at Wellington, and moves there with his wife and two children. Smith begins the novel with the Kipps and Belseys declaring, ‘We refuse to be each other’ (just as Kaukab and England and Ashima and America do) and it is this refusal that provides for much of the dynamics of On Beauty. For despite this refusal the families connect in several ways – in love, as Jerome Belsey and Victoria Kipps discover, or an aberration of it, as hit upon by Howard and the same Victoria, in friendship, that ties Kiki Belsey and Carlene Kipps, or plain hate-your-guts animosity as between Howard and Monty and between their daughters.Aslam’s world is marked by a Manichean struggle between two well-marked entities – the inside and the outside, ‘us’ and ‘them’ are clearly conceived and the characters too have clear conceptions of themselves as ‘for’ or ‘against’ something. With Lahiri the outlines are blurred, it is a quieter struggle with fewer obvious barriers to overcome, and though the differences may not mark/brand her characters so violently, there are two distinct worlds to be straddled all the same. In On Beauty, the boundaries are more tightly drawn (or more loosely depending on how you see it); the enemy, so to say, is within – in your own blood, in the colour of your skin, in the curl of your hair; the world (and your adversaries) is in the four walls of your house. All your battles have to be fought within/inside first. And it is in this, in redrawing the boundaries of the battle that Smith takes multicultural writing forward.

Howard Belsey is the quintessential modern Enlightenment liberal – while granting others their diversity, he believes in and embodies the triumph of reason over emotion, the rational over faith, is bookish and such a slave to his intellect that to him a rose is ‘an accumulation of cultural and biological constructions circulating around the mutually attracting binary poles of nature/artifice.’(19) A dyed-in-the-wood academic and theoretician, he strips things to their bare bones to ‘interrogate’ them and is uncomfortable with and even incapable of seeing them whole. For years he has been working on a book on Rembrandt – and his job tenure depends on its successful completion – his stance being to question ‘the culture myth of Rembrandt … his genius’. In Howard’s view, Rembrandt is not the ‘familiar rebel master of historical fame’ but merely a ‘competent artisan who painted whatever his wealthy patrons requested’; ‘neither a rule breaker nor an original but a conformist’. Only, his book never seems to get written, while Sir Monty Kipps who has taken the opposite position on Rembrandt – ‘retrogressive, perverse, infuriatingly essentialist’ – has not only finished his sizeable tome but it is doing very well. ‘Art is the Western myth with which we both console ourselves and make ourselves’, Howard intones year after year while his students dutifully take it down. Like a true intellectual he lives by what he believes and will not allow any representational paintings to hang on his walls; with his horror of superstition, tradition and ritual, he will not allow Christmas to be celebrated in his home and forever suspicious of the appeal to the emotions, even while listening to music he is on the lookout for ‘some metaphysical idea’ that may sneak in by the back door. Howard’s ‘academese’ more often than not confounds and intimidates his students, but his unintellectual, down-to-earth wife calls him to order with, ‘Howard, we’re not in your class now.’ In keeping with his liberal, politically correct self he is on the Affirmative Action Committee, is the Chair of the Equal Opportunities Commission and is all for gay and lesbian rights. And like all liberal multiculturalists he is perplexed when a conservative like Monty Kipps uses liberal arguments to buttress ‘retrogressive’ stands/politics/agendas.

Howard is up against the devoutly Christian, charismatic, natural leader of men, Sir Monty Kipps, who is also the more successful and self-possessed academic. The Kipps household believes that equality is a myth (one of the widely held beliefs of the opponents of multiculturalism is that the faith in diversity and equality cannot co-exist) multiculturalism a fatuous dream, that Art was a gift from god that he gave only to a chosen few, that literature was a veil for ‘poorly reasoned left-wing ideologies’, and that ‘being black was not an identity but an accidental matter of pigment’. Affirmative action, Monty Kipps argues, sends out the message to black children that they are not as good as their white counterparts, not as fit for the same meritocracy. Opportunity was a right that had to be earned and not a gift, and too often minority groups demanded rights they hadn’t earned. He abhors the fact that blacks are being used as political pawns, ‘encouraged to claim reparation from history itself’, and that such a culture of victimhood would continue to raise victims and perpetuate underachievement. ‘The coloured man’ he declares, ‘must take responsibility.’

At Wellington, Sir Monty wants to take the ‘liberal’ out of liberal arts. Using Howard’s own stick to beat him, he accuses the Howard caucus of privileging liberal perspectives over the conservative and suppressing right wing debate on campus. Everybody, he seems to be suggesting, according to Howard’s daughter Zora, gets special treatment – blacks, gays, liberals, women – everybody except poor white males. He tells liberals that they are ‘living in a fairytale’.

And true enough, the only thing Howard cannot countenance is an anti-liberal stance and opposition to his politically correct ideas. He cannot admit that Monty Kipps’ ‘reductive and offensive public statements about homosexuality, race and gender’ come from a deeply held Christian moral sense. In his own home, he cannot deal with his eldest son Jerome, a devout Christian, who runs away from his irreverent home into the right-wing arms of the Kipps family in London, proceeding to get engaged to their daughter, and thus setting off a chain of transcontinental interactions between the two families. In his email to his father, Jerome writes, ‘ … it’s very cool to be able to pray without someone in your family coming into the room and a) passing wind b) shouting c) analyzing the ‘phoney metaphysics’ of prayer d) singing loudly e) laughing.’ When it comes to the racial crunch at home the usually voluble Howard falls silent -- ‘he disliked and feared conversations with his children that concerned race’.

In deference to Howard’s full-whiteness perhaps, Smith gives him concerns that are intellectual, generic, absolute and objective. But he himself is a mess. While the other members of his family have more muddled concerns, they come off the more self-aware. Kiki, Howard’s African-American wife lives constantly with the realization of how much her ‘white’ connections have helped her rise in the world, alienating her from her own kind. Kiki’s great great grandmother was a house slave, her great grandmother a maid, her grandmother a nurse who inherited a house (that comes to Kiki eventually) from a benevolent white doctor and Kiki’s own marriage has elevated her, ‘a hospital administrator’ to the select academic community in Wellington. She is only too aware that she sails in a sea of white – ‘I don’t see any black folks unless they are cleaning under my feet’ and is guilty, and nervous, for instance, about what her Haitian immigrant maid ‘thought of another black woman paying her to clean’. And yet she is disappointed when a ‘disadvantaged’ black – this time a Haitian trinket seller – does not make contact with her, neither calling her ‘sister’, nor making any assumptions or taking any liberties with her. She is also aware of the attractions of her family – ‘Three brown children of a certain height will attract attention wherever they go. Kiki was used to the glory of it and also the necessity of humility.’ She imagines herself giving speeches to the guild of black American mothers on bringing up their children – ‘And there’s no big secret, not at all, you just need to have faith, I guess, and you need to counter the dismal self-image that black men receive as their birthright from America – that’s essential – and, I don’t know, get involved in after-school activities, have books around the house, and sure, have a little money, and a house with outdoor …’. At the same time, Kiki, who has grown fat over the years, also knows the tactical advantage of living up to clichés of black people and behaving in a way or affecting manners of speech that ‘she understood white people enjoyed’.

While Kiki’s ‘blackness’ is one of the ingredients of her being, her contribution to the movement of the novel come from her concerns as a wife – of having to live with her husband’s compulsive unfaithfulness and still not be done with loving him, and a mother – she is losing control over her children and coming to matter less and less to them. (Here she stands united with Kaukab and Ashima.) It is as a wife and mother that she reaches out to the sickly Carlene, wife of Monty Kipps, who she senses is similarly placed.

While Jerome, the eldest Belsey sibling finds that his family cannot take his ‘fellowship with Christ’ in their stride, the youngest, Levi, sixteen years old, is discovering the anomalies of being a privileged black with a white father. That white man your father? a friend asks doubtfully and Levi has to assure him that Howard is alright. Levi hangs around with Haitians, Cubans, Angolans and Dominicans, most of them illegal immigrants, and a set of Haitians selling CDs on the pavement become his friends and he gets involved in their cause. The compulsions of being ‘street’ and connecting with his ‘brothers’ make the sixteen-year old anxious; he is not above play-acting like his mother, often affecting a Brooklyn accent or others removed from his own – ‘’Preciate that, paw’ he riles his father with, imitating his mother’s southern roots. His sister Zora, in the relentlessly cruel manner of siblings, reminds him, when he is pretending to be from Bronx – ‘You live in Wellington. You go to Arundel. You’ve got your name ironed into your underwear.’ According to Zora, ‘in Levi’s sad little world if you’re a Negro you have some kind of mysterious holy communion with sidewalks and corners.’ She points out to her brother that it is ‘the worst kind of pretension … to fake the way you speak’ … to steal the grammar of the less fortunate. If a writer like Aslam can bring to bear the ways of seeing of subcontinental cultures or the sound of those voices, Smith subverts this position to show how they are devices of artifice, used to affirm stereotypes when it suits people, or that self-mockery too is a legitimate voice in the polyphony.

When Levi walks out on his part-time job in a global music store, in protest against the management’s making the staff work on Christmas day, he alone among all the employees – white and black – can afford to do so. But again it is Levi who is closest to the ground, cultivating a variety of black people, especially the ‘obstinately historical’ and so constantly reminded of how threateningly blacks are perceived. When he encounters certain old ladies on the street he wishes he had a T shirt that said, ‘I’M NOT GOING TO RAPE YOU’, and often when he enters his own home (and here, Smith belies her humour) he has to consciously counter the impression that he’s going to rob it.

However, when the family actually befriends a less privileged black boy, who does not have an education but a natural talent for poetry and a knowledge of music, once the initial attraction fades, they don’t quite know how to deal with him. Levi loses interest in Carl and moves on to the Haitian refugees (whose ‘cause’ is safer as it is a group cause), Howard inadvertently throws him out of a party in his house, and Zora, despite being a little in love with him is nervous about walking with him to college, afraid that his conversation was ‘a kind of verbal grooming that would later lead … to her family home and her mother’s jewellery and the safe in the basement.’ Levi’s way of dealing with the historical injustice of colour is to steal a priceless work of traditional Haitian art from the Kipps and return it to its ‘owners’ – the Haitian refugee group on the streets whom he has befriended. When the theft is discovered, suspicion first falls on Carl and only later does the truth come to light.

In On Beauty, food is not the great comforter. It is tempting (as well as logical) to attribute this to the fact that Smith herself is a second generation immigrant writer, writing of a more settled family. No longer a third world thing, food in the first world is the stuff of basic nutrition – we eat to live – or at best an offer of individual one-to-one solace. Kiki takes Carlene Kipps a pie as an offering of friendship, and later one to Monty Kipps to condole his wife’s death; if not, food is the stuff of gluttony, only the fat eat. It is the grossly overweight Kiki who is most associated with food, and Monty Kipps, tall and of imperious bearing (a euphemism for ‘fat’) who, whenever Kiki sees him, is almost always eating.

The family is no less central to On Beauty and to Smith (who admits to very strong family affections – ‘I'm extremely close to my younger brothers; family is everything’) (20) as it is to Maps and The Namesake and their writers. In Maps and The Namesake, we see subcontinental families – where family is all – roiling in their differences, unable to speak the same language and see the same world, while in On Beauty, all the sparring and the stridently different world views seem only to underscore the off hand but strong family bonds, which they do not owe in large measure to cultural ties. As with other things, the family is transformed here from a space of collective identity to one where individuals co-exist, where acrimony arises from a clash of individual dispositions rather than veering from a misinterpretation of cultural/religious norms or a miscarriage of family obligation.

IV

If the philosophy of multiculturalism is truly that of societies in flux, and has to reinvent itself for the twenty-first century to serve its world better, Smith with On Beauty is perhaps indicative of the direction it will take in literature. Multicultural writers and writing, Smith’s cues seem to suggest, must become more knowing, more adult, more responsible for their lives and destinies. In Aslam’s world the immigrant, newly off the boat, is wide-eyed and bewildered. His Kaukab’s children still hark back to an Edenic world of a naked Adam, his penis still uncircumcised, one with the birds and animals and plants that are a part of the primeval earth. With Lahiri, the child of the immigrant, her Gogol, has lost both the innocence and the certainty of his mother, but is still searching, a Jekyll and Hydean quest for identity, free from any nostalgia. With Smith, the comfort blanket of the past is gone. Her children are born whole, the consequence of their parents’ past, of circumstances similar to Aslam’s and Lahiri’s but without the luxury of being at a remove. Smith flings her characters into the deep end of the pool and bids them swim. Maps is, in many ways, a book about love. In the treatment of his characters, the delineation of their struggles and their foibles, what comes through with Aslam is his immense love for his world and its creatures – right down to his descriptions of nature and food. In fact, Aslam dedicates Maps to his father who advised him ‘to always write about love’. With Lahiri, the emotion is toned down to compassion. This has the curious effect of rendering their characters child-like in some ways, in making them appear if not helpless, at least less in control of their circumstances. Smith sees her characters, not less sympathetically, but with humour, and in that way of seeing seems to hand over to them the reins of their lives. Their colour and their culture mark them equally, but are not the mainsprings of their lives. Despite their vulnerability, they are characters who have truly come home, full citizens of a free world, though they may not be fully equipped to handle their freedom and we see them blundering and stumbling towards the light.

Successive generations of multicultural writers, as they find their feet in the new societies and their individual voices, might write too about the new world where all communities, if not equal may be equally commented upon and satirized, as a measure of comfort with each other. In On Beauty, if Smith has crossed the Forsterian world view with an Austenian comedy of manners, the next multicultural generation may find that wearing its identity lightly or seeing it become part of its skin, may give it a new voice and a new way of seeing the world..

Notes:

| 1 | ‘The Empire Writes Back’, Pico Iyer, Time, February 8, 1993. |

| 2 | This summary of the multicultural position has drawn from, among other readings, ‘What is Multiculturalism?’, Bhikhu Parekh, ‘Perspectives on Pluralism’, T N Madan, ‘Which Diversity?’, Kumkum Sangari, Seminar, # 484, December 1999, MULTICULTURALISM -- a symposium on democracy in culturally diverse societies, http://www.india-seminar.com/1999/484.htm; Kenan Malik, ‘Making a Difference: Culture, Race and Social Policy’, www.kenanmalik.com/papers/pop_multiculturalism.html. |

| 3 | Modern Europe, C J H Hayes, 1982, Concessional Edition, Surjeet publications. |

| 4 | ‘Which Diversity?’, Kumkum Sangari. |

| 5 | ‘Making a Difference: Culture, Race and Social Policy’, Kenan Malik, Which Diversity?’, Kumkum Sangari |

| 6 | ‘The Empire Writes Back’, Pico Iyer. |

| 7 | BookBrowse.com 2005 |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | ‘Ethnic or Postcolonial? Gender and Diaspora Politics’, Suchitra Mathur, social.chass.ncsu.edu/Jouvert/v4i3/smath.htm |

| 11 | From Introduction, ‘The Empire Writes Back: Theory and practice in posColonial Literatures’, Bill Ashcroft, Garreth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin, 1989, Routledge. |

| 12 | BookBrowse.com 2005 |

| 13 | ‘Maps for Lost Lovers’, Nadeem Aslam, Vintage Books, 2004. All quotations from the novel in this essay are from this edition. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | The Namesake, Jhumpa Lahiri, Harper Collins India, 2004. All quotations from the novel in this essay are from this edition. |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 | Zadie smith, On Beauty, Hamish Hamilton, 2005. All quotations from the novel in this essay are from this edition. |

| 20 |

The essay traces the ‘multicultural’ sensibility in contemporary Western fiction through works by three writers who have different relationships with their home countries. Nadeem Aslam migrated from Pakistan to Britain when he was fifteen; Jhumpa Lahiri, with strong Bengali cultural links was brought up in the US and Zadie Smith is part white English and part Jamaican. Since there is a discernible evolution in their positions as they move away from their home cultures, a question to be asked is whether a writer of a subsequent generation of today’s immigrant families will continue to remain a ‘multicultural’ voice or whether her/his voice could be eventually ‘assimilated’. In an earlier generation didn’t writers of the ‘mainstream’ enrich national literatures through their ethnic identities, be it Jewish (Malamud) or Armenian (Saroyan)?

Editor