|

|

Background This essay is intended as an appreciation of Aleksei German, a Russian filmmaker who is little known outside his home country and who passed away in February 2013 after having completed just four feature length films. His first attempt at directing, The Seventh Companion (1968), was co-directed with Grigori Aronov while his last effort – based on a science fiction novel by the Strugatsky brothers – Hard to be a God is apparently still in post-production.If endorsements are needed to justify German’s place in cinema, |

My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1984) was voted the greatest of Soviet/Russian films by critics in Russia and this is from a group of films which includes those by Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevelod Pudovkin, Alexander Dovzhenko, Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Paradjanov. Still, German has not been received well in the West and his last completed film Khrustalev, My Car! (1998) was met with a mass walk-out by critics at Cannes, where it was in competition because, to cite an obituary in The Guardian, it was ‘incomprehensible for long stretches and unforgivably unfunny in the endless scenes of manic visual satire’.

German is not an easy filmmaker to decipher because he appears to have reinvented filmic narration for himself in his later films and therefore demands attentive spectators capable of reflecting after they leave the hall. As attributes of his cinema, the depth of his images recalls Citizen Kane (1941) and his tracking camera is more fluid and mobile within constricted space than was even Max Ophüls’ (The Earrings of Madame de…, 1953). Ophüls has not been matched in the West for this ability, although Stanley Kubrick tried to emulate him. Group activity within each frame in the indoor scenes appears ‘casual’ but it is evidently the result of amazingly intricate choreography. Still, since one cannot locate much of the action in the logic of a coherent plot, the effect can be mistaken for cacophony. German deals mainly with the Stalin era but there is too much detail in his films for us to read a political meaning in them – at least the kind we are accustomed to. German is far too radical a filmmaker to remain unknown outside Russia and my purpose is partly to demonstrate that his methods even merit a reexamination of cinematic narration. The task of describing films which few people have seen, making the descriptions engaging and assessing the director’s fundamental achievements on the basis of the descriptions is not an easy one but I propose to undertake it. But before commencing a more thorough scrutiny I should perhaps begin by examining the thrust of German’s films individually and the sense made of them by critics –although it will be practical to restrict the local cultural references to which critics draw attention.

The effort in this essay will be to understand German’s methods as radical film practice the world over and not to account for them as the choices of a local artist. If David Lynch or Jean-Luc Godard will stand diminished if he is treated exclusively as an American or French artist, so too will Aleksei German if too much emphasis is placed on his Russian cultural antecedents. German responded to his own milieu but his explorations certainly have larger significance. If he was deeply influenced by Russian literature – especially poetry (1) – and makes repeated references to it, artistic creation and art appreciation do not always follow the same trajectory and the two processes may even be essentially independent.

The films

Aleksei German made his début at 29 beside the older and more experienced Grigori Aronov, then 44. The Seventh Companion is a film about an unusual hero (for a Soviet film): a Tsarist general who finds himself alternately in the camps of Reds and Whites, and who realizes that all the values he believed in have collapsed; a hero full of doubts and contradictions. German’s central approach is already found to be present here by critics: ‘the instability of historical roles, the overturning of ideological certainties and the elusiveness of the real’ (2).

|

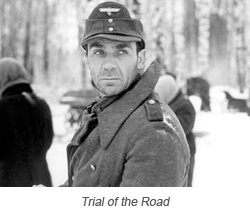

Trial of the Road (1971) is a war film which was banned for fifteen years and was released only in 1986. It tells the story of a Russian soldier, a POW who joins the Germans but defects once more to the Soviet side. Lazarev, a former sergeant in the Red Army who became a collaborator for the

Nazis in occupied territory, lets himself be arrested by the partisan

division because he wants to return to fighting the Germans. He is, however, willing to undergo every test of courage, submit to the inevitable humiliations and even let himself be shot as a traitor. The film has several other characters and Petushkin is a major who |

is ready to sacrifice a boat with hundreds of Russian prisoners aboard in order to carry out a sabotage mission against the Germans. He believes in military discipline without concession and takes comfort in the sacrifice of his son, who died hurling himself at a tank. Korotkov, the commander of the partisan division, is a simple man who trusts his own instinct and humanity more than the rules; he is adored by the men in his division. As may be anticipated, the film is about Lazarev proving himself in war but dying heroically. The film departs from Soviet orthodoxy in its depiction of the War – as perhaps exemplified by Yuri Ozorov’s 8-hour epic Liberation (1969) – by being ambivalent about many aspects on which Soviet films take sides. The factor which attracted the greatest official hostility was the film not overruling the possibility of Lazarev having taken Soviet lives in his dealings under the Germans. Still, while the film is a landmark achievement, it does not reveal the characteristics that mark out German’s later films. Its achievements can largely be subsumed under plot development, character study and resolution and do not prefigure the formal innovations of his remaining three films.

|

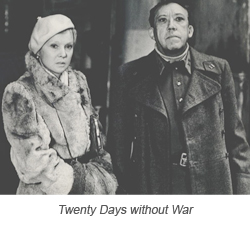

Aleksei German’s next work Twenty Days without War (1976) (based on a novel by military journalist Konstantin Simonov) was for a while the only one of his films seen outside the Soviet Union. The film describes the adventures of Major Lopatin a military journalist during World War II, who goes to Tashkent (Uzbekistan) at the end of 1942 to spend a 20-day vacation following the Battle of Stalingrad and to witness the shooting of a film based on his wartime articles and where he is romantically involved with a local woman. The title ‘twenty days without war’pertains to this period when he learns how the romantic views of combat held in far flung places like |

Tashkent bear no relation to the harsh realities of front line warfare. The film was banned presumably because of its antiwar theme, but was released in 1981 after interference from the film’s screenwriter, the novelist Simonov, a close friend of German’s father, Yuri German, and highly regarded by the Soviet establishment.

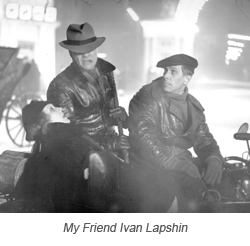

Both of German’s war films are relatively conventional in their narrative methods and do not present the difficulties for international audiences that My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1984) is almost certain to. This film is set in 1935, an important year for the Soviet Union because it was the year following the assassination of Sergei Kirov, who headed the Party in the Leningrad region. Kirov’s murder was apparently the handiwork of Stalin himself but it later became a pretext for him to

|

initiate the purges in which a large number Bolsheviks were liquidated. German’s film makes no mention of either the purges of 1936 or Kirov and the only fact about the film to give it this political significance is the year in which the story is set – in a provincial town in the Russian north with the narrator being a boy now reminiscing as a elderly person. The locations are the offices and habitation of the town’s police force, under the direction of Ivan Lapshin. Lapshin lives in an apartment in which an indefinite number of people are living together. Signs of the time are all too evident but there is no emphasis to drive the story in any discernible political direction. The plot ostensibly revolves around Lapshin’s pursuit of a dangerous |

criminal and gang leader named Soloviev, whose actual crimes remain unspecified. The only evidence we see of his handiwork are some frozen corpses being carted out of an underground shelter a third of the way into the film. Somewhere closer to the end Lapshin’s men surround a miserable farmhouse in which Solovev is apparently quartered and casually guns the criminal down when he surrenders to him in the snow outside. Equally central to the film is Lapshin’s relationship with an actress. A troupe has arrived to perform an agitprop play and the actress is playing a reformed prostitute who chooses to work on a canal. In order to make her performance more convincing, Lapshin introduces her to an actual prostitute who, he tells the actress at the end of the film, is on her way to a labor camp. Another important character in the film is a writer and intellectual named Khanin, with whom the actress – Lapshin attempts to court her – is in love.

|

Aleksei German’s last completed film Khrustalev, My Car! is also set in a key year for the Soviet Union – 1953, the year of Stalin’s death. In the film Major General Klenski is a Jewish neurosurgeon arrested for his complicity in the ‘doctor’s plot’. Shortly before he died on March 5, 1953, Stalin accused nine doctors, six of them Jews, of plotting to poison and kill the Soviet leadership. The innocent men were arrested and, at Stalin's personal instruction, tortured in order to obtain confessions. The unfortunate physicians were lucky in comparison with Stalin’s other victims. The dictator died days before their trial was to begin. |

A month later, Pravda announced that the doctors were innocent and had (except the two who died) been released from prison.

In German’s film Klenski lives a privileged life with material comforts, family and mistress until he is arrested and taken away. Confined in a narrow space – the back of a van – in wintry conditions, Klenski finds himself assaulted sexually until, strangely enough, the vehicle in which they are traveling is stopped; he is given back a car and chauffeur and apparently his rank. He is driven to a forested area where he is escorted to a dacha in which an old man is dying. Several people are attending to him – servants, several nurses and a fat, slovenly man who appears to be in charge. The dying man who has soiled his sheets has apparently had a cerebral hemorrhage and Klenski is now required to save him. Klenski stammers that that this would be impossible and is immediately threatened with execution. Eventually he asks the fat man if the dying person is his father. “Well said,” the fat man replies, “He is, in a way, father.” At that moment a breeze blows through the room, a wardrobe creaks open and Klenski sees the famous white uniform hanging there. The dying person is Josef Stalin and the fat man, Lavrenti Beria, chief of the NKVD, the Soviet secret police. It is too late for Klenski to perform any service except to make Stalin ‘fart’ and he does this by pressing the dictator’s hairy belly, which is smeared with excrement. A while later – and after the corpse has been duly removed – Beria is neatly shaved and ready to leave. He shouts to his man Khrustalev to fetch his car and that is the significance of the film’s title (3). Klenski is also allowed to return home although this is not the note on which the film concludes.

Interpreting Aleksei German

German’s films are not difficult to interpret in the normal sense in that they are not ambiguous but tend to incorporate so much detail that we cannot be certain of what detail is significant. They are markedly ‘polyphonic’ – which a term introduced in the essay The Development of Form in Soviet/ Russian Cinema which is also in this issue of Phalanx. The characteristic which makes them difficult to interpret even as the story they tell is broadly understandable is that they do not follow classical causality, which even European art cinema depends upon.

The classical Hollywood film presents psychologically defined individuals who struggle to solve a clear-cut problem or attain specific goals. In the course of this struggle, the characters enter into conflict with others or with external circumstances. The story ends with a decisive victory or a defeat, a resolution of the problem and clear achievement or non-achievement of the goals. The principal causal agency is thus the character, a discriminated individual endowed with a consistent batch of evident traits, qualities and behaviors (4). Post-war European art cinema loosens the causal linking by deliberately admitting accidents into the narrative and presents characters without clear-cut goals, but it still defines itself in relation to classical cinema (5). Both classical Hollywood cinema and European art cinema employ linear narrative based on causal linking – the latter attempting not to fulfill the expectations it sets up as the former does. Interpretation of the ‘ambiguities’ of art cinema therefore revolve around recognition of the deliberate violations of classical storytelling. In a film like Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960), for instance, it depends on our interpretation of motifs like the unexplained disappearance, the aimless search, the unexplained crowd behavior in the sequence involving the woman celebrity and the ‘prohibited’ camera angles – like the one in the ghost town when the protagonists are viewed as if by an intelligent but indifferent presence.

In neither classical cinema nor the art film are we ever in doubt as to what events are crucial to the plot but this is not the case with German’s films which are virtually plotless. His films are never without an intelligible story but the elements of the story are so submerged in incidental visual and aural detail that we are unable to identify the events which will move the narrative – for which we need to reflect on the film after it is over. Each of the three films by German being examined here has a protagonist but rather than the story following him closely, the camera often follows other stories in the milieu without trying to exhaust any one through explanations. It is the perhaps the digressions in the film not supported by explanations which make German’s films unintelligible over large sections but everything still comes together on reflection although one is not certain how this happens – at least after a single viewing. The following examination of his films which add up, hopefully, to an interpretation of his work was possible only after repeated viewings and some reflection. In the other essay The Development of Form in Soviet/Russian cinema, I try to show how post-Soviet cinema displays ‘polyphonicity’ because of the conclusion of the grand narratives connected with the USSR – and the consequent liberation of the multiple voices which had once been subordinated to them – and this notion is crucial German’s films.

Twenty Days without War (1977): National history and private memory

The film begins just after the Battle of Stalingrad but with Leningrad still under siege. A group of soldiers on a beach are bombarded and shot at by some German planes and they take cover but one of the men does not survive. Major Lopatin (Yuri Nikulin) is entrusted with the task of carrying news of his death to Tashkent which is far away and untouched by war. Lopatin is a war correspondent and is also going to assist in the making of the film at Tashkent. Almost immediately after this, Lopatin is seen on a train to Tashkent in Central Asia.

On the train Lopatin meets a soldier whose name is not revealed to us but who tells Lopatin his own story. The story involves his wife’s unfaithfulness when he was at the front. The soldier’s monologue is an intense one and could well be out of Dostoyevsky’s House of the Dead – so much is the man on the edge and trying to restrain himself from some dreadful act. But Lopatin neither consoles him not gives him counsel; he only agrees to write a letter for the soldier. Later, in Tashkent, Lopatin sees the soldier again but the two do not acknowledge each other. This can be contrasted with a comparable sequence in Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Cranes are Flying (1958) in which the doctor attends to a wounded man in a similar position and comforts him. In Twenty Days without War, there is no sense that Lopatin and the soldier’s respective existences can be brought together while in Kalatozov’s film there is ‘human concern’ attempting a coalescing of different lives subordinated to a common destiny.

There are other sequences in Twenty Days without War which reinforce the same sense of lives not coalescing. Lopatin is required to extend solace although the woman to whom he carries news of her dead husband breaks own and simply asks him to leave. Lopatin’s own former wife is in Tashkent and living with another man. He visits her and signs some documents annulling their marriage. His ex-wife asserts that she is happy with the new man in her life but breaks into tears when Lopatin affixes his signature, blaming him for the break-up because his work was so important to him. Lopatin cannot listen and hurries out of the house, but runs into a woman named Lina with who he had exchanged glances on the train. She is known to his former wife and is a seamstress. The two leave together and encounter other people on their walk. Lina’s husband ‘ran off’ before the war and she lives with her daughter. Lopatin is now known in Tashkent and a woman and her son approach him hesitantly. Her husband was last heard from before he went behind enemy lines but his friend turned up recently to hand over his watch, which the husband wanted given to her. Her husband has not been heard from for four months but her son says this is natural. Is that true and is it natural for a man to send his watch to his wife when he is not in danger?

When Lopatin proceeds to the location where the film based on his writing is being shot, he discovers that not many people know what war is like. The self-important party ‘consultant’ (who saw action in the Civil War) has read some regulations and believes that soldiers should wear gas masks and helmets at all times – to be in readiness for battle. Some actors also wear medals, believing it to be the dress code for a soldier on the battlefield. Lopatin disabuses the actors of some of these notions and answers questions about the experience of war. He concludes by making a patriotic speech extolling the people of Tashkent from assisting the nation at war.

Having to leave the next day Lopatin visits Lina for the last time and the two spend an intimate hour together, even as Lina’s daughter keeps calling out to her from somewhere outside. Lina cannot see him off at the railway station and the two will probably not meet again. The film ends with Lopatin back on the battlefield amidst shelling. A newly arrived lieutenant – who has just chided a sergeant for not addressing him correctly – is expressing happiness after a severe bombardment that he is still alive because he thought it was all over. “It is only beginning, Lieutenant,” a soldier assures him, “Berlin is still a long way off.”

Twenty Days without War is the most linear of the three films by German being examined but one still gets a sense of its ‘plotlessness’ from the description provided. The narration begins as a voiceover, implying that the film represents Lopatin’s memory of his visit to Tashkent and that justifies its episodic character. The recounting in German’s film is not subjective and from Lopatin’s viewpoint and we witness things that Lopatin could not have seen (6) but he is still at its centre. The film captures a view of the periphery of the action and unlike the centre of the action in which there is forced consonance in the presence of a common danger, the periphery allows the narrative to accommodate some polyphony.

Critics writing on Soviet cinema tend to place their evaluative emphasis on each filmmaker’s courage to ‘reveal the truth’. This suggests that the most important aspect of Twenty Days without War to strike the critic will be Lopatin’s trying to correct the heroic view of the War being propagated in Tashkent (7) – since most other Soviet war films of the period were still being made in the patriotic mold (8). But German’s achievement is more radical than this ‘courageous’ aspect of the film, his trying to get at a more ‘truthful’ picture, as it were. This lies in the ‘polyphonicity’ accommodated by the film’s narrative, the sense of individual trajectories not subordinated to a common national history.

Accounts of German’s filmmaking methods bring out a curious contradiction. While he is extremely attentive to physical detail pertaining to the periods he deals with, for which purpose he relies on personal memories, he also exhibits a general indifference to historical accuracy (9). A hypothesis explaining this is that personal memories are more reliable than historical memory, especially when the latter has been so ruthlessly placed at the service of the state. It should be noted, however, that this is not specific to the Soviet state because all nation states tend to act thus, i.e. give the chronology of events a teleology leading up to a development like independence or a politically defining happening like a revolution. Every major event for over a hundred years before Indian independence, for instance, is interpreted as a step towards the independent nation (10). The Soviet Union was different only in its conviction that doctored history was ‘theoretically correct’ since history had a discernible direction which neutralized the effects of accidents and random occurrences (11). Twenty Days without War granting equal legitimacy to multiple trajectories and accommodating their polyphony is perhaps a way of subverting the subsumptive characteristics of historical memory which has the characteristics of authorial narration in the Bakhtinian sense. Bakhtin, while discussing Leo Tolstoy, notes how the propagandizing impulse in the novelist leads to a narrowing-down of ‘heteroglot social consciousness’ (12).

In Twenty Days without War, Lina’s story has a trajectory which hints at less than happy times before the War. Her husband ‘running away’ is even reminiscent of the father ‘leaving’ in Mirror. As opposed to the emotions in Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Cranes are Flying which dwell on national catastrophe in which personal loss is only a constituent element, personal loss is primary in the various trajectories charted in Twenty Days without War. The film is radical in its approach but it can hardly be asserted that it has an explicit political purpose directed against the Soviet state or that it debunks the ‘Great Patriotic War’. Its radicalism, instead, consists in its finding a formal way to deal with events of the past – which are still personally recollected – without subordinating them to the dominant discourse of Soviet national history. If the film’s narrative – which is perhaps less than a ‘story’ – is resolved through the relationship between Lopatin and Lina, the resolution is not mediated by history as is usual in war films everywhere. Even in Terrence Mallick’s The Thin Red Line (1998), for instance, the narrative is resolved when Pvt.Witt (who was a deserter) acknowledges the larger cause by giving his own life to it.

|

A last aspect of German’s film which makes it a significant formal achievement is his use of ‘choreography’. The frames of the film are perpetually crowded with activity of various sorts, people move in and out of them usually without their being implicated in the action. The sense to be got is of the numerous personal trajectories disturbed by and not in consonance with the war effort. There is also a sense of the milieu being unstable – and Tashkent itself appears to be a temporary camp of sorts. In The Cranes are Flying and most other war films even from Hollywood, the domesticenclosure is a stable one with the promise of domesticity resuming. In German’s film, the ‘choreography’ adds to the sense of domestic instability. |

The film concludes with Lopatin carrying on with his part in the war, with no stability to anticipate when it is over; the disturbances will continue as before the war.

My Friend Ivan Lapshin (1984): The periphery of the cataclysm

If the action in Twenty Days without War takes place in the periphery of a cataclysm, so does that in My Friend Ivan Lapshin although the ‘periphery’ now is in time rather than space. The film begins with an unnamed narrator describing the happenings in a small town nearly fifty years back, in 1935, perhaps when the arrests of the Great Terror were beginning. As a boy he lived with his father in a boarding house managed by the stern Patrikeyevna and among those living there was Chief Inspector Ivan Lapshin (Andrei Boltnev), who was his hero.

The film is episodic and shifts from story to story with many of the contextual references not being provided. Okoshkin who lives at the boarding house is also a policeman although we discover this only later. The camera (cinematographer Valeri Fedosov, who also shot Twenty Days without War) does not always follow Lapshin – who is nominally the protagonist – but also tracks various other people and movement, without explanations being provided. In the first sequence, for instance, there is the mimicry of an Italian airplane dropping bombs over Abyssinia and a chess game between two people in which José Raúl Capablanca the Cuban Grandmaster is mentioned. This same kind of ‘noise’ – random events not tied to an obvious plot but taking up screen time – is also in evidence in Twenty Days without War although the camera nonetheless follows Lopatin much of the time.

The fact that Ivan Lapshin focuses on neither the narrator nor the eponymous hero is also central because the film is perhaps not so much about Ivan Lapshin as about people ‘befriending’ a policeman in an authoritarian regime. Significantly, while the camera follows so many people and their activities without providing a logical basis for why it is doing so, its apparent interest in them is belied when we never learn what happened to any of them in the fifty years after 1935, not even to Lapshin. The narrative is deliberately left without focus as though to assert that all people would be of equal interest if they all met roughly the same fate.

To give the reader a deeper sense of the film’s unfocused narrative, we see Lapshin waking up with tears in his eyes but not giving reasons except, a little later, that he ‘dreamt of an airplane’. At another moment he awakens sweating and mentions the Civil War in which he sustained an injury but, “We were still happier then,” he asserts ruefully. Lapshin is engaged in pursuing the Soloviev gang which is a ‘gang of ruthless criminals’ but we are not told much about Soloviev although we see frozen corpses being loaded on to a truck in winter. “We’ll clear the land of scum and plant orchards and still be around to enjoy them!” declares Lapshin optimistically as he rides his motorcycle across an arid stretch of land.

The key relationship in the film is the one between Lapshin and Natasha, actress in a drama troupe preparing to put up an agitprop play apparently about criminals being reformed through labor. Natasha uses all her charm on Lapshin and he arranges for her to meet a real prostitute so she can lend her role some authenticity. Lapshin is courted by the troupe because he is important in the town and he arranges for them to get some firewood. Another character making his appearance now is Khanin, Lapshin’s friend. Khanin is a writer, journalist and intellectual although all we are told about him is that his wife died from diphtheria six days ago, about which he appears quite cheerful. Khanin is mischievous and gets Natasha to impersonate Okoshkin’s ‘abandoned wife’ in public as a prank.

Khanin has no place to stay and we are not told much about him. All that we know is that he moves into Lapshin’s boarding house and tries to shoot himself in the bathroom. But the cold metallic taste of the barrel makes him gag and he tries putting the revolver to his temple and then his forehead until he fires it accidentally into the bathtub, when Lapshin comes in, wraps it up and hides it away. Khanin’s dead wife cannot be the reason and the poet Mayakovsky’s suicide is later casually invoked by him, suggesting a political cause. By this time, his relationship with Lapshin having deteriorated after Natasha’s prank, Okoshkin moves out of the boarding house to live with another actress from the same drama troupe, a woman senior to Natasha. Later on, Okoshkin moves back into it, having apparently had enough of the woman.

The climactic action in the film happens when Lapshin and his men surround a two-storied farmhouse in which Soloviev has holed out. It is foggy and miserable people sit around in the passageways while Lapshin searches in the rooms until he finds the man he is looking for. But Soloviev escapes, assaults Khanin outside and takes shelter some distance away. Lapshin has his men counsel the criminal to surrender but, when Soloviev throws his gun down and surrenders, Lapshin shoots him dead in cold blood and walks away from the scene.

Lapshin has been harboring feelings for Natasha and goes to her apartment, climbs up to it using a ladder provided by an assistant – much against her entreaties. In the apartment even as Lapshin prepares for some intimacy, Natasha reveals to him hastily that it is Khanin that she loves. Like many of the other segments in the film this sequence too loses much in the telling. It is evident that Natasha knows that Lapshin would make a much better ‘relationship’ for her than Khanin, who is a maverick and given to avoidable sarcasm. The writer, for instance, finds a tiny scrap of newspaper in his soup and tries to read its political message. At the same time, Natasha loves Khanin rather than the unsophisticated policeman but realizes that she has hurt Lapshin although the policeman attempts to look unconcerned. Natasha tries, therefore, to comfort him through kisses even as she is rejecting him – wishing aloud ‘how nice things might have been with him’ since there is really no man in her life.

In the last segment Khanin is preparing to depart on a river boat and Natasha, without too much hope, entreats him to take her along while Lapshin is standing by impassively, smoking a cigarette and gazing into the distance. A band is playing military music and the air is faintly festive. Khanin gets on to the boat and Natasha goes off in another direction after bidding a dutiful goodbye to Lapshin. The policeman now joins his men and climbs on to a truck carrying them. The film concludes with the narrator telling us how much the town has changed since then and we see the town as it is now, stretched further on the other side of the river and with more than two tram lines, which is all there were in 1935.

|

It is difficult to imagine a non-Russian audience responding enthusiastically to My Friend Ivan Lapshin because it is so dependent on the evocation of a year that only means something in the former USSR. If the film is reminiscent of Federico Fellini’s Amarcord (1973) (13), which also deals with a year in the narrator’s life, German’s film hardly charms us in the same way. There are local allusions not explained like the fox and rooster shut into the same enclosure – a social experiment of sorts – until the fox eats the rooster. There is so much detail – accentuated by the depth of the images – that one is unsure where its focus lies. The use of deep focus by German is markedly quite different from its use in Citizen Kane in that it complicates the narrative rather than disentangles it. |

Phrased differently, the surplus of detail prevents us from reading the film in terms of plot, and the causal connections are left uncertain and this is confused further by bits of overlapping speech which do not reinforce a single whole – unlike that in a Robert Altman film in which dialogue which is of no great consequence can be identified and given less attention. My Friend Ivan Lapshin is based on stories by Aleksei German’s father Yuri German and most of the real people upon whom the characters – including the policemen – are based were executed in 1937-8 (14). The film may be poised at an instant of ‘quiet’ or a moment when history was steadying itself before an assault and German may be trying to capture a moment akin to that before a tsunami. The moment before a cataclysmic event is not ‘still’ in itself and the tranquility is in retrospect when the elements of daily life, because they are due to be rendered insignificant, are paradoxically made memorable. To further the parallel with Amarcord, the year in Amarcord is memorable because it is the year of Titta’s mother’s death while 1935 in Ivan Lapshin is made memorable by what commenced in 1936.

This last observation furnishes us with another clue pertaining to the ‘plotlessness’ of German’s two films. As already argued, plot and causality find correspondence in teleology but the political cataclysm just beyond the action in Ivan Lapshin is so horrific that the causal elements implicated in the film’s action lose significance. But since each event from 1935 is itself strongly recalled, the period will perhaps be remembered as a series of luminous but discrete moments not bound together as effect to cause. This may be comparable to how the effect of a municipal scandal in 1945 on local lives in Hiroshima will be remembered.

As a last observation about the two films dealt with, a question of importance may be why there is no evidence of domesticity in them. This aspect of Twenty Days without War has been already explored but, in Ivan Lapshin, the narrator and his father live without their mother in a boarding house and she is not mentioned. Although there is a hint of romance, heterosexual attachments do not prove stable; Natasha is left with neither Lapshin nor Khanin. Okoshkin resumes his life in the boarding house after leaving the actress. There is no evidence that a political message is concealed here about Stalin’s USSR and family life. Still, in films set in cataclysms like war there is a promise of domesticity resuming afterwards because of a happy conclusion to the disturbance (15). The time in which they are set is politically unstable but only temporarily, which is not the sense in German’s two films. To use an analogy, the breakdown of domesticity in them (and also The Mirror) may be like the ionization of the atmosphere prior to a storm, which had not fully passed even in 1984.

Khrustalev, My Car! (1997): nation and structure

Any account of Khrustalev, My Car! will tend to relate its plot – as I did earlier – but the primary value of the film lies in its conclusive defeat of the plot, if that is actually possible. The film, in black and white, deals with the travails of Major General Klenski, a surgeon and the head of a psychiatric hospital in Moscow in February-March 1953 and is nominally as recollected by his son, then around ten, and related in a voiceover. The film begins in a dark Moscow with a stoker trying to warm himself on the hood of a parked car – which unfortunately belongs to the NKVD. German is extremely attentive to the milieu he is depicting in its physical detail but without resorting to explanations. Klenski lives in a former aristocratic mansion of some sort which has now been split up into several small dwellings apparently occupied by families of some influence. The crowded section he lives in – well appointed with furniture and with ancient bric-a-brac perhaps from the Tsarist era – houses, apart from the members of his family including his mother, sister, two children (Jewish cousins) from Lithuania whom they are sheltering. Klenski is shown to be an ebullient sort given to pranks, and his household is not an aristocrat one. Children spit at mirrors; Klenski dips his fingers into his teacup; gymnastic rings are installed in the living room on which he works out; people eat whenever they please at a handsome dining table, which is never completely cleared of the dishes. The household is chaotic and German uses deep focus and a fluid camera to show people clashing in the course of their chores and the children being uncontrollable. Klenski’s boy, for instance, has a wolf’s snarling head that he keeps thrusting into people’s faces. To make it more frantic, the different households are situated so close to each other that one is never sure which people belong to Klenski’s household and which are the neighbors. There is also such a large amount of talk – curses from the adults and rhymes from the children – that the film cannot be subtitled fruitfully in the service of a linear narrative. This is the milieu as portrayed – in which Klenski gradually understands that he is in danger. The stoker arrested in the first scene was arrested outside Klenski’s residence and the NKVD may have been watching Klenski, although that is not specified.

Since much of the action is in the street and there is quite a bit of unexplained action it would require several viewings of the film to connect up – if they can be connected up at all. One man seen walking with an umbrella in an early segment whistles harshly and this is a sound repeatedly associated with the secret police – beginning with the opening scene. The man with the umbrella may be an agent provocateur because he later arrives at the Klenski residence and insinuates that he is bringing a message from the General’s ‘sister in Stockholm’. Klenski assaults him later when he reappears after being pushed roughly out, again making enquiries. The street scenes are not orderly and there is the familiar sense of discord – emphasized by minor traffic accidents in the icy streets. Another strategy seemingly employed by German to underscore the randomness is to have people breaking their actions as if to attend to other business – giving us the sense that their actions have not been completely thought out. The NKVD ‘provocateur’, for instance, who is walking carelessly along a pavement, turns abruptly towards the opposite side – because of a hand stretching out of a basement window to reach for a discarded cigarette butt. The ‘provocateur’ uses his umbrella to push the cigarette to within its reach and then resumes his journey. A motif which is repeated is that of the convoys of black limousines rushing around Moscow in the snow at dead of night, carrying deep portents of a political crisis.

|

That he is under suspicion gradually comes upon Klenski. There is some talk of the ‘Doctor’s Plot’ and the arrest of Jewish doctors on charges of attempting to poison top leaders and Klenski is Jewish. He runs his hospital like a personal fiefdom and the sequence set in the hospital is constructed like a weird musical, but without the music. We are familiar with the workplace musical – drawn upon by Lars von Trier in Dancer in the Dark (2000) – and this kind of film had its counterpart in the USSR – showing people at work as in Grigori Alexandrov’s The Shining Path (1940), which is set in the textile industry. German is apparently |

parodying the workplace musical in the segment in which Klenski arrives at work to be met by his anxious assistants, eager to wipe his face, which has become sweaty indoors and his woman assistant anxious to minister to him sexually. Particularly bizarre are the patients – their heads shaved and the sutures on the craniums not removed yet – participating in the energetic goings on. The psychiatric institution was later used routinely in the USSR as a means of dealing with dissenters and experiments had apparently begun even in the Stalin era. The segment in the psychiatric institution is closer to parody than pastiche and concludes with Klenski meeting his double, who seems to enjoy all his own privileges. What a ‘double’ is doing here is difficult to say but we are aware that the double always has a role in a totalitarian set-up. Doubles, for instance, were often used when ‘confessions’ had to be recorded during show trials. Since German never explains himself – and there is so much peripheral action to defeat every possibility of a plot – it is difficult to say when Klenski becomes aware that he is in danger. But at some point he decides not to get back home but watch it from a distance. Here again, we do not know what he sees but he attends a party after that, one also attended by other uniformed state functionaries. Klenski makes one or two unguarded statements (‘When Nero dies, there will be some lovely executions.’) and is admonished by his hostess (‘I will not allow you to speak of Him like that.”) There is also some casual talk about the success of longevity research being doubtful – since the researcher died at 51. The highpoint of the evening is Klenski trying to get a large dog drunk. After this he returns to his office, exits by a back entrance, jumps over a wall and makes for his mistress Varvara’s apartment. She is a teacher of Russian literature and he requests to stay the night. This scene is wonderfully poetic – there is snow outside and Varvara’s mother in the next room is anxious about who is visiting her daughter at this late hour. The cat, which is trying to get at the carp just brought in by Klenski, is punished by being dunked in the bathtub. A little while later, it is arching its delicate way past the sleeping couple. As with My Friend Ivan Lapshin, the film is also reminiscent of Fellini’s work in the wonderfully poetic moments that abound, but Fellini pushes politics out of the picture (as in Amarcord when he deals with Fascism farcically). Fellini’s approach is primarily nostalgic and the subordination of the other elements to authorial narration is complete. But German is dealing primarily with the memory of a political world with too much independent significance. The implication is that political repression cannot subdue the richness of the world and the film is essentially a paean to this notion. The parody, the satire, the brutality and the lyricism in the film therefore represent the polyphonic elements resisting subordination to both the discourse against repression and memories of the period to the authorial voice.

The second part of Khrustalev begins with Klenski submitting to arrest and this is made to seem inevitable because he is shown to wait at a prearranged point to be picked up when he is assaulted by a gang of boys – apparently habituated to such indulgences. One imagines that the capricious brutality of the state will create similar propensities among the citizenry. The ‘pick up’ of the accused itself is a ceremonial affair with a photographer also present but the truck conveying him and some others is makeshift and the group is quickly transferred to a vehicle which doubles as a transporter of wine. After a ride on which Klenski is sodomized by his companions – who later demonstrate that they bear him no ill-will – the vehicle stops in the fog and the prisoners relieve themselves. “Can you let me go?” Klenski requests the guard. “Go where?” asks the guard in reply.

After Klenski’s car, driver and rank are restored to him, he is taken to a spot where he needs to freshen up and he meets his double – who takes a cigarette from him ‘for old times sake’ – once again. Here again there are no explanations but a double has many uses. Perhaps, if Klenski had been dead, the double would have taken his place at the dying Stalin’s bedside.

There are conflicting reports of the filming of the climax in Stalin’s dacha and while one view is that German filmed it in the actual dacha, another is that he painstakingly recreated it. But there are apparently factual inaccuracies regarding who was present at Stalin’s death and the actor who plays Lavrenti Beria also does not resemble the actual chief of the NKVD. Still, as already argued, the history of the USSR has not been reliable and German’s creation of ‘artistic truth’ depends, essentially, on his questioning of ‘historical truth’.

Film-makers have portrayed decisive historical moments through fiction in several ways and the most popular one has perhaps been for the narrator’s eye to be in proximity to the leading historical players – as in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982) or Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012). An equally common one has been for the viewpoint to be that of the small man – the Nazi destruction of Warsaw from the viewpoint of a Jewish victim as in Roman Polanski’s The Pianist (2002). Scrutinizing the two possible approaches (16), it would appear in both of them that ‘national history’ is privileged – with the filmmaker having discernible links with the nation. Even Schindler’s List (1993) can be categorized thus because the film deals with the prehistory of the Jewish ‘nation-to-be’ (17) and is by a Jewish film-maker. Oliver Hirschbiegel's Downfall (2004) also deals with ‘national history’ even if the emotions associated with the nation are different. Rather than being political, ‘national history’ is a metaphysical influence because it implies a common destiny binding people (who are not social equals) together. Everyone partakes equally in the destiny of the nation, is the sense, whether Hitler or the unknown women attendants who share the Führerbunker with him.

|

A factor linking the various films dealing with national history is that they are ‘monophonic’ and it may be the ‘metaphysics of nationhood’ which is responsible. Khrustalev, although it deals with a turning point in national history, is polyphonic and Klenski, Beria and Stalin, emphatically, do not share the same destiny. This is not only because Stalin, unlike Lincoln, Gandhi or Hitler (as portrayed in Downfall), is a villain whose death simply means deliverance to the people. Many of these films about political villains still imagine a nation with the villain or tyrant excluded. As |

instances,one recalls American films from the counterculture period in which functionaries of the state and/or military leaders are designated villains (as in Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man, 1970) but, rather than deny the nation, the films reconfigure the nation as a community from which the state is kept out, and one can conceive of Khrustalev on the same lines. But German’s film, instead, makes an effort not to configure a ‘nation’ by organizing a cohesive community around its protagonist - as happens, despite its polyphony, in My Friend Ivan Lapshin. But if the nation is not inscribed in Khrustalev, there is still ample indication of a political structure in which everyone is implicated. Rather than being a metaphysical binding force, ‘nation’ is synonymous with this political structure and that is where Stalin becomes pertinent.

There is a sense to be got from the climax that although Stalin is nominally in charge, the structures of repression are independent. Stalin himself is abridged to a bad odor deposited on Klenski’s hands but the structures remain intact. Later, Klenski is an ordinary man asleep on an upper berth of a train heading out across Russia and his right arm hangs out; a fellow traveler sniffs enquiringly at the hand without suspecting that the odor is the residue of the Father of the Nation. There was a sense in the late Stalin period that the dictator was the Nation and the ultimate accusation – plotting to kill Stalin was not simply intent to murder but high treason. This being the case, there is a suggestion in Stalin’s residual odor of the ‘evaporating Nation’ because all that remains of it is empty structure.

At the conclusion of Khrustalev, My Car! Klenski is in the same compartment as the stoker who is arrested in the first scene of the film and the stoker has learnt the English language. He has not yet learned the swear words but he knows the word ‘liberty’. This suggests that the absence of nationhood in the film may also be pertinent to the Yeltsin era and its American orientation, when the Soviet identity assiduously cultivated for over seven decades ended. If this reading is allowed, Khrustalev, My Car! is marking the conclusion of Soviet cinema.

Conclusion

If there is one attribute by which German’s films stand alone in cinema, it lies in his use of choreography. To reiterate what was said about choreography in The Development of Form in Soviet/ Russian Cinema, choreography in Soviet cinema treated the human body as a machine and, stated differently, this means that movement does not stem from the individual as happens in the Hollywood musical, which also uses choreography although of a different sort. In the Soviet cinema of the 1920s choreography and movement depend on montage and the cut. In later cinema – even in the 1950s with films like Kalatozov’s The Cranes are Flying, montage has made way for the tracking camera and deep focus. But the difference between the later cinema and that of the 1920s is primarily that choreography in the later cinema is used to affirm the Soviet identity, which is still elusive in 1920s cinema. In 1920s cinema (Pudovkin’s Mother was cited) montage cannot conceal the fact that the characters respond to each other from different planes, as it were. There is no sense of people making the reassuring eye contact with each other that later cinema provides and it is as if a society with a single political aim is only being assembled.

From the 1930s onwards, with the stricter ideological role assumed by cinema and the creation of the Soviet identity, cinema is ‘plane polarized’ as it were and everyone transacts on the same plane of understanding. German’s first independent effort Trial of the Road can also be described in this way although it is thematically daring for being a war film about a Soviet deserter to the enemy side. As already indicated in The Development of Form in Soviet/ Russian Cinema, the Brezhnev era – with its stagnation – was the period in which utopian discourse weakened in the public space. The arts still flourished but invisibly and, being a period for dissidence (18), the era engendered cinema which departed from the favored ideological models although it was often clumsily suppressed. The ‘difficult’ film was, essentially, a product of the stagnation period under Brezhnev and its ‘difficulty’ was associated with polyphony – because the authoritative discourse of Stalinist doctrine found it increasingly difficult to contain manifold expression.

From Twenty Days without War onwards, there is growing polyphony in German’s films. Instead of merely adopting a ‘critical attitude’ towards the state, it is as if cinema is breaking free of ideology. This last remark needs clarification: it is believed in the democratic West that being disenchanted with the communist state is synonymous with welcoming democracy but that is perhaps closer to exchanging one ideology for another. The growing polyphony in German’s films – culminating in the visual excess of Khrustalev, My Car! – is indicative of ideology being abandoned, if that is possible. It deals with dark times but is almost buoyant in tone and if it is a hellish vision of the Stalin era, it is grounded in the anarchic present; its buoyancy is ‘carnivalesque’ rather than satirical (19).

I will conclude this essay with speculation on what choreography means to Aleksei German, why he uses the tracking camera and deep focus so pointedly instead of montage to accommodate the polyphony. Choreography is evidently at the center of German’s craft and movement in his films is a deliberate effort to subvert the teleology of the narrative. Teleology can be equated with authorial narration and it would be inconsistent for a film which celebrates the carnivalesque to allow its varied elements to submit to authorial narration. Regarding his eschewing of montage, German’s cinema is a painstakingly realist cinema. In attempting to recreate ‘history’ with personal memory as its basis instead of ‘fact’, he is essentially subverting Marxist-Leninist or Stalinist historicism. This demands a realist cinema since, going by Andre Bazin’s formulations, montage is not realist but ‘expressionist’ – and ‘personal expression’ was perhaps what Aleksei German did not want his films to remain.

Notes/references

| 1. |

Giovanni Buttafava, Alexei German, or the Form of Courage, from Anna Lawton (ed.), The Red Screen: Politics, Society, Art in Soviet Cinema, London: Routledge, 1992, p 275. |

| 2. |

Nancy Condee, The Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema, New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp194-200. |

| 3. |

By the end of Stalin’s life, he had become paranoid and had had most of his former confidants executed. Beria made use of this opportunity to place his own men in Stalin’s household and Khrustalev was one of them. Beria was almost certain that he would assume power but Krushchev aligned with Malenkov had him deposed and executed in December 1953. |

| 4. |

David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film, London: Methuen, 1985, p157. |

| 5. |

David Bordwell, The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice, from Leo Braudy, Marshall Cohen (Eds.), Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings (Fifth Edition), New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, pp 717-22. |

| 6. |

This is very much as happens in a flashback in a classical Hollywood film. See David Bordwell, The Classical Hollywood Style, from David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, pp 42-43. |

| 7. |

It has been noted that Soviet filmmakers were often evaluated in the West by their ‘courage’. See Giovanni Buttafava, Alexei German or the Form of Courage, from Anna Lawton (ed.) The Red Screen: Politics, Society, Art in Soviet Cinema, p 276. I have already tried to show in my examination of Tarkovsky’s Mirror that complete opposition to state repression was not the most logically moral position for a filmmaker to take and the Soviet citizen’s feelings were more ambivalent than might have been imagined because of their own ancestors probably having been implicated in Leninism and then Stalinism. This has been articulated in a different way: “How are we to retell our history without disgracing our forefathers?” See Tony Wood, Time Unfrozen: The Films of Aleksei German, New Left Review 7, January–February 2001, p103. |

| 8. |

Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) is considered a ‘courageous’ Soviet film but it is still heroic in many of its passages. |

| 9. |

Nancy Condee, The Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema, pp 201-2. |

| 10. |

For instance see Sudipta Kaviraj, Imaginary Institution of India, Subaltern Studies 7, 1992, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp 1-39. |

| 11. |

Leon Trotsky, responding to whether history was entirely decided by class struggle and whether accidents could never play a decisive part, proposed that the effects of accidents, though individually important, were ultimately eliminated through their ‘natural selection’. |

| 12. |

Mikhail Bakhtin, Discourse in the Novel, from Mikhail Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, (Ed) Michael Holquist, trans. Caryl Emerson, Michael Holquist, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981, p 283. |

| 13. |

German regards Fellini as ‘cinema’s only realist.’ Interview in Iskusstvo kino, 8, 2000, p. 12. Cited by Tony Wood, Time Unfrozen: The Films of Aleksei German, New Left Review 7, January-February 2001. |

| 14. |

Nancy Condee, The Imperial Trace: Recent Russian Cinema, p 194. |

| 15. |

If war concludes as defeat as it did for Germany in 1945, domesticity cannot evidently resume as seen in its films – e.g. Helma Sanders-Brahms’ Germany Pale Mother (1980). |

| 16. |

There are evidently other approaches which are possible. Another course is a fictional investigation into an event from a later perspective and an example is Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Stratagem (1970). This approach appears to turn the enquiry into a personal quest or discovery and there is a deliberate blurring of the truth behind the event being investigated. |

| 17. |

After Schindler’s List (1993) swept the Academy Awards the editorials and commentaries made implicit and explicit connections between the film and concerns about the state of Israel, about conflicts between Israelis and Arabs, and about anti-Semitic statements by members of the African-American community. See Marcia Landy, Cinematic Uses of the Past, Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1997, p 256. |

| 18. |

Alexander Timofeevsky, The Last Romantics, from Michael Brashinsky and Andrew Horton (eds.), Russian Critics on the Cinema of Glasnost, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp 28-9. |

| 19. |

The ‘unfunnyness’ of its ‘satire’ was noted by The Guardian. Ronald Bergan, Aleksei German obituary, The Guardian dated 21st February 2013. |

MK Raghavendra is the Founder-Editor of Phalanx

Courtesy: static.guim.co.uk

Courtesy: s3.amazonaws.com

Courtesy: filmlinc.com

Courtesy: s3.amazonaws.com

Courtesy: seagullfilms.com

Courtesy: wfiles.brothersoft.com

Courtesy: olivierpere.files.wordpress.com

Courtesy: farm1.static.flickr.com

Courtesy: www.dvdbeaver.com

Courtesy: farm1.static.flickr.com

|

|