|

I

The Sahitya Akademi seminar, where a version of this paper was presented, was on the survival of the vernaculars of India’s eastern regions in the age of globalization. The concept note seemed straightforward enough. Perhaps, it was too straight, simple. It did not, for instance, spell out the implications of the word ‘survival’. Evidently, the implication was that there were threats or challenges faced by the vernacular or to use a current term bhasha literatures. What were these threats that endangered Indian languages? How directly were they linked to the phenomenon of globalization? Were the many Indian bhasha literatures fighting an unequal and thus losing battle against the onslaught of English? There were questions which lurked like shadowy monsters beneath the depths of a placid lake.

It was an impressive congregation of linguists, scholars of language and culture, and eminent authors—writers of fiction and poetry. Two major issues emerged from these discussions: the hegemony of the English language especially as it pertains to pedagogy or learning—one whose dominance seems to be directly proportional to the economy and politics of globalization and the aversion to print culture and the neglect of engagement with print culture—the deeply moving accounts of books lying neglected in libraries. The present generation seemed engrossed only in the visual and aural world of cyberspace which they could access at the tap of a finger.

As I mulled over the day’s proceedings it struck me that we had amassed a wealth of facts and figures about the languages of the eastern region of our country - the histories of their existence, the various crises against which they struggled, and the proffered opinions and solutions for survival of the linguistic communities. Missing were the accounts of the precious personal links with the language of the communities we were born into. If language was ‘human, all too human’ then that quality could not be fathomed solely through socio-linguistic, or philological or economic and may be ethnographic modes of studying linguistic communities in the abstract. Surely, we all had our own narratives about our changing relation to our languages; fascinating stories which needed to be shared and recorded. It was my belief that what would emerge--- like the project of reading biography as historical evidence, could constitute a new historiography of how languages survive.

Thus instead of a socio-linguistic summary of how Bengali has coped with the challenge of English in the age of globalization I offer myself as the subject of this critical historical gaze, using biography and reminiscence as a valid mode of inquiry. Let me begin, therefore with an anecdote. I have great faith in anecdotes as bearers of truth; they encapsulate like metaphors, several elements of a complex issue, like the one this seminar has proposed. So let me begin with one:

It was a sultry August morning at the Howrah Station when I was accosted by my colleague from the Philosophy Department. After we had exchanged the usual pleasantries she said, ‘I have begun reading your novella.’ I felt deeply gratified and waited eagerly for further comment. She paused, ‘I was quite amazed you know’ she said ‘that you had written a Bangla novel!’ I was taken aback at this strange response. My colleague went on blithely, ‘It’s kind of strange for someone like you to write fiction in Bangla,’ she said in a well-meaning way. I was nonplussed. ‘Someone like me? Whatever does that mean?’ I blurted out almost involuntarily. She smiled and then gesticulated in a meaningful way to indicate that I didn’t quite fit the bill of a bona-fide Bengali author. ‘Why don’t you write your next novel in English,’ she suggested as she patted my shoulder in a patronizing way, ‘maybe it will make you both rich and famous’ she added with a chuckle. On that note we parted ways on the platform. I boarded the train and spent the journey from Kolkata to Santiniketan musing on this encounter as the train hurtled through the familiar landscape.

This anecdote is double edged: on the one hand it suggests that there is a binary within the Bengali linguistic community itself at least in popular perception – the ‘true’ or authentic inheritors of the Bengali language and literature and the ‘imposters’ the interlopers— in my colleague’s opinion I belonged clearly to the latter and second as the imposter ‘ Bengali’ with a privileged access to English, I had an edge over the ‘authentic’ since I could write an English novella and be part of a global community of writers.

Evidently there is a certain popular psycho-social understanding of the hierarchy of the two languages – Bengali and English in our times. While the roots of this unequal power relation can be traced to the 19th century, the consolidation of colonial modernity in India, its branched ramifications in the globalized world has a different story to tell. In what follows, I shall attempt to trace this trajectory, albeit in a cursory manner by scrutinizing, and ‘problematizing’ the assumptions that underlie my colleague’s comments; and in the process my method will be to focus on myself as the figure of the bi-lingual Bengali as opposed to the image of the anglicized Bengali that my colleague evoked.

So let me go back to the reminiscence mode and the train journey where I reflected on what my colleague meant as someone of my kind. The disparaging even racist term for such a person, current in our youth was ‘tnyash phiringi.’ The derogatory Bengali phrase could be decoded as an anglicized person, a product of colonial English education. The claims to ‘modernity’ of such a being lay in a fashionable amnesia and indeed contempt of one’s first language /mother tongue and the Bengali culture. This manifested itself in a rejection of the literatures and cultures of the linguistic community as unsophisticated and an uncritical embracing of all that was ‘English.’

The ‘anglicized Bengali’ was perhaps an exaggeration or caricature of certain visible ‘real’ symptoms in the subjects. Unfortunately, it failed to register that there were variations within the original prototype. This was primarily due to personal interventions happening at a familial level which modified the type, creating different forms of the hybrid. I will offer my case as an instance. Thus, while it is true that my middle class parents ( both of them were professionals) in all their wisdom decided to send me to had an ‘English medium, missionary school’ because it happened to be the only decent one within an hour’s bus-ride, they were not anglicized themselves. However, they had had benefited from a colonial education system, which taught them the English language which allowed them access to various forms of profession. They did not feel the need to monitor my learning or were not overtly concerned with the effects of this education.

However, my maternal grandmother, who played a significant role in my upbringing, felt that it was crucial to counter the damaging ‘foreign’ influence. Her preferred mode was by giving me a taste of the Bengali language classics. She was in many ways a remarkably unconventional woman: a deeply spiritual but non-orthodox Brahmin widow, she had no formal education and was self-taught. Perhaps because of that her interest was not restricted to ‘religious texts’ but included novels, romances, social histories, plays and poetry. So I read avidly, even before I reached adolescence, without any idea of the history of Bengali literature, Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, Dwijendralal Roy, Michael Madhusudan Dutta, Anurupa Devi, Ashapurna Devi, Saradindu Bandopadhyay, Rajshekhar Basu and Saratchandra. These were the writers who had fired

her imagination and I had been chosen as the inheritor of her library. Curiously missing from this pantheon was Rabindranath Tagore, whom I discovered much later and with whose writings, I developed an entirely different critical mode. I not only thrived on the content of the fiction but imbibed ever so unconsciously the linguistic registers, so that when I began to write in Bengali by the time I was in my mid twenties, my writing became, to use Roland Barthes’ terms, ‘a tissue of quotation’ ( not to be confused with plagiarism).

|

My point in recounting this biographical detail is that contrary to my colleague’s impression—thanks perhaps to my glib articulations in English – I was and still remain not an instance of an anglicized but what I would like to re-categorize as a ‘bi-lingual Bengali.’ I am not suggesting for once that mine is an exceptional case-it was only when I went to study at the English Department of a prestigious university that I found many of my ilk. The trajectories of our engagement with the two languages may have had different narratives but there was even in the mid 80s, middle class youth who did not feel the need to, as in erotic affairs, sever relations with one language in order to establish intimacies with another.

We were still in touch with history, albeit a colonial |

one. Bengal had reaped the benefits of a two-way traffic that that existed between English and the Bengali; two of Bengal’s major writers, Michael Madhusudan Dutt and Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya began their creative writing careers in English. In both cases these attempts turned out to be failures; it was only then that Madhusudan and Bankim turned to Bengali. The return of the prodigal sons was a happy occasion because they brought to their learning in European languages and in the process gave a fresh lease of life to Bengali literature.

II

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, whose first novel Rajmohan’s Wife sank without a trace advised young men like Romesh Chandra, ‘You will never live by your writing in English…. Govind Chandra and Sashi Chandra’s English poems will never live, Madhusudan’s Bengali poetry will live as long as the Bengali language will live.’( 1) Dutt had himself went on to record this in his famous sonnet (included now in almost Bengali school textbook anthologies) in which he lamented his own ignorance and folly in his inability to recognize the rich jewels of Bangla and covet the goods of the English language like a beggar. But this celebration of the mother tongue as the vehicle of creative writing was by no means an insular or chauvinistic/ parochial tendency. Even if we leave aside the genius of Tagore who embraced internationalism as the credo in his writing, philosophy and pedagogical innovations the bourgeois Bengali in the post-independence era had always operated in two worlds, the world of English/Europe and Bangla.

Indeed in the 1940s and`50s Bengali intellectuals and writer-critics like Buddhadev Bose, Bishnu Dey, Sudhindranath Dutta, Samar Sen were not only formidable scholars of English and European literature but were prolific translators of English and European works especially modernist and symbolist poetry into Bangla. One could definitely include in this list Leela Majumdar and Mahasweta Devi both of whom studied English as their formal disciplines but went on to write in Bengali. This traffic from the west through translation not only of texts but critical thinking played a significant role in setting the trends of post–Tagore Bangla literature. As an undergraduate student I had the privilege of being taught by poets like Pranabendu Dasguta or Jagganath Chakrabarty who had gained an iconic status. Manabendra Bandopadhya, associated so closely with the Sahitya Academy was a prolific translator who had brought home the treasures of Latin American writing in Bengali.

This bi-lingualism has lamentably been lost. Barring the case of writers of critical prose/essay, this trend of creative bi-lingualism is largely on the wane. This is largely an urban phenomenon. There is an attendant malaise amongst the middle-class educated younger generation of Bengalis who affect a disdain for Bengali literature and language. This phenomenon of the mono-lingual Bengali—restricted either to Bengali or English or sometimes a strange hybrid chutinified form of language is a later phenomena, one which coincided with economic liberalization and with the phenomena of globalization. While I am not equipped to comment on the impact of globalization on bhasha literatures in India it seems to me that the linguistic community is gradually beginning to lose faith in Bengali, which is fighting an unequal battle with English. The reasons are evidently social and economic, with English operating as the language of power/knowledge not merely in already established preferred disciplines but also in the growing service sectors—epitomized by the Business Process Organizations, which employ large number of the youth.

My focus with the persistence of the hegemony of English in the erstwhile colonies, indeed its rise in prestige after formal and political decolonization is concerned also with its cultural ramifications. As Aijaz Ahmed points out

India has numerically by far the largest professional petty bourgeoisie, fully consolidated as a distinct social entity and sophisticated enough in its claim to English culture for it aspire to have its own writers, publishing houses, and a fully fledged home market for English books.(2)

Michael Madhusadan Dutt’s desire to dream in English may have ended in despair but we now have among Bengali quite a few who have made their mark, as he ‘new makers of World fiction.’(3)They are a generation of writers who reap the benefits of a globalized economy. Recipients not only of prestigious literary awards they often make headlines with whooping sums of advance that they have received from their publishers. These writers, primarily from the diaspora, enjoy a power and prominence in the world literary market unimagined by those who wrote fiction in English in the 30s or 60s. Tracing the contours of this difference is outside the purview of this discussion and I mention global image of the English language writer from postcolonial nations because it has had a strange effect on those writing in bhashas.

In his introduction to the Vintage Book of Indian Writing (1947-1997) which no doubt serves as an authoritative and representative volume of Indian writing to the Western metropolitan reader,

|

Salman Rushdie champions the cause of ‘English-language Indian writing’ in a manner that would have made Thomas Babington Macaulay proud. Indian writing in English, states Rushdie is proving to be a stronger and more important body of work than most of what has been produced in the 16 ‘official languages’ of India, the so-called ‘vernacular languages’ during the same time; and indeed this new and still burgeoning ‘Indo-Anglian’ literature represents perhaps the most valuable contribution India has yet made to the world of books. (4)

The entry into the global English literary market with its system of literary agents, prestigious publishing houses with commissioning editors apparently head-hunting for new talents seems to be a much more favourable option than bending in supplication to Bengali publishers who seem to go by name or recommendations. There has been a significant |

rise of these journals and magazines in the Bengali public sphere suggesting that the term ‘little’ affixed to the

magazines is clearly an ironic misnomer for they appear to be the Olympians gods. While it may be true that the circulation of such journals is limited to a coterie, as indeed its writer’s list, but it is the privilege of being published in these that count as the sign of having arrived as a Bengali author.

Publishers informed me that the Bengali readership was interested only in one genre of writing viz. the serious essay. This is linked, however tangentially, with the fate of what we consider one of the major modes of expression of the Bengali language-prose fiction and poetry, the two genres which had both a popular and an intellectual appeal. If the contemporary Bengali language reader is not interested in these genres, then what would be the fate of such writers? I was told, in spite of having published consistently in literary or ‘women’s magazines’ for over 20 years, that I was a ‘new’ writer in the market. The market, the taste of the large number of contemporary readers, is in fact determined by the policies of a few corporate publishing houses. So, the urban Bengali is now fed only with a certain kind of fiction—one in which the language is a close verisimilitude of what is spoken, and heard, a variety of hybrid which is also a marker of class in a globalised economy . Thus, it seems certain narratives, those of the large population especially those living in the margins, villages and border towns are getting lost. Their voices, the language which they speak is fast vanishing from the world of Bengali print culture.

III

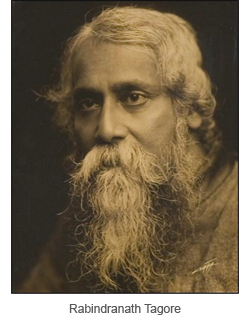

The loss of the narratives of people from the margins, the celebration of a consumerist market–driven urban modernity would have deeply distressed Rabindranath Tagore, the most famous Bengali author of all times. Yet, Rabindranath too did not wish to confine his identity as a Bengali writer. Bilingualism for Tagore came via translations. Rabindranath Tagore, the first Asian to be

|

awarded the Nobel Prize exactly a hundred years ago, was recognized as a major poet on the basis of the English translation of his poems done by himself. In the third part of my reflections I turn to focus on the ‘English career’ of Rabindranath Tagore, tracing its trajectory for a brief period of five years ( 1912-1917). I would suggest that his unique bilingualism— he translated his own poems and also delivered lectures and wrote essays in original English, became, happily for him, the twin modes through which he fashioned different facets of his personality.

Tagore’s Bengali readers are familiar with the notion that the Gitanjali poems were translated from the Bengali verses in a wholly casual, spontaneous way.

In his letter to his favourite niece, Indira Devi, Rabindranath had evoked a vivid image of the lazy, langorous early summer of 1912, redolent with the |

smell of mango blossoms, when he began to translate his own poems into English, as he was recuperating. While the incident itself may not be construed, scholars have found enough evidence to suggest that Tagore’s efforts at translation were not entirely unpremeditated. He began to articulate a growing need to reach out to an Anglo-phone world from the second decade of the twentieth century. In May 1912, in a letter to Manoranjan Bandopadhyay he wrote, ‘People across the sea want me now – I have my place there among them’(5). Tagore was evidently referring to his hope of disseminating his writings through their English translations. In retrospect the letter seems almost prophetic. The English Gitanjali was published in November 1912 and the award of the Nobel prize followed in November 1913. Rabindranath Tagore had not only found his place among people and cultures across the sea but also emerged as the poet-sage from the Orient whose Romantic-mystic lyrics and verses even in their prose translations, provided solace to his many Western readers in the hours of spiritual desolation, the dark night of the soul.

Though he translated the poems himself, he left the translation of his short stories, novels and plays to his friends and admirers. Many of these short fictions were published in The Modern Review , edited by Ramananda Chattopadhaya; this prestigious literary magazine enjoyed a circulation amongst the elite readers in England. After the award of the Nobel Prize there was a constant demand for English translation of his fictions. A cursory glance at the English publication of his writings between 1913 and 1922, include seven anthologies of poetry, four anthologies of short stories, nine plays, and one novel.(6)

Curiously enough there wasn’t much initiative to translate his Bengali essays. One reason for this could be that from 1913 onwards Rabindranath began to deliver public lectures in English especially during his tours both within India and abroad which were later published as essays and anthologized. The following is a list of such anthologies of English essays published within this ten year period: Sadhana (1914), Personality (1917), Nationalism ( 1917), and Creative Unity (1922). The Centre of Indian Culture published in (1919) is a long essay originally delivered as a convocation address in Anne Besant University Adyar, Madras.

In his letters to his friends and admirers, Rabindranath often complained of being exhausted by this demand; it is likely he also enjoyed this new role which added a different and distinctive dimension to his English career and his personality. Rabindranath’s English addresses and lectures may be attributed to his growing importance in the public sphere in the West, as a celebrity speaker. Confident in his awareness of his Western audience and reading public, Rabindranath was instrumental in a certain self-Orientalization and fashioned a somewhat limited English speaking-writing persona. The general sweep of these English essays creates the impression of a solemn philosopher-preacher making generalized, abstract pronouncements.

Fortunately for us this is not the entire English Tagore. It is worth remembering that the Nationalism essays (1917) also belong to this period. Though these essays owe their origin to invited public lectures delivered in Japan and America in 1916, when the First World War was in full swing, they are not ‘occasional.’ Though Rabindranath Tagore has never been regarded as a political thinker, it is evident from the Nationalism essays that he did ponder and pronounce upon the most crucial political developments of his times. Perhaps, the real significance of the Nationalism essays lie in their astute analysis of the symbiotic relation between various organizations or systems of power—that of nationalism, capitalism and colonialism.

These essays merge polemic with poetry. Nations are characterized as gigantic factories in which the ‘national machinery of commerce and politics turns out neatly compressed bales of humanity which have their use and high market value;’(7) it is this industrial mass production of human beings that devalues individuality and is intolerant of difference; it is full of ‘carnivorous and cannibalistic’ tendencies and feeds ‘upon the resources of other peoples’ trying to swallow their whole future’ and this colonial logic is related intimately with xenophobia, creating a political civilization that is ‘based upon exclusiveness’ and ‘watchful to keep the aliens at bay or to exterminate them.’(8) But perhaps the most moving image that uses to evoke the terror of nationalism in that of predatory ‘hounding wolves of the modern era, scenting human blood and howling to the skies.’(9)

It may be difficult to make a case for a truly bilingual Tagore since the major portion of his prolific output is in Bengali. Yet, till the very end he felt the need for a certain bilingual identity to communicate to a larger global audience, his own introspections, musings, and warnings. It is this that compelled him to arrange for a translation of his Bengali essay ‘Sabhyatar Sankat’ (1941) into English as ‘Crisis in Civilization.’ Tagore did not live to witness the effects of globalization but he had experienced the two World Wars, and sensed that human kind had initiated a process of self-destruction which would inevitably hurtle civilization to an end. In the face of such terror he continually evoked the need for an alternative global community, an audience to which he could speak only in English.

Thus we see that the relationship between English and Bangla has been a productive one for many writers. This being the case it may be interesting to ask why, in the global age, a writer is being asked to choose one language over the other. The easiest answer is that English fiction has acquired glamour but there must be more than just that. Since the fiction published in Bangla is written in a prose arguably close to that spoken in Kolkata – and without the traces of other dialects which once enriched Bangla fiction – it may be conjectured that fiction is now entirely a receptacle of the global – as English fiction has itself perhaps come to be. Needless to add, the development will certainly restrict the experiences that bhasha fiction can give expression to. Perhaps, in the ultimate analysis, Bangla fiction will be no different from English language fiction in India since neither will be marked by the histories of the two languages and will only give expression to the everyday experiences of the same class in the process of conducting business in the globalised metropolis. The resulting sameness in what the two languages express may be why bi-lingualism is gradually being driven out of Bangla literature.

Notes/references: Notes/references:

| 1. |

Meenakshi Mukherjee, The Perishable Empire, (New Delhi: OUP. 2000) p.47. |

| 2. |

Aijaz Ahmad, In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures, New Delhi: Oxford, 1994, p.75. |

| 3. |

Pico Ayer ‘The Empire Writes Back’, Time, 8 February 1993, pp 46-56. |

| 4. |

Salman Rushdie and Elizabeth West (eds.) The Vintage Book of Indian Writing, 1947-1997( Vintage Books, 1997)p x. |

| 5. |

Quoted in Bikash Chakravarti. ‘Twice Born? A Note on Tagore’s English Career’ in Pranati Dutta Gupta, and Susmita Ray eds Indian Writing in English: Yesterday Today and Tomorrow . Kolkata: Vivekananda College,2006. pp. 61-69, p.62 |

| 6. |

Anthologies of poetry include, apart from Gitanjali, The Gardnener, The Crescent Moon, FruitGathering, Stray Birds, Lover’s Gift and Crossing; the plays which were translated include Chitra The King of the Dark Chamber, The Post Office, The Maharanis of Arakan, Sacrifice and Other Plays, The Cycle of Spring, Autumn Festival, The Trial, The Waterfall; the anthologies of short stories translated almost entirely by others: Glimpses of Bengal Life, Hungry Stones and Other Stories, Mashi and Other Stories, Stories from Tagore, The Parrot’s Training ( single story). The novel is The Home and the World. |

| 7. |

Rabindranath Tagore ‘Nationalism in the West’ in Ramachandra Guha ( ed) Nationalism . NewDelhi: Penguin, 2009. p 35. |

| 8. |

Ibid ‘Nationalism in Japan’ p.8 |

| 9. |

Ibid. p. 32 |

Swati Ganguly got her PhD from Jadavpur University. She is Associate Professor in English, Department of English and Other Modern European Languages, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan. She has worked extensively in the area of Renaissance, feminism, gender studies as well as on media issues. She also writes fiction in Bengali.

Courtesy: devarshi.faithweb.com

Courtesy: blogs.worldbank.org

Courtesy: tripura4u.com

|

|