|

|

|

|

Some questions about microfinance and self-help groups

The editorial examines how self-help groups and microfinance may not be what they were once intended to be – the silver bullet to eliminate poverty – and this could soon become a case of the cure being worse than the disease.

Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Responses to the Editorial in Phalanx 4

Why Does the Anglophone Indian want to be a Novelist?

Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

Films: |

|

|

Avatar

by James Cameron

Read Read |

|

|

3 Idiots

by Rajkumar Hirani Read Read |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Home > Contents > Article: M. K. Raghavendra |

|

|

Nation and Transgression

Ideology and the Horror Film in India and Pakistan

M. K. Raghavendra

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Horror as a transgressive mode

Horror, at least after pornography, is perhaps the least reputable among all categories of film. The emotions it deals with are often tied up intimately to the body – rather than to the mind or the soul and these might be understood as unpleasant – fear, disgust and revulsion. Yet, there is a huge appetite for horror which continues even when other popular genres in cinema have lost their attraction. One of the key elements in most horror films is the ‘monster’ – the horrific or repulsive object that no horror film can do without. Examples for the monster range from Regan in The Exorcist (1973) to Jason in Friday the 13th (1980) and Freddy Krueger in Nightmare on Elm Street (1984).  Among the explanations offered for the place of the monster, the most tenable one is that it is not its appearance that the audience finds most attractive but the narrative around it, i.e. the curiosity aroused by the ‘impossible’ and its fulfillment in the monster. Where a disaster film arouses curiosity about an unknown experience, an asteroid crashing into earth, a volcano under New York, the horror film arouses curiosity about the impossible, possession by the devil or a man-eating alien. The disgust aroused by the object at the heart of the horror film is therefore not craved for by the audience as an emotion but is only a predictable concomitant of satisfying the curiosity aroused (1). The revulsion is simply attendant to our being made to believe in the impossibility of the occurrence. To use a helpful analogy, the bitterness of the pill perhaps induces belief in an impossible ailment. Among the explanations offered for the place of the monster, the most tenable one is that it is not its appearance that the audience finds most attractive but the narrative around it, i.e. the curiosity aroused by the ‘impossible’ and its fulfillment in the monster. Where a disaster film arouses curiosity about an unknown experience, an asteroid crashing into earth, a volcano under New York, the horror film arouses curiosity about the impossible, possession by the devil or a man-eating alien. The disgust aroused by the object at the heart of the horror film is therefore not craved for by the audience as an emotion but is only a predictable concomitant of satisfying the curiosity aroused (1). The revulsion is simply attendant to our being made to believe in the impossibility of the occurrence. To use a helpful analogy, the bitterness of the pill perhaps induces belief in an impossible ailment.

The ‘impossibility’ at the heart of the horror film does not however mean that the films are necessarily ‘fantastic’. Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), for instance, arouses curiosity about a dead woman (Norman Bates’ mother) coming alive and the impossibility of the occurrence finds manifestation in the climax in the fruit cellar when the protagonists (and the audience) discover the ‘monster’ – ‘Mrs Bates’ mummified corpse turning around in its chair, its eye sockets empty but the swinging light overhead making it seem grotesquely alive. While a rational account follows, it does not negate the fact that, until the climax, the film has toyed with the ‘impossible’ and planted an occult explanation in our minds.

‘Horror’ is perhaps not a ‘genre’ in the sense that it is not bound to the conventions of a given age. Like some other ‘modes’, it exists across a whole range of historical periods, offering itself, if only intermittently, as a formal possibility which can be revived or renewed (2). This may explain why it frequently occurs as an element combining with recognizable genres – like SF (Alien, 1979) the teen film (Nightmare on Elm Street, 1984) and the detective story (The Silence of the Lambs, 1991). In the process, the effect of the horrific element inserted into a genre film is transformatory, sometimes even subversive. Where SF is often optimistic (as in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968) the SF-horror film is dark. Where the whodunit celebrates the triumph of science and the rational, the detective in The Silence of the Lambs uses the assistance of a dangerous lunatic. This, it can be argued, opens out the story to possibilities beyond those offered by the normal detective story.

It is perhaps this ‘subversive’ side of the horrific element that makes the horror film ‘political’ in some sense because popular genres in cinema are often vehicles for the dominant ideology. It has, for instance, been noted that horror films are often engaged in an unprecedented assault on all that bourgeois culture is supposed to cherish – like the ‘ideological apparatus’ of the family and the school( 3) and films like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) have been celebrated for their adversarial relat ion to contemporary culture and society. In this film, a family of men, driven out of the slaughterhouse business by advanced technology, turns to cannibalism. This has been interpreted as embodying both a critique of capitalism, since it shows people quite literally living off other people, and of the institution of the family since it implies that the monster is the family (4). ion to contemporary culture and society. In this film, a family of men, driven out of the slaughterhouse business by advanced technology, turns to cannibalism. This has been interpreted as embodying both a critique of capitalism, since it shows people quite literally living off other people, and of the institution of the family since it implies that the monster is the family (4).

Even if such an overtly political reading is not allowed, there is still little doubt that the horror film offers something vividly scandalous and transgressive to the audience. It has been found, for instance, that mail order video companies bracket cult horror with European art cinema, much of which-like the films of Luis Buñuel and Jean-Luc Godard – is formally bizarre and unashamedly ventures into disreputable terrain (5). If mainstream cinema is ideologically coercive, it can be argued that the transgressions of the horror film like those of art cinema offer respite and are therefore adversarial in a politically distinct way.

If this political function is granted, the dominant form taken by horror in cinema in any period also helps one identify the kind of ideological coercion it is aligned against. To illustrate, the kind of horror film most popular in the United States in the past decade or two may be teen horror. If the teen film is the genre into which the horrific element is inserted it will be interesting to look at the conventions of the teen film. The codes and conventions of the teen film genre vary depending on the cultural context of the film, but they can include proms, alcohol, illegal substances, high-school, parties and all-night raves, losing one's virginity, relationships and rivalries, social groups and cliques and American pop-culture. A characteristic of the youth film is that adults constitute a separate group kept apart to enforce the sense that young people are ‘rebels’, or at least breaking with an older generation – instead of inheriting its attitudes. The reason is perhaps that the teen film does not simply have young people as its subject but also targets them. The ‘break’ with the parents in the teen film may be a way of making the targeting more effective by keeping the space of the narrative excluded to the older generation. It is this ‘exclusivity’ of the narrative space that enables the teen film to parody ‘adult’ notions like patriotism (as in Grease 2, 1982) without the films incorporating radical political discourse.

While there is an apparent journey towards monogamous heterosexuality with a suggestion of future family formation in teen films, more important is perhaps the sense to be derived from them that that they celebrate youth and health. If the ‘inner body’ refers to the maintenance of the body, its protection from disease, abuse and deterioration, the ‘outer body’ refers to the appearance and the employment of the body within social space. Consumer culture – with advertising at its helm – has, in the past few decades, increasingly focused on the young outer body as a vehicle for self-expression, achievement and pleasure. Images of the body beautiful, openly sexual and associated with hedonism, leisure and display, emphasize the importance of appearance and the ‘look’ (6).

It is this context that films like Friday the 13th, Nightmare on Elm Street and I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997) are significant. All these are ‘slasher’ films in which a group of young people are attacked one by one and done to gruesome death usually by someone unknown. Where the teen film focuses on the young body as an object of envy or desire, these films try to create uneasiness around it. The object of fetish in the teen film is deliberately dismembered – sometimes dwelling with relish on the mutilation. Another important aspect is that where the teen films try to exclude the older generation from the narrative space, these films are about the difficulty of such exclusion. In Nightmare on Elm Street the young people are killed by the ghost of a man who was burned alive by mothers after he was acquitted in court on the charge of murdering children. In the other two films, young people, in their eagerness to have fun, were responsible for deaths, and the killings revolve around the dead person, or an agent, getting vengeance. There is, therefore, the sense that the sins of the past are inherited by the young.

While the films just cited try to create uneasiness around the young body, most of them are too timid to venture into truly ‘disreputable’ terrain. They try to compensate for their tentativeness through sudden violence. But to rely on the analogy used earlier, the ‘bitterness of the pill’ may make the impossible ailment believable but it does not guarantee the unease from it, and the teen horror film has, increasingly, been domesticated. To provide a more successful instance of the creation of unease, David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) draws from both horror and pornography in its subversion of teen film convention  and ventures boldly into disreputable territory. Although it is not nearly as gruesome as Friday the 13th or I know what you did Last Summer, it is more disconcerting. This leads us to suspect that it is only cult cinema in which one can find the truly disreputable and transgressive (7). The popular is perhaps too much a hostage to dominant ideology for it to be adversarial. If cult cinema proceeds by extending the scope of artistic expression, popular horror films like I know what you did Last Summer even stereotype the ‘impossible’. and ventures boldly into disreputable territory. Although it is not nearly as gruesome as Friday the 13th or I know what you did Last Summer, it is more disconcerting. This leads us to suspect that it is only cult cinema in which one can find the truly disreputable and transgressive (7). The popular is perhaps too much a hostage to dominant ideology for it to be adversarial. If cult cinema proceeds by extending the scope of artistic expression, popular horror films like I know what you did Last Summer even stereotype the ‘impossible’.

The Indian Nation and the horror film

If ‘America’ is inscribed in mainstream Hollywood cinema through certain cherished national values – often through the valorization of the family and the motivated individual – mainstream Hindi cinema relies on other strategies to admit the Indian Nation into its narratives. The idea of the Nation is often accompanied in this cinema by associated notions – the Land, the State and Tradition, to name a few. The State has a strong presence from the 1950s onwards and is emblemized by the police and the judiciary. The Land was perhaps notably represented when agrarian issues dominated public consciousness as in Upkaar (1969). Some of the other notions have weakened but Tradition has been the most durable among them. The favored (although not only) way of representing Tradition is for an elderly character (usually a parent) becoming a moral signpost directing or judging. When, in Deewar (1975), Vijay?s mother leaves him to live with her younger son, a police officer, the discourse is partly that Tradition is aligned with the State.

The ‘Community’ is another presence in cinema but it could be a way of allegorizing the Nation since it is often given the Nation’s attributes. In Mother India (1957), the Community is the village and in Hum Aapke Hain Koun…! (1994) Kailas Nath’s family gatherings represent the Community. In Border (1998) the Community is the military while in Lagaan (2002), it is the cricket team. In each of these films the Community is constituted to include religious minorities, different castes and social classes. The Community, like the Nation, commands loyalty and betraying it or its creed merits punishment. This sanctity accorded to the Community means that it has a much greater significance than suggested by its physical constitution. To explicate, the village in Mother India is not merely an Indian village just as the cricket team in Lagaan is not merely a village cricket team. The Community as the Nation in microcosm also means that the deepest conflict in the narrative are arranged within and not caused by agencies external to it. The character(s) at the moral centre of the narrative as well as those creating discord are therefore part of the Community – as in Mother India, HAHK and Lagaan.

A characteristic of the Nation in the mainstream Hindi film is that it is ‘modern’. If the films after 1947 are frequently set in the city, the city is also an emblem of Nehruvian modernity (8). The city is not always the chosen locale and there are other motifs associated with modernity. When the farmer is the key motif modernity can be represented by dams (as in Mother India) or by mechanized farming (as in Upkaar). In the later films, doctors, colleges and industry can also serve as useful emblems of modernity. The Hindi mainstream film was once labeled ‘fantasy’ but what is important here is that occult elements (e.g. ‘magic’ and rituals associated with it) rarely feature in it. As Ashis Nandy has convincingly argued (9), the reform movements of the 19th and early 20th century consciously tried to remake India in the image of the colonizers and this explains why the mainstream film – since it addresses the post-colonial Nation – eschews the magical elements in which tradition had once been rich. Even mythology was rejected by the mainstream film in its mature years and the kind of mythological film favored was the saint film (e.g. Sant Tukaram, 1936) in which the issue is social reform (an off-shoot of modernity) rather than the gods and demons of the puranas. Devotion is allowed (10) as is reincarnation, but these are cornerstones of Hindu belief and are not 'fantastic' just as the power of faith and redemption cannot be termed 'fantastic' when we deal with Hollywood. If fantasy still flourishes in the regional popular film it is because regional cinema is not 'national' in the way that the Hindi film is and primarily addresses local identities.

In defining ‘fantasy’, Tzvetan Todorov (11 )concentrates on the response generated by the ‘fantastic’ events in the story. In this light, fantasy must be considered not just one mode but three. ‘Fantasy’ creates a situation in which the reader/audience experiences feelings of hesitation and awe provoked by strange, improbable events. If the implausibility of the events can be explained rationally or psychologically (e.g. as a dream, hallucination), then the term ‘uncanny’ is applied. In stories like Lord of the Rings, in which an alternative world or reality is created, the term ‘marvelous’ is considered most appropriate to describe the work. Going by this definition, it is largely the horror film which corresponds to ‘fantasy’ in Hindi and the genre is distinctly outside the mainstream (12).

To get a rough idea of the horror film in India, I propose to examine two films made twenty-five years apart. The first film Purana Mandir (1984) was made by Tulsi and Shyam Ramsay, who are generally associated with the horror film. The pre-title sequence in  the film is set in a bygone century in which a 'shaitaan' named Samri was running amok and attacks the princess Rupali. The king Hariman Singh's men arrest Samri and the 'shaitaan' is tried, found guilty and beheaded. At the time Samri pronounces the following curse upon the king: So long as my head is away from my body, every woman in your line shall die at childbirth; and when my head is rejoined to my body, I will arise and wipe out every living person in your dynasty. The head and the body are therefore kept apart a trishul chained to the box containing the body so that Samri does not return to life. The film then moves to the present century in which the king?s descendant Thakur Ranvir Singh (Pradeep Kumar) lives in an unnamed city. This part of the film deals with the king?s apprehension at his daughter falling in love because of Samri's curse on the family. When the daughter Suman (Aarti Gupta) who is in college learns about it, she and her boyfriend Sanjay (Monish Behl) proceed to the ancient haveli in which the 'shaitaan' Samri is still interred and appears before he is destroyed, through Lord Shiva's guidance. the film is set in a bygone century in which a 'shaitaan' named Samri was running amok and attacks the princess Rupali. The king Hariman Singh's men arrest Samri and the 'shaitaan' is tried, found guilty and beheaded. At the time Samri pronounces the following curse upon the king: So long as my head is away from my body, every woman in your line shall die at childbirth; and when my head is rejoined to my body, I will arise and wipe out every living person in your dynasty. The head and the body are therefore kept apart a trishul chained to the box containing the body so that Samri does not return to life. The film then moves to the present century in which the king?s descendant Thakur Ranvir Singh (Pradeep Kumar) lives in an unnamed city. This part of the film deals with the king?s apprehension at his daughter falling in love because of Samri's curse on the family. When the daughter Suman (Aarti Gupta) who is in college learns about it, she and her boyfriend Sanjay (Monish Behl) proceed to the ancient haveli in which the 'shaitaan' Samri is still interred and appears before he is destroyed, through Lord Shiva's guidance.

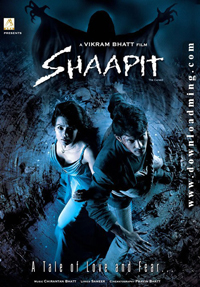

The second film Shaapit (2010) , which is directed by Vikram Bhatt, also  features a king's family and begins around 350 years ago with a curse by which any female descendant born into the family will die in an accident. The rest of the story is in the present with Kaya unable to marry Aman because of the curse. This time, however, there is a professor of the occult named Pashupathi (Rahul Dev) who assists them. The three return to the family's ancestral place and uncover a story of royal intrigue, which engendered the evil spirit in the present. Like the other film, Shaapit also ends with the monster destroyed forever. features a king's family and begins around 350 years ago with a curse by which any female descendant born into the family will die in an accident. The rest of the story is in the present with Kaya unable to marry Aman because of the curse. This time, however, there is a professor of the occult named Pashupathi (Rahul Dev) who assists them. The three return to the family's ancestral place and uncover a story of royal intrigue, which engendered the evil spirit in the present. Like the other film, Shaapit also ends with the monster destroyed forever.

While the mainstream Hindi film of the 1980s is virtually unrecognizable when one compares it with the cinema of today, the two horror films cited above are much closer to each other in their motifs. If we compare the two, both films are ‘fantasies’ in Todorov’s sense because there is an initial (though nominal) disinclination on the part of the protagonists to believe in the story of the respective curses. Both films invoke the modern: in Purana Mandir, this is confined to the lifestyles of the protagonists but Prof. Pashupathi in Shaapit is a 'scientist' and the author of several books. Pashupathi also uses a western academic vocabulary often to justify his theories. There is a sense in both films of the modern not being adequate to account for experience unless it is redefined to include the spiritual/ irrational. Thirdly, both films involve ghosts/ demons created in royal households and invoke a pre-colonial past. It is only by acknowledging the accumulated spiritual 'knowledge' of the past that the protagonists are able to combat the forces aligned against them. Attention may also be drawn to the fact that, in both films, while the evil is dealt with summarily in the pre-colonial past, the modern present appears ill-equipped to deal with it when it resurfaces.

Another factor of some importance is the film’s keeping the descendants of the erstwhile royal family – i.e. those affected by the curse – and the other folk apart as though they did not belong within the same community. While a key motif is the romantic attachment between members of the two groups, there is a residual unease at the conclusion as though a union between the two would still be hazardous. If the time line of the story traverses three hundred years or more, it is apparent that the hero and the heroine have taken different trajectories and that they are not equal within the nation and the distance between them is not a matter of one family being wealthier than the other. This is also given emphasis in Shaapit when Kaya's parents ignore Aman and hardly acknowledge his presence. There is apparently more than the curse keeping Aman and Kaya apart, the film suggests. There is, therefore, a strong sense of the nation being a heterogeneous mix and not entirely the 'community' in which differences are resolvable, as the mainstream film would have it.

The Hindi mainstream film is disinclined to deal with historical time (13) although period films with romance as the key motif (Jodhaa Akbar, 2008) or patriotic films set in the colonial past (Lagaan, 2001) are routine today. But the important fact is that there is scarcely any mainstream film which deals with the distant past and the present as part of the same linear continuum. The past referred to here is not necessarily recorded history because there are various other ways in which sense can be made of the present. Partha Chatterjee cites a puranic history of India written in the 18th century which tries to make sense of the Battle of Plassey, which took place in the historian’s childhood, in puranic terms (14). While other non-Western cinemas of the world like African and Chinese are able to deal with the past in similarly ‘puranic’ or mythological terms (15), the mainstream Hindi film appears strangely handicapped. My argument is that mainstream cinema’s address being directed entirely towards the post-colonial Nation with its modern self-image prevents it from using the puranas. The horror film, which is outside the mainstream and perhaps impervious to the modern nation, is not only able to rely on a puranic sense of the past but even suggests that modernity might benefit from puranic instruction.

Ashis Nandy, as a critic of rationality and enlightenment, has seen popular cinema as a response to the deadening homogenization and standardization wrought by the modernist imperative upon a variety of traditional cultures (16) but this is perhaps truer of the fantastic cinema outside the mainstream, notably the horror film, because the mainstream Hindi film, to all appearances, is still hostage to post-colonial modernity, as embodied in the Nation after 1947. In summary, to single out a characteristic of the two horror films just described, they convey the sense of post-colonial modernity being unable to bring individual histories together or, to phrase it in differently, sub-narratives resisting subsumption by the narrative of National history.

The Pakistani horror film

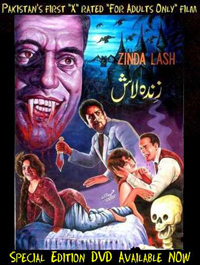

Unlike Indian cinema which has been well served by film theorists, very little theorizing has apparently done for cinema in Pakistan. This means that we will have to rely entirely on the evidence of the horror films to draw any conclusions. As in the previous section, I have chosen two Pakistani horror films – set forty years apart but not alike in their motifs. The first film Zinda Laash (Khwaja Sarfaraz, 1967) was the first film in Pakistan to be 'X' rated  and was almost banned. The film is actually a reworking of the story of Dr Jekyl and Mr Hyde with the difference that Mr Hyde is modeled on the figure of Dracula and is a blood-sucking vampire. In the film Dr. Tabani is experimenting on an elixir which, he believes, will grant him immortality. Matters, however, work out differently and he dies. When his assistant discovers this, she carries his corpse into a crypt in the basement but the scientist comes back to life and is now a vampire as, soon, is the assistant. The rest of the film follows the story of Bram Stoker’s Dracula quite closely. Dr Aqil, an associate of Dr Tabani, is the vampire's victim and looking for Aqil is his brother. Aquil had a fiancée named Shabnam and it is her that Tabani is lusting after. After she becomes a vampire who even abducts children her brother steps in. Dr Tabani is finally destroyed when the hero prays to God and an accident happens. He dislodges a screen from the window and the sunlight streaming into the room destroys the vampire. and was almost banned. The film is actually a reworking of the story of Dr Jekyl and Mr Hyde with the difference that Mr Hyde is modeled on the figure of Dracula and is a blood-sucking vampire. In the film Dr. Tabani is experimenting on an elixir which, he believes, will grant him immortality. Matters, however, work out differently and he dies. When his assistant discovers this, she carries his corpse into a crypt in the basement but the scientist comes back to life and is now a vampire as, soon, is the assistant. The rest of the film follows the story of Bram Stoker’s Dracula quite closely. Dr Aqil, an associate of Dr Tabani, is the vampire's victim and looking for Aqil is his brother. Aquil had a fiancée named Shabnam and it is her that Tabani is lusting after. After she becomes a vampire who even abducts children her brother steps in. Dr Tabani is finally destroyed when the hero prays to God and an accident happens. He dislodges a screen from the window and the sunlight streaming into the room destroys the vampire.

The first observation to be made about Zinda Laash is that, where the Indian examples cited in the last section and Bram Stoker’s novel are ‘fantastic’, the film may be defined as ‘uncanny’, i.e: rational explanations are provided at every step. The film begins with a dedication to God but declines to invoke the occult or even divinity – although it does leave itself open to religious interpretation ( 17). Faith, I propose, is sufficiently elastic to allow an Islamic artifact the same qualities as the Cross in the Dracula films. In an Indian vampire film Bandh Darwaza (Shyam and Tulsi Ramsay, 1990) the vampire is equally defenseless against the Cross, the Hindu Om and the Koran, as if to demonstrate its faith in secularism.

The accident letting the sunlight in at the conclusion of Zinda Laash can be attributed to the hero’s prayers but most films about religious belief have no difficulty in introducing God-induced miracles and the film’s disinclination here should be taken note of. The deliberate banality of the resolution chosen leads one to interpret the ending as agnostic and the film is perhaps suggesting that there are man-made things outside God’s purview. Of course, since the first cause in Zinda Laash is the failure of a scientific experiment, it might destroy the compositional unity of the film for religion to provide the eventual solution but the issue is this: why pick on science at all for the initial disturbance? The film faced censor trouble only for its suggestive dances but I would like to argue that just as Indian horror cinema chooses the occult for the initial disturbance as a way of resisting post-colonial modernity, Zinda Laash chooses science as a way of resisting the religious nation.

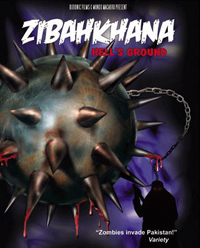

Where Zinda Lash is tentative in its horror, Omar Khan’s Zibahkhana (2007)  is almost ferocious. The film was a huge multiplex success in Rawalpindi and a private screening for students in Lahore virtually caused a riot but Benazir's assassination saw it being withdrawn (18). The film brings together the zombie film (The Night of the Living Dead, 1968) and the splatter film (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, 1974) and is, once again, ‘uncanny’ rather than ‘fantastic’. In this film a group of five college students who set out for a concert and take a short cut across unfamiliar terrain outside the city. When they stop in a patch of degraded forest close to a polluted stream, they run into a bunch of zombies – evidently created by the pollution – one of whom bites a member of the group in the leg, eventually leading to his becoming ‘infected’ as well. The other young people however escape but only to get deeper into the forest. When they meet a fakir offering to guide them, they admit him into the car until he starts attacking them. The fakir is finally caught under their car but his death is of little avail because they run into a dwelling deeper in the forest, a zibahkhana (slaughterhouse) with a burqa-clad cannibal on the loose and it turns out that they are providing human meat to the zombies the group encountered earlier. is almost ferocious. The film was a huge multiplex success in Rawalpindi and a private screening for students in Lahore virtually caused a riot but Benazir's assassination saw it being withdrawn (18). The film brings together the zombie film (The Night of the Living Dead, 1968) and the splatter film (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, 1974) and is, once again, ‘uncanny’ rather than ‘fantastic’. In this film a group of five college students who set out for a concert and take a short cut across unfamiliar terrain outside the city. When they stop in a patch of degraded forest close to a polluted stream, they run into a bunch of zombies – evidently created by the pollution – one of whom bites a member of the group in the leg, eventually leading to his becoming ‘infected’ as well. The other young people however escape but only to get deeper into the forest. When they meet a fakir offering to guide them, they admit him into the car until he starts attacking them. The fakir is finally caught under their car but his death is of little avail because they run into a dwelling deeper in the forest, a zibahkhana (slaughterhouse) with a burqa-clad cannibal on the loose and it turns out that they are providing human meat to the zombies the group encountered earlier.

While Zibahkhana also begins with a prayer to God, it cannot escape one’s notice that the film itself is far from religious. Apart from the film providing a first cause – industrial pollution – which is outside the purview of religion, apart from being a critique of the fetish of meat-eating (19), it uses images associated with religious instruction to evoke horror. Since the fakir is a religious person and the burqa is attire prescribed by Islam, having a burqa-clad killer/ cannibal may even be considered anti-religious (20). Where the Indian horror films and Zinda Lash offer resistance to the dominant ideologies of their respective nations, it is not unreasonable to argue that Zibahkhana goes further and is consciously adversarial.

Coming to the spectator profile of the Pakistani horror films, one gets a sense that it is vastly different from that of the Hindi horror film. Industry data is hard to come by but the Hindi horror film is more successful in single-screen dominated circuits rather than in the multiplexes (21). This suggests that it is not the upwardly mobile spectators of the metropolitan cities but more those in the smaller towns and in places where admissions are cheaper that are the audiences. The horror film may be addressing a class economically lower than those attuned to the mainstream film, perhaps a public (or an aspect of the public) less integrated with the ‘modern nation’. As regards the Pakistani films, no industry data is available but the insider portrayal of the college students in Zibahkana as modern and carefree corresponds to those portrayed in the Bollywood youth film – like Wake up Sid (2009), for instance, which was a multiplex success (22). It can be argued on the basis of this limited data that the Pakistani horror film addresses the same class within Pakistan that the mainstream Hindi film addresses within India the economically middle and upper echelons. This implies that while the dominant ideology of modernity within India is maintained by the upper-class elite, the elite has little or no control over the dominant ideology in Pakistan which is rigidly Islamic regardless of who is ruling the country politically.

The political factor of pertinence with regard to the creation of Pakistan is that while the Muslim community in India had a very small middle-class; apart from medical doctors, lawyers or clergy, everyone of ability apparently gravitated to high posts in the government or the army (23). This meant there was a large class gap between the leaders of the Muslim League and their followers. Jinnah was himself elegant and Westernized (24) and far from the devout Muslim that the future leader of a theocratic Islamic state would be, while the bulk of his following was different. Since Pakistan was created on religious grounds, it became Islamic although Jinnah himself might have wanted it to be secular. The elite class represented by the leaders of the Muslim League has continued to rule Pakistan and much of the class is educated abroad but, apparently, their following has gradually imposed its collective will on Pakistan’s leadership.

Conclusion

Film studies as a discipline usually discourages the expression of opinions about what cinema ‘should be’ but, having suggested that minority cinema can fulfill an adversarial political purpose, I should perhaps conclude in this way. This essay has been about the horror film, or rather, about cult horror and its resistance to the dominant ideology for which mainstream cinema is often a useful vehicle. The cult horror film creates unease around certain valorized notions or objects and goes far beyond merely creating disgust or revulsion. To recognize this, one need only look at the unease generated by a film like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which makes it seem that nothing will be forbidden to the spectator. Even if the overtly political reading given to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is disregarded as ‘implausible’, the disquiet it generates may still be understood as resistance to the covert ideological coercion inherent in popular entertainment. A mainstream horror film – like The Exorcist – does not perform the same role and actually reinforces the dominant ideology. Where The Texas Chainsaw Massacre locates its narrative in a marginal part of America, a corner hidden away from public attention, The Exorcist not only locates its action plum in the middle of mainstream America but may also be interpreted as a warning to Christian America that reinforces the dominant religious prejudices.

For reasons already explained, there is nothing in Indian cinema that corresponds to mainstream horror and the horror film is ‘B’ category cinema resisting the dominant ideology of the modern nation but hardly adversarial. At the same time, there has never been any kind of cult cinema in India to generate any ‘political’ disquiet. One reason may be that Indian film aesthetics, as has now been sufficiently demonstrated, is based not on cognition but on recognition and the fan knows what to expect. Thus, the Hindi film is a particular product of ‘the aesthetics of identity’ rather than the ‘aesthetics of opposition’ (25). A typical also trivial product of the latter is the detective story, which functions, as a rule, on the basis of the reader’s ignorance of ‘whodunit’. If familiarity is demanded, films will be hard-pressed to produce shock and disquiet – of the kind generated by cult horror. This perhaps explains the predictability of the Indian horror film. The Pakistani horror film is not very different – although Zibahkhana is much more adversarial. These films draw their plots from well known material like Dracula and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and the borrowing perhaps also owes to the need to reproduce the familiar.

Art cinema in India might also have been cult cinema and the ideal vehicle for producing disquiet but the fact that it depends entirely on State patronage has produced some unfortunate results. Art cinema in India is virtually fulfilling the cultural agenda of the State by dealing with subjects publicly regarded as important: human rights, communalism, agrarian issues etc. Selection for the Indian Panorama at the IFFI which showcases the films presenting an 'authentic' picture of India is crucial for art cinema. This means that a large number of these art films unwittingly serve the modern Indian State as cultural artifacts. If one were to regard the true function of film art as culturally adversarial, what Indian art cinema needs is the cult film and cult horror could be a rewarding influence.

Notes

| 1. |

Noël Carroll, Why Horror? From Mark Jancovich (Ed.), Horror: The Film Reader, London & New York, Routledge, 2002, p37. |

| 2. |

Frederic Jameson, Magical Narratives: Romance as Genre, New Literary History, 7, 1 (Autumn, 1975, pp133-63). |

| 3. |

Tania Modleski, The Terror of Pleasure: The Contemporary Horror Film and Postmodern Theory, Leo Braudy, Marshall Cohen (Eds.), Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, p 694. The term ‘ideological apparatus’ is derived from the writing of Louis Althusser. According to Althusser, ideological state apparatuses (e.g. religion, education, the family, media culture) function as indirect control structures because modern hegemony as not exercised by direct coercion but by achieving the consent of the dominated through the use of the media and institutions. Louis Althusser, Lenin and Philosophy and other Essays, (Trans.: Ben Brewster) New York: Monthly Review, 1971 |

| 4. |

Robin Wood, Introduction, from A Button, R Lippe, T Williams, R Wood (Eds.) American Nightmare: Essays on the Horror Film, Toronto: Festival of Festivals, 1979, pp 20-2. |

| 5. |

Joan Hawkins: Sleaze Mania, Euro-trash and High Art: The Place of European Art Films in American Low Culture, from Mark Jancovich (Ed.), Horror: The Film Reader, London & New York, Routledge, 2002, pp 125-134. |

| 6. |

Mike Featherstone, The Body in Consumer Culture, Theory, Culture and Society, September 1982, vol.1, No.2, pp18-33. |

| 7. |

A characteristic of the horror film is that – like art cinema – it caters to a cult following. See Robin Wood, Introduction, from A Britton, R Lippe, T Williams, R Wood (Eds.) The American Nightmare: Essays on the Horror Film, Toronto: Festival of Festivals, 1979, pp 7-28. |

| 8. |

Sunil Khilnani, The Idea of India, New Delhi: Penguin, 1998, p 61. |

| 9. |

Ashis Nandy, The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self Under Colonialism, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983. |

| 10. |

I mean devotion leading to a happy outcome because of divine intervention. An example would be the family dog empowered by divinity to assist in the resolution of misunderstandings as in HAHK. |

| 11. |

Tsvetan Todorov, The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre, (Trans. From French by Richard Howard), Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1975, pp24-40.

|

| 12. |

The regional cinemas – Telugu and Kannada specifically – are often rich in fantasy and mythological elements. It is perhaps significant that these two cinemas addressed constituencies largely in regions indirectly ruled by the British – Hyderabad and Mysore. They are apparently less ‘post-colonial’ than Hindi and Tamil cinemas.

|

| 13. |

See MK Raghavendra, Seduced by the Familiar: Narration and Meaning in Indian Popular Cinema, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008, pp31-40.

|

| 14. |

Partha Chatterjee, The Nation and its Fragments, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993, pp84-85.

|

| 15. |

For instance, the Chinese filmmaker Zhang Yimou has even attained international recognition though his mythological treatment of Chinese ‘history’, e.g Hero (2002). African filmmakers who have attained renown include Suleymane Cisse from Mali – Yeleen (1987).

|

| 16. |

Ashis Nandy, An Intelligent Critic’s Guide to Indian Cinema, Deep Focus Vol. I No.I, December 1987, p69.

|

| 17. |

|

| 18. |

Achal Prabhala, 31 Flavours of Death, issue #15 ‘Pulp’, Bidoun. www.bidoun.com.

|

| 19. |

|

| 20. |

Unlike the makers of Indian horror films who do not talk about their films as political, here is Omar Khan, the articulate director of Zibahkhana on the burqa, which apparently frightened him as a child: “(it is) a fantastically gothic and dramatic outfit that manages to strip all expression, emotion and warmth from a human face.” Achal Prabhala, 31 Flavours of Death, issue #15 ‘Pulp’, Bidoun. www.bidoun.com.

|

| 21. |

|

| 22. |

|

| 23. |

Percival Spear, A History of India, Vol.2. Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1970, p 223.

|

| 24. |

|

| 25. |

Lothar Lutze. From Bharata to Bombay: Change and Continuity in Hindi Film Aesthetics, from (Eds.) Beatrix Pfleiderer and Lothar Lutze, The Hindi Film: Agent and Re-agent of Cultural Change, Delhi: Manohar Publications, 1985, p5.

|

M K Raghavendra is the founder-editor of Phalanx

Courtesy: horrornews.net

Courtesy: best-horror-movies.com

Courtesy: cinemata.files.wordpress.com

Courtesy: 2.bp.blogspot.com

Courtesy: bollywoodworld.com

Courtesy: thehotspotonline.com

Courtesy: t2.gstatic.com

|

|

|

|

|

|

Top |

|

|

|

|

|